|

(I am including here a summary of some of the relevant sections from the more "philosophically technical" page which is appended to this one, so that interested parties won't have to keep switching back and forth between these pages. However, if you want a bit more background on the origin of the concepts used in my analysis of non-metrical image writing, you'll also want to refer to the page "What Is Non-Metrical Image Writing?" , where concepts such as "partial objects" [which is outlined in the "Writing" section] are introduced).

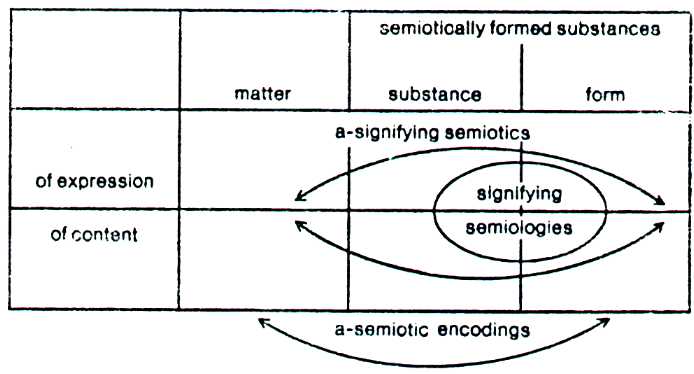

In defining the grammatological functions of non-metrical image writing, we noted (with reference to Felix Guattari's "The Role of the Signifier in the Institution", from MOLECULAR REVOLUTION) that a-signifying semiotics and a-semiotic encodings form (anasemantic) functional connections between the matter of content and expression, and the form of content and expression. By so focusing upon function, and thus bypassing any problematic concerns related to questions of meaning, we have also bypassed the intermediary semiological category of content and expression, substance.

|

|

When we last encountered this category of SUBSTANCE, it was when considering "movement of the infinite" as the truth holding between thinking and being: "...movement is not the image of thought without being also the substance of being." We will in the folowing section begin to define the nature of conceptual personae through an analysis of the linguistic category of SUBSTANCE. In our first derivation based upon these linguistic categories, we identified the SUBSTANCE OF CONTENT as PROXIMITY; and the SUBSTANCE OF EXPRESSION as IMMANENCE. Thus, our analysis of the nature of conceptual personae will examine relationships holding between situations of proximity and situations of immanence.

In our second derivation, we associated PROXIMITY with FEATURES and IMMANENCE with RE-MARKINGS. However, at this point, we can substitute two terms used by Guattari and Deleuze: with PROXIMITY being associated with DIAGRAMMATIC FEATURES, and IMMANENCE being associated with INTENSIVE ORDINATES. We will thus be considering conceptual personae in terms of interrelationships between the proximity of diagrammatic features and the immanence of intensive ordinates.

In undertaking such an analysis, we will soon find that the best way to proceed is through an insight noted in our initial consideration of the liguistic category of substance; namely, that the category of substance is bracketed by VIRTUAL POINTS and PARTIAL OBJECTS.

Meta-stabilities, as a formalization of re-markings (intensive ordinates), can occur as partial objects: and this can range from the territorial, camouflage patterns of animals, to any form of referentially indicative marking.

Thus, whenever we can find any virtual points we can directly associate with partial objects, we will have found a position characteristic of conceptual personae. Throughout this analysis, we will be considering how the conceptual personae we define express a sense of territory in reference to the area of the earth upon which they once did dwell.

"Subject and object give a poor approximation of thought. Thinking is neither a line drawn between subject and object nor a revolving of one around the other. Rather, thinking takes place in the relationship of territory and earth..."

It would also clarify for you greatly what I am doing here if you were to read: Perspectival Horizons Versus Event Horizons... because this is what my whole analytic approach is about! To our analysis, then... |

|

(THIS WILL BE THE NEXT SECTION I REVISE, AT SOME POINT IN THE FUTURE... {July 30, 2002})Now, let's apply what we have learned concerning how non-metrical image writing works - to an actual example of this form of writing. For this, I have chosen the first example of non-metrical image writing that I found: a little dime-sized stone that I fondly refer to as "The Three Feather Chief". The following analysis of the non-metrical image writing upon The Three Feather Chief stone will not be a complete one; we will only be looking at one aspect, one perspective, of this stone. Needless to say, a complete analysis would indeed be a lengthy process, due to the complexity of non-metrical image writing, and despite this stone's small size. Nonetheless, I hope this analysis will give interested parties a good grasp of some of the basis principles involved in interpreting non-metrical image writing using a post-structural, grammatological approach. Even in the limited analysis I am undertaking here, there will be many details within this example of non-metrical image writing that I will have to skip over; but, readers are encouraged to explore such details as they wish. The first question that arises with such an analysis is, “Where to start?” Although the best answer to this question is “Anywhere; just begin!”, I have chosen a starting point that I think will best serve as an excellent introduction to non-metrical image writing. To begin, then:

"...This was made by the Snow-On-Rock people. They use to live up the coast, up where the glaciers drop to the sea from the mountains. They use to live up where the streams and rivers start, at the base of the glaciers. Up in the mountains. Of course, there isn't much else up that way except ice and mountain; if you're going to live up there, that's what you've got to live with. So their name comes from the glaciers and the mountains there. It also comes from the stone work they were known for, where they used white rocks like this and uncovered images in the black stone underneath. They were considered to be responsible for the waters that feed the streams, and the streams are the lifeblood of the valleys.

|

|

One of the central assemblages of diagrammatic features upon this stone presents the face of a person (shown above). This face expresses a distinct happiness mingled with pride, presenting an expression I would have to associate with wisdom.

First, let us look at the features which present the mouth and eyes of this face. The mouth itself presents the outline of a very long flint knife, of the kind that has been found to be associated with the hunting of mammoth.

Such knives were used to sever the spinal columns of mammoth, above the shoulder blades. To the right of and slightly above this knife, one can indeed see images of the mammoth in question; but they are indistinct, and tend to disappear into the white background matrix of the stone. Here, we can see

our first interpretive principle at work: the singularity of the flint knife is associated with the virtual points that imply the mammoth.

There is also a concept here: taken as a mouth, the flint knife is of course associated with speech. We have already determined that the singularity of the flint knife functionally references the virtual points of the mammoth; We know that concepts, as intensive ordinates, tend to be distinctly durational in nature. So, combining the distinct location of the flint knife as it occurs in the position of a mouth; the fact that mouths speak; and the indistinct presentation of the mammoth as a collection of virtual points, we find: speech as a ‘transient occurrence’, words as a way of communicating which does not have a solid presence; and words as referring to things that are not immediately present.

Let’s consider the nature of this intensive ordinate (as a concept defined through a distinct duration) further. One component of the flint knife’s singularity would be the large members of the cat family found, to the left, at its handle. Very well and good; as a concept, this expression of 'transient occurrence' is the sort of thing we are looking for.

Next, let’s consider the eyes of this face that we have choosen to start our analysis from. Here, we can see quite clearly the figure of a person with an upraised knife (left eye), behind and slightly to one side of a large and solidly built animal (right eye), which is looking away from the person.

