Wilhelm von Gloedens Arcady

Remarks on an obsessed career

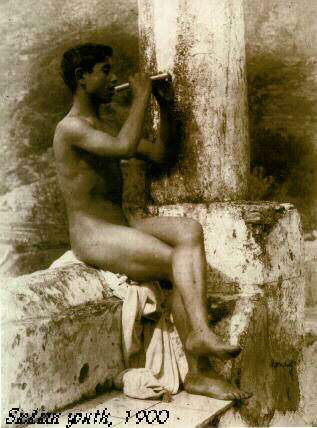

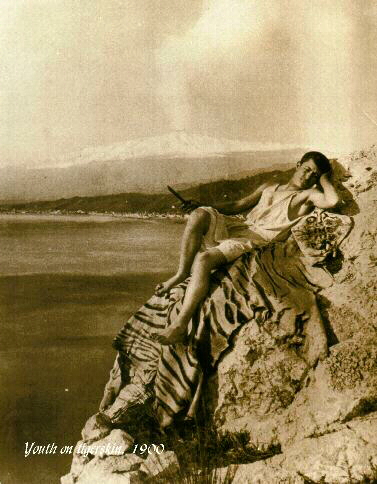

Today, anyone who visits the Sicilian tourist

resort of Taormina and picks through the stands of the

"cartolerias", the local postcard merchants and

souvenir traders - for instance stopping by the venerable firm of

the Malambri Brothers - may come across some sepia-toned

postcards depicting Mount Etna rising in the background and

youths posed along terraces or leafy galleries. Occasionally the

boys are wearing Greek togas; more frequently, however, they

appear in God's or (more in keeping with the setting) the gods'

splendour. Turning the cards over, one discovers the name of the

photographer, "Wilhelm von Gloeden".

Who was the man who left such an enduring mark on Taormina, the man who bequeathed his prodigious photographic estate to Pancrazio Bucini (his last model who only passed away in 1977 at the age of eighty-seven), the man who made his entry into the history of photography as the master of the male nude?

Wilhelm von Gloeden is a legendary figure, and there are ample grounds for the legends that have sprung up around his name. The life of this Prussian baron, who was born in 1856 in East Prussia and who died in Taormina in 1931, reads like a fairytale dating from the late Victorian or Edwardian periods. Von Gloeden, a young Prussian country squire, left his homeland for Italy to regain his physical (he suffered from a disabling lung condition) and mental health (the psychological distress he experienced as a pederast unable to indulge his erotic fantasies). After arriving in Taormina, which at the close of the nineteenth century was a small, impoverished Sicilian town unknown to tourists, not only did health and psyche improve, but von Gloeden was able to embark upon his artistic career.

Wilhelm von Pluschow, a distant relative living in Naples, inspired von Gloeden to dedicate himself to the craft of his newly discovered photographic hobby. Using local boys as models, von Gloeden endeavoured in his "tableaux vivants" to achieve a vision of Arcady. The story of the baron's life became the subject of a biography by Roger Peyrefitte, the French sensationalist author. The acceptance of Wilhelm von Gloeden's libertine photography during the prudish Victorian era, an age when, apart from medical or ethnological depictions, any graphic rendering of the sexual organs was censured, is a phenomenon which invites investigation.

According to Charles Leslie, one of von Gloeden's

earliest serious biographers, the baron was "one of those

rare men of the nineteenth century who refused to bargain away

his innernature, consent to its annihilation, in order that he

might be allowed to assume his place in the so-called civilised

Western world, one which officially condemned him for what he

was." By Leslie's account von Gloeden was a man who treated

everything as subordinate to the vital task of self-realisation.

