Here are some more images of North American hominids...

The Origin of Writing

Writing emerged directly from the creation of tools. At some point in our distant past, when our ancestors began to shape stone toward specific uses, they also took the first steps toward inventing writing. Shaping a piece of stone into a tool involves deciding which parts of that stone to remove in order to create the shape of the tool needed. Parts of that stone are usually removed by striking the stone with another rock, and so knocking flakes of unneeded rock off of the stone being shaped.

Deciding where to remove flakes of rock from a stone, determining how and where to strike that stone in order to remove the proper flakes, demands that the surface of the stone be closely examined and interpreted, so that the structure of the stone's grain and its internal properties of cleavage can be understood. The origin of writing resides in this very act of interpreting the natural grain of stone, in order to make stone tools.

It is a very small step to take, between flaking rock chips from a stone in order to make a tool, and reshaping the natural surface grain patterns of a stone in order to create an image. Remembering the shape of a tool one is attempting to make; remembering the shapes and the natures of the animals one will hunt with that tool; remembering the faces of the people who taught one how to make that tool and how to hunt: all these memories, and more, flood the mind that is engaged in creating that tool. Random grain patterns, on the surface of the stone being used, resonate with these memories within the patterns of stone grain being so interpreted. The tool maker sees parts of these memories peering out of the stone: and concern with the stone's subsurface properties, with its variable densities, hardnesses, resistances, and weight as well as with its unseen planes of cleavage and its overall balance, shifts toward an interest in the partial features suggested by the stone's random grain patterns. Soon, small alterations to that random grain pattern are being made, aligning the grain patterns more closely with the features they make resonate within the the tool maker's memory.

Writing is born.

Thus, the first form of writing which our species developed was a re-marking of images from our existential experiences...a re-marking of these images onto the natural, random grain patterns of stone. This form of writing arose directly from the techniques of material production developed in the making of stone tools; and so it is more closely related to the material from which it is produced than to the sounds of speech that we usually associate with writing. It is an image writing that presents the perception of events directly, as the experiential features that suggest such events most strongly. It is not a phonetically-based system for linking words with the objects they refer to; it is a system for assembling perceived features into composite images of events.

Over time, and in many places, this form of image writing gave rise to glyphic systems of writing. Eventually, many of these glyphic writing systems became integrated with the phonetic speech patterns of the people who used them. Distinct glyphs came to represent definite sounds; and eventually, phonetically-based writing systems were created from this.

But that was not always the case; and it was not necessarily the case. Even when it was the case, the structural rules of writing that govern how sounds are combined into words still show traces of an origin within the visual context of a materially-based production. Even English, as a written language, would not function as it does without the spacings between words (historically, this is a somewhat recent innovation to this language which was borrowed, as much of the English language is, from elsewhere) and sentences...and without punctuation (which very clearly shows a graphemic origin).

Non-Metrical Image Writing

I can not truly describe the nature of this form of image writing without considering, along with what it is, what it is not. What this form of written language is not, despite millenia of constant use, is: known and accepted as that which it is in it's own right.

After wave after wave of epidemics swept through the First Nations populations in the period following European contact, killing many of the Elders who knew this writing best; after early missionaries banned the possession of these curious, small, spotted stones because such stones resembled 'gambling dice'; after a century dedicated to the brutal suppression of Aboriginal culture through the Canadian government's system of church-run residential schools (a systemization of terror designed not only to wipe out the memory of Aboriginal culture from the minds of the First Nations children who were forced to attend...but designed to be so painful, so sadisticly evil that such children would in later years avoid even thinking about THE REASON they had forgotten their culture)...

The Sins of the Fathers

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A3729-2000Oct13.html

Innu member Bart Jack, a negotiator for the tribe,

says he was abused

by a priest who is now practicing in another

community.

By DeNeen L. Brown

Washington Post Foreign Service

Sunday, October 15, 2000; Page A20

SHESHATSHUI, Newfoundland –– She fears God, as the

priests

taught her.

So much so that when Elizabeth Penashue starts to talk

about the

abuses inflicted by priests and the church upon her

people, the Innu,

she issues only a whisper. The words won't quite come.