The slight variance in orientation between the two figures presents to us a perspectival expression of their co-relation in space. Thus, the virtual points associated with these singularities unite them as diagrammatic features within a common event: and this is an active narrative, not just a simple perspective. The animal on the right is facing one of the mammoth images; the virtual points of a mammoth’s tusk extend to the head/mouth of the animal, and the ears of the animal are alert. So, the singularity of the animal image enters into an association with the figure of the person holding the knife, through two sets of virtual points: that of the mammoth’s tusk, and that of the perspectival point of view holding between these two figures. Since the relationship between the mammoth’s tusk and the animal figure presents an event also implied by the upraised knife, we do indeed have here an instance of virtual points defining diagrammatic features within a distinct point of view. Now, what concepts can we find here? Within the presentation of these diagrammatic features as a point of view, the alert ears of the animal figure supply us with a definite partiality and a very distinct intensive ordinate; the upraised knife of the person also contributes a sense of durational suspense, of temporal connectivity.

The concept presented here is clearly one which is associated with stealth; for, the solid form of the alert animal certainly makes it look like a dangerous creature, and the relative position of the person (behind the alert animal, poised to attack) is that of someone who is being very careful in what they are doing. ‘Silent activity’ is the concept here, as the intensive ordinate of the duration presented within the partiality of the two figures toward each other. But there is something else we can note in this composition. The alert animal (possibly, a short face bear: see photo image at right) is directly associated with the virtual points of the mammoth’s tusk, while the figure with the upraised knife is separated from the singularity of the flint knife/mouth. We can modify our first concept through this; ‘transient occurrence’ becomes co-joined with ‘silent activity’ to suggest two things to us: one, that speech as a sound-producing activity can frighten animals away (the mammoth) or cause them to attack (the large, alert animal which does not avoid the mammoth, despite its tusks); and, two, that there is an association (articulated through the knife) of separation between the ‘transient occurrence’ conceptualized in reference to the mouth and the ‘silent activity’ conceptualized in reference to the eyes. This tells us: non-metrical image writing is “SILENT SPEECH”. There is a second narrative that we can compose from the two singularities which present the eyes of The Three Feather Chief. Instead of beginning with the virtual points associated perspectively with the diagrammatic features these singularities occur as, let's consider them as eyes: as our own eyes. If you look at an object that is to one side of your direct, central line of sight; and look at that object through one eye, and then the other, you will notice that this object will shift slightly. Any object will do this, because our eyes are offset. The shift you will notice in doing this is very similar to the offset perspectival relationship holding between the two singularities that present The Three Feather Chief's eyes. We can note a few relevant things about eyes here: eyes are each like the other, and one eye always follows the other. With this in mind, we can see that both the figure of the person with the upraised knife and that of the alert animal are presented as being very solid and hefty in their body forms. So perhaps what we are also being told here is that the figure of the person is following the figure of the alert animal: the person is learning how to hunt mammoth by watching the alert animal.

This interpretation presents us with a higher degree of consistency than our first interpretation, and it tells us some things that we should remember throughout our analysis of non-metrical image writing: Such a progression of understanding presents the interpretive movement which we undertake in going from diagrammatic features to intensive ordinates; but it also captures the increasing complexity of differential texture that any reading can reveal as holding between the relationships found to form: in linkages of sensory contrasts with singularities; of meta-stabilities with meta-narratives; and in general, of grammatological matters with grammatological forms of non-metrical image writing. In fact, we will see later that non-metrical image writing is designed to produce new and more complex interpretations with every subsequent reading. This is an aspect of its compositional nature, as a form of meta-narrative.

In introducing to us the differences between phonetic reference and the 'silent speech' of non-metrical image writing, the diagrammatic features that are the eyes of The Three Feather Chief demonstrate to us the basic characteristics of 'silent speech': This is a fundamental consistency which defines non-metrical image writing as a plane of immanence, through which concepts and conceptual personae appear.

Now, let’s follow this concept of ‘silent speech’, and see where it leads us. The next non-metrical grouping pattern that we will look at is one which connects the two previously discussed singularities, identified as the eyes of the face we began our analysis from, with a third singularity that mirrors the co-relational orientation of the first two. Here, the figure of the person with the upraised knife is central to and equidistant from two singularities, which are at equal angles relative to this central singularity. These three singular points are connected by identical sets of virtual points which create/present distinctly co-related positions. Together, these three singularities form the diagrammatic features of a new face: the face of an owl.

The new singularity introduced to us through the diagrammatic features which group together to form this owl’s face is that of a spear point.

Here, we should note that this image of a spear point is completely out of proportion with the figure of the person with the upraised knife, and the figure of the alert animal. These three singularities are not connected by the virtual point characteristic of a perspectival point of view. They are connected by virtue of the direct correspondence holding between their relative distances and positions; it is this relationship of symmetry that unites them as the virtual points characteristic of an owl’s face. Let’s look at the partialities holding between the singular objects so assembled into this owl’s face, and see what intensive ordinates might be presented here that we could compose into a further narrative related to ‘silent speech’. We have noted the concept of ‘silent activity’ as the intensive ordinate found in the partiality between the figure of the person with the upraised knife, and the figure of the alert animal. We also noted that hunting such a large, solidly built animal with a knife probably wasn’t a particularly desirable undertaking to involve oneself with; indeed, the inclusion of the mammoth’s tusk in this composition suggests a defensive aspect to this activity. So, the disproportionate size of the spear point within the context encompassed by the owl’s face suggests that, all things being equal (symmetrically proportionate), using a spear to hunt with is much more desirable (presented through a position which characterizes a point of view of much greater proximity) than hunting animals with a stone knife. Here we have the concept of ‘desired preference’. This is confirmed by the expression of the owl’s face: its eyes are half-closed, in a squint that is characteristic of pleasure. Within the context of the owl’s face, we can define a few more concepts. Owls are noted for their silent flight; their keen eyesight (attributed to their large eyes); and their deadly accuracy in hunting (attributable to their keen hearing but, that is a modern finding which shouldn’t be applied here). Thus, here we have aspects related to the nature of the concept, ‘desired preference’, which is associated with hunting by using a spear point: as an intensive ordinate, it is composed of silence, keen eyesight, and acute accuracy. These are necessary qualities, which hunting using a spear point shares with hunting using a flint knife; it’s just that using a spear for hunting is a ‘desired preference’. Also, hunting with a spear point is noticeably more owl-like, in that owls and spears both fly silently through the air. Again we have found a concept moving at infinite speed. 'Desired preference’, as composed of silence, keen eyesight, and acute accuracy, is implicated in our understanding of hunting with both spear and knife. And it is also very characteristic of the qualities necessary to the successful production of ‘silent speech’…non-metrical image writing. Our analysis of ‘silent speech’ has become clarified by leading us toward the concept of ‘desired preferences’…and that is also, toward the partiality of objects in relation to their intended uses. Our analysis is also taking us away from speech, and (as we shall soon see) into the realm of materially-based production. Let’s continue, with a closer look at the spear point. Spear ‘points’ are quite directional in nature; and this one is located noticeably closer to our next singularity than it is to the figure of the person with the upraised knife. Directly in front of the spear point is the figure of a mountain goat. The disproportionate size of the spear point is noticeable here, too; only now, given the directional aspect of the spear point, we can surmise something new from the virtual points holding between goat and spear point as co-related diagrammatic features: the relative distance at which a spear point is an effective weapon for hunting goats with. It is a distance greatly exceeding that of a stone knife; indeed, it is another kind of distance altogether: for, the farther one is from a mountain goat when a spear is thrown, the better one's chances of not startling the goat into flight...and the better one's chances of actually hitting the goat. Let’s look at the intensive ordinates that are characteristic to this distance, as it is expressed within the partiality holding between the mountain goat and the spear point. We have already seen that, on the side of the spear’s thrower, this intensive ordinate is primarily presented by a silence similar to that of an owl’s flight. On the side of the mountain goat, however, we find something new: the goat is shown as raised up on its back legs, with its front legs curled up; it is in the process of jumping.

