CHAPTER

FOUR

BEGINNING OF THE END

In the summer of 1795, William Henry Harrison was present when General 'Mad' Anthony Wayne negotiated the Treaty of Greenville with the tribes inhabiting the Northwest Territory. This experience would later prepare and aid Harrison in the near future, for his training included the responsibility of seeing that the provisions in the treaty were carried out.

William Henry Harrison

(1804)

Early in 1800, Delegate Harrison, of the Northwest Territory, arose in Congress Hall to introduce a bill which proposed that Congress divide the Territory into separate political units--the Indiana Territory and the Northwest Territory. This bill was ratified, and a few weeks later President John Adams signed it, thus creating the Indiana territory.

The President choose the bill's sponsor as the first governor of the newly created Territory who was then only twenty-seven years old. Harrison had served in the regular army under the command of General Wayne and upon resigning his commission he went on to become the Secretary of the Northwest Territory in July, 1798. It was from this post that the voters of the territory elected and sent him on to Congress.

As

Governor, he was required to keep a close eye on the activities of traders and

proclivities of the Indians, and also deal with the constant spread of white

settlements on Indian tribal lands. It

took the wisdom of Solomon to deal justly with all three areas of

responsibilities and the friction they produced. Upon arriving at his new capital, Post Vincennes, he immediately

took up the reigns of leadership over a vast domain of some 265,878 square

miles that comprised the Indiana Territory.

The region held an estimated population of about 6,000 settlers, most of

them half-breeds, and many thousand of Indians (though

not included in the 1800 Census).

The

young Governor proposed to the Secretary of War, in 1802, that he begin

negotiating with the tribes in the Indiana Territory in an effort to draw up

permanent boundaries. Indian Nations to

be involved in the negotiations would include the Sac and Fox, Kickapoo,

Kaskaskia, Wea, Miami, Potawatomi and the Eel River tribes. He also proposed to the Secretary that the

Sacs be included in the Treaty of Greenville and as an inducement that $500.00

be granted to that tribe.

The lack of a treaty-defined relationship was a bone of contention between the Sac and Fox Nation and the United States. The Sac tended to ignore the Treaty of Greenville until it would place them on a equal footing with the other tribes. The rumors that were circulating about Sac holding captives also lent urgency in drawing up a treaty between this particular tribe and the United States.

It was during this period that President Jefferson purchased the vast Louisiana Territory which also embraced the Sac and Fox hunting grounds. In February, 1803, Governor Harrison received detailed instructions from Thomas Jefferson regarding the position he was to take in Indian affairs of the Indiana Territory.

The President was interested in keeping a friendly footing with all the Indian nations, and it was politically expedient, as long as the tribes held great tracts of fertile lands for which the settler-voters hungered. The government-run trading houses for the benefit of the Redman served as a means of separating the Indians from their tribal lands that might be more profitably managed by white settlers. Jefferson advocated the policy of encouraging important individuals of the various tribes to run up a sizeable debt as a means of speeding up the land transfer from the tribe to the government to pay off the debt.

The

frontier settlers were becoming increasingly alarmed, with ample justification,

by the established practice of the Sac and Fox tribesmen of visiting English

posts. During the American Revolution

this confederacy had aided the British against the colonies and the friendly

relationship had continued. The tribe

by its repeated visits in 1798, 1799 and 1803 merely wished to show goodwill

and continued fidelity to its English friends.

It was these visits coupled with other incidents that stirred suspicions

of the settlers, constantly reminding them of the hold the British had over the

Sac and Fox by their traders operating out of Canada.

About

this time the Lewis and Clark Expedition was being organized and stands,

incomparably, as our Nation's epic in documented exploration of the American

West. In 1804-06, it carried the

destiny as well as the flag of our young Nation westward from the Mississippi

across thousands of miles of mostly unknown land to the Pacific Ocean. This epic feat fired the imagination of the

American people and made them feel the full sweep of the continent on which

they lived. In its scope and achievements, the Expedition towers among the

major explorations of the world.

In

1803, the United States, while attempting to purchase New Orleans from France,

was unexpectedly sold the entire territory called Louisiana. This enormous, 838,000-square mile area

doubled the size of our national domain.

It included most of the lands drained by the western tributaries of the

Mississippi River, from the Gulf of Mexico to present Canada, and west to the

Continental Divide.

Although

Thomas Jefferson had previously proposed expeditions of western exploration,

the purchase of Louisiana now provided the impetus to move forward and Congress

authorized the Expedition. A primary

objective was to find a practical transportation link between the Louisiana

Territory and the ''Oregon Country",

claimed by the U.S. following discovery of the mouth of the Columbia River by

Captain Robert Gray in 1792.

However,

the Expedition was conceived as more than geographic exploration. Jefferson wanted information on the

resources and inhabitants of the new territory. The party was to scientifically observe and, if practicable,

collect plant, animal, and mineral specimens; record weather data; study native

cultures; conduct diplomatic councils with the tribes; map geographic features "of a permanent kind" along

their route; and record all important observations and events through daily

journal entries.

Assigning

high priority to the quest for knowledge, Lewis and Clark meticulously recorded

observations about the characteristics, inhabitants, and resources of the country

through which they passed. Not many

explorers in the history of the world have provided such exhaustive and

accurate information on the regions they probed.

Before

the Expedition, the Trans-Mississippi West was an unexplored, unmapped, virgin

land. The members of the Expedition

made their way through this vast country, living off its resources and adapting

themselves to its harsh conditions. They encountered primitive tribes and

menacing animals. On foot, on horseback,

and by boat they pushed over massive mountain ranges, across seemingly endless

plains, through dense forests, and against powerful currents of raging waters.

Meriwether

Lewis began the journey at Washington, D.C., on July 5,1803. At Pittsburgh, he gathered supplies of arms

and military stores from Harpers Ferry and Schuylkill(Philadelphia)

Arsenals. These and a wide assortment

of other items were loaded aboard a specially designed keelboat, on which Lewis

"with a party of 11 hands" departed down the Ohio River, August

30. Other men were recruited along the

way. At Clarksville, opposite

Louisville, Lewis was joined by his co-commander, William Clark. The party established its 1803-04 winter

camp along the Mississippi River, above St. Louis at Wood River(Illinois), opposite the mouth of the Missouri River.