She fears God

will strike her down if she speaks against a priest.

Rain beats on the canvas tent in which she is staying

on a retreat

with other Innu. Finally, she says, "It hurt me. I

think priests just

like Jesus. But it was not only me. I saw him with my

friends in the

classroom. I saw. I saw . . ."

For years, rumors circulated in Canadian society of

awful things

happening in the church schools where many thousands

of native

children were taken, sometimes forcibly, during a

two-century-long

government effort to turn them into European

Canadians. In the 1990s,

aging former students began stepping forward with

their stories, and

what they said triggered a full-blown national

self-examination.

This summer, four major churches in Canada issued a

blanket apology

to

native people in the Atlantic province of

Newfoundland, asking

forgiveness for what the churches acknowledged were

centuries of

sexual and psychological abuse in schools the churches

ran. Leaders

of

the Anglican, Presbyterian, United and Roman Catholic

churches in

Newfoundland issued the apology to right wrongs that

they said church

officials committed.

"We are embarrassed and sorry for the suffering that

you, the

aboriginal people, have endured since the arrival of

our ancestors

500

years ago," James H. MacDonald, the Roman Catholic

archbishop of St.

John's, told about 500 people gathered in an old

school building in

St. John's, Newfoundland. "We ask your forgiveness. .

. . We long to

learn from the dark moments of our history."

The ceremony was part of the Jubilee Initiative, a

national church

campaign organized by a Roman Catholic nun, Sister

Emma Rooney, who

said she wanted the churches to acknowledge the

suffering they caused

Canada's native people.

Early settlers thought it was right to show native

people "how to

worship and how to work and how to dress and how to

speak," said

Gerry

Marshall, administrator for the Lantern Christian Life

Center and a

colleague of Rooney. "It was acceptable over the years

to use abusive

methods to do that, physical abuse. They were made to

learn our

language, to learn English . . . to read our books . .

. learn to

worship our gods. Instead of recognizing that we all

travel the same

journey and share the same God, we were narrow-minded

as white

people."

The Canadian government has reached similar

conclusions. In 1996, a

royal commission concluded that the problem went

beyond attempts to

snuff out native culture. Thousands of students died

in horrible

conditions at residential schools, it found, and

thousands more were

physically and sexually abused in the effort to

"elevate the savages."

In 1998, the government tried to make amends,

apologizing for

forcibly

preventing natives from speaking their own language in

schools, on

reservations or in communities where only native

children were

required to attend. That year Canada's Indian affairs

department set

aside $227 million for a healing fund to be used by

Indian

communities. But much of that money remains unspent.

Since the public apologies, churches across Canada

have been hit with

billions of dollars of lawsuits by tribes whose

children attended

church-run schools. Some children said that they were

wrongfully

imprisoned; others have said they were physically,

emotionally and

sexually abused at schools.

In 1998, the federal government settled 220 claims

involving priests

and nuns who had been convicted of criminal abuse. The

suits continue

to proliferate. The Anglican Church recently said it

may go bankrupt

as a result of payments to former students.

The program began in the early 1800s, when day schools

and more than

80 residential schools were opened across Canada for

native children.

"Residential schools were regarded as a better way to

break the ties

with the family and have a more direct educative and

assimilative

impact on the child," said Jim Miller, history

professor at the

University of Saskatchewan and author of "Shingwauk's

Vision: A

History of Native Residential Schools." Shingwauk was

a native chief

who in the 19th century requested residential schools

for his people,

thinking it would improve their lives.

Children were taken away from their families,

sometimes for as long

as

eight years, Miller said. He called the schools

"complete failures."

"They didn't educate kids," Miller said. "They had a

terrible

emotional impact on the children. . . . The kids were

raised in an

emotionally sterile environment. They emerged as

people who didn't

really know how to be parents."

Children were beaten "to the extent that they suffered

serious harm."

Children were locked in dark closets. Some children

had their hair

cut

for running away. "One of the most notorious cases was

in

Saskatchewan, where one supervisor made a whip with

five belts and

beat children he did not like," he said. The

government finally

decided to phase out the schools in 1969, prompted by

growing

resistance among native groups and the fact that the

swelling native

population was making it more expensive to run the

schools.