Here we see the reason that the silence of an owl is needed: the throw of the spear will be counter-balanced by the mountain goat’s jump, should any sound startle the goat. Further, the spear point is shown as being physically closer to the mountain goat than it is to the person throwing the spear…even though, proportionately by relative figure sizes, the goat is farther from the spear point than the person is (suggesting the sort of distances at which hunting by spear point is effective). This suggests that the goat might have a bit of an edge in such a hunt. Silence is indeed required during such a hunt...and the precise nature of such a hunt is further expressed through the differential symmetry presented by the eyes of the owl (which we will consider in more detail a bit later).

Here we have a perfect example of the type of progression in understanding which is inherently presented through non-metrical image writing. As a reader's ability in hunting mountain goats with a spear increases, they can move from the first instance (and skill level) presented through the owl's face - hunting a stationary goat - to the next instance (and level of skill): hunting a moving mountain goat. Similarly, the reader/hunter moves from the differential symmetry of the owl's eyes - which also expresses the differential symmetry of The Three Feather Chief's eyes - to the central point of symmetry in the owl's face. This central position presents the symmetry of understanding between reader and writer: it is the point where the reader has learned and understood what The Three Feather Chief is teaching through the owl's face, as the person with the upraised knife learned from the alert animal in the earlier composition presented by The Three Feather Chief's eyes. Spear points do not arise in silence. One must be told how to make them, as well as shown the techniques involved. The making of spear points demands techniques also used in the production of the most difficult stone tool to make: the long flint knife. Similarly, the ‘silent speech’ of non-metrical image writing exemplifies that conceptually more elaborate paradigm of communication, human speech. As with a spear point, and unlike flint knives or human speech, non-metrical image writing can express thoughts over great distances of space and time…and so has characteristics which make it a ‘desired preference’ over speech. As for the mountain goat itself, there is a curious aspect to the presentation of its image that we should take note of: its horn(s) is shown as broken. We shall see what this tells us in a moment.

To the right of the spear point and the mountain goat, there are two other singularities. They are of roughly the same size scale as the spear point and mountain goat; and they are roughly the same relative distance from the eyes of the face we began our analysis with. This collection of singularities, displayed as three distinct instances arrayed across the forehead of the primary face presented here, are what I refer to as ‘The Three Feathers’; and, they are why I refer to this stone as “The Three Feather Chief”. The first "feather", then, is presented by the spear point and the mountain goat. The second "feather" presents what is called a microblade core. The third "feather" presents a granite ax or adze. Taken together with the flint knife which forms The Three Feather Chief's mouth, these singularities present a material history of the technological advances developed, for the production of stone tools, by The Three Feather Chief's people. Thus, the 'silent speech' of non-metrical image writing presents not only a material form of narrative, but a material history as well. Material substances and objects are not in themselves historical; they derive their historical and cultural aspects from the historical nature of the lived experiences, the event horizons of existence, of the people who use(d) them. However (and because of this), any act of material production is historical in reference to the people who undertake such production (as well as to the people who use the items so produced); so, when production techniques relevant to material can be differentiated, then our understanding of materially-based narrative can be expanded to encompass a material history, too.

Now, let's look again at the virtual points specifically associated with the spear point and mountain goat. We have already noted the proportionalities and distances that are related to these singularities within the context of the owl's face. There is more of interest here for us. Between the spear point and mountain goat we find something new; we find that both of these singularities express an active vectoring of a kind we haven't seen here before. This is particularly interesting in light of what we noted in our previous analysis of what a concept is; for there, we noted that "concepts...mark out intensive ordinates...as movements which are themselves finite". Thus, we can fully expect to find particularly well defined concepts here...and, they will tell us just how this form of 'silent speech' goes about 'hitting its mark'. The virtual points of the spear point are easily defined. They are associated with the vector of the spear's throw: the point the spear hits, as well as the force of the spear's throw, from the virtual point that the spear leaves (taken together, this defines a curve). The virtual points of the mountain goat are also easily found. They are the point the goat leaps from (its back legs) and the point the goat jumps to (its curled front legs). Taken together, these virtual points form two types of groups: starting points and end points. This nicely mirrors the symmetry found in the virtual points of the owl's face. The virtual points of the spear and mountain goat are also articulated, with the spear point's end position being the mountain goat's starting point. However, the dynamic of the mountain goat's jump indicates that this articulation can shift to anywhere in the spear point's trajectory, from start to end...determining whether the spear point actually hits the mountain goat or, misses it completely. What kind of diagrammatic features does this present to us? It presents a symmetry that contains a shifting articulation, in which only one position exists where the symmetry will be absolute: that being the position where the mountain goat's final jump occurs when the spear point hits it correctly. One spear throw, one final goat jump, one successful hunt: the symmetry of the owl's face. If the spear's end point does not coincide with the goat's starting point, the mountain goat keeps going; and the symmetry of the event does not match that of the owl's face. The hunt is not successful, due to some deficit on the part of the spear thrower relative to an owl-like attribute: silence, keen eyesight, or acute accuracy. In reference to 'silent speech' one can also note that these same qualities must be present in order for the writer's intent to have a proportionate affect within the reader's understanding: this is 'hitting the mark' in non-metrical communication. We can see here how concepts associated with the context of the owl's face can appear in a specific instance related to the diagrammatic features of the mountain goat and spear point. This is particularly interesting because it shows how intensive ordinates can either occur or, not occur upon an event horizon...indicating the presence of a meta-narrative in which one specific event-signature is defined by an integral meta-stability. The shifting start/end points for the movement vectors of the spear point and mountain goat constitute such a meta-stability of assemblage; and of the possible meta-narratives this articulation could generate, one composition is most closely intended by the context of the owl's face: that of a successful hunt. 'Accurately hitting the mark' is the concept that best collects the partialities at play upon this extended event horizon of meta-narrative. Indeed, two possible meta-narratives would capture here the absolute symmetry of the owl's face: as already mentioned, with the spear point ending where the mountain goat begins its final jump; and, in the case where the goat is already in motion, where the spear point is thrown in a way that "leads" the goat's motion, arriving where the goat is headed as the goat gets there. In this narrative, the arc of the spear and the jumping run of the goat are symmetrical in that they arrive at a common point at the same time...and it is at that instant which the symmetry of the owl's face is achieved. The diverging narrative symmetry (where the end point of the spear is the starting point of the goat) in which the goat is struck by the spear while standing still is the desired preference (here, the 'spear point' side of owl's face is preceeded by the 'alert animal' side); but the converging narrative symmetry of successfully hitting a fleeing mountain goat with a spear is more central to the essence of what an owl is. This converging symmetry is also characteristic of more advanced interpretations of non-metrical image writing, wherein new narratives are co-joined with established readings. This is a more developed level of skill. Let's look a little more closely at the intensive ordinates presented by the partiality of the spear point to the mountain goat. First, we see a 'specific tool for a specific task'. The spear point presents a (relatively) slow heaviness of force in this, along with a sharpness in contact. The mountain goat presents a (relative) quickness of reaction and adds a distinct variability to the result of the spear point's sharp contact of slow (in waiting for the result of the throw) heaviness. Here, we are starting to see the infinite speed of a plane of immanence's consistency in marking out the intensive ordinates of finite concepts. When the symmetry of the owl's face becomes the co-incident articulation of a spear throw's end with a mountain goat's end-or-start of (a) jump, then that lightning flash of a co-incident moment is an instance of a concept moving at infinite speed. Here there is also an infinite movement, for this scenario can happen forever, for as long as there are mountain goats and people to successfully throw spears at them. This infinite movement also sets in motion and defines such finite intensive ordinates as are associated with 'accurately hitting the mark': sharp contact of slow (through anticipation) heaviness; and quick, variable reaction. This is a very important family of co-related concepts: for, as we move through the development of this 'silent speech' in the 'specific tool/specific task' context of a materially-based narrative (and material history), we will find that intensive ordinates of contact and speed are concepts that are fundamental to our understanding of non-metrical image writing. They are also concepts which, as practices related to material production, are essential for the successful manufacture of stone tools and weapons: they define the act of accurately striking stone in order to produce stone tools. Thus, such concepts are integral to our understanding of the truth of being that is the conceptual persona whom I call The Three Feather Chief. I mention this conceptual persona here because, there is something else I would like to point out about the spear point/mountain goat position of our ongoing meta-narrative. We began at the flint knife/mammoth position, where we noticed a relationship of territory-to-the-earth which suggested that mammoth might have been becoming scarce as a food source. That too, it turns out, was an instance of 'a specific tool for a specific task'. Now, our reading of this 'silent speech' suggests that a new food source might have replaced these disappearing mammoth...and that a new territory was being defined by this conceptual persona, upon a new section of the earth. Here, 'silent speech' tells us that the 'desired preference' found in the 'specific tool for a specific task' which is the spear point/mountain goat assemblage has taken us, from wherever mammoth roamed (probably in the low coastal flats found only during the height of an ice age), into the surrounding mountains.