For this author, influenced by the stonewall movement and the

general awakening of consciousness among homosexuals during our

century's seventies, von Gloeden symbolised the act of

liberation, posed a paradigm example of the artist and his

self-realisation. Von Gloeden, however, is an important figure

for two further reasons: his place in the history of photography,

and his contribution to the local heritage of Taormina, his

adopted home. Especially at the beginning of his residency, while

he was still a man of independent means, von Gloeden was a

generous community benefactor, helping the small Sicilian town to

eventually become one of the fin de si?cle's most

prestigious watering holes. By the turn of the century, poets and

actors, painters and famous society figures flocked to Taormina,

making it a must on their grand Italian tours. After touring the

city's charming Ancient Greek theatre, the travellers would pay a

visit to von Gloeden at his studio, purchasing his pagan

"Illustrations of Theocritus and Homer" - as von

Gloeden called his photographs - images which were mounted in

travel albums alongside the architectural studies of Fratelli

Alinari of Florence, and the Neapolitan folk portraits of Giorgio

Sommer, a Frankfurt-born photographer living and working in

Naples. Von Gloeden's visitors' book, since lost, could boast the

signatures of Oscar Wilde, Gabriele d'Annunzio, Eleonora Duse,

the King of Siam and King Edward VII, as well as those of such

well-known bankers and industrialists as Morgan, St?nnes, Krupp,

Vanderbilt and Rothschild. In 1911, von Gloeden was awarded a

medal in recognition of his valuable assistance in helping

Taormina become a favourite tourist destination.

According to Charles Leslie, one of von Gloeden's

earliest serious biographers, the baron was "one of those

rare men of the nineteenth century who refused to bargain away

his innernature, consent to its annihilation, in order that he

might be allowed to assume his place in the so-called civilised

Western world, one which officially condemned him for what he

was." By Leslie's account von Gloeden was a man who treated

everything as subordinate to the vital task of self-realisation.

For this author, influenced by the stonewall movement and the

general awakening of consciousness among homosexuals during our

century's seventies, von Gloeden symbolised the act of

liberation, posed a paradigm example of the artist and his

self-realisation. Von Gloeden, however, is an important figure

for two further reasons: his place in the history of photography,

and his contribution to the local heritage of Taormina, his

adopted home. Especially at the beginning of his residency, while

he was still a man of independent means, von Gloeden was a

generous community benefactor, helping the small Sicilian town to

eventually become one of the fin de si?cle's most

prestigious watering holes. By the turn of the century, poets and

actors, painters and famous society figures flocked to Taormina,

making it a must on their grand Italian tours. After touring the

city's charming Ancient Greek theatre, the travellers would pay a

visit to von Gloeden at his studio, purchasing his pagan

"Illustrations of Theocritus and Homer" - as von

Gloeden called his photographs - images which were mounted in

travel albums alongside the architectural studies of Fratelli

Alinari of Florence, and the Neapolitan folk portraits of Giorgio

Sommer, a Frankfurt-born photographer living and working in

Naples. Von Gloeden's visitors' book, since lost, could boast the

signatures of Oscar Wilde, Gabriele d'Annunzio, Eleonora Duse,

the King of Siam and King Edward VII, as well as those of such

well-known bankers and industrialists as Morgan, St?nnes, Krupp,

Vanderbilt and Rothschild. In 1911, von Gloeden was awarded a

medal in recognition of his valuable assistance in helping

Taormina become a favourite tourist destination.

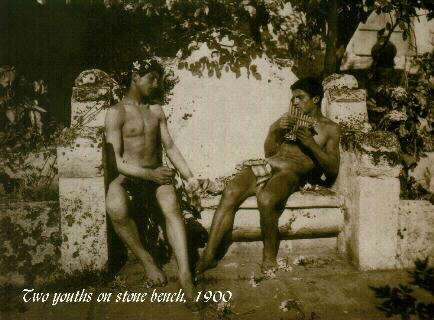

In his work, von Gloeden presented a vision of

Taormina's past as a golden age brimming with Greek, Roman, Arab

and  Norman

influences. Like the island of Capri, Taormina became a favourite

haunt of affluent homosexual society. Such customers for von

Gloeden's albumen prints were astonished by their realism a

quality which suffered when - as in the paintings of Hans von

Mar?es - any attempt was made at idealisation. They were apprised

of the photographs' erotic possibilities, whereas educated

mainstream tourists were referred to the sexually neutral

Arcadian costumes and implements.

Norman

influences. Like the island of Capri, Taormina became a favourite

haunt of affluent homosexual society. Such customers for von

Gloeden's albumen prints were astonished by their realism a

quality which suffered when - as in the paintings of Hans von

Mar?es - any attempt was made at idealisation. They were apprised

of the photographs' erotic possibilities, whereas educated

mainstream tourists were referred to the sexually neutral

Arcadian costumes and implements.