The abuse first received major public attention in

1990, when Phil

Fontaine, then head of the Assembly of Manitoba

Chiefs, went public

to

say he had been a victim of abuse in Catholic

residential schools.

His

statement encouraged others to tell their stories.

The churches' apology in Newfoundland this summer

renewed the saga

between white Canadians and churches and the native

people they tried

to change.

There is "no denial in churches" about the abuses,

said Andy den

Otter, professor of history at Memorial University of

Newfoundland in

St. John's.

"I think people believe the stories that aboriginal

people tell them

at face value," den Otter said. "By and large, that is

what we were

saying in the statement. We accept these stories. . .

. Even if a

particular story may have an element of exaggeration,

it is based in

a

legacy of abuse. . . . As a Christian, you accept

stories of abuse

and

you ask for forgiveness."

In Labrador, which is part of Newfoundland but borders

northeastern

Quebec, about 20 claims have been filed. Jack Lavers,

a lawyer

representing Innu people here, said abuse in day

schools in Labrador

affected three generations, beginning in 1950 and

continuing until

three years ago. Local Innus feel it led to myriad

tragedies: murder,

suicide, drug abuse, gas sniffing and alcoholism.

Peter Penashue, president of the Innu Nation, went to

the ceremony in

St. John's, where he was the only native leader who

refused to accept

the apology. It is not yet time for forgiveness, he

said, because the

churches have not sat down with the people to whom

they are

apologizing.

"What is it that you are apologizing for?" he asked

the church

officials. "Are you apologizing for the time a young

man, a

10-year-old boy, [was sexually abused by a priest],

only for the boy

to go home and be slapped by his mother and to be told

priests are

people of God? Or are you apologizing for the time one

of the elders

was pushed out from the church because he had a

nervous breakdown and

the priest said he was a man of the devil?"

Bart Jack, 49, a negotiator for the Innu, said he was

abused from age

6 to 13; many incidents occurring in the school called

Our Lady of

the

Snows or at the priest's house, which was near the

church and

graveyard. He said the priest who abused him is now

practicing in

another community, despite what authorities know about

his past. "The

white man's law," Jack said, "says, 'Unless you are

found guilty, you

are innocent.' "

At the campsite of an Innu women's retreat recently,

there were more

people with stories like that, including Rose

Gregoire, 52, who said

the apology was at first insulting. "Some of us

victims haven't even

forgiven ourselves for what happened to us, let alone

forgiveness for

our offenders," she said.

"We have been made to stand naked in front of a priest

when we were

very young and we could not do anything to defend

ourselves,"

Gregoire

said. "The Catholic Church teachings have made my

people fear God. .

.

. We were looking for love and to be cared for, to be

fed and

clothed,

and instead we were sexually assaulted as children by

the priests.

"Forgiveness? I have my doubts," Gregoire said. "Maybe

acceptance,

but

not forgiveness yet, because they robbed us of our

lives, like they

stole everything else from us."

(Such circumstances were by no means confined to Canada. Currently, in Australia:

"Aboriginal leader Lowitja O'Donoghue is urging the Federal Government to adopt a Canadian model in its treatment of indigenous issues.

Speaking at a national conference on human services, Professor O'Donoghue said the reconciliation process in Australia was currently "walking along a fault line".

She said Australia needed to take a more mature and honest approach to facing its history.

Professor O'Donoghue says that had happened in Canada in 1998, where the Government backed a Royal Commission with significant funding for projects to record indigenous history, and to address cases of sexual abuse.

"The Canadian Government has established that this was

widespread, that it commonly occurred in institutions where indigenous people were taken, and that it happened to thousands of people over decades," she said.

"It therefore provided $350 million as part of the gathering strength policy."

This money is dedicated toward a 'Healing Fund', designed to help the victims of the abuses common in residential schools in their efforts to recover from those experiences.