After

a winter of diplomatic duties and final preparations, the explorers, on May

14,1804, headed their boats into the current of the river ''under a gentle

breeze." The party numbered 45 from Wood River to its 1804-05 winter

establishment at Fort Mandan(North Dakota), and

33 from Mandan to the Pacific and return in 1805-06. Lewis' Newfoundland dog, Seaman, accompanied the party throughout

its journey.

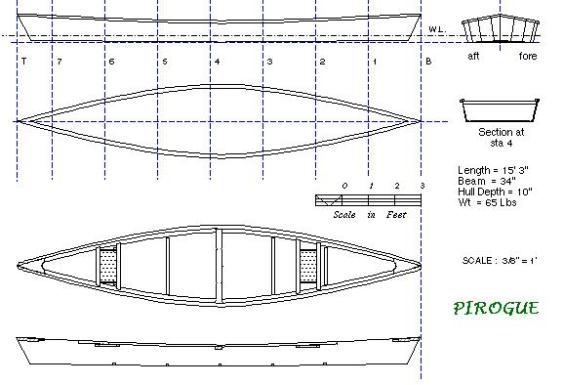

Ascending

the Missouri in 1804 proved arduous and slow as the men towed the keelboat and

two smaller more maneuverable craft, called pirogues (see page 103), against the swift current. Sergeant Charles Floyd, the only Expedition

member to die on the journey, succumbed to apparent appendicitis and was buried

near present Sioux City, Iowa. The

difficulties of the first summer and autumn forged the party into a hardened

"Corps of Discovery."

When

Captain Meriweather Lewis and William Clark were on their way to the Pacific, a message was sent to the Sac and

Fox. Not having an interpreter among

them the tribe asked a British trader to interpret the message for them. The Trader complied, but in a way

unfavorable to the US Government. When

this interpretation became known to the military authorities, Captain Amos

Stoddard(then acting governor of the District of

Louisiana) had his own interpreter re-read the message.

Replica of a Keelboat

Before Captain Stoddard could inform Dearborn of this council to rectify the false interpretation that had been given earlier, the Secretary of War authorized Governor Harrison to begin negotiations with the Sac and Fox. The Governor's invitation to parley came on the heals of the heightened hostilities between the Sac and Fox against a neighboring tribe--the Osages. The Osages were long considered the favorites of the United States. The Americans, on the other hand, did nothing to dispel this impression and the galling news to the proud Sac and Fox that a party of Osages recently left St. Louis loaded with gifts and a puffed-up sense of their own superiority finally drove a small band to direct action.

In

the early spring of 1804, there was located on the west bank of the Mississippi

River, near present-day St Louis, at the mouth of the Cuvier(French for ‘copper’) River, a settlement of white

people. Its inhabitants were mainly

French who lived chiefly by hunting, fishing and farming small patches of

land. Women in these far-flung pioneer

settlements were few and whiskey was readily available; the stage was set that

would alter Sac and Fox relations with the Americans forever. The French loved to dance and because white

women were few, readily took Indian maidens as easy and graceful dancing

partners at their social occasions. It

was at one of these dances where whiskey freely flowed that trouble began.

A

dance took place at the log cabin of one of the white settlers, several Sac

Indians were present, one of whom was a relative of the Sac Headman at

Saukenuk, Quashquamme(Jumping Fish). He had brought his daughter to the cabin,

whereupon both proceeded to have a good time.

She was enjoying the dancing while the father became intoxicated with

the whiskey. After a few hours an intoxicated

young white settler took undue liberties, which the Sac maiden resented and

left the dance floor. The now drunken

father noticed this and in a threatening manner demanded an apology. The youth grappled and overpowering him

dragged him roughly to the door of the cabin and kicked him out, as one would

an offending dog.

To

the humiliated Sac, this was an insult and wrong that in Indian culture would

justify death. On gaining his feet the

father discovered the cabin door shut so he bided his time; waited and watched

for an opportunity to present itself.

Eventually the youth opened the door and stepped out. Then out of the darkness a tomahawk split

the young man’s head open and he dropped dead at the Indian’s feet. Afterwards the father took his daughter, by

canoe, back to their lodge at Saukenuk.

About

this time, reasoning that nothing would be gained from a peaceful attitude and

that it was only fear that induced the Americans to be generous to the Osage, a

warparty of Sac attacked a few settlements on the Cuvier River, a couple of

miles north of St. Louis. The Indians made

a grievous miscalculation, for the resulting American reaction to these

incidents was not the one the tribe had expected.

Outraged

by the premeditated murder of the youth and because it was a Sac Indian who’s

identity was known that had killed a white man; and on account of the other

recent attacks on neighboring settlements, this caused the local settlers to

plan retaliatory moves against the Sac villages nearest them. Major James Bruff did manage to calm the settlers

down with promises that justice would be dispensed to the guilty parties.

In

the meantime, the marauding Sac warriors had brought the scalps of three

settlers, unrelated to the dance incident, and threw them down at the feet of

their chiefs. Fearful of reprisals and

hoping to avoid an open conflict with the Americans, two of the chiefs traveled

to St. Louis, under the protection of a French trader. The Sac chiefs freely admitted that four of

their warriors were responsible for the murders but evaded repeated requests to

surrender the individuals who committed the acts to Major Bruff.

Finally,

Bruff released the two chiefs with a harsh demand for the surrender of the

guilty Sacs. Then warning his superior

officer, General James Wilkinson, that ". . . . .there is but one opinion

here--that is--unless those murderers are demanded: given up and examples made

of them our frontier will constantly be harassed by murderers and robberies . .

. . ."

While

the inhabitants of the Missouri area were doing sentry duty, expecting a full

scale Indian war at any minute, Governor Harrison arrived in St. Louis. Upon arriving he had accepted the invitation

to stay at the mansion of a wealthy landowner and fur trader, Auguste Chouteau. Civil affairs were uppermost in the

Governor's mind at the moment and aided by Judge John Griffin, they drew up a

civil code and reorganized the courts and local militia.

The

reorganization was deemed necessary as long as the administration of the

District of Louisiana was attached to the Indiana Territory. Just as he was finishing this work a

deputation of Sac and Fox had arrived in town with one of the guilty warriors

involved in the Cuivre River killings.