What makes von Gloeden's work so fascinating to us today was his ambition to substitute his own personal cosmos for the realities of his age, a design he carried out to the point of insinuating himself, wearing costume apparel, into the midst of his oeuvre. Taormina furnished him with the possibility of constructing a playful, aesthetic counter-world, one which he (and here lies the work's authenticity) never dismissed as solely an artistic fantasy. What was important for him was the aesthetic integrity of his transformations. If one compares his oeuvre with the work of his contemporaries von Pluschow and Vincenzo Galdi, it becomes apparent that von Gloeden not only developed his own narrative style, but also cultivated a different working relationship with his models. Occasionally, photographs of von Pluschow have been attributed to von Gloeden, a confusion that arises because von Pluschow apparently sold von Gloeden's work. Another ground for muddled accreditations has been documented in collections published by such authors as Jean Claude Lemagny and Jack Woody: from time to time, the fragile albumen coating had so deteriorated that the originator's mark had become effaced. In such cases it is impossible to accredit the images authoritatively. However, those nude studies in which the secondary sexual traits have been accentuated stem in all likelihood from Galdi, a photographer with an inclination towards pornographic scenes.

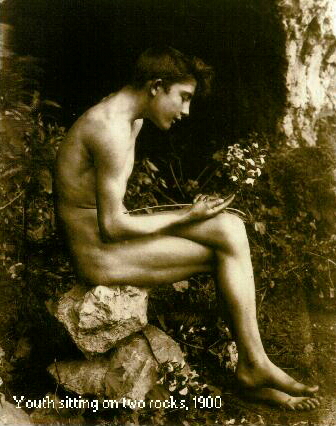

Photography

offered von Gloeden the possibility of transforming his

surroundings by applying the Pygmalion effect in reverse. He

endeavoured to blend the antique and modem worlds, sought to

create a timeless theatre of desirous fantasy. This amalgamation

is clearly evident in one particular study of a youth who had

regularly modelled for von Gloeden over a period of years: in

complementary pose he shares the frame with a popular Greek

statue. Ulrich Pohlmann, who has written the best von Gloeden

monograph published to date, traces von Gloeden's development

from amateur to professional photographer with reference to the

progression of his "living pictures". Pohlmann often

deduces the chronology of von Gloeden's images by light of the

artist's evolving iconography. The baron's living pictures were

carefully composed photographic re-creations of actual scenes.

During the last quarter of the nineteenth century it was quite

common to photograph re-enactments of historic events, or compose

portraits of folkloric customs and trades. Von Gloeden, too,

worked in this photographic genre, producing a lengthy series of

pictorial studies of fishermen and couples dressed in traditional

attire. Also, while touring through Tunisia, he photographed its

inhabitants dressed in native garb, and exposed a number of

plates investigating their physiognomies. But quite aside from

his topographic views of Taormina, or his documentary photographs

- for instance his scenes of Messina in the wake of an earthquake

- von Gloeden's fountainhead theme was his living portraits, his

photographs of the boys of Taormina, youths whom he considered to

be the "representatives of an archaic, classless

society".

Photography

offered von Gloeden the possibility of transforming his

surroundings by applying the Pygmalion effect in reverse. He

endeavoured to blend the antique and modem worlds, sought to

create a timeless theatre of desirous fantasy. This amalgamation

is clearly evident in one particular study of a youth who had

regularly modelled for von Gloeden over a period of years: in

complementary pose he shares the frame with a popular Greek

statue. Ulrich Pohlmann, who has written the best von Gloeden

monograph published to date, traces von Gloeden's development

from amateur to professional photographer with reference to the

progression of his "living pictures". Pohlmann often

deduces the chronology of von Gloeden's images by light of the

artist's evolving iconography. The baron's living pictures were

carefully composed photographic re-creations of actual scenes.

During the last quarter of the nineteenth century it was quite

common to photograph re-enactments of historic events, or compose

portraits of folkloric customs and trades. Von Gloeden, too,

worked in this photographic genre, producing a lengthy series of

pictorial studies of fishermen and couples dressed in traditional

attire. Also, while touring through Tunisia, he photographed its

inhabitants dressed in native garb, and exposed a number of

plates investigating their physiognomies. But quite aside from

his topographic views of Taormina, or his documentary photographs

- for instance his scenes of Messina in the wake of an earthquake

- von Gloeden's fountainhead theme was his living portraits, his

photographs of the boys of Taormina, youths whom he considered to

be the "representatives of an archaic, classless

society".