The mountains are where mountain goats are found - obviously. However, mountains are not always just mountains. Sometimes, mountains are also volcanos. Volcanos are where one finds that type of volcanic glass which is the stone we call obsidian. Obsidian can be used as what are called microblade cores...which is the second singular position in the material narrative extending across The Three Feather Chief's forehead. As mentioned earlier, the three singular positions on The Three Feather Chief's forehead are defined by virtual points which establish their symmetry relative to The Three Feather Chief's eyes and mouth. This co-relation establishes these singularities positionally as diagrammatic features, within a narrative that is materially based. The second singularity (or feather) presents the image of a microblade core. With this singularity, a new element can be noted: instead of a simple outline of form, the microblade core presents the inclusion of internal detail. A white line can be seen extending into the form of the core, and a white polygon can be seen near the end of this line. What is this?

Microblades are small, regularly-shaped pieces of volcanic glass that are broken off from large blocks of obsidian. These large blocks are referred to as 'cores'. The microblades themselves are sharper than the finest modern surgical steel...up to 100 times sharper than steel. The microblades are separated from a core by applying pressure at the edge of the core. This pressure is applied using some thin, pointed, resilient object... such as the horn of a mountain goat (or, in other situations, the antler of a deer). You will recall that earlier, it was pointed out that the horn(s) of the mountain goat was shown as being broken. This is why: horns from mountain goats were used to manufacture microblades of volcanic glass from obsidian cores. Let's consider the virtual points apparent in this first section of material narrative. We noted earlier the dynamic vector of the mountain goat's jump. This vector is further presented in the separation of a piece of horn from the mountain goat. On the microblade core, we have a presentation of a mountain goat horn; and the separation of a microblade. Between the spear point/mountain goat and the microblade core, we have quite a bit of space...the most space that is apparent between any of the singularities within the section of material narrative presented here. And although we see the horn/separation motif with both the mountain goat and the microblade core, the motif is both inverted and shifted in its second occurrence. Whereas we had previously been dealing exclusively with singular details presented through a black image outline, we now see internal detail in white...an inversion. And whereas the horn is first presented as separated from the mountain goat, in the second instance it is presented as separating a microblade from an obsidian core...a shift. So, our virtual points here define separation, inversion through internalization, and a material shift...and all of this within a relationship of symmetry (separated horn, separating horn). Now we are starting to see something quite interesting: the diagrammatic features that we are defining are starting to conceptually divide the surface upon which they occur. The diagrammatic features are being co-related dimensionally, instead of just spatially. The dimensions so employed are being defined by partiality; in this specific case, through a symmetry which expresses difference. We have seen this sort of differential symmetry before, in relation to the eyes of the owl's face, and the eyes of The Three Feather Chief. Perhaps, then, we can here also expect to find ourselves presented with something a little more interesting than just a surface reading of perspectival, diagrammatic features. This is certainly the case. The differential symmetry we are dealing with here is presented through the spatial dimensions of the stone's surface...and just a little bit of the dimensionality of the stone's depth. This is a two dimensional presentation that implicates, but does not present, a third spatial dimension. This does not cause the virtuality of a third dimension to become actual; it makes the virtuality of the third dimension consistent with the first two. Here, a fraction of the third dimension is rendered consistent with the presentation of the first two dimensions. We are now dealing with diagrammatic features which are being presented through a fractal space. Our diagrammatic features have become diagrammatic fractals.

(Most people will not immediately grasp the implications of such a fractal display of information. But the sad truth of the matter is, most people today do not even think in three dimensions. If we have learned anything from our look at such things as: To continue: Let's see what kind of concepts we encounter associated with diagrammaticly fractal features. Since the virtual points of our diagrammatic features present the partiality of a fractal space, defining the partiality of the objects presented here should be quite easy. We have an internalization and a separation holding across a symmetrical shift. This in turn is applicable to the intensive ordinate of the mountain goat's jump, and applies to the separation of microblades from their obsidian core. The concept that results, the intensive ordinate so defined, is one which is already moving at infinite speed upon its own event horizon. What we are being told here is that the reactive, variable jump of the mountain goat, relative to the strike of the spear point, is internal to the goat: it is an immanent characteristic of the mountain goat, and defines the nature of the goat's being in the world. This is true to the point that, if you take just a part of the mountain goat, if you just take the horn which always points toward where the goat jumps (up), this part will when separated from the goat cause other things to jump as the mountain goat could and did. The intensive ordinate of the mountain goat's ability to jump is concentrated in the horn; and if the goat's horn is separated from the goat, it can impart the goat's jumping ability into other things that it is subsequently connected to...such as the obsidian cores it is used to make microblades jump from. Now, that is a concept moving at infinite speed! It leaps with the mountain goat, it separates with the horn of the goat, and in causing microblade to separate from obsidian cores, it makes them leap, too. It is interesting to note here that this symmetry of separation occurs within another lightning flash of a moment, when the microblade is shown separating from its core. This moment is similar to the articulating point where the spear point hits a stationary mountain goat, which makes its last jump (and to the symmetry involved in successfully hunting moving goats): the moment of symmetry when the owl's face flashes into being. But the moment of symmetry when a microblade separates from its core is not a moment when the owl's face asserts itself. This is a different event horizon. This is a different intensive ordinate. The duration might be of the same scale - that of an instant - but the intensity is greater. This is a different family of concepts. This is a different 'specific tool for a specific task'. This is a different material epoch. We have shifted from removing flakes from a stone and producing a tool, to using the pieces flaked from a stone as tools themselves. The entire relationship between the whole and the parts which had previously characterized the making of stone tools has become inverted. And everything else changes with this, too.