Auguste Chouteau

Fur trader and founder of the city of St Louis,

MO, and represented the US Government in the negotiation of Indian treaties

when the city became part of the United States, as a result of the Louisiana

Purchase (1803)

With the surrender of the Sac, guilty of defending his daughter’s honor, Harrison was forced to take a stand on the matter. First, he considered releasing the guilty individual on the technicality that the crime has been commited under Spanish law which was now defunct. Realizing the immediate effect such a course would have on the local inhabitants and because of Maj. Bruff's objections to it, he quickly discarded this idea. Finally he decided to best handle the matter by imprisoning the Sac Indian and then applying for a pardon from the President.

The

opportunist, Harrison, broached the subject of negotiating a treaty with the

Sac delegation to extract a land cessation.

Liberally interpreting his instructions from the Secretary of War, he

dealt with both tribes as one nation, thereby, making a joint treaty possible. The Indian delegation was in a conciliatory

mood and were ready to 'wipe away the

tears' of the relatives of the slain victims—as Indian custom

demanded. The Governor showered the

group with over $2000 worth of gifts and the Indian chiefs in return were

anxious to put the raids of the Cuivre River out of their host's mind.

The

appraisal written of Major Bruff does not ring quite true about the attitudes

of the Indian delegation that eventually signed the treaty. He described them as ". . . . . willing to

make a treaty that would shelter them from their natural enemies--the Osage,

now considered by them as under the protection of the United States . . . . .

Without hesitation, offered to cede an immense tract of country containing much

valuable lead and other minerals . . . . ."

The Treaty of 1804 is considered to be at the heart of all the

conflicts that would rage off and on till the matter climaxed at the end of

Black Hawk's War in 1832. The whole

controversy hinges upon this treaty and both sides depend upon it for their

justification in all subsequent matters of dispute and misunderstandings.

For if this treaty was valid then Black Hawk and his band

were intruders, trespassers and aggressors—in 1832. On the other hand, if invalid then Black Hawk was a

patriot and hero, and the actions of our government, both national, state, and

territorial was indefensible and oppressive.

I find it appropriate

to present it here so that the reader can get a better grasp of the events as

they developed later.

TREATY OF 1804

November 3, 1804

Treaty of Saint Louis, Louisiana District with

the Sac and Fox.

Articles of a treaty, made at

Saint Louis, in the District of Louisiana, between William Henry Harrison,

Governor of the Indiana Territory and the District of Louisiana. Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the said

territory and district, and commissioner plenipotentiary of the United States,

for concluding any treaty or treaties which may be found necessary with any

northwestern tribes of Indians, of the one part; and the chiefs and head men of

the united Sac and Fox tribes of the other part.

Article

1.

The United States receive the united Sac and Fox tribes into their friendship

and protection; and the said tribes agree to consider themselves under the

protection of the United States and of no other power whatsoever.

Article

2.

The general boundary line between the lands of the United States and of the

said Indian tribes shall be as follows:

Beginning at a point on the Missouri River, opposite the mouth of the

Gasconade River: thence, in a direct course so as to strike the River Jeffreon,

at a distance of thirty miles from its mouth, and down the said Jeffreon to the

Mississippi: thence, up the Mississippi to the mouth of the Ouisconsin River,

and up the same to a point which shall be thirty-six miles, in a direct line

from the mouth of said river; thence, by a direct line to a point where the Fox

River(a branch of the Illinois) leaves the small lake called Sakaegan; thence,

down the Fox River to the Illinois River and down the same to the Mississippi. And the said tribes, for and in

consideration of the friendship and protection of the United States, which is

now extended to them, of the goods(to the value of two thousand, two hundred

and thirty-four dollars and fifty cents($2,234.50)) which are now

delivered and of the annuity hereinafter stipulated to be paid, do hereby cede

and relinquish forever, to the United States, all the lands included within the

above described boundary.

Article

3.

In consideration of the cession and relinquishment of land made in the preceding

article, the United States will deliver to the said tribes, at the town of

Saint Louis, or some other convenient place on the Mississippi, yearly and

every year, goods suited to the circumstances of the Indians, of the value of

one thousand dollars($1,000.00) (six hundred of which are intended for

the Sac, and four hundred for the Fox), reckoning that the value at the first

cost of the goods in the city or place in the United States, where they shall

be procured. And if the said tribes

shall hereafter, at an annual delivery of the goods aforesaid, desire that a

part of their annuity should be furnished in domestic animals, implements of

husbandry, and other utensils, convenient for them, the same shall at the

subsequent annual delivery, be furnished accordingly.

Article

4.

The United States will never interrupt the said tribes, in the possession of

the lands which they rightfully claim; but will on the contrary, protect them

in the quiet enjoyment of the same, against their own citizens, and against all

other white persons, who may intrude upon them. And the said tribes do hereby engage, that they will never sell

their lands, or any part thereof, to any sovereign power but the United States;

nor to the citizens or subject of any other sovereign power, nor to the

citizens of the United States.

Article

5.

Lest the friendship which is now established between the United States and the

said Indian tribes, should be interrupted by the misconduct of individuals, it

is hereby agreed, that for injuries done by individuals, no private revenge or

retaliation shall take place; but instead thereof, complaint shall be made by

the party injured to the other; by the man, said tribes, or either of them, to

the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, or one of his deputies; and by the

Superintendent, or other person appointed by the President, to the chiefs of

the said tribes.

And it shall be the duty of the

said chiefs, upon complaint being made, as aforesaid, to deliver up the person,

or persons, against whom the complaint is made, to the end that he, or they,

may be punished agreeably by the laws of the state or territory where the

offence may have been committed. And,

in like manner, if any robbery, violence or murder shall be committed on any

Indian, or Indians, belonging to the said tribes, or either of them, the person

or persons so offending, shall be tried, and if found guilty, punished, in like

manner as if the injury had been done to a white man.

And

it is further agreed, that the chiefs of the said tribes shall, to the utmost of

their power, exert themselves to recover horses, or other property which may be

stolen from any citizen or citizens of the United States by any individual or

individuals of their tribes. And the property

so recovered, shall be forthwith delivered to the Superintendent, or other

person authorized to receive it, that it may be restored to the proper

owner. And in cases where the exertions

of the chiefs shall be ineffectual in recovering the property stolen, as

aforesaid, if sufficient proof can be obtained, that such property was actually

stolen by any Indian, or Indians, belonging to the said tribes or either of

them, the United States may deduct from the annuity of the said tribes, a sum

equal to the value of the property which was stolen.