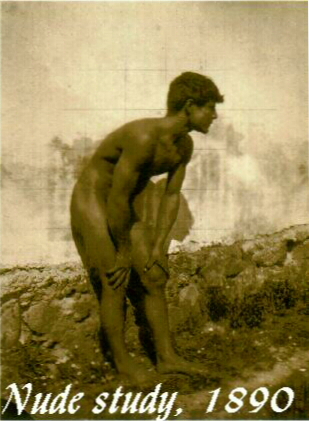

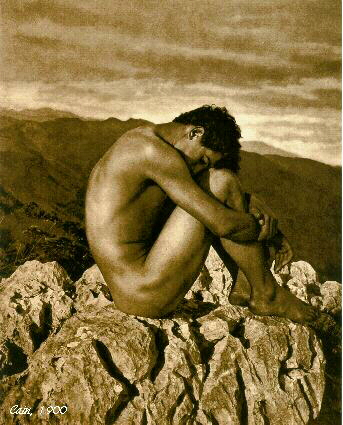

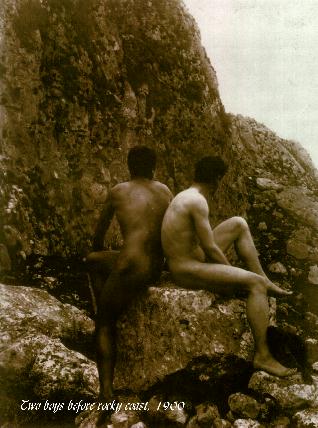

Wilhelm von Gloeden is important to the history

of photography as an innovator of the nude image - principally of

the male nude. Von Gloeden was a

pioneer, one of the first to compose his nude studies outside the

studio. Nineteenth century conventions demanded that a fig leaf

be placed over the genitals, or that the retoucher's dark-room

art strategically blur the anatomy. Von Gloeden dispensed with

such strictures, his large format plate camera faithfully

reproducing each and every detail of the physique. The baron was

chiefly a pure photographer, his point-of-view blunt and

straightforward. Although he occasionally attempted to idealise

cosmetically the physiques of his models, they always remained

peasant youths. Von Gloeden's portrait settings were balustrades

with splendid views, or, festooned with antique amphorae, its

walls ornamented with an intricate palm design, the inner

courtyard of his own residence. The wildly romantic outlying

mountains also provided choice photographic settings. Together

with his models, von Gloeden would venture to lonesome sites

where he could unhurriedly compose his photographs, many of which

called for protracted shutter exposures.

nude. Von Gloeden was a

pioneer, one of the first to compose his nude studies outside the

studio. Nineteenth century conventions demanded that a fig leaf

be placed over the genitals, or that the retoucher's dark-room

art strategically blur the anatomy. Von Gloeden dispensed with

such strictures, his large format plate camera faithfully

reproducing each and every detail of the physique. The baron was

chiefly a pure photographer, his point-of-view blunt and

straightforward. Although he occasionally attempted to idealise

cosmetically the physiques of his models, they always remained

peasant youths. Von Gloeden's portrait settings were balustrades

with splendid views, or, festooned with antique amphorae, its

walls ornamented with an intricate palm design, the inner

courtyard of his own residence. The wildly romantic outlying

mountains also provided choice photographic settings. Together

with his models, von Gloeden would venture to lonesome sites

where he could unhurriedly compose his photographs, many of which

called for protracted shutter exposures.

At the close of the nineteenth century, von Gloeden's work found swift recognition within the world of photography, his images appearing at important international exhibitions. During 1893 his photographs were published in such trend-setting periodicals as "The Studio" and Velhagen & Klasing's "Kunst f?r Alle" (Art for everyone). In 1898 von Gloeden became a corresponding member of Berlin's "Freie Photographische Vereinigung" (Free Photographic Society).

