THE STORY OF LABRADOR

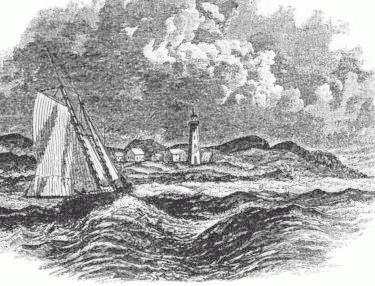

Point Amour, 1860: The Point Amour Lighthouse has been a landmark for visitors to Labrador since it was completed in 1857. It improved safety in the Strait of Belle Isle, a strategic sea route to Canada made dangerous by the presence of strong currents, icebergs, and unpredicable weather. It is just one of the many historic sites you will find in your Labrador adventures.

Labrador is a land steeped in a rich history that goes back thousands of years. There are numerous places that tell the story of the people who have, in their turn, lived in Labrador and harvested the riches of the land and the sea. This is a brief outline of that story, which you can learn more about by following the links to other web sites—or by exploring Labrador's historic sites when you visit! CLICK HERE for a listing of museums and other historic attractions.

The first people to make Labrador their home were the Maritime Archaic Indians. Beginning about 9,500 years ago, and for some 6,000 years, they inhabited along the coast, living largely off the produce of the sea: seals, seabirds, fish, and whales. Maritime Archaic sites are found all along the Labrador coast, from the Strait of Belle Isle in the south to Saglek in the north. The most striking Maritime Archaic site in Labrador is the mysterious burial mound at Point Amour. Here, over 7000 years ago, a 12-year old child was buried in a grave under a mound of stones, face-down, head turned to the west, with a large rock slab in the middle of the back. Various offerings were found in the grave, including knives and spearpoints, a bird-bone whistle, a bone pendant and a harpoon head. The sand around was stained with red ochre, and two fires had been built in the grave, one on either side of the body. Who was this child, and why was he or she buried in such an elaborate fashion? The true story of this child’s life and remarkable death have been lost in time. The Maritime Archaic culture too has disappeared. They may have merged with one of the later aboriginal groups to occupy the region. Or, according to one theory, they may have been the ancestors of the Beothuk Indians of Newfoundland, who, through disease and conflict with European settlers, died out in 1829.

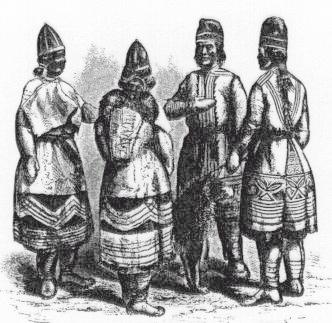

About 5,000 years ago, another ancient people occupied the interior. These were the Sheild Archaic Indians, likely the ancestors of the modern Innu (also known as the Montagnais and Naskapi). Their economy revolved around the caribou which was their staple food, and whose skins provided clothing and shelter. The caribou was the centre of traditional Innu religion, and the pivot around which the Innu culture revolved. Beginning in the late 17th century, Europeans established trading relationships with the Innu, exchanging European goods for furs. The Innu remained a predominately nomadic people, living off the land until the middle of the 20th century, when they settled in permanent villages at Sheshatshit and Davis Inlet.

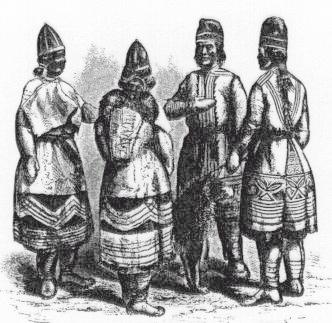

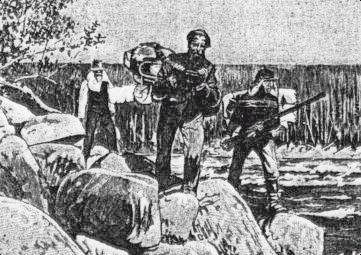

North West River, 1860: The picturesque traditional clothing of the Innu during the 19th century. These caribou-hide coats, or mishtikuai, were decorated using natural pigments. They were worn by shamans to help guarantee the success of the hunt. The elaborate decorations symbolized the power of the coat. Notice also the traditional embroidered caps, with different styles worn by men and women.

