Menu Main Page |

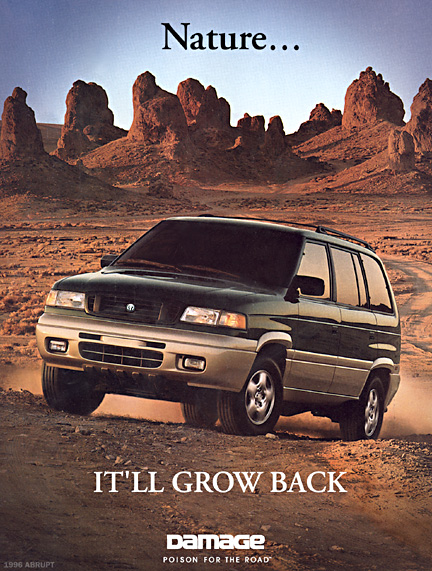

Ever since childhood, I have been intrigued by the world of advertising. I hummed jingles from popular commercials, and when reading magazines I often paid more attention to the ads than the articles. So when it came time to begin thinking about a career, it seemed clear that advertising was the field to which I was best suited. For me, as for most people in the American culture, advertising has always been a reality, something that exists unquestioned. But is that the way it should be? Is it right for a corporation to knowingly lure people, particularly teenagers, to cause such harm to their bodies? Like most people, I knew the facts about smoking. I had seen reports that proved tobacco manufacturers had known for the past thirty years that nicotine is addictive (Kent 1). I had read articles claiming that tobacco is responsible for thirty percent of all cancer deaths in the US and ninety percent of lung cancer deaths in men (Rapp 1). Given that all that was true, and that many consumers had seen the fatal effects of smoking first hand, what reason could they possibly have for smoking? Then it suddenly dawned on me: Despite the negative information about cigarettes that students had heard from health teachers and seen through the deaths of other smokers, the tobacco companies had still managed to present a positive image of themselves through advertising. The more I looked, the more evidence I saw of media saturation by tobacco companies. One afternoon, I observed over a dozen smokers who appeared to be well below the legal age of 18. In addition to this, two teens (whose ages I would estimate at 15) wore t-shirts featuring logos of popular cigarette brands. Kids were being put at risk because of advertising campaigns aimed at teens. Every day, more than 3000 US teenagers become regular smokers (Rapp 1). Although cigarette companies often claim not to target teens, studies have proven that "perceptions of cigarette brand advertising actually is higher among young smokers and that changes in market share resulting from advertising occur mainly in this segment" (Rapp 2). As Dr. Eriksen states, "There's only one loser in not selling tobacco to kids: the tobacco industry" (Hearn 4). And since 85 to 90 percent of smokers start before age 18, the losses would be great if tobacco companies ever stopped targeting teens (Samorodin 1). The Journal of the American Medical Association warns that "with straight faces [tobacco companies] will likely express shock that children respond to this campaign by taking up smoking... the success of the tobacco industry is dependent on recruiting people who don't believe that smoking kills... enticing children, Third World populations, and disadvantaged members of our society to smoke is the only way for tobacco companies to make up for numbers of smokers who quit or die" (Rapp 2). And kids are not the only ones at risk, advertisers have some very covert ways of attracting customers of all ages. Every year, tobacco companies spend $6 billion in marketing alone (Samorodin 1). Not all of this is spent in straight forward advertising campaigns. Some ways that advertising attempts to confuse the consumer are through cross-marketing (the joint promotion of a product and a movie) and infomercials (when advertisements are made to resemble television programs) (Davidson 1-2). Other methods used by advertisers include product placement (when products are inserted into movies, giving the impression that the actors prefer them) and guerilla marketing (when people are paid to spread rumors about a product) (Leonard 1). These types of campaigns create an environment where "it is difficult to tell the difference between art, advertisement, and product" (Neidsviecki 1). This type of advertising is clearly unethical. It attempts to trick the consumer into buying a product against their will, rather than convincing the consumer of the genuine merits of a product. Suddenly, I had to question my decision to pursue advertising as a career. It seemed a bit foolhardy to assume that a moral quandary would never arise in regard to an unethical ad campaign. But what would I do if faced with that type of problem? There was always the option of just walking away from the campaign, but in that scenario someone else would surely take my place and continue with the same practices I had objected to. Just walking away from the problem wouldn't be enough. There had to be more I could do. I mulled over the problem as I idly scanned the internet one afternoon. I hopped from search engine to search engine, typing in the words that I hoped might help me find an answer, or at least a direction. Somehow, in my blundering I found exactly what I was looking for. It was a page about Culture Jamming. Culture Jamming, according to jammer Mike Dey, is "an attempt to "jam" the transmissions of