The United States hereby

guarantee to any Indian or Indians of the said tribes, a full indemnification

for any horses, or other property, which may be stolen from them, by any of

their citizens; Provided, that the property so stolen cannot be recovered, and

that sufficient proof is produced that it was actually stolen by a citizen of

the United States.

Article

6.

If any citizen of the United States, or any other white person, should form a

settlement, upon the lands which are the property of the Sac and Fox tribes,

upon complaint being made thereof, to the Superintendent, or other person

having charge of the affairs of the Indians, such intruder shall forthwith be

removed.

Article

7.

As long as the lands which are now ceded to the United States remain there

property, the Indians belonging to the said tribes shall enjoy the privilege of

living and hunting upon them.

Article

8.

As the laws of the United States regulating trade and intercourse with the Indian tribes, are already extended

to the country inhabited by the Sac and Fox, and as it is provided by those

laws, that no person shall reside as a trader, in the Indian country, without a

license under the hand and seal of the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, or

other person appointed for the purpose by the President, the said tribes do

promise and agree, that they will not suffer any trader to reside among them,

without such license, and that they will from time to time, give notice to the

Superintendent, or the agent for their tribes, of all the traders that may be in their country.

Article

9.

In order to put a stop to the abuse and impositions which are practiced upon

the said tribes, by private traders, the United States will, at a convenient

time, establish a trading house, or factory, where the individuals of the said

tribes can be supplied with goods at a more reasonable rate, than they have

been accustomed to procure them.

Article

10. In order to evince the sincerity of their friendship and

affection for the United States, and a respectful deference for their advice,

by an act which will not only be acceptable to them, but to the common Father

of all the nations of the earth, the said tribes do, hereby, promise agree that

they will put an end to the bloody war which has heretofore raged between their

tribe and the Great and Little Osages.

And for the purpose of burying the tomahawk, and renewing the friendly

intercourse between themselves and the Osages, a meeting of their respective

chiefs shall take place, at which, under the direction of the above named

commissioner, or agent of Indian Affairs residing at Saint Louis, an adjustment

of all their differences shall be made,

and peace established upon a firm and lasting basis.

Article

11. As it is probable that the government of the United States

will establish a military post at, or near the mouth of the Ouisconsin River,

and as the land on the lower side of the river may not be suitable for that

purpose, the said tribes hereby agree, that a fort may be built, either on the

upper side of the Ouisconsin, or on the right bank of the Mississippi, as the

one or other may be found most convenient; and a tract of land not exceeding

two miles square, shall be given for that purpose; and the said tribes so

further agree, that they will at all times, allow the said traders and other

persons travelling through their country, under the authority of the United

States, a free and safe passage for themselves and their property of every

description; and that for such passage, they shall at no time, and on no

account whatever, be subject to any toll or exaction.

Article

12. This treaty shall take effect and be obligatory on the

contracting parties, as soon as the same shall be ratified by the President, by

and with the advice and consent of the Senate of the United States.

In

testimony whereof, the said William Henry Harrison, and the chiefs and head

men of the Sac and Fox tribes, have hereunto set their hands and affixed their

seals. Done at Saint Louis, one

thousand, eight hundred and four, and of the Independence of the United States

the twenty-ninth.

ADDITIONAL ARTICLE

It is agreed that nothing in this

treaty contained shall affect the claim of any individual or individuals, who

may have obtained grants of land from the Spanish government, and which are not

included within the general boundary lines, laid down in this treaty: PROVIDED,

that such grants have at any time been made known to the said tribes and

recognized by them.

L.S. WILLIAM HENRY HARRISON

L.S. LAYOWVOIS, or LAIYUVA,

his X

mark

L.S. PASHEPAHO, or “The

Stabber”, his X

mark

L.S. QUASHQUAME, or “Jumping

Fish”, his X

mark

L.S. OUTCHEQUAHA, or

“Sun Fish”, his X

mark

L.S. HASHEQUARHIQUA, or

“The Bear”, his X

mark

In the presence of:

William Prince, Secretary to the Commissioner,

John Griffin, one of the Judges of the Indiana Territory,

J. Bruff, Maj. Art'y. United States,

Amos Stoddard, Capt. Corps of Artillerists.

P. Chouteau, Agent de la haute Louisiana, pour la department sauvage,

Ch. Gratiot

Auguste Chouteau

Vigo

S. Warrel, Lieut. United States Artillery

D. Delaunay

Joseph Barron sworn interpreter

H'POLITE BOLEN, his X mark sworn

interpreter

On

the 31st of December, 1804, Thomas Jefferson, 3rd President of the United

Sates, submitted this treaty to the Senate for their advice and consent and it

was by this body duly ratified.

It

was true that the Sac and Fox asked for a treaty, as early as 1802, that would

give them an annuity. They were only

familiar at that time with the English practice of giving annuities as gifts,

without a land cessation or anything else being expected it return. When Harrison received authorization to

enter into a treaty with the Sac; the Indians were notified in due course to

send some of their chiefs to Saint Louis.

It

is very probable the Sac were never aware of the large land cessation about to

be undertaken. For all practical

purposes, they came to Saint Louis with the frame of mind that the matter to be

discussed would concern the Cuivre River affair which the Americans had been

pressing them about earlier.

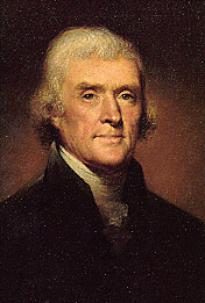

Thomas Jefferson

3rd

PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES (1801-1809)

In the following words, Black Hawk gives his

recollections of the circum-stances surrounding the Treaty of 1804.

". . . Some

moons after this young chief (Lieutenant Zebulon Pike) descended the Mississippi, one of our people killed an American. He was confined in the prison at Saint Louis

for the offense. We held a council at

our village (Saukenuk) to see what could be done

for him. It was determined that

Quash-qua-me (Jumping

Fish), Pa-she-pa-ho

(The

Stabber),

Ou-che-qua-ha (Sun

Fish), and

Ha-she-quar-hi-qua (The

Bear) should go

down to Saint Louis, see our American father, and do all they could to have our

friend released.

By paying for the person

killed, thus covering the blood and satisfying the relations of the man

murdered This being the only means with

us of saving a person who had killed another and we then thought it was the same

was with the whites. The party started

with the good wishes of the whole nation, hoping they would accomplish the

object of their mission. The relations

of the prisoner blacked their faces and fasted, hoping the Great Spirit would

take pity on them returning the husband and the father to his wife and

children.