Three successive populations of Arctic Eskimo populations have inhabited Labrador. The early Palaeo-Eskimos or Pre-Dorset people arrived from the Canadian Arctic around 4,000 years ago. They occupied the coast north of Hamilton Inlet for about 1000 years before disappearing, probably returning to their ancestral homeland. Around 2,600 years ago, the Dorset Eskimo came into Labrador, eventually making their way as far south as Newfoundland, where they thrived. For two millenia they inhabited the coasts of Labrador and Newfoundland before they too mysteriously left the scene about 800 years ago. The memory of these Dorset people, named for the Cape Dorset on Baffin Island where the culture was first identified, is preserved in the modern Inuit legends of the Tunnit, a race of giants.

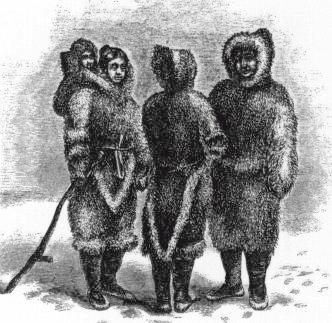

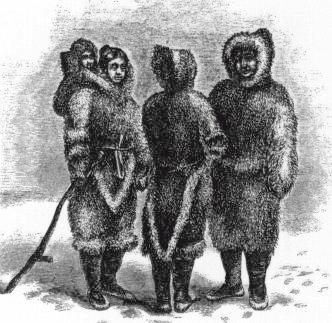

The third group, the Thule Eskimos, are the ancestors of the modern Labrador Inuit, having arrived in Labrador from the Arctic around the year 1300.They made their livelihood from both the land and sea. Seals were an important part of their economy and material culture. Seal furs and skins were used to make warm and waterproof clothing such as atigeks (parkas) and kamiks (sealskin boots). The Inuit of Labrador are the southernmost Inuit in the world, with related distantly to populations in Greenland, Arctic Canada, Alaska, and the Russian Far East.

Labrador Inuit, 1860: The Inuit were always known as master tailors, and until well into the 20th century Arctic explorers preferred Inuit-made clothing to machine-made European or American articles. Notice the distinctive tails of the women's coats, and the baby carried in the oversized hood.

IF YOU FIND AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE: Remember that archaeological sites are protected by law, and it is illegal to disturb them. Do not attempt to dig or recover artifacts from a suspected archaeological site. Pinpoint the site on a map, make a careful note of the type and location of artifacts found, and tie a ribbon or ‘flag’ to a nearby tree or rock. Report the find to the provincial Department of Tourism, Culture and Recreation at 1.709.729.2462. An archaeological site is a unique record of the past, and once destroyed, cannot be recovered. It is important that they are properly investigated, recorded, and studied so that the full history of Labrador can be known.

The first European visitors to North America were the Norsemen, who found their way to Labrador by accident from their colonies in Iceland and Greenland around the year 1000. They eventually established a settlement at L’Anse-aux-Meadows on the northern tip of Newfoundland, or Vinland. Labrador was their Markland, or Forest-Land. The Norse accounts mention long, white sand beaches, which have been identified as the Strand just north of Cartwright. This remarkable feature of an otherwise rocky and ironbound coast was known to them as the Furdustrands or wonder-strand, and to cruise its entire 40-mile length leaves no doubt as to why. The Norse occupation of Vinland was very brief, but there is some speculation that they may have continued to cruise to Labrador for furs and timber as late as the 1300s.

John Cabot made his first voyage of exploration in 1497, and may have landed somewhere in the Strait of Belle Isle. He is known to have cruised the Labrador coast the following year. During the three years 1500 to 1502, the Portuguese explorer Gaspar Corte-Real voyaged to the northwest Atlantic, visiting Greenland, Labrador, and Newfoundland. Greenland became known as Terra del Llavrador, after an Azorean llavrador or farmer who was on the voyage and spotted the landfall. The name evolved into "Labrador", and later shifted to the northeastern region of the North American mainland.

French navigator Jacques Cartier explored the Strait of Belle Isle in 1534. In a famous passage in his narrative of the voyage, he described the Labrador coast of the Strait of Belle Isle:

- Were the soil as good as the harbours, it would be fine, but this should not be called the New Land, being composed of stones and frightful rocks and uneven places; for on this entire northern coast I saw not one cartload of earth, though I landed in many places. Except for at Blanc-Sablon there is nothing but moss and stunted shrubs. To conclude, I am inclined to regard this country as the one God gave to Cain.

