![]() Criticism

Criticism

![]() Criticism

Criticism

German street credibility

Daniel Richter’s figurative exploration of urban vistas and housing projects resonates powerfully

by David Gordon Duke

Pink Flag — White Horse

Paintings by Daniel Richter

Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, UBC, until Nov. 28

“Beauty by confusion, truth by collision.” That’s the slogan of German painter Daniel Richter, who makes much of his art from the familiar images of our own moment. A small sample of his current work, incorporating seedy street scenes, vistas of urban housing projects, and skins in camouflage fatigues, is on display at UBC’s Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery.

“Beauty by confusion, truth by collision.” That’s the slogan of German painter Daniel Richter, who makes much of his art from the familiar images of our own moment. A small sample of his current work, incorporating seedy street scenes, vistas of urban housing projects, and skins in camouflage fatigues, is on display at UBC’s Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery.

Richter is recognized as one of the most significant German artists to emerge in the last few decades. Recently he has turned to a re-definition of figurative painting, with intriguing narrative sub-texts. He’s also caused something of a stir in the reviving art market. London’s Daily Telegram reported that in a recent auction a Richter canvas was knocked down for over a quarter of a million dollars. Richter has just had an important New York show at the David Zwirner Gallery. This exhibit, co-organized by Toronto’s Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery at Harbourfront, is his first Canadian exposure.

Now in his early forties, Richter is at first glance an unlikely player in the dubious world of high-finance art. He grew up in the punk/street culture of his adopted Berlin, and only began formal art training in Hamburg in his early thirties. His Canadian curators make an exaggerated claim that Richter "has re-invented representational painting, thought to have been made obsolete by photography." (This may simply be artspeak for, “We were taught to regard representational art as ideologically suspect, but wow, this guy is on to something.”) In fact the UBC show is a fascinating view of how undeniably contemporary images can resonate with complex, even contradictory high art traditions.

The Belkin is first and always a university gallery. There’s none of the razzle dazzle of a big art museum, none of the commercialism of a private gallery. It’s not an inviting experience for many visitors, nor does it particularly need to be: the academic milieu assumes viewers know why they're there and can forge their own relationship with the work. This show offers rather flimsy assistance for non-specialist viewers. A handout proffers the shortest of biographies, a map of the dozen pieces on display giving Richter’s difficult titles, details of provenance and media, and nothing more (though a good, if expensive, catalogue and a more arcane zine are available for purchase).

Under the circumstances this is the best strategy. Richter’s titles — a few in English, the rest in German — are aggressively cryptic. Puns and wordplay abound; translations can't possibly tie down the connotations. And the images themselves are rich in allusion. The zine contains the text “The more you know about the historical or ecological background of images, the more you can interpret,” around which Richter has scribbled “But it’s not necessarily the truth about it.” His canvases work on any number of levels, with more than enough attitude to make an impact with or without any interpretive apparatus.

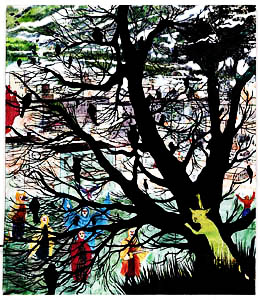

Two-thirds of the canvases are large, though the show’s title derives from one of four small oils. Das Mißverstandnis (Misunderstanding), the large canvas used as the Belkin show’s on-line image, may not be the most characteristic of the Richter works, but it nonetheless stops viewers dead in their tracks. It’s a rich, complicated composition. The background consists of a drab expanse of apartments and banal buildings, in the middle ground, a small group of figures dressed in brightly coloured bird costumes; the foreground is the latticework of a leafless tree with crows, with a guiltily observed, almost cartoon-like cat: is it after the crows, after the costumed figures, or what? The strong black lines of the winter tree and brilliant colours of the costumes suggest both stained glass and woodcuts; the tree triggers memories of 19th-century painter Caspar Friedrich David’s The Tree of Crows; the vista evokes Pieter Bruegel’s Hunters in the Snow.

What does it add up to? It’s both perplexing and moving — complex and academic on the one hand, and as visceral as a rock concert on the other. Richter’s sensibility fuses the now of street people, housing projects, raves, and drug busts with the 19th- century German Romantic tradition of landscapes and loners. Though his work is unmistakably connected to explicitly German traditions, we recognize its immediacy — images of this time, of our exact moment.

Not all Richter’s international critics know precisely what to make of his new engagement with the past. In the zine, Robert Linsley maintains that “How Richter will develop is unforeseeable....[His] work speaks to the darkening present. Paradoxically it does this through the way that it asserts the relevance and value of the artistic culture of a hundred years ago.” His Vancouver audience may have their own problems with his work. But few will leave the gallery unaffected by his disquieting vision.

Vancouver Sun

13 Nov. 2004

archives

archives