Quash-qua-me

and party remained a long time

absent. They at length returned and

encamped a short distance below the village, but they did not come up that day,

nor did any person approach their camp.

They appeared to be dressed in fine coats and had medals. From these circumstances, we were in hopes

they had brought us good news. Early

the next morning, the council lodge was crowded-- Quash-qua-me and party came

up and gave us the following account of the mission.

On

their arrival at Saint Louis they met their American father (Harrison) and explained to him their business urging

the release of the friend. The American

chief told them he wanted land, and they agreed to give him some on the west

side of the Mississippi, and some on the Illinois side opposite the

Jeffreon. When the business was all

arranged they expected to have their friend released to come home with

them--but about the time they were ready to start, their friend was led out of

prison, who ran a short distance and was shot dead. This is all they could recollect of what was said and done. They had been drunk the greater part of the

time they were in Saint Louis.

This

is all myself or the Nation (Sac and Fox) knew of the Treaty of 1804. It

has been explained to me since. I find

by that treaty, all our country east of the Mississippi and south of the

Jeffreon was ceded to the United States for $1,000 a year! I will leave it to the people of the United

States to say, whether our Nation (Sac and Fox) was properly represented in this treaty. Or whether we received a fair compensation for the extent of the

country ceded by those four individuals.

I could say more about this treaty but I will not at this time. It has been the origin of all of our

difficulties."

The

prisoner was shot dead but not the way Black Hawk was led to believe. The pardon reached Harrison from the

Secretary of War on February 12th, 1805--too late to defuse the situation.

In the following

letter, Harrison personally explains the circumstances surrounding the lone

warrior's death.

TO: Henry Dearborn .

Vincennes 27th May 1805

Sir

The

enclosed letter from Mr. Chouteau(1) I received

this day by a Special Messenger and have returned him an answer(2) of which the enclosed is a copy.

If the Indians should now go

forward to the seat of Government (Washington) I will dispatch them a quickly as possible---on their arrival at this

place I will have them inoculated with the vaccine disease that they may avoid

the smallpox which is at this time in Kentucky--I have directed Mr. Chouteau to

go on with them because he is better acquainted with their manners and their

wants than any other person that could be procured. A party of the Sioux of the Mississippi have lately visited St

Louis for the purpose of delivering up one of their warriors who had killed two

Canadians the servants of a trader in their country--but upon examination it appeared

that the Indian killed them in his own defense and that they were the

aggressors--He was accordingly permitted to return with his friends upon

condition of his being delivered up at any time hereafter when he should be

demanded—enclosed is a letter from a friend of mine (Benjamin Parke) on the spot which gives a particular account of the

transaction--the respect which has been

manifested toward the United States by this numerous and warlike tribe

and the favorable reception which Captains Lewis and Clark have met with from

the tribes of the Missouri augers well to our affairs in that quarter and forms

a striking contrast to the conduct of some of the more neighboring

tribes--which have been treated by our Government with the utmost tenderness

and indulgence--in my last letter I informed you that it was my intention to

set out for Fort Wayne unless the instructions I expected to receive from you

should otherwise direct--upon more mature deliberation I have been induced to

abandon my opinion of the propriety of that step—first from the probability

that my services will shortly be required here to hold a session of the

Legislature and secondly because I think it would be a sacrifice of that

dignity and authority which it is necessary to observe in all our transactions

with the Indians--we are not conscious of having done them any wrong--but as

they pretend to think otherwise they have been invited to come forward and

state their grievances--and every assurance has been given that for any injury

which may have unintentionally have been done them ample remuneration shall be

made--, as they have declined this invitation I think it would be improper for

us to discover too much solicitude to give them satisfaction lest they should

attribute that to fear which is purely the effect of justice and

benevolence--An error which the Indians above all the people in the world are

prone to imbibe--As it is very possible however that they may have been imposed

upon by false statements and misrepresentations I conceived it to be a matter

of importance to remove from their minds every false impression--to ascertain

whether the uneasiness and alarm really exists amongst them to the extent that

has been spoken of and to discover who the persons are (for that there are such

I am perfectly convinced) who excite their jealousy and feed their

discontent--For these purposes I have dispatched General (John) Gibson to the Delaware and Colonel (Francis) Vigo to the Miamis and Putawatimes upon their return

I shall be enabled to give you satisfactory information on every subject

connected with their mission--

In the course of this spring

I have seen all the Chiefs of the Weas one excepted--A large deputation from

the Kickapoos of the Prairie another from those of the Vermilion River, Almost

the whole band of Eel River Indians and the only Chief of the Delaware who was

not present at the late Treaty with that tribe in none of these have I

discovered the smallest signs of discontent and I am persuaded that if it does

exist it exists no where but in the immediate neighborhood of Fort Wayne and

the Indians there are no more affected by the Treaties with the Delores and

Plankishaws than the Mandans of the Missouri.

I received by express from

St Louis a long letter from Captain Clark,

the companion of Captain Lewis--The dispatches for the President (Thomas Jefferson) and for your department were not sent on which will delay their

arrival at Washington nearly a fortnight--They passed the winter with the

Mandans 1609 miles up the Missouri in Latd. 47 º21'47" North Longte. 101 º 25' and had met with no material accident—

Your letter of the 12th Feby (February) covering the President’s

pardon of the Sac Indian confined at St Louis did not reach me until near two

months after its date--it was immediately forwarded to St Louis--but

unfortunately it did not arrive until the Indian had effected his escape from

the guard house--he was fired on by the sentinel and the body of an Indian has

lately been found near St Louis with the mark of a buck shot in his head which

is supposed to be the prisoner

I have the Honor to be with the greatest Respect and

Consideration

Sir,

your Humble Servant

Willm

Henry Harrison .

1. Letter from Pierre Chouteau that was forwarded to

Dearborn from Harrison.

FROM PIERRE CHOUTEAU St Louis, May 22nd, 1805

Mr. Wm. Hy Harrison Governor & c

Sir:

The

barge of Captain(Meriwether) Lewis arrived the day before yesterday he has sent

by this opportunity Fourty five chiefs or consideres(were 'the principal men, below the great chiefs,

of an Indian tribe' definition taken from John

McDermott's, A Glossary of

Mississippi Valley French, 1673-1850 St Louis: Washington University

Studies, 1941, p 55) of the Nations Ricaras, poncas, Sioux of the tribes on the missoury (Missouri River), mahas, ottos and Missourys in order that they may

be conducted from here to the federal city (Washington City), I send you an express to give you notice of their

arrival. They unanimously wish to

undertake this journey, but as my instructions, Whereof you have perfect

Knowledge do not permit the departure of any Indian for the Seat of government

without a Special permission, I think it is my duty to Wait your answer, before

I give them mine, and hope that in the Shortest time possible you Will transmit

to me your orders and Will direct my conduct on this occasion as minutely

as possible.