(As an aside, I want to point out that the idea that a mountain goat's ability to jump is localized in its horn is a 'philosophic' concept. It is the sort of 'philosophic' concept that can all too easily be mistaken for a 'scientific' function. Thus, where Aboriginal culture will often attach a 'spiritual', conceptual value to specific animals or parts of animals, one often finds that in traditional Asiatic medicinal practices a 'scientific', functional (health related) value is placed upon animal parts. To continue: Microblades flaked from obsidian cores are incredibly sharp. You can make a lot of them from a single piece of volcanic glass: their production is a much more efficient undertaking than removing and discarding innumerable stone flakes from a single flint spear point or knife. Used as a weapon, obsidian points will slice into and kill anything that needs to be eliminated. All edged weapons kill by causing blood loss; so the sharper a weapon is, the better it works. This is particularly true of arrow heads. Microblades are also easily produced as items which are small and uniform in size. This means that they can be mounted together in a wooden handle, to create a saw. With such a saw, it is possible to make easy and efficient use of very large trees. Microblade technology enabled the production of houses, canoes, totems, masks...an incredible array of products and artforms and innovations and ideas. The techniques developed with microblades for the working of wood were also applied back upon the working of stone, leading to further developments in both the production of stone tools and the production of non-metrical image writing. The efficiency of microblade production allowed for the freeing up of a large amount of time previously dedicated to the production of stone tools. The efficiency of microblade use allowed for an unprecedented expansion of material technologies. Microblades changed everything; and this will become abundantly clear as we examine the families of concepts associated with microblade production.

Microblades didn't just allow the easy creation of wooden artifacts. The very idea of using microblades in a saw was in itself responsible for another new material epoch. The sawing motion used to cut wood is another intensive ordinate associated with microblades. This concept of cutting by sawing was in turn applied to stone. It was discovered that solid files created from pieces of sandstone could be used to cut and shape pieces of igneous granite. And that is the last singularity portrayed upon the forehead of The Three Feather Chief: a solid granite ax or adze. That is the third great epoch in this material narrative and material history. As important an advance as microblades were over flaked flint tools, they had one drawback in common with flint tools. Both were made by flaking stone; and so both were prone to easy breakage. That changed with the ability to make solid granite tools. Suddenly, it was possible to produce tools that didn't shatter with any hard impact. Having tools which do not break is much more efficient than having tools that are easy to make. Unbreakable tools introduce an element of persistence, of permanence, to a culture. But, I'm getting a bit ahead of myself here. Let's look at the virtual points associated with the second and third singularities in this material narrative, the obsidian microblade core and the solid granite ax. The granite ax also shows detail internal to the black outline of its form. In this case there is a single re-marking of its surface, which angles across the lower left corner of the ax. This is where a wooden handle is attached to the ax. Relative to the microblade core, we notice that the ax is in such close proximity to the microblade core as to actually make contact with it. As diagrammatic features, the microblade core and the granite ax are connected. This suggests that they are parts of one continuous thing...as indeed they are. Suddenly, the white mountain goat horn on the microblade core becomes a mouth (where the ringing sound of a microblade being flaked is produced); the white microblade becomes an eye (the eye must keep track of where each microblade leaps upon being separated from its core); and the granite ax becomes the tail...of a fish.

Saws produced from microblades and axes produced from granite can be used to make canoes from wood. Canoes can be used to catch fish. Fish from the sea are as plentiful as microblades from an obsidian core, or the granite that axes are made from. Again, the concept of 'specific tools for a specific task' has brought us to a new source of food...and allowed access to a new territory upon the earth. Here, we again see a differential shift across a symmetry, such as the one which we noted as occurring between the singularities of the mountain goat and the microblade core; in this case, as a shift from two objects into one figure through a symmetry of intensive ordinates: sawing actions, and flaking actions (in microblade production, and in creating the area where the granite ax's handle is attached). Note that the symmetry here is between intensive ordinates, not diagrammatic features. This is also somewhat consistent with the meta-stability which is expressed through the symmetry of the owl's face, and its contextual narrative relative to the process of hunting mountain goats using spear points...as well as with the differential positioning presented by the eyes of The Three Feather Chief. In each case, we have a differentially consistent application of the concepts being presented through their relevant diagrammatic features. Here, though, it is the intensive ordinates themselves which are presented as differential yet, united by a central singularity of understanding. The flaking and sawing activities associated with microblades are sharp and fast (as intensive ordinates), as are microblades in their use; those associated with a granite ax are hard (heavy) and slow (as is its production and use). What is particularly interesting here is the interpretive shift which occurs when the intensive ordinates of the microblade core and those of the granite ax are united as, respectively, the body and tail of the fish. Here we have differential intensive ordinates co-presented to express the immanent nature of an animal. Where we have before seen virtual points used to connect diagrammatic features, we now see intensive ordinates being similarly employed to define the characteristic difference in kind of an animal. Now, instead of the reader's relationship of understanding being defined with reference to that of the conceptual persona who produced this example of non-metrical image writing, the difference in kind between an animal - the fish - and the reader is being presented through an associative unification of intensive ordinates within a distinct singularity. The concept of a fish is being presented through intensive ordinates which characterize it. The central position of singularity, which had previously been employed to establish relationships between reader and writer, is now being used to define the inherent temporal characteristics of an animal's difference in kind relative to the reader (and writer). The animal's difference in kind is being presented as an event horizon which unifies the characteristic durations of the intensive ordinates it naturally produces through its way of being in the world. The fish's mouth and body snaps and flashes when the fish bits: this part of the fish expresses intensive ordinates characteristic of the microblade core. The fish's tail methodically moves back and forth with heavy force, or produces sudden, hard motions: this part of the fish expresses intensive ordinates characteristic of the granite ax. The difference between the waveform motion of a fish's tail and its expressed transference into the fish's body, is similar to the difference in the intensive ordinates characteristic of microblades and granite axes. And when the microblade core and the granite ax are united to form the singularity of the fish, the internal features of the microblade core suddenly shift. The goat horn becomes the mouth of the fish, and the microblade itself becomes the eye of the fish...at infinite speed, a new event horizon characteristic of the fish is formed when the singularity of the fish is created. Upon this new event horizon, a new aspect of meta-narrative appears, as a compositional expression of the content of the singular meta-stability of the fish. The act of fishing, made possible by the production of canoes and through the use of microblades and granite axes, is also inherent in the intensive ordinates presented here. Fishing is a pastime characterized by a lot of slow, ponderous waiting (not to mention paddling)...leading to a sudden, intense burst of activity when the fish is caught. We are now dealing with an event horizon and meta-narrative defined in terms of the intensive ordinates of an animal, rather than those of a person. So, the method of fishing employed here was, in all probability, "jigging": a slow, regular, methodical up-and-down movement of the fishing line followed by a sudden tug when the fish bites (to set the hook). This implies, of course, the use of some sort of fishing line, and fishing hooks.