Beginning in the 1540s, whalers from the Basque region of Spain and France began frequenting the Strait of Belle Isle. They established a number of stations on the southernmost coast of Labrador, including the most important ones at Chateau and Red Bay. For half a century they dominated the region during the whaling season, and maintained skeleton crews during the winter to safeguard the shore facilities. In the 1580s the industry began to decline, and by the 1620s the Basques had all but abandoned Labrador. Archaeological work at Red Bay over the past 20 years has uncovered a rich record of their activities, including cooperages, dwellings, and tryworks where the whale blubber was rendered into oil. The most exciting discovery has been the wreck of a ship, believed to be the San Juan, on the bottom of the harbour.

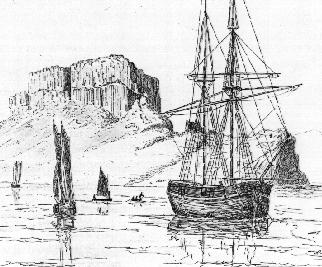

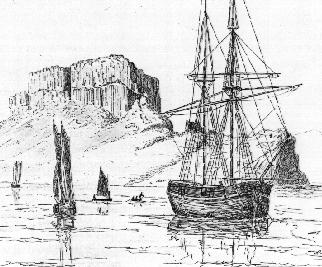

Henley Harbour, Chateau Bay, 1857: Showing the remarkable "Devil’s Dining-Table" that tops Henley Island. Chateau Bay was an important whaling, fishing, and sealing harbour for its successive Basque, French, and English occupiers. The remains of nearby Fort York, built in 1766 for the protection of the Labrador fisheries, can still be seen.

Starting in early 1700s, fishermen from New France began to frequent the southern coast of Labrador. Drawn by the cod and seal fisheries, and later by the fur trade, they established stations throughout the Strait of Belle Isle, many of which still bear French names: L’anse Amour (from L’anse aux morts, "Deadmen’s cove"), Pinware (from Baie noire, "Black Bay"), and Chateau (from Baie des chateaux, "Bay of castles"). This latter name derives from the remarkable basaltic table-lands on the main islands within the bay, which were prominent and familiar landmarks to early navigators and fishermen. These outposts of New France eventually extended as far north as North West River and Rigolet, where Louis Fornel established posts in 1743. The trade and fisheries were abandoned in the mid-1750s when war broke out between England and France, and the Gulf of St. Lawrence was no longer safe for shipping.

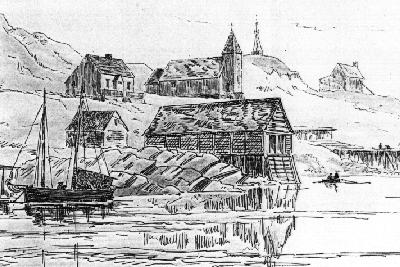

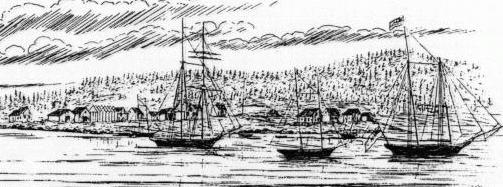

Battle Harbour, 1857: Battle Harbour is a seasonal fishing village on a harbour formed by two islands, just off the southeast coast. Long known as the unofficial Capital of Labrador, it flourished during the 18th, 19th and first half of the 20th centuries. The community has recently undergone a restoration to its mid-19th century appearance, and can be toured from neighbouring communities.

After the the English conquest of Canada, Labrador was placed under the jurisdiction of Newfoundland. In 1774 it reverted to Canada, only to be returned in 1809. Shortly after the Conquest, English merchants and adventurers began to occupy the coast, and within a few decades were joined by French-Canadian and Jersey interests as well. The most famous of these traders was Captain George Cartwright, who had stations in the Cape Charles and Sandwich Bay areas. In his Journal, he recorded his daily business, his dealings with the Innu and Inuit, and the natural history of the region in which he made his residence for 16 years. In Cartwright one can visit Flagstaff Hill, with its cannons at the ready, placed by George Cartwright to guard the harbour and settlement below, now named in his honour.