Canada's Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples found that residential schools, which Aboriginal children were FORCED to attend during most of the twentieth century, were: poorly built and maintained; that nutrition in the schools was deplorable; and that the crowding and sanitary conditions turned them into incubators for disease. These conditions led to the abuse, neglect, and death of an "incalculable" number of children. In 1907, a limited survey of a fraction of the schools found that one-quarter of the 1,500 students never left alive. One school, Kuper Island in British Columbia, had a 40% death rate over its 25-year history. Duncan Scott, a deputy secretary of Indian Affairs, estimated in 1914 that "50% of the children who passed through these schools did not live to benefit from the education which they received therein." This education was often minimal, and focussed on teaching children English and Christianity; studies were often restricted to the bible, with children spending a lot of their "study" time scrubbing floors and performing other menial tasks. On top of this, there was the abuse: the sexual exploitation of the children by school officials was common; and children found using their Aboriginal language were often beaten and, in some cases, had their tongues pierced with needles);

Schools For Killing Off Culture

28-07-1999, 10:46

By Thomas Sarri. Translation: Christian Moe

STORY

More at:

ARCHIVES

Among the indigenous peoples in Canada, there is talk of three things the white man has done to subjugate the indigenous peoples. The first was killing

the buffalo. The second was spreading epidemics among the indigenous peoples. And the third, and perhaps the most efficient for its purpose, were so-called residential schools.

At the end of the 19th century, the so-called residential schools emerged from cooperation between the Church and the state. The aim was to 'save the children from the life of the savages to a Christian civilization'. Already at the age of three to five years, the children were forcibly taken from their parents and placed in the schools for at least ten months every year.

"They stole the children, and our entire culture along with them," says Loraine Jackson of the Peigan tribe.

The schools were a part of the government's policy of assimilation, which aimed to change their traditional attitudes, culture, religion and language. Only European faiths and worldviews amounted to anything. Even the children's family names were changed to names like Smith and Jones.

The destructive school system rapidly expanded in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1931, there were 80 schools in the country. The schools were characterized by poor mental and sanitary conditions. In some years, close to one fourth of the children died from this misery.

The residential schools existed for 100 years. Most of them closed during the 1970s, though the last school shut its doors as late as 1984.

...and on top of all of this (and much more, besides), the 'advances' of modern psychiatry's "understanding" of human consciousness made speaking of "stones that tell stories" tantamount to an admission of mental illness (after convincing most people not to trust the contents of their own consciousness unless their perceptions and thoughts were sanctioned and supported by an almost religious adherence to the archive of psychology):

this form of image writing is, simply, NOT RECOGNIZED BY THE ACADEMIC COMMUNITY OF CANADA.

In fact, the very existence of this form of writing is BEING IGNORED.

Although, at least, there have been a few recent changes in the way in which the field of psychiatry is being applied within the context of Aboriginal culture (in some areas):

HOSPITALS OPEN DOOR TO NATIVE TRADITIONS;

Mohawks advise MDs on alternatives to 'white man's ways'.

By Douglas Quan. Ottawa Citizen; Friday, April 14, 2000: page F3.

In an effort to combat the number of mental health problems that go misdiagnosed, two Ottawa hospitals have set out to work with Mohawk natives to better understand traditional native approaches to mental health issues.

In a sacred ceremony held yesterday, representatives from the Royal Ottawa Hospital, the Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario and the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne agreed on a framework to better address mental health care issues for First Nations peoples.

Under the agreement, mental health services will be provided according to native healing processes, but in conjunction with mainstream models.

"It's about coming together and addressing their needs according to what their culture demands", said Anne Marie Bourgeois, a clinician-therapist at the Royal Ottawa Hospital's children's outpatient department last night.

"Up until now...we've been trained the white man's way. Now, the services will be provided in culturally appropriate ways."

Ms. Bourgeois said dreams and voices figure prominently in native spirituality.

But a mainstream mental health practitioner who is not versed in native culture, may end up diagnosing someone with these visions as schizophrenic.

This agreement, Ms. Bourgeois said, sets out a framework for psychiatrists to more actively and effectively treat native people with mental health problems. Hopefully, this agreement can play a role in stemming the number of suicides among native youth, she added.

