|

|

|

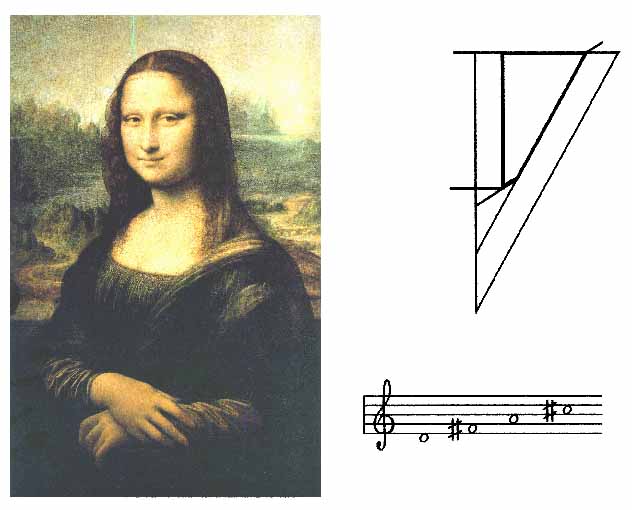

Fig. 6.

Graphic intonations in Leonardo da Vinci's Gioconda.

Left: the original image.

Right: the directional structure of the face of

Mona Lisa comprises a E-major chord with a large seventh (bold).

|

Another historical parallel arises between the introduction

of the diminished-seventh chord in music and that of Cubism

in painting, both occurring at the beginning of this century.

The precise graphic analogue of the diminished seventh

(do—mi flat—sol flat—si

double flat) is a square, which has all the aesthetic

potential of the musical chord [31].

Now, let us turn to the mystery of color, which for a long

time had been a subject of abstract speculations and arduous

controversy. I distinguish two aspects of any perception:

perceptive quality and coloring. While quality determines

what the thing is, coloring refers to details that do not

carry the main idea of a composition and can be varied in

different ways [32]. To be strict, I should

point to a specific level of perception at which some components

of the whole image are considered significant, while others are

not. For instance, the instrumental cast for a musical piece

may vary freely, allowing for numerous arrangements; however,

in contrast to this potential for variation there is the

composer's arrangement, which may often be specifically

intended. In the same way, an artist may put his or her

intimate thoughts and high symbolism into the colors of a

painting, but a wider audience may well form opinions about

it on the basis of a black-and-white reproduction; these

opinions then occupy their own niche in the culture. On

the other hand, one cannot apply color without form, just

as there is no arrangement without something to be arranged.

Even the most abstract play of colors or modulations of

sound is somehow organized in space (or pitch) and this

organization still obeys the logic of scale hierarchies.

Naturally, there are cases when color cannot be detached

from painting without qualitative changes, e. g. the

landscapes of Claude Monet. By the same token, one cannot

imagine Ravel's Bolero outside its arrangement for

an orchestra. The links between impressionism in painting

and music deserve deeper consideration than I can give them

here. However, the principal idea of both is to shift

attention to coloring, to make it play the role of perceptive

logic. As a complement to the shift of coloring onto

logic, pitch-like relations become highly coloristic,

losing their qualitative aspect. However, they can never

lose it completely, since an observer perceives any

variation of color as a spatial form, and nothing can be

perceived by sight that is not spatially organized.

The role of color in visual arts is mainly to build forms

[33], just as the primary role of an

instrumental timbre in music is to mark a specific pitch.

As W. Kandinsky noted, the boundary of two colors produces

a form [34]. However, color is not

the only way to produce visual forms. The same effect can

also be obtained by light attenuation, sculptural

techniques, use of the plasticity of the human body in

choreography, etc. The variety of the visual arts comes

forth in this range of possibilities. But the common

feature of all visual arts is their basis in angle viewing,

implying hierarchies of directional scales.

Thus, there is a new language with which to speak of visual

arts: that of scale hierarchies. There is, however, no need

to measure angles when analyzing a painting, a sculpture,

a gesture, etc. A little training gives one a sense of visual

interval, just as we hear a musical fifth to be a fifth,

and so on. As soon as such a sense is developed, one is able

to appreciate the music of lines and discover a new world of

visual aesthetics.

Universal Scaling

I have demonstrated how pitch-like relations generate scale

hierarchies in both music and the visual arts. There are some

indications that the same process takes place in poetry, but

a more thorough investigation in this field is to be completed

later on. It is my belief that hierarchical scaling and the

potential for mathematical modeling that it allows provide us

with a universal means of analyzing art. The application of

the hierarchical approach to rhythm or nuances of performance

requires somewhat different mathematics, but the work is in

progress, and there is no doubt that some scaling phenomena

are to be discovered there as well. One may ask, therefore,

whether universal scaling in the arts displays only a peculiar

regularity of aesthetic perception or manifests a more general

law. I suppose that the grounds for aesthetic scaling are

rooted in the hierarchical nature of human activity in general,

which, in turn, reflects the inherent hierarchy of the world.

Any creative impulse springs from some refolding of that

hierarchy, and there is no purposeless art devoid of any

objective necessity. Art is one of the means of joining

individuals to society, and no artist creates anything

purely for the sake of creation without regard for the

opinions of potential observers. In any case, the artist

is the first judge of his or her work and, as such,

represents current societal attitudes. But any two

individuals (even if one of them is a clone of another)

can communicate only on the basis of some logic —

in other words, a mode of activity brought to them both

as a means of social regulation. Hierarchical scaling

in aesthetic perception provides an example of such community.

References and Notes