our corporate-controlled, media-consumer-industrial complex" (Mizrach 1). Jammers operate by inserting subversive meanings into newscasts, ads, and other media (Dery 1). Some examples of jamming include the following picture:  In highlighting negative aspects of a product, culture jamming helps to draw attention to the tactics advertisers use. For instance, in the example of the sport utility vehicle ad, a jammer questions the company's marketing strategy by ignoring the merits of the vehicle and instead focusing on the path of environmental destruction left in its wake. The principles of culture jamming are perhaps best exemplified in a quote from the Detritus Manifesto, a website committed to anti-consumerist thought: Our society spends a lot of time telling us that there is some brand new, fresh cultural produce, generated from thin air and sunshine, slick and clean. They package it with pretty plastic & ribbons and then feed it to us. A lot gets thrown away: the ribbons, the wrapping; culture becomes garbage, or it dies, and rots behind the refrigerator. But the new fluffy shiny stuff still gets churned out, and it gets forced between our teeth. And we are told to swallow it. We will not swallow. We will chew, and then spit. We will play with ourfood, and create something new and interesting from it (Detritus 1). The manifesto speaks of being force fed products, of wanting them because advertisements tell us to. It recalls the waste of consumer-oriented culture and yearns for more, refusing to accept waste as a replacement for substance. That is the nature of culture jamming, to show consumers another side to their reckless consumption and to open their eyes to the truths hidden behind layers of public relations and media saturation. In a very real way, culture jamming helps advertising to reclaim its morals. For too long, advertisers have danced around the realities of harmful and unsafe products with the trite eye candy of celebrity endorsements and catchy jingles. Culture jammers see the lies inherent in ads and turns them inside out to expose every falsity and half truth to the harsh light of day. They do this in an entertaining way, mimicking the practices of the advertisers themselves to bring their creations to the people, showing consumers the truth about a product and the campaign behind it. By revealing the nature of advertising to consumers, jammers are teaching the masses to view advertisements in the same way that its creators do, to see the negatives of a product as well as the positives and beyond that, to see the hidden agendas behind a campaign. For instance, a consumer who had been versed in culture jamming would recognize that the current ad campaign praising the Phillip Morris company for its charitable donations is in fact a way the tobacco company has devised to get around current laws prohibiting cigarette advertising on television. If all people were educated in this way, I think it would lead to an increase in ethical advertising, as well as a decrease in consumption of harmful products. In my future career, I want to do something I love, advertising, while remaining a moral person. After learning about culture jamming, I've come to realize that this is possible. The role of an ethical advertiser in today's society is to educate consumers through culture jamming. I will work as a mainstream advertiser by day, and create jammed versions by night. By doing this, I will be helping to teach consumers. Even though selling to educated consumers is more difficult for advertisers than the current system, I think it is worth it because it helps to protect people. Only when the masses have a working knowledge of the biases of advertisements will advertising truly be safe. Works Cited: Davidson, Kirk. (1996, September 23). When does creativity become deception? Marketing News, 12. Dery, Mark. (???). Culture Jamming: Hacking, Slashing and Sniping the Empire of Signs. In The Essential Media Counterculture Catalogue [Online]. Available: http://www.essentialmedia.com/Shop/Dery.html [2000, February 5]. Detritus: The Manifesto. In Detritus [Online]. Available: http://www.detritus.net/manifesto.html [2000, March 1]. Hearn, Wayne. (1994, January 24). Unhealthy education. American Medical News, 11. Kent, Christina. (1996, August 26). Tobacco firm pays for failure to warn. American Medical News, 1. Leonard, Mark. (1998, August 14). Sinister secrets of the ad men. New Statesman, 20. Mizrach, Steve. (???). Abrupt's Culture Jamming. In Cicada Hub [Online]. Available: http://escape.com/~cicada/culture2.htm [2000, February 5]. Neidsviecki, Hal. (Spring 1998). Pop: Product: Person. Adbusters [Online]. Available: http://www.adbusters.org/magazine/21/productperson.html [2000, February 5]. Rapp, Stan. (1992, November 5). Cigarettes: a question of ethics. Marketing, 17. Samorodin, Janet. (1996, October). Going up in smoke. NEA Today, 24. |