Von Gloeden's oeuvre, which chiefly took shape between 1890 and 1914, not only intimated his personal homoerotic wishes and projections, but also manifested some typical tendencies of the era, tendencies shared by his artist contemporaries. The return to a virgin setting, the romanticising of the pastoral life - von Gloeden considered the local peasants to be of "noble simplicity and quiet magnitude" - expressed the era's general disaffection with civilised life and a yearning for the bucolic past. Uncensored nude photography was one gesture of the struggle against the nineteenth century dogmatism which vilified the body.

Two factors appear astonishing to us today: how was

it possible that Victorian censors allowed the publication of

nude images so unrepentantly realistic and how did von Gloeden

succeed in convincing local boys to pose for him without either

their families or the Church intervening? Von Gloeden's

photographs are, as we have already noted, neither extravagantly

provocative nor blatantly pornographic - in point of fact, they

quite usually exclude an aura of innocence.

Two factors appear astonishing to us today: how was

it possible that Victorian censors allowed the publication of

nude images so unrepentantly realistic and how did von Gloeden

succeed in convincing local boys to pose for him without either

their families or the Church intervening? Von Gloeden's

photographs are, as we have already noted, neither extravagantly

provocative nor blatantly pornographic - in point of fact, they

quite usually exclude an aura of innocence.

"Although the erotic inspiration and sometimes even the erotic content of these photographs is self-evident", remarks Gert Schiff, "the Victorian public and censors, in a consummate act of self-deception, succeeded in viewing these images as ethnological studies or lyrical evocations of antiquity". Von Gloeden's importance to the history of nude photography arises from his utter dismissal of the genre's taboo, the confident manner in which he manipulates his ephebic, androgynous models, and the sheer magnitude of his output. With the exception of the platinum prints of the Boston philanthropist Fred Holland Day, a contemporary of von Gloeden's who filled his ouvre with analogous motifs (likewise legitimating the nudity of his young models as an exigency of pagan theme), von Gloeden has no peer with respect to both quantitative and qualitative achievement until the arrival of Robert Mapplethorpe during the seventies and eighties of our century.

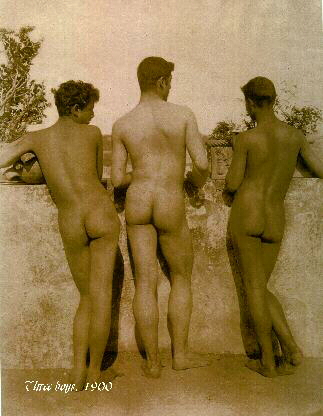

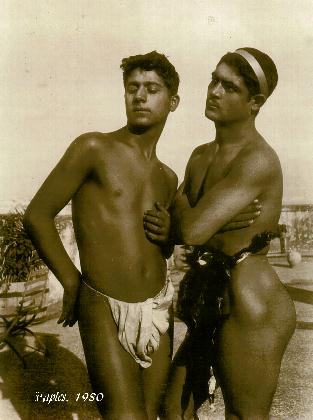

Gratuitous sexual and pornographic images are

absent from von Gloeden's work. The strong formal elements of his

images remain faithful to the classical rules of composition

which prevailed during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries;

so too,  his preference for

the androgynous male nude. Fully evident is a homosexual

preoccupation with such libidinally charged areas of the anatomy

as the penis and buttocks; among nineteenth century work evincing

homosexual contents von Gloeden's images stand quite alone. He

predominantly works with two models, their body language

demonstrative of affection, devotion, Greek attachment. Yet

beyond this category there are also a number of portraits of

individuals in which the sexual connotations, though coded, are

far more blatant.

his preference for

the androgynous male nude. Fully evident is a homosexual

preoccupation with such libidinally charged areas of the anatomy

as the penis and buttocks; among nineteenth century work evincing

homosexual contents von Gloeden's images stand quite alone. He

predominantly works with two models, their body language

demonstrative of affection, devotion, Greek attachment. Yet

beyond this category there are also a number of portraits of

individuals in which the sexual connotations, though coded, are

far more blatant.