I Will observe to you that I

am ever in the Same opinion that the Warm Season is very dangerous for these

Indians, of Whom perhaps a great number Will fall Victims to So Long and

penible (i.e.,

painful) journey in a

climate so different from their own, and the

nations Should be certainly Dissatisfied and Would have a defavorable (i.e., unfavorable) idea of the government if the Indians now here

don't come back Safely amongst them. I

think that the autumn and Winter are the only proper season to undertake With

Security that trip. If you Were of the

same opinion it Would be convenient, I Believe, that these Indians Stay here or

not far from here in going from time to time to hunt in the neighboorood (i.e., neighborhood), What ever may be your opinion for the time of the

departure I think that it Will be necessary to call for Some chiefs of the

Sakias (Sac) and Foxes Who are called by

the government Which is already known to them, and also for Some chiefs of the

Sioux of the river des moens (i.e., DesMoines) Who are come here With Mr. (Lewis) Crawford and have asked for the Same journey, I promised to make them

Know the intentions of the government about it. As the expenses of the voyage Will be in proportion to the number

of the Indians Which Will amount to Sixty at least perhaps you Will find it

convenient to Send back to their nations Some of them to bring the news of the

departure of the others. Finally I Pray

you to give me Very particular instructions on every article, being desirous

that my conduct may be approved. Fix,

if you please, the certain epoch of the

departure, the number of the Indians to be conducted, if Some of them agree to go back, fix the road to be taken and

authorize me to expend Which Sums you Will judge necessary.

I Shall ever be ready to

Start With the Indians in all time and if I propose you Some objections on the

season it is only to avoid any reproach from the government or from the Indians

in the Supposition that Some unhappy event should arrive.

The party of Sioux Conducted

here by Mr. Dixon (Robert

Dickson) have Started

this morning Satisfied of the presents Which I have given them. As the Contractor is in the impossibility to

furnish me With the provisions Dayly Wanted, I Will be obliged to buy them and

I Believe that it Will be for his own account.

Mr. (William) Ewing, an interpreter, and

another man Wanted by him Will start in a few days for the Sakias.

I remain

with greatest consideration

Sir

Your humble and obed Servt

Pierre Chouteau

Agent

ADDRESSED: His

Excellency / Wm Hy Harrisson / Governor of the Indiana Territory and / District

of Louisiana / Post Vincennes.

©

© © © ©

2. Harrison's reply to Pierre Chouteau a copy that was forwarded to Dearborn.

TO: PIERRE CHOUTEAU .

Vincennes, May 27th,

1805

Sir.

I have this moment received your favor of the 22nd

instant The arrival of the Indians from the upper parts of the Missouri at this

Particular time is certainly an unfortunate circumstance After as full a consideration of the affair

as the time will allow I have determined as follows--You will please state to

the Indians the inconveniences that will attend their going on at present and

explain to them your arrangement (sic) for their spending the Summer in the Neighbourhood

of St. Louis--If they should readily agree to it that plan will be adopted If on the contrary they should express a

wish to go on you will proceed immediately to make the necessary arrangements

and set out for this place with all the expedition in your power--expedition is

the more necessary as the President (Thomas Jefferson) and the Heads of Departments will be absent from the Seat of

Government (Washington

City) after the

month of June--It is impossible for me at this distance to prescribe to you in

detail the arrangements necessary for your outfit in this Trip I must therefore leave it entirely to

yourself relying upon your Judgement and Economy that no expenses will be gone

into but such as the due execution of the object requires--I therefore hereby

authorize you to draw upon the Secretary of War (Henry Dearborn) for such Sums as may be required for the purchase

of Horses and other necessaries for the Trip,

On your arrival at this place you will receive more particular

instructions--If any engagement for interpreters has been made and no

particular objection can be made to their integrity or Capacity you will please

to employ them--An English interpreter will also be necessary--You will also

please to apply to Major (James) Bruff for an escort as far as this place when you will be furnished

with One to take you to the Ohio--I wish very much to send on a few of the

Sioux of the Demoin (DesMoines

River), and some of

Sacs and Foxes, and if you can get them ready to go on with the others do so--Every

exertion in your power must be made to deminish (diminish) the Number by sending back as many of those that

have down the Missouri as you Can get to go back--give them a few Articles that

will be acceptable and send them with a speech to their nations informing them

of the departure of their Friends for the seat of Government.

I

am very Respectfully

Your Humble Servant

William henry Harrison .

General James Wilkinson

The

explanation of that incident to the Sac delegation was assigned to the newly

appointed Governor of the Louisiana Territory, General James Wilkinson. Very shortly after his arrival from

Kaskaskia he was surrounded by a group of about 150 Sac and Fox representatives. In council he explained the situation to the

gathering by craftily telling them the late arrival of the pardon as a

manifestation of the ". . .will of the Great Spirit that he

should suffer for the spilling of blood on his white brethren, without

provocation. . ." Upon

learning the younger brother of the slain Sac warrior was present at the

council, he admonished the youth to ". . . receive and carefully preserve

it(pardon) in remembrance of his brother

and as a warning against bad deeds. . ."

Before

the Indian party departed for Saukenuk, there surfaced feelings of discontent

and regret over the treaty recently signed.

The Indians had always considered themselves as custodians of the land

and therefore possibly never realized the extent they were ceding to the United

States. Not having ever ceded land

before, they were ignorant of the land's value. In any case, The chief and three warriors deputized by the

council to ‘wipe away the tears’ of

the relatives of the slain settlers, were unauthorized to cede the vast tracts

of any lands that were specified in the treaty.

The

Indians now acknowledged they had made a bad bargain but now they permitted it

to stand. Their pride would not allow

them to take back what they had already given--their word.