Please note here that the utilization of fishery resources PRESUMES the use of forestry resources as a DIRECTLY CAUSAL PREREQUISITE.In the symmetry between the intensive ordinates that constitute the way of being of the fish and the intensive ordinates of fishing by 'jigging', we can again see the symmetry presented by the owl's face...centered this time upon the act of setting the hook as the fish bites. The differential symmetry of the owl's face occurs upon the event horizon defined by the intensive ordinates of the fish. Through this, we can be certain that the symmetry of the owl's face does indeed present us with an association of diagrammatic features and intensive ordinates which constitutes the conceptual persona of The Three Feather Chief...as conceptualized by The Three Feather Chief himself. We have again encountered 'a specific tool for a specific task'...but his time we are finding such a relationship contextualized and defined by the animal refered to, instead of by the person making the reference. And that is a lot more interesting and informative than what we would be told through archaeology or anthropology. It is almost as interesting as some of the things we could learn directly from First Nations Elders.

We are starting to see that the relationship between the conceptual persona that The Three Feather Chief presents, and the territory this person conceptualized in their being upon this earth, is consistently presented through the symmetry of the owl's face. The owl's face is a meta-stability which supplies grammatical structure to the meta-narratives in which it is integrated. A little later, we will see that this presentation also includes a sea otter; but for now, we should note that this relationship between territory and earth always presents to us 'a specific tool for a specific task'...as the focus of this form of 'silent speech'. In looking at the intensive ordinates associated with the fish, and how these intensive ordinates present the concepts found upon the event horizons associated with the fish, we have noticed that the intensive ordinates associated with animals are being used to define the meta-narratives we are encountering. This shouldn't be a surprise, for we have noticed this tendency throughout the meta-narratives we have encountered here. We have been learning from animals in our growing understanding of 'silent speech'; and we have been learning through our eyes (which is again not surprising, since animals can not teach us anything by speaking to us in a phonetic language). We have crossed an interpretive threshold to find that animals can define the event horizons that people become a part of, as surely as people can define the event horizons that animals become a part of. Here, we are about to see that our initial reading concerning the diagrammatic features which present the eyes of The Three Feather Chief was indeed a meta-stability supporting the structure of further meta-narratives; for the lessons to be learned from non-metrical image writing teach not only how people can vary the events they are part of (by learning from animals): it also teaches how animals will vary the events people are part of, and that this variance is an aspect of the essential differences between animals and people (as different kinds of things). In other words, people are not the only singularities that create and direct event horizons in the world. This is a fundamental and important shift in our interpretive analysis of non-metrical image writing. We find this shift becoming established in our analysis at the point where we move from the spear point/mountain goat assemblage to the microblade core and ax/fish composition. Here, we noted some other interesting aspects in our analysis of non-metrical image writing. We noticed the introduction of image elements that are internal to the singular forms which present diagrammatic features. We noticed the introduction of a fractal dimensionality. We noticed shifts in both diagrammatic features and event horizons attributable to the singularities which are the (non-metrical) differences-in-kind of animals. We noticed intensive ordinates functioning as virtual points might, and that in functioning this way they established meta-narratives associated with the meta-stabilities they were found within: instead of diagrammatic features functioning thus, we found intensive ordinates that are associated with the partiality of a meta-stability establishing the form of meta-narratives. We will see why all of this is occurring at this point in our analysis, of non-metrical image writing's presentation of a material narrative, as we approach the end of our analysis. Instead of just defining the the substance of being for a conceptual persona, we are beginning to define narrative form through the differences in kind which characterize immanences within the world. We are finding that people are not the necessary center of everything that happens within the world, and are not alone in defining territories upon the earth. You might be surprised at how far this stage of non-metrical image writing was developed; it produced some very interesting forms of narrative composition. It presents narrative formalizations that express what the world teaches of its own nature...what we now call "science". It says what immanences are of the world, not that the world is an immanence of being human. Now, that's REALLY geophilosophy! But, I won't be exploring this development of non-metrical image writing here; that is the sort of meta-narrative which tends to be found in more complicated examples of this form of image writing. Besides, look at how much I've had to write in order to interpret the seven or so singularities we are examining here. I have well over 1,000 pages of research notes just leading up to this point in my overall analysis...and then lots after!

Instead, let's return to the granite ax that is the tail of the fish; let's see if any of the interesting developments we've just noted in relation to non-metrical image writing can be found here. Our granite ax isn't a particularly complex object; but it does have an internal feature. We can take note of the place where the handle attaches to the ax; so, we know in which direction the ax is pointing. Since we know where the ax is pointing, we can define at least one virtual point for it. And when we move in the direction of this virtual point, we find another singularity. This singularity is the outline form of a saber tooth tiger. We can easily find a virtual point for this animal by following in the direction that it is looking. There, we find a third singularity: an arrow head, which clearly presents an internal detail that shows where it is flaked in order to be attached to an arrow shaft. Since the arrow head is pointing back at the saber tooth tiger, let's stop here and see if these three singularities form the diagrammatic features of anything.

They do. With the granite ax as a nose/mouth, and the saber tooth tiger/arrow head as eyes, they form the face of a bear. This bear itself presents an event horizon through non-metrical variance: when the position of the bear's nose/mouth shifts from the singularity of the granite ax to the singularity of the saber tooth tiger, the diagrammatic feature of the bear's eye which had been presented by the saber tooth tiger is instead presented by a great white shark (with the arrow head remaining a diagrammatic feature common to both instances of the bear's face, as the other eye).

This is an interesting development in non-metrical image writing: here, a non-metrical grouping pattern is used to expresses the nature of the bear, as a distinctly different kind of thing; and to present the bear, not as a simple singularity but, as a meta-stability. Here we can see one of the fundamental ways in which differences between kinds of things will be used to produce meta-narratives within non-metrical image writing. Now, we are starting to see where that which we had earlier noted as occurring within meta-narrative, in relation to the fish singularity, can lead. A characteristic non-metrical variance of an animal, a way in which an animal varies from itself within time and so presents its difference in kind, is being shown here. We will return to this later, but I would just like to mention that what we are seeing here has a specific name: it is called a "movement-image", and it is conceptually quite different than the "time-images" (durations as intensive ordinates) which we have so far encountered. This is a very important distinction, because from this point on the event horizons of meta-narratives will present non-metrical grouping patterns that become increasingly more complex (and thus more useful for presenting information).

(Movement images are not encountered within modern visual communications until the transition from stationary to mobile film camera units, when cinema abandonned strictly stage-determined modes of theatrical expression/presentation and began to explore its own essential properties. The occurrence of time images and of movement images is inverted between film and non-metrical image writing, due primarily to their differences in mediating substrates. But for now, let's return to the fish, and its granite ax tail, to see what intensive ordinates we can find associated with the diagrammatic features of the bear's face. The intensive ordinates associated with the granite ax that seem to be most applicable to the nose/mouth of the bear are those related to the sawing motion used to cut the ax from a larger piece of granite (found in the back-and-forth motion of the bear's nostrils when it is 'sniffing' at something), and related to the action of flaking the area where the ax handle is attached. Both of these intensive ordinates are heavy, solid, certain, regular, and direct...like the motion of a bear which smells fish. Noting that the bear's nose/mouth, the granite ax, and the fish's tail are all expressed by the same singularity, we can suggest the concept being expressed here: it is, simply, 'grabbing the tail'. This is an important part of fishing successfully, for the fish being presented here appears to be a giant halibut. In order to land such a fish by bringing it into the canoe, you need someone who is 'as big (and strong) as a bear' to grab the giant halibut by the tail with the same suddenness, force, and surety of a bear (in a heavy, solid, certain and direct fashion). This person must also be as attentive as a saber tooth tiger, and as swift as an arrow. One other thing is being told to us here, related to the intensive ordinate of the bear's sniffing nose. Black bears (unlike grizzly bears) can be dissuaded from an attack by smashing them on their very sensitive noses. A solid granite ax would be better for this than anything else would be. Since the arrow head we have noted points in more than one direction, let's 'follow the arrow' here and see where it leads us in our analysis of 'silent speech'. As we proceed from the meta-stability of the moving bear, we will be bringing with us something that we have learned about the co-incidental occurrence of singularities. If we combine what we have learned from the singularity of the fish tail/granite ax/bear's mouth with what is presented by the saber tooth tiger as bear's mouth/bear's eye, we find an important insight into the nature of meta-narrative. When a singularity expresses co-incident occurrence as a meta-stability, it establishes the variance characteristic of a meta-narrative. This is because such a variant singularity supports a number of event horizons, and so produces relationships characteristic of those which hold between meta-stabilities and meta-narratives. We had previously noted that such relationships are characteristic of partial indeterminacies associated with sensory contrasts; but now, we have found another way in which they are formed.