(But they still don't seem to be addressing problems stemming from the material conditions common to most Aboriginal communities-JM)

Under the agreement, two members of the reserve will be required to accompany the patient during the assessment phase.

"Just because we're using modern medication doesn't mean they won't use their traditional sweet grass or smoke," said CHEO CEO Garry Cardiff last night.

"What goes on in medicine is what goes on in your head not just what goes on with the injury. By them doing what they have grown up believing coupled with what we've found scientifically to be supportive, we hope to bring together the best of both worlds."

There are about 10,000 people living on the reserve at Akwesasne, located along the St. Lawrence River south of Cornwall.

The title of yesterday's agreement was "Kahswentha", stemming from the first agreement signed between the Iroquois and the Europeans 400 years ago.

That initial agreement was symbolized by the Two Row Wampum Belt whose patterns told the story of two nations, each with their own values and belief systems, but moving together in the same direction without one encroaching upon the other.

This principle lies at the heart of yesterday's agreement. Among the key components of the plan are commitments to:

- establish accessible, culturally relevant wholistic mental health services for First Nations Peoples;

- establish an Akwesasne satellite office(s) in Ottawa linked to CHEO and the Royal Ottawa Hospital;

- develop a culturally appropriate Aboriginal Psychological Assessment Tool.

"For First Nations peoples, health is an intricate web of balance of one's mental, emotional, spiritual and physical self," said Mike Mitchell, Grand Chief of the Mohawk Council.

"This partnership, like no other in the country, addresses the need for culturally relevant services for First Nations peoples."

The Mohawks hope the principles of the agreement can be expanded to other areas, such as education and justice.

Differences and Features

We have seen how this form of image writing arose from material production, rather than from speech. We know that, since images play a major role in the function of memory, the components of this image writing can be analyzed within a visual context. To describe the nature of this image writing, then, we should examine a synthesis of material production with the visual aspects of memory. The basic, common denominator holding between our analysis of material production and the visual components of memory is the concept of perceived contrast, of sensed variation: the 'feature'. So, our question here will be: how can we tell the difference between the features of a natural object (for instance, a common, unmodified stone) and the features common to this form of image writing?

The easiest and obvious answer to this question is that, the features of image writing will look like things we can identify; and the features of natural, unaltered stones will not. Some will protest, however, that we can as easily interpret images in natural, random patterns (such as clouds, smoke plumes from active volcanos, wood grain, or the grain patterns of stone) as we can within examples of this form of writing. This is very true: indeed, that is how this form of writing began so very, very long ago; and, how it continued to evolve with the people who reached that ancient place of ice and volcanic fire where it reached its highest form of development. And although we will not find car parts or cutlery integrated into this form of image writing (although the random assemblage of any form of patterning will suffice as a starting point in approaching this form of writing), we can also not expect to easily identify types of dangerous sub-tropical animals that have been extinct for ten thousand years.

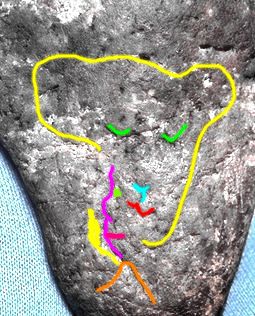

One of my very favorite

images, this composite assemblage occurs on an obverse side of a stone which shows the intelligent species of reptile (which we'll look at next); but THIS image shows (above; and in detail, to the left) a wonderful image of a sleeping North American lion - eyes shut, mouth shaped into a contented little grin - located as an image centered in the top photograph. Such lions were totemisticly associated with those who were responsible for navigating across new territory, and for making (event) maps of territory. To the lower left of the lion's face, and facing left, is the face of a child (to and for whom sweet and safe dreams are wished); and directly in from of the child's face is the face of the child's mother (a line drawn from the child's eye to the child's nose will continue on to the mother's eye and the mother's nose)...formed from the smoke plume of a volcano, much as dreams are formed as of clouds - and this volcano can be seen centered toward the bottom of the photograph on the left.

It took me until the winter of 1997-98 to find this particular piece; it was really difficult to locate. No one else, apart from myself, would have looked at the aspect of this stone which I am presenting here until 2001...no one, that is, for thousands of years because this example of non-metrical image composition may well pre-date the last ice age. First posted on the internet during the first week of September, 2001.