Capt. George Cartwright: Cartwright was a British Officer in India, who came to Newfoundland with his brother John in search of the Beothuk Indians. Thus began a career that led to a sixteen-year residence in Labrador as a trader and adventurer, with stations and outposts in numerous locations in southern Labrador, including the town that now bears his name.

The first Christian missionaries to Labrador were the Moravians, or Unitas Fratrum, a denomination which originated in Czechoslovakia in the mid-15th century. This early Protestant sect began its missionary work abroad in the 1730s, and as a result of its mission to the Greenland Inuit, came to Labrador in 1752. Its first attempt at establishing a mission met with tragedy when leader Johann Christian Erhardt and six other missionaries were killed near modern-day Hopedale. Further attempts were made in the 1760s, and in 1771 the Moravian Mission was established in Labrador, where it has continued to the present day. The first mission station was established that year in Nain, followed by Okak in 1776, Hopedale in 1782, and Hebron in 1830. The early mission buildings which survive at Hebron and Hopedale were prefabricated in Germany, shipped across the Atlantic, and re-assembled. Other Moravian stations were not as lucky: both Nain and Makkovik suffered disastrous fires, while Hebron and several others were abandoned. The most tragic fate was met by the station at Okak. In 1919, the Spanish Influenze epidemic raged around the world, and reserved its fury for the coast of Labrador, where it wiped out entire families. The Inuit had no immunity and were especially hard-hit; up to one third of the Inuit population of Labrador died in the epidemic. At Okak, 215 people out of a population of 263 succumbed to the disease. The survivors were relocated to other settlements, the station was closed, and every trace of it was burnt to the ground.

In 1834, a Hudson’s Bay Company servant named Erland Erlandson was engaged to find an overland route from the Company’s posts on Ungava Bay to those on the Gulf of St. Lawrence. He got as far as North West River, where he discovered French-Canadian traders operating in competition. Two years later, the HBC barged into the Labrador trade, and over the course of the 19th century edged out most of its competitors in northern and central Labrador. Its first posts were at Rigolet and North West River, in the district known as "Esquimaux Bay". The EB mark was a sign of highest quality, and commanded the highest prices at London fur auctions. Many of the HBC’s servants settled in Labrador after their service ended. They adopted the local ways of life, fishing, hunting, and trapping for a living. As the population grew, the trappers had to go ever farther inland to establish traplines. The most distant fur paths belonged to the "Height-of-Landers" who trapped on the interior plateau above the Grand Falls (now Churchill Falls.) A few remaining HBC post buildings can be seen today at Rigolet and North West River as reminders of the glory days of the Labrador fur trade.

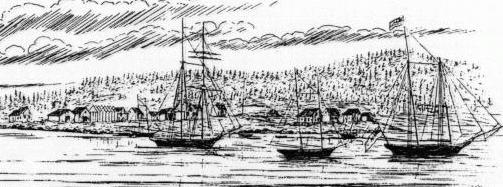

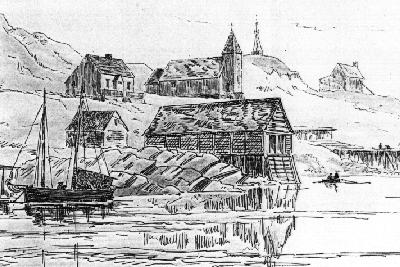

Rigolet, 1877: Rigolet was established by French-Canadian traders during the late 18th century; its name derives from a French word meaning channel, referring to its strategic location on the Narrows which connect Lake Melville to Groswater Bay. It was this location which guaranteed its place as the main Hudson’s Bay Company post in Labrador during the 19th and 20th centuries. During the mid-1800s, Donald Smith was the Company’s officer in charge in Labrador, and made his headquarters at Rigolet. His successes in the Labrador trade later propelled him to a career as a political leader in Canada, and was eventually elevated to the peerage as Lord Strathcona. He is perhaps most famous as the white-bearded, top-hatted man who drove the Last Spike in the Canadian Pacific Railway. A handful of the old post buildings remain at Rigolet today.

During the 19th century, a number of self-styled explorers and adventurers came to Labrador to try and win themselves a place in history. In 1887, Englishman Randall Holme attempted to ascend the Grand River to the Grand Falls of Labrador. He failed to reach his objective, but the ensuing publicity prompted a string of similar expeditions.In 1891, a party from Bowdoin College in the United States reached the Falls, and left a note in a jar tied to tree as a record of their visit, and suggested that others do the same. Subsequent visitors added their own notes to "The Bottle" until it was removed in the 1960s.