[An example of partial indeterminacy within sensory contrasts, as it relates to singularities, can be seen in the three instances of a single image presented below: depending upon the lighting and the angle at which the image is viewed, it can express 1) a dog, 2) a bear, or 3) a saber tooth tiger. Needless to say, each particular image has its own event horizon of meta-narratives associated with it. The very fact of this singularity's variability, however, itself has a meta-narrative associated with it...pertaining to situations of mistaken identification or, rather, to how quickly events can change their character when the animals (components) involved change].

Note that in this, we have described a grammatological function which bypasses the linguistic category of substance, where diagrammatic features and intensive ordinates are found (in that no specific diagrammatic features or intensive ordinates are demanded in order that this process function in general). This is not to say that we are abandoning these two very important aspects of our interpretive analysis; it is just to point out that we are indeed working with another anasemantic function characteristic of this grammatological system of writing. This systemization has again shown itself to be fully capable of supporting written communication and conveying information without making use of phonologically-based significations of referential meaning. The bottom point of the arrow head directs us back to our over-all starting point, and to the collection of virtual points which constitute the mammoth. Here, perhaps, is the reason that the mammoth disappeared: the introduction of arrows, facilitated by the wood-working technologies developed with the use of microblades (as applied to the production of bows and arrow shafts), led to their demise. In that the arrow head points to both the saber tooth tiger and the virtual points that imply the mammoth, I think that this would be a fair supposition to make. It also suggests that a certain temporal and territorial cyclicity is being expressed in the compositions of non-metrical image writing; and we will return to this in due time.

Let's consider the saber tooth tiger's return to the beginning of our narrative analysis of 'silent speech'. As a singular aspect of the meta-stability which is the bear's face, we can note that the saber tooth tiger shifts from the position of the bear's mouth to that of the bear's eye; and that this occurs as the shark-as-eye leaves the grouping pattern presenting the bear's face. This is also where the granite ax enters the grouping pattern of diagrammatic features which present the bear's face.

Microblades, as tools for working wood, enabled their users to easily shape wood for a variety of purposes. Wood, with its regularly spaced banding of light and dark rings, would provide a wonderfully consistent matrix through which to express anything that could be presented in terms of sensory contrasts between light and dark. The ease with which expressive techniques could be developed in working with wood allowed such techniques to stabilize into consistent approaches for productive expression; these compositional stabilities could have then been transferred into the narrative techniques used to produce non-metrical image writing on stone. Thus, the development of microblade technology in all probability led to an incredible series of advancements in the grammatological expression of non-metrical image writing. That this occurred just when microblade technology also allowed for the easy access of seafood resources is probably not a coincidence. Seafood has been proven to contain rich supplies of specific molecules that are essential to neural development in the human brain. Granite, as utilized for tools through the sawing techniques developed with microblades, provided a permanently stable and randomly variable substrate for writing...which demanded the highest degree of conceptualization imaginable, in order for it to be re-marked into communicative consistencies. So the granite ax, in its connection to microblade technologies through the production of canoes and the utilization of seafood, also extends developments in the expression of images from the consistencies of a wooden substrate matrix into the differential texture of non-metrical image writing: and this occurred just when food resources had become more plentiful (allowing for more leisure time) and more healthful (allowing for better physical development). In the context of the bear's face, in presenting a shift from the mouth to the eye, our saber tooth tiger is indeed telling us something about the 'silent speech' of non-metrical image writing. This is the point where we must cease thinking of communication as an exclusively spoken event; this is the point where writing asserts itself as a distinct and fully established method for conveying information...in its own right, as its own way(s) of being. Here, we must even consider the possibility that the long, long history grounding non-metrical image writing (associated as it is with the material production of stone tools) may even supersede, in part, that of spoken languages... and that the conceptual demands made by the complex articulations of non-metrical image writing may have selectively favored the evolution of neural structures which allowed us to develop the ability to form conceptually complex, articulated speech. Had we not fully realized the variant nature of singularities during our initial analysis, the saber tooth tiger's shifting position within the context of the bear's face, coupled with the differential singularity of the granite ax, would have alerted us to this by this point in our interpretive analysis. So, on a second reading of The Three Feather Chief (as directed by the multi-directional indications of the arrow head), we would have realized that the singularities of The Three Feather Chief's eyes have two co-joined event horizons. We would have grasped the second, less perspectival and more conceptual reading, wherein the figure of the person with the upraised knife, the alert animal, the reader's eyes and the eyes of the conceptual persona who is The Three Feather Chief are all partial to a meta-stability articulated by the directly differential sensory contrast found between one eye's field of vision and that of the other eye. When we found the owl's face, we would have realized that hunting a mountain goat was being presented as having two successful approaches: the easier route of attacking a stationary goat; and the more difficult, skilled route of attacking a moving goat. With the microblade core, we would have realized that the intensive ordinates expressing the fish are also expressive of the act of fishing; and with the granite ax, we would have found that the movement image of the bear biting the fish's tail directly expresses an intensive ordinate as the actual event of a narrative: that concepts can be directly expressed as the content of the meta-narrative, as presented through meta-stabilities. Thus, meta-stabilities can intentionally and conceptually compose the event horizons of a meta-narrative: when the concept of the bear grabbing the fish's tail is presented through the singularity of the granite ax, the internal, re-marked detail of the stone flake that shows where the ax's handle attaches presents a unity between diagrammatic feature and intensive ordinate which stabilizes the movement image of the bear's shifting grouping pattern (of diagrammatic features) into a specific event horizon within an overall meta-narrative. Here, we see concepts not just as structural elements within non-metrical image writing: we are seeing concepts as the intentional product of non-metrical image writing. This, beyond a shadow of a doubt, proves for once and for all that non-metrical image writing is a fully developed system of writing in its own right (and there is more proof, which we shall come to later).