[Here's an observation that may be of interest to some: it seems to me, which is to say it appears to my eye, that the system of writing known as Nordic Runes could quite possibly be derived from, and based upon, a far earlier system of notation which was used for navigation; and which was composed of symbolic presentations of shoreline/coastline features (river mouths - active and dry - and delta patterns; beaches; headlands; mountains; etc.), as they would appear to someone on a vessel at sea (or, navigating along a river). If this is so, then it would be another, independent example of a relationship between a geophilosophy and a system of writing. Just a thought]!

As it turns out, the key to a successful approach in identifying and interpreting this form of image writing is difference, not identity.

What we can do here is to make use of a very basic distinction between the type of features found in natural objects, and the type of features found within the products of memory.

The features found in natural objects are always metrical in nature. They show differences that can be measured on a simple, linear scale: length, width, depth, density, concentration. volume, etc. Any divisions made within the extension of such a metrical feature will result in more of the same types of features being produced: cutting a line into parts produces more lines, dividing a depth into levels produces different depths. These features show metrical properties that are characteristic of space.

The features found in the products of memory are non-metrical in nature. They show differences between kinds of things; differences that can only be experienced within the context of time, and of a lived history. When divisions are made in the features of memory, they result in the production of new kinds of features that are different than those with which we started: the memory of a hunt, divided into parts, becomes memories of the animal hunted; the weapon used; the sense of anticipation in the chase; the feeling of joy in success. The memory of a return home, divided into parts, becomes the fire pit as first seen from a distance, the lodge in which one's family resides, the happiness on the faces of family members. These features show properties that are characteristic of time. They exhibit a definite complexity of combination, a valence of assemblage between kinds of things that produces an intricate texture of composition which always exceeds that found in natural, random, metrical patterns of grouping. Such distinctions can only be produced through memory: the memory of lived experience.

So, we can say that we are characteristicly dealing with a form of non-metrical image writing here. The only question left for us to answer is, "Who's 'time' are we looking at when we do?" And since material production, as a human activity, is ALWAYS historical, we can decide this with a very simple comparison between the experiential consistency of events from our own lives, and the experiential consistencies presented as the events of the lives of people very long ago. This is an easy determination to make, because our very sense of a 'lived present' is a direct result of the basic, mechanical repetition of our mind's perceptual input...an input that is always initially experienced as the differences of sensory contrasts. This is a constant for all human minds, now or whenever; we should thus have relatively little difficulty determining the differences between our 'lived present', and that of someone long ago (who had different perceptual inputs).

IN SUMMARY:

We can say that this type of image writing functions as a form of material production within a visual context; and exhibits those non-metrical grouping patterns which characterize the assemblage of perceptual sensory contrasts within the memory-based features found upon the event horizon(s) of those singularities which are produced through the consciousness of humans.

As with any activity taking place relative to event horizons, indeterminacy is an integral part of this image writing. Here, we are never dealing with one story 'line': there are always multiple narratives occurring, and no single interpretation ever tells the whole story. Thus, the essential texture of this form of writing can only be approached in a truly democratic fashion, with an interactive discussion being held between different readings...and with an assemblage of differences, a composition of discourses, being produced.

This is characteristic of the intersubjectivity of any language, and of any form of writing. This form of non-metrical image writing presents a level of literacy developed over tens of thousands of years; and it is a degree of literacy that far exceeds anything which phonetically based forms of writing have yet achieved. The intricacy of the linguistic textures used by the First Nations of North America almost defy any attempt to describe them in English: the compositions found within this form of writing are on the scale of a poetics in which every letter of every word is meaningfully connected with every other letter, and with the surrounding environments which it describes the events of.

Non-metrical image writing presents us with the genius of a written language which expresses the interconnectivity of the world at an experiential level, in a way that can be directly seen and intimately grasped. It is truly one of humanity's greatest accomplishments; and modern works of literature produced within phoneticly based systems of writing pale in comparison with the peak examples of this form of image writing.