How did von Gloeden persuade the local boys to pose for him? Aside from the fact that their activity was remunerated, one must bear in mind that von Gloeden, a man of charisma, arrived in the community as a generous benefactor. In its "indigenous souls" he believed himself to have discovered the direct descendants of the ancient Greeks, a lineage which, though reduced to rags, retained its nobility. One must also bear in mind that, throughout the Christian Mediterranean, homosexuality was tacitly tolerated as a passing phase in a young man's life. "This could quite well be a result", Gert Schiff points out, "of the age-old Graeco-Roman tradition. But perhaps a more logical solution lies in the regional custom of keeping the two sexes separated until marriage, and thus in the wisdom of the church - to be magnanimous in all peripheral questions, yet utterly implacable with regard to the preservation of its own political power."

In one category of images, von Gloeden works with groups of youths whom he positions across the scene in various attitudes, some appearing at leisure, some kneeling, others standing or lying down. Such photographs not only evince an overall mood of hannony, but were also used as "acad?mies", or figure studies by artists. The youths in such photos appear unrelated to one another, disconnected. Other photographs used as figure studies feature models of various ages, their bodies established in ambiguous relationships. Such photos regularly provide disparate anatomical perspectives (for instance, frontal and rear) of two models standing in opposition.

Fauns, figures of

Pan, shepherds and Greek ephebic figures were perfect roles for

the boys of Taormina, these Southern European adolescents who, at

the century's turn, endowed with such healthy exhibitionistic

qualities, took great narcissistic pleasure in their physiques.

Many were natural actors, a trait which helped them through the

lengthy photo sessions. Gloeden was a contemporary of

historicism. In his work, he insouciantly mixed prop accessories

associated with a wide variety of historical epochs. For the

French philosopher Roland Barthes, this clash of historical

vernaculars was a disturbing stylistic flaw. The boys are not

endowed with classically proportioned physiques; rather, their

bodies reveal their situations as hardworking peasant youths. But

today, this is exactly the artistic quirk which we find so

compelling: the idealised imagery of an historic paganism is

winnowed from these images by puberty's fey realism - each youth

has his own face, his own penis. The awkwardness of these

adolescent models posing upon their turn-of-the-century stage is

what appeals to the modern viewer's imagination and purges these

images of any pornographic content. Roland Barthes is quite

correct in observing that von Gloeden has taken "the antique

codex, hyperbolized it, applied it in inspissate layer (ephebi,

shepherds, ivy, palm branches, olive trees, grape vines, togas,

columns, stone slabs), but, (the first distortion) he

mixes the antique symbols, lumps together the Greek vegetation

cult, Roman figurine sculptures, and the 'classical nude' which

stems from the Ecole des Beaux Arts."'

Fauns, figures of

Pan, shepherds and Greek ephebic figures were perfect roles for

the boys of Taormina, these Southern European adolescents who, at

the century's turn, endowed with such healthy exhibitionistic

qualities, took great narcissistic pleasure in their physiques.

Many were natural actors, a trait which helped them through the

lengthy photo sessions. Gloeden was a contemporary of

historicism. In his work, he insouciantly mixed prop accessories

associated with a wide variety of historical epochs. For the

French philosopher Roland Barthes, this clash of historical

vernaculars was a disturbing stylistic flaw. The boys are not

endowed with classically proportioned physiques; rather, their

bodies reveal their situations as hardworking peasant youths. But

today, this is exactly the artistic quirk which we find so

compelling: the idealised imagery of an historic paganism is

winnowed from these images by puberty's fey realism - each youth

has his own face, his own penis. The awkwardness of these

adolescent models posing upon their turn-of-the-century stage is

what appeals to the modern viewer's imagination and purges these

images of any pornographic content. Roland Barthes is quite

correct in observing that von Gloeden has taken "the antique

codex, hyperbolized it, applied it in inspissate layer (ephebi,

shepherds, ivy, palm branches, olive trees, grape vines, togas,

columns, stone slabs), but, (the first distortion) he

mixes the antique symbols, lumps together the Greek vegetation

cult, Roman figurine sculptures, and the 'classical nude' which

stems from the Ecole des Beaux Arts."'

The boys knew no shame. At times with

enthusiasm, at other times, worn out by the long sessions, with

weary boredom,  they attempted to

follow the demands of their director - although they often

possessed no real insight into his purposes. However, another

portrait category exists in which the boys articulate no

artificial sentiment, but instead exclude the expectancy or

dreaminess peculiar to adolescence. These portraits, the most

genuine, are also the most successful.

they attempted to

follow the demands of their director - although they often

possessed no real insight into his purposes. However, another

portrait category exists in which the boys articulate no

artificial sentiment, but instead exclude the expectancy or

dreaminess peculiar to adolescence. These portraits, the most

genuine, are also the most successful.