In other words, the saber tooth tiger is showing us how non-metrical image writing shifts communication from the mouth to the eye. This is not to say that non-metrical image writing functioned in isolation from human speech; quite the contrary. The First Nations have a very, VERY long tradition of oral histories. Given that one person can learn from what another has written, and that non-metrical image writing teaches more with each reading, it only stands to reason that more than one person reading the same example of non-metrical image writing will produce even more insights. These insights can be refined by discussing them, and comparing them with the readings of yet more people. This approach is inherent within non-metrical image writing, because it is a grammatological form of differential texture. Non-metrical image writing is differential in its form of expression from its very point of inception: because when a piece of granite is cut into two pieces, two new and differentially matching surfaces are produced. They are (were) connected by physical continuity; but they are slightly different from each other, in the random grain patterns of the stone matrix which they present. This is another reason why all readings of non-metrical image writing are multiple: at the productive point of origin for the substrate matrix this form of writing employs, in the lightning-flash of separation when the base material is obtained, there is a differential presentation of the substrate matrix. This in itself contributes to the initial complexity of non-metrical image writing, as a form of communicative production...and can be seen throughout our current analysis within the differential symmetry of the owl's face.

As Derrida noted in reference to the differential textures found throughout any grammatological analysis, absence is always implicated within traces of presence. Thus, any differential texture within non-metrical image writing always carries some trace of its "other": the differentially symmetrical surface associated with the moment of any such specific surface substrate's production. This can be clearly seen in the meta-stability which presents the movement image expressed through the grouping patterns which constitute the bear's face. This is an event signature (of a bear) which establishes a specific difference in kind within meta-narrative. Here, we can say that when a substrate of random rock grain patterns is conceptually re-marked into diagrammatic features which are characteristic of immanence (as contrasted with diagrammatic features characteristic of a spatial perspectivism), then the intensive ordinates of the concepts so employed establish a meta-stability which expresses a distinctly conceptual partiality: a partial dimensionality which presents event signatures that create meta-narratives uniting territory and the earth by establishing very specific forms of event horizon. This concept of partial dimensionality, first developed through the wood-working techniques discovered with the advent of microblade technology, was extended during the encounter with the differential symmetry presented by the matching pieces of separated granite commonly produced during the third material epoch of First Nations culture. At this point, the strong conceptual resonances between: Thus, the movement image expressed through the meta-stability of the bear's face presents to us the essence of meta-narratives characteristic to non-metrical image writing. Here, we can see that such a form of image writing need not be anthropocentric in nature; and although this particular example is somewhat anthropocentric in its expressed concepts, it certainly isn't very anthropomorphic. It should be noted here: in that granite is associated with the THIRD material epoch of First Nations' culture, and in that The Three Feather Chief stone is composed of granite, we must assume that a VERY long period of First Nations history extends back BEFORE the point where The Three Feather Chief stone was produced. This clearly establishes the importance of the First Nations' traditional oral histories, and the importance of the First Nations' Elders who maintain this tradition of oral history. Writing in any form is merely a supplement to lived experience, and the tradition of an oral history is much closer to the immediacy of lived experience than writing is. Thus, we must also consider the relation between the 'silent speech' of non-metrical image writing and the oral traditions of First Nations' histories. It is said that politics occur whenever there are three or more people involved in any discussion. One person reading non-metrical image writing is not political. Two people, each with their own tendencies to singularize the sensory contrasts of their individual perceptions, and each reading another person's non-metrical image writing and discussing their interpretations, IS political. It is the sort of politics of a nature that we call democracy. It is neither a wonder nor a coincidence that the First Nations developed democratic socio-political institutions, which were the model upon which the Founding Fathers of the United States of America based their democracy. I would also suggest that the current attitude of the established archaeological and anthropological communities (in Canada) toward the oral histories of the First Nations is characteristicly anti-democratic.

(In fact, I am starting to suspect just how strongly the field of archaeology has been influenced by some of its earliest and most influential proponents...who also happened to be members of the German Nazi Party, and who were intent upon finding and securing the 'Holy Grail' in order to exploit it for purposes of political propaganda, thus demonstrating Nazi racial "superiority"... As to the most recent developments regarding Kennewick Man:

- Date: Thu, 21 Jun 2001 18:24:36 -0700 Here are the thoughts of a Kah-milt-pah elder regarding the decision in the Kennewick Man case of yesterday. Please pass this on to whomever you folks feel will benefit from reading it. Thank you. -Long Standing Bear Chief

Mr. John Jelderks I am certain that, as members of the First Nations begin to compare the sort of analysis I have outlined here with the structural aspects of their spoken languages, the structural affinities and conceptual resonances between non-metrical image writing and the spoken languages of the First Nations will become readily apparent. There is no doubt in my mind on this point: the two will be able to support and stabilize each other...as they have always done. Perhaps then, the non-Aboriginal community will finally come to realize that the oral histories of the First Nations express conceptual relationships between intensive ordinates: they are not a form of mythology, they are a form of geophilosophy. Consider:

At this point in an analysis of non-metrical image writing, we would need a more complex interpretive matrix than the collection of grammatological concepts we have been using, in order to accurately express the conceptual intricacies found within the meta-narratives of non-metrical image writing. We would need an interpretive matrix which is less linear, in its expression of the progressive derivation of conceptual interrelations, than the one based upon grammatological functions that we have been using to get started in our analysis of non-metrical image writing. We would need an interpretive matrix that more adequately expresses the non-metrical essence of composition which this form of image writing presents to us. We would need an interpretive matrix based upon the traditional, conceptual Medicine Wheel used by the First Nations. Actually, two traditional forms of Medicine Wheel are employed at this point: the first is an external, physical assemblage of relationships for expressing diagrammatic features consistent with the earth's presentation of its empirical, spatial nature; and the second is an internal, conceptual composition of relationships for expressing the intensive ordinates consistent with territorial presentations of the existential, temporal nature of consciousness. Taken together, the two form a differential symmetry through which accurate event maps were created that presented territorial aspects of existence within partialities of the physical earth's dimensional expanse. And this is where things become really interesting, because this is where we find the formation of grammatological structures proper to non-metrical image writing in-itself, as a distinct and consistent form of written communication. I won't be going into that here, since I'm almost out of free space for my web site, and I can't afford to pay for a larger site.

It is unfortunate that I can't seem to locate any funding for my project, since I've come across some pretty amazing things related to this area of non-metrical image writing; but, I guess I'll just continue sharing these insights with members of the First Nations exclusively. Well, that's not my loss, and it certainly isn't theirs, either. It is a loss, though, because I am sure such insights will be found to have applications in other fields of inquiry...such as molecular biology. But of course, I alerted responsible parties in the United States (who would be able to do something positive and productive with such a previously unknown linguistic paradigm) to this possibility about seven years ago since, time and again, it has been proven to me that such matters are far too important to be left to the self-interested, narrow-minded, short-sighted and whimsical dictates of Canadian authorities. (Oh, thanks for the P.E.T. scans. I would imagine that computer technology, coupled with wavelet theory, is finally getting to the point now where simulating the shifting molecular configurations of cellular surfaces to the necessary degree of complexity is almost possible).

(In Canada, of course, a person could conceptualize the possibility of a consistent descriptive systemization which might function more accurately than the old, metrical "lock and key" metaphor used to explain interactions on cellular surfaces; but in Canada, this would end up being turned into - through governemnt funding - 'a way for virtually touching the fabric of clothes over the Internet'; and then into (indirectly government funded) cybersex: and then, of course, there would be various levels of police who would quickly become involved since locks, keys, and cells could only refer to "prisons" which means that the person in question absolutely would have to be stopped at whatever they were trying to do (any excuse would do, really) since it could very well be a massive jail break that was in the making... no, it wouldn't take long before someone was 'figuring out' what that person was 'REALLY up to'.