Still, non-metrical image writing continues to be ignored here in Canada due to prejudicial stereotypes (which assert that the members of the First Nations were illiterate before Europeans arrived in North America), racist arrogance (which assumes that anything outside of Eurocentric, academic definitions of science must be invalid), and the ethical bankruptcy of Canada's cultural institutions (which, being heavily funded by the federal government, function in accordance with their perceived fiscal interests rather than considerations of scientific inquiry and the unconcealment of truth).

I would thus like to take this opportunity to thank the many musicians, artists, philosophers and scientists from outside Canada who have taken an interest in my research and have, in one way or another, offered encouragement...particularly those whom I have contacted directly (and their friends); and those who have responded within the context of the research I have been conducting.

"Here we have made use of everything that came within range, what was closest as well as farthest away. We have assigned clever pseudonyms to prevent recognition. Why have we kept our own names? Out of habit, purely out of habit. To make ourselves unrecognizable in turn. To render imperceptible, not ourselves, but what makes us act, feel, and think. Also because it's nice to talk like everybody else, to say the sun rises, when everybody knows it's only a manner of speaking. To reach, not the point where one no longer says I, but the point where it is no longer of any importance whether one says I. We are no longer ourselves. Each will know his own. We have been aided, inspired, multiplied."

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, page 3 ('Introduction: Rhizome'); 1987, University of Minnesota Press.

Now, all those who wander across and into this research, please remember that funding for this project is an ongoing issue; and that we all have the RIGHT to be paid for the work which we produce, and the uses to which that work is put.

THANK YOU ALL VERY MUCH AGAIN FOR YOUR INTEREST

A RECENT ADDENDUM

Those who are interested in the history of non-metrical image writing might find a recent article, published in the December 2001 issue of Scientific American, informative:

"How We Became Human: The acquisition of language and the capacity for symbolic art may lie at the very heart of he extraordinary cognitive abilities that set us apart from the rest of creation"; by Ian Tattersall.

"...Instead of some anatomical innovation, perhaps we should be seeking some kind of cultural stimulus to our extraordinary cognition. If the modern human brain, with all its potential capacities, had been born along with modern human skull structure at some time around 150,000 to 100,000 years ago, it could have persisted for a substantial amount of time as expatiation (a name for characteristics that arise in one context before being exploited in another), even as the neural mass continued to perform in the old ways...

"...Further, if at some point, say around 70,000 to 60,000 years ago, a cultural innovation occurred in one human population or another that activated a potential for symbolic cognitive processes that had resided in the human brain all along, we can readily explain the rapid spread of symbolic behaviors by a simple mechanism of cultural diffusion. It is much more convincing (and certainly more pleasant) to claim that the new form of behavioral expression spread rapidly among populations that already possessed the potential to absorb it, than it is to contemplate the alternative that the worldwide distribution of the unique human capacity came about through a process of wholesale population replacement."

The symbolic process being referred to here is our human ability to communicate through spoken languages; however, an interesting possibility suggests itself here with reference to non-metrical image writing:

"...How, other than through the use of language, could such remarkable (tool making) skills be passed down over the generations? Well, not long ago a group of Japanese researchers made a preliminary stab at addressing this problem. They divided a group of undergraduates in two and taught one half how to make a typical Neanderthal stone tool by using elaborate verbal explanations along with practical demonstrations. The other half they taught by silent example alone. One thing this experiment dramatically revealed was just how tough it is to make stone tools; some of the undergraduates never became proficient. But more remarkable still was that the two groups showed essentially no difference either in the speed at which they acquired toolmaking skills or in the efficiency with which they did so. Apparently learning by silent example is just fine for passing along even sophisticated stone tool-making techniques."

It is impossible to say yet just where and when non-metrical image writing arose; but, it did arise as an extension of stone tool-making. Thus, it is even conceivable that non-metrical image writing may, in its complexity, pre-date the complexity of spoken languages: non-metrical image writing may even be the skill through which humans developed a capacity for spoken languages!

That would certainly explain why non-metrical image writing, in its complexity, tends to leave those reading it 'at a loss for words' for describing what they are seeing so depicted.