An

Indian spokesman for the group representing the combined tribes addressed

General Wilkinson in a spirit of humility saying, "We hope our Great Father will consider our

situation for we are very poor, and that he will allow us something in

addition, to what our Governor Harrison had promised us". Thus Wilkinson

advocated to the Secretary of War an adjustment favoring the entire Sac and Fox

Nation, in order to secure their confidence.

The

United States was standing on shaky ground in the circumstances under which

this particular treaty was drawn up.

Historical researchers today on Indian affairs are in general agreement(on this point at least) that the United States

government in its negotiations with Indian delegations did not make it a

practice of investigating the individuals to determine how far the chiefs were

authorized to act by their own people, especially when the terms were favorable

to the interests of the United States.

Governor

Harrison was particularly careful to include in the 1804 Treaty a provision

entailing the cessation of hostilities between the Osage and the Sac and Fox

nations(Article 10). This did not go over well with the Sac since they were more

interested in canceling out the advantage their hated enemies might enjoy

rather than in having peaceful relations with them. To ensure peace in the upper Mississippi region, a fort was to be

erected at Prairie du Chien. Harrison

also protected the property holdings of his host, Auguste Chouteau, so that his

titles would not be invalidated by the land cessation.

In

the next three decades, winds of discord and distrust would swirl around the foundations

of the Treaty of 1804. Wise leaders on

both sides might try to establish mutual peaceful co-existence--but by 1832 the

bloody encounters, burnt settlements and leveled Indian villages would attest

to their failures.

General

Wilkinson, back in St. Louis, was probably the greatest villain in Early

American History. Before his appointment as Governor of Louisiana, he'd been

Commanding General of the United States Army.

Ambitious and politically-connected in the Original States, he was also very well-received by the Spanish in

Santa Fe.

In addition to his overtly treasonous communications with

the Spanish, Wilkinson was also plotting to create his own commercial and

political empire in the west. Pikes'

expeditions were sent out, partly as official American policy and partly as

Wilkinson's private espionage missions.

Playing the field, Wilkinson both helped

and hindered his partner in the imperial scheme, Aaron Burr. The General eventually testified against Burr in court, and walked away clean. Burr was acquitted too, surprisingly, in 1807, by Chief Justice John Marshall, in the United States Circuit Court of Richmond, Virginia.

Wilkinson

went on to further unglory in the War of 1812, mishandling the campaign against

the English operating from Montreal.

After marching around aimlessly, the troops went into winter quarters

and the Lakes Erie-Chaplain frontier was left wide open to British and Indian

attacks. One successful major-general

under his command, future President William Henry Harrison, angrily resigned in

protest at the complete unraveling of his

victory over Tecumseh and the British in October, 1812.

It

was enterprising young officers who were to fight and win that war in 1812.

Harrison, Oliver Hazard Perry, Winfield Scott and Zebulon Pike led their men to

victory in spite of their leaders and the politicians in Washington. In fact, another future President, Andrew

Jackson, was purposely kept out of the field and ordered to return home in

early 1813 by Wilkinson, who feared a successful rival. Harrison's resignation allowed Jackson to

take command of the Military District that included New Orleans. Jackson's career-boosting battle there took

place after the Treaty of Ghent was signed.

Guilty

by association with the General, Pike was suspected in the scandals as

well. Soon cleared, he was able to stay

in the Army, but how deeply he may have been involved is not known. Pike originally met Wilkinson as early as

1794 when both served under General Anthony Wayne in Ohio. By 1799, Wilkinson was plotting with Burr in

a series of secret meetings in New York.

Pike's

notebooks had been confiscated by the Spanish on a later expedition (1807) when

he strayed into Spanish Territory, but were returned to the U.S. in 1910. These

notes deal only with that expedition, in which Pike's Peak in Colorado which

was first noted by him and today bears his name, and are no help in determining

Pike's knowledge or involvement with Wilkinson's schemes. Pike mentions the

Spanish in a letter to Wilkinson he wrote on his return, "Governor Herrara said

that the maliciousness of the world was such as to forbid his writing, but

begged to be sincerely remembered to you".

Zebulon Montgomery Pike

His

journal, "Expeditions",

written from memory and a few notes hidden in his gun barrels, was published in

1810. Unfortunately, Lewis and Clark's "Journals", published at the same time, and got all the

attention. While Pike's reports are

invaluable, his literary style and syntax were confusing at times and the modern

reader is left guessing where the subject went. The "Journals"

are a lot easier to read.

Pike

led no more expeditions but rose quickly to the rank of Brigadier-General. During the War of 1812, he commanded the

15th United States Infantry. At the

Battle of York(Toronto, Canada) he personally led them in an heroic attack,

successfully forcing the British from their positions. As they fled, the defenders lit off the

powder magazines. 40-some Americans, including Zebulon Montgomery Pike, were

killed in the resulting explosions. He

was 34 years old.

The Upper Mississippi

River Expedition of 1805-1806

Young Lieutenant Pike commanded a party of 20 men from the First Regiment of the United States Infantry and left St. Louis on September 9, 1805. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 made most of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers' drainage areas the property of the United States. William Clark and Meriwether Lewis were already out on the Northern Plains by now, on their epic adventure. Pike had the same sort of basic exploratory mission, with an edge. His objectives were to reconnoiter British fur trade operations, establish a military post north of St Louis, and develop treaty relations with tribal leaders. The forts were needed to control potential enemies from outside and the growing trade, from inside.

Pike's

expedition of discovery was commissioned in May of 1805 by Governor James

Wilkinson, now of the newly created Louisiana Territory, whose motives were

mixed, at best. It seems that Wilkinson

actually talked Jefferson into letting him, Wilkinson, plan and order the

mission. The trip was delayed and

suffered from the effects of exposure but the group's notes and journals were

considered valuable descriptions of the geography, the Native Americans and the

variety of traders.

Most

of the early expeditions to the west and north left from St. Louis because it

was centrally located and had a large support structure. Already an established center of the fur

trade, it had a growing civilian population and a military presence at Fort

Bellefontaine, just north of town. St.

Louis also had a tradition of river navigation and there were plenty of

potential guides available. Many of

these guides and interpreters achieved fame for their skill, courage and personalities.

At

the mouth of the Des Moines River, he was met by William Ewing, then an

instructor of agriculture among the Indians, and along with him was an

interpreter and 19 Sac to assist Pike's party in navigating the rapids. In accordance with his instructions, Pike

held a council with the Sac, distributing the usual gifts and liquor with

explaining the nature of his journey among them. The promise came up in council about the factory among the Indian

Nation, as specified in the Treaty of 1804.