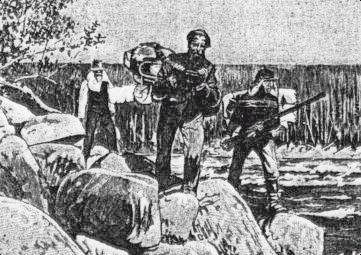

Tracking on the Grand River, 1891: The Grand River, known as Mishtashipu to the Innu, and renamed Churchill River by the Newfoundland government, is the largest river in Labrador. The first white man to see its famous falls was Hudson’s Bay Company servant John McLean in 1839. During the late 19th century, the area around and above the Falls was occupied by trappers from around the North West River area. After the construction of the Goose Bay Air Base in 1941 the trapping industry largely collapsed, and the long-distance trappers went to work at the base.

The most infamous of all the Labrador expeditions took place in 1903. Leonidas Hubbard, an American, together with his friend Dillon Wallace and guide George Elson, set off from North West River that summer, intending to travel upriver and overland to Lake Mishikamau and Ungava Bay. The expedition was a misadventure from the start. Elson was an experienced native woodsman from northern Ontario, but had no local knowledge of Labrador. The party could not engage a local guide, and just 40 miles out they took the wrong river, sending them hundreds of miles off the correct track. Their canoes overturned and they lost valuable gear. The wild fish and game they counted on to supplement their provisions was scarce. They never got as far as Mishikamau: after sighting the huge lake from the top of a distant hill, they abandoned the attempt and raced back towards civilization. Hubbard never made it. He died of starvation and exposure in a tent on the banks of the Susan River, while his Wallace and Elson pressed on in search of assistance. In 1905, his widow Mina Hubbard completed the journey her husband died trying to make. The cause of the Hubbard disaster is still vigorously debated today: would they have made it if they were better prepared? At North West River, you can look up the lonely expanse of Grand Lake that three men canoed up one summer's day in 1903... and that only two limped back down to relate their terrible ordeal.

Mina Hubbard: The American Leonidas Hubbard, self-styled adventurer and explorer, set off to "discover" a route from Hamilton Inlet to Ungava Bay. Ill-prepared and inexperienced, he starved to death on the trail while beating a hasty retreat from the Labrador winter. His companions, Dillon Wallace and George Elson, barely escaped with their own lives. Two years later his widow Mina, accompanied by Elson, completed the trek for him, while Wallace, whom she blamed for her husband's death, mounted a competing expedition along the same route. She chronicled her expedition in her book, "A Woman's Way Through Unknown Labrador", a classic of Canadian travel literature.

Living conditions among the Labrador 'livyeres' and Newfoundland fishermen were terrible during the 19th century. Sanitation was non-existant, and diseases such as tuberculosis were rampant. In 1892, an English doctor named Wilfred Grenfell made his first visit to the region, where his work continues to this day. He worked in Labrador and northern Newfoundland until his retirement forty years later. The organization he founded, the International Grenfell Association, was a dominant force in the region for most of the 20th century. It played an important role not only in health care, but in education and economic development as well. Grenfell 'missions' were at the centre of community life in places such as Cartwright, Indian Harbour, and North West River. Through the efforts of the I.G.A. medical staff, tuberculosis, once the 'white plague' of Labrador, was eradicated, and health, education, and living standards for many isolated communities were greatly improved.

Sir Wilfred Grenfell: Grenfell's efforts as a medical missionary on the Labrador coast were rewarded with a knighthood. He organized a medical mission to coastal residents and itinerant fishermen in a country where health and living conditions for many were horrendous. The organization he founded, the International Grenfell Association, ran hospitals, nursing stations, orphanages, and schools along the Labrador coast, in northern Newfoundland, and along the Lower North Shore of Quebec.