Nude photography during the nineteenth century possessed two pre-eminent purposes: firstly, figure studies aided artists in the absence of live models; and secondly, sold surreptitiously, such images provided a pornographic stimulus. Von Gloeden's work did not always gain large audiences or find its way to exhibitions. Only select motifs were eligible to appear in Velhagen's periodical "Kunst f?r Alle", or were published alongside articles taking Sicily as their theme. Some photographs were accepted by periodicals which began to appear at the turn of the century, catering to the aesthetic tastes and psychological self-image of a male homosexual readership. Such periodicals, sold solely by subscription, naturally eluded a more general audience.

In 1893 "Kunst f?r Alle" published one of von Gloeden's photographs together with a caption remarking that the image depicted "naked natives of the Island of Sicily". The caption's ethnological flavouring was meant to excuse the image's overt nudity.

Von Gloeden's iconography of poses and settings emerges from the venerable classicist tradition. The most famous of such examples is Cain, von Gloeden's version of the painting Solitude by Hyppolyte Flaudrin. We know that many of von Gloeden's contemporaries collected his photographs. Works by such artists as Frederic Leighton, Alma Tademas and Maxfield Parish evidence their acquaintance with Gloeden's oeuvre. One particularly handsome example can be found in the study collection of Berlin's Hochschule der Kunste. Here, the pencilled grid applied to von Gloeden's albumen print is used to give impulse to other artistic projects. Von Gloeden remains an influence in contemporary art. Joseph Beuys, intrigued by the utopian themes, added his own designs to the baron's motifs. Also, artists ranging from Andy Warhol to Michael Buthe have used von Gloeden's erotically inspiring photographs in their work, creating their own interpretations.

Deprived of his family income, von Gloeden, the

aristocratic amateur, was obliged to employ his artistic hobby as

a means of livelihood. His photographs, exactly like those

of his distant relative, Wilhelm von Pluschow (who besides

merchandising his own "tableaux vivants", also

worked in Naples as a portrait photographer), could be ordered

from a catalogue of small proofs. Here, among images ranging from

genre studies to views of Taormina, from boys clad scantily to

not at all, von Gloeden's wide thematic range becomes apparent.

Interested parties could order their favourite scenes by number.

Von Gloeden's vivid photographic studies intimated to Europe's

homosexuals the fulfilment of their innermost fantasies. The

excessive strictures of the Wilhelmine epoch were circumvented;

through photos these men could find refuge and satisfaction in

the Arcady of the imagination.

Deprived of his family income, von Gloeden, the

aristocratic amateur, was obliged to employ his artistic hobby as

a means of livelihood. His photographs, exactly like those

of his distant relative, Wilhelm von Pluschow (who besides

merchandising his own "tableaux vivants", also

worked in Naples as a portrait photographer), could be ordered

from a catalogue of small proofs. Here, among images ranging from

genre studies to views of Taormina, from boys clad scantily to

not at all, von Gloeden's wide thematic range becomes apparent.

Interested parties could order their favourite scenes by number.

Von Gloeden's vivid photographic studies intimated to Europe's

homosexuals the fulfilment of their innermost fantasies. The

excessive strictures of the Wilhelmine epoch were circumvented;

through photos these men could find refuge and satisfaction in

the Arcady of the imagination.

The photographs are difficult to date with any certainty. Not until 1897 - a relatively late point in his career - did von Gloeden set about placing his work, in order and stamping the back of the majority of his prints. Unfortunately, his numbering fails to correspond with any chronology. Perhaps the best chronological clues are those provided by the boys von Gloeden worked with over a period of years. In such photographs we can follow the slow passage of adolescence. By and large, once a model had crossed the threshold from adolescence into young adulthood, he was no longer willing to pose for von Gloeden.

Publications springing up around von Gloeden's name have regularly brought to light new material, testifying to the wealth of his erotic motifs. The Italian journalist Pietro Nicolosi estimates von Gloeden's vast oeuvre to have at one point numbered some 7000 glass negatives, a figure by no means inflated.