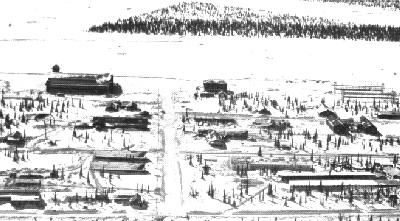

World War II had a dramatic impact on the lives of Labradorians. In 1941, the Canadian military built, in the span of a few months, an enormous air base at Goose Bay at the head of Hamilton Inlet. The great sandy plateau, located on tidewater, with excellent weather conditions, was ideal for an airport that formed a critical link in a chain of airfields across the North Atlantic. This air bridge between Europe and North America served the war effort by providing a supply line that the German submarines could not disrupt. The construction of the base turned the regional economy on its head. Where just months before, trappers and fishermen were struggling from the economic impacts of a worldwide depression and a global war, steady jobs and good wages were now available for the taking. Within a few short years, the subsistence economy that had ruled for two centuries had all but disappeared, and many settlements and homesteads were abandoned in favour of the new civilian community at Happy Valley. Goose Bay grew at an enormous pace during the Cold War years, with large British and American contingents joining their Canadian counterparts. While the Americans pulled out in the 1970s, British, German and Dutch forces began using the airport for fighter training during the 1980s.

Goose Bay Air Base, ca. 1942: While it continues to play an important role in both civilian and military aviation, Goose Bay was established as part of an aerial supply bridge across the Atlantic. The German submarine "wolf pack" scored tremendous losses against Allied shipping during the early years of World War II, leading to the development of the Northern Air Route across 'stepping stones' in Canada, Newfoundland, Labrador, Greenland, Iceland, and Britain. The wolf pack made its presence known in Labrador as well. Submarine sightings were common along the coast, and more than 40 years later a German weather station was discovered at the extreme northern tip of Labrador where it had been installed by a U-Boat crew.

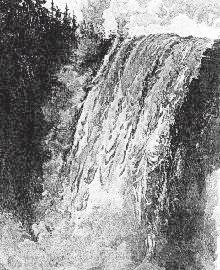

The 1950s saw the start of industrial development in the Labrador interior. Iron ore had long been known to exist in vast quantities. Its presence was noted by Louis Babel, a Catholic missionary to the Innu, in the 1860s. The vast water power at Grand Falls (now Churchill Falls) had been known since the first reports of their existence were made by Hudson's Bay Company officer John McLean. In the 1890s, Canadian government geologist A.P. Low travelled the region, and calculated the hydroelectric potential of the Falls. He forecast the development of the mineral and water resources of the region. The iron hills around Labrador City and Wabush were developed during the 1950s and 1960s, and account for most of Canada's iron ore production. The falls were harnessed in the late 1960s, and came into production in 1971. Around each of these new industries there grew new communities: Labrador City, Wabush, and Churchill Falls. With the opening of the Trans-Labrador Highway's western segment in 1992, these towns are gaining importance as gateways to the rest of the region.

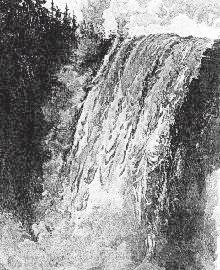

The Grand Falls of Labrador, 1891: At over 300 feet one of the most impressive natural wonders of the world, the Grand Falls of Labrador disappeared forever in the late 1960s when they were diverted for hydroelectric generation at the Churchill Falls station.

The 1994 discovery of a rich nickel/copper/cobalt find at Voisey's Bay prompted a flurry of new mineral exploration. Production of ore from this deposit is expected to begin within a few years, with secondary processing at a smelter and refinery at Argentia, Newfoundland. Meanwhile, construction is set to begin on the south coast leg of the Trans-Labrador Highway, while the existing portion of the road between Churchill Falls and Happy Valley-Goose Bay is being improved. The pristine and remote Labrador wilderness is becoming a little less remote and a little less wild with each passing year. In the late 1990s, Labrador is a land in transition. What does the new century hold in store?

![[MAIN]](main.gif)

![[NORTH COAST]](north.gif)

![[SOUTH COAST]](south.gif)

![[TLH]](tlh.gif)

![[NATURE TRAIL]](wild.gif)

![[LABRADOR LINKS]](links.gif)

![[MAIL FOR INFO]](info.gif)

This page hosted by

Get your own Free Home Page

![[MAIN]](main.gif)

![[NORTH COAST]](north.gif)

![[SOUTH COAST]](south.gif)

![[TLH]](tlh.gif)

![[NATURE TRAIL]](wild.gif)

![[LABRADOR LINKS]](links.gif)

![[MAIL FOR INFO]](info.gif)