The chiefs indicated that they could not speak for the entire Sac Nation

but did provide Pike with a Sac messenger to explain his mission to the other

Sac villages along his route.

It

was not until the party passed the Rock River that they intercepted the first

Fox village. The inhabitants were

friendly and impressed Pike with their behavior while supplying provisions for

his party.

Prairie

du Chien, 400 miles up the

river from St. Louis, was the edge of the frontier then. An active trading

center, Prairie of the Dog was settled in 1781 on the east side of the

Mississippi. In early September Pike scouted a bluff a few miles south of

Prairie du Chien, on the west side of the River, 500 feet straight up. Pike

recommended this spot as a potential site for a fort, but an Army garrison here

would have been very difficult to supply and extremely easy for an adversary to

isolate.

The

recommendation was considered, but Fort Crawford was eventually built down on

the Prairie in 1816. The Prairie du

Chien region was covered with the mysterious landscaping of the previous

inhabitants. The 'mounds' were aboriginal, but the local Dog band of

the Fox Nation had no traditions about them.

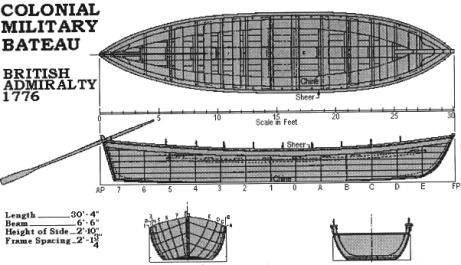

Pike substituted the keelboat at Prairie du Chien for several bateau or batteaux, as they were sometimes called.

These versatile watercraft were easier

to handle than the keelboat but were harder to keep watertight. The

party paddled up the River, past the mounds and Dakota villages, under the bluffs

and through the backwaters. It was getting colder and the steep bluffs along

the Upper River were capped by undulating prairie. The equally steep ravines

and soggy bottomlands made safe land travel along the Mississippi a very real

problem. Trails developed across the tops of the bluffs, following bison paths

and trade routes. Traders and others

used the ravines and coulees to reach the landings and settlements.

Bateau

On

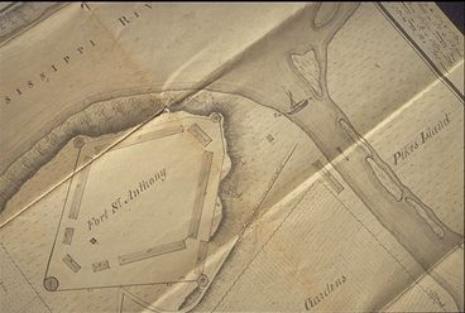

an island where the Mississippi meets the Minnesota River, Pike signed his

treaty. In 1805, the Minnesota River was known as St. Peter's River. The French trading post on the north end of

Lake Pepin back in the mid-1700s was known as, Fort Beauharnois; and it was

finally abandoned after the Treaty of Paris in 1763 gave the area to the

British.

Actually,

France cut a secret deal in 1762 and ceded its' possessions west of the Mississippi River to the Spanish, but now

it was officially the property of the United States and Pike was there to prove

it. On September 23, 1805, he bought

155,520 acres of Upper Mississippi land and water for $200 worth of presents

and 60 gallons of whiskey, on the spot, and a further promise of $2000

later. It breaks roughly breaks down to

about a dollar and a quarter an acre. Pike's treaty was a little more costly than Jefferson's Louisiana Purchase,

which worked out to 14 cents an acre. The government finally paid off on the

treaty, in 1819, to traders in exchange for Indian debts and as incentives for

further treaty signings. Signing for

the Dakota was Le Petit Corbeau, leader of the Kaposia village of Mdewakanton.

In

late September, Pike spent several days at the Falls of St. Anthony, portaging around the Falls, taking the

established route on the east side of the Mississippi. Most of the men were

ill; those that couldn't handle the batteaux

followed along on shore. Travel by land was considerably easier above the

Falls. The imposing bluffs were replaced by open prairies stretching endlessly

on either side of the River.

Winter

hit the expedition hard in early October near Little Falls. Pike's notes

indicate a relatively mild winter, with no temperatures recorded below 0° F.,

but that was irrelevant to men stranded on the open prairie and ice-bound

River. In mid-October the group erected

a stockade shelter south of Little Falls on the west side.

North West Company Logo

The North West Company had a post at nearby (Lower Red) Cedar lake

in the late 1700s. The site is just four miles west of present-day Aitkin. On

January 2, 1806, Pike and his men encountered a party from the Cedar lake post.

This was Pike's first

contact with British trade operations during the expedition. The meeting caused

some tense moments for both parties, as Pike's journal states:

" Jan.

2d. - Fine warm day. Discovered fresh

sign of Indians. Just as we were

encamping at night, my sentinel informed us that some Indians were coming full

speed upon our trail or track. I

ordered my men to stand by their guns carefully. They were immediately at my camp, and saluted the flag by

discharge of three pieces; when four Chipeways, one Englishman (Mr. Grant), and a Frenchman of the N.

W. Company, presented themselves. They informed us that some women, having

discovered our trail, gave the alarm, and not knowing but it was their enemies,

they had departed to make a discovery.

They had heard of us and revered our flag. Mr. Grant, the Englishman, had only arrived the day before from

Lake De Sable, from which he had marched in one day and a half. I presented the Indians with half a deer,

which they received thankfully, for they had discovered our fires some days

ago, and believing it to be the Sioux, they dared not leave their camp. They returned, but Mr. Grant remained all

night."

While

wintering over at Little Falls, Pike pushed on. He and a smaller group of men set out to the north, arriving at

Sandy Lake on January 8 and Leech Lake on February 1, 1806. He was commander of the expedition, but he

was now also the astronomer, surveyor, clerk, spy, guide and hunter. Nobody else in the party was capable of

anything more than pulling the sleds they'd built. By now, he was in pretty bad

condition himself, almost unable to walk.

This seems to have been the norm, given the appalling circumstances.

When the party arrived at Sandy Lake a month earlier, Pike was accompanied by

one man; the rest of the detachment limped in over the next five days.

Pike

spent little time exploring Leech Lake. He assumed he'd found a source of the

Mississippi and let it go at that. Pike

exchanged courteous letters with the administration of the British Northwest

Company. He reminded his hosts that

duties on goods have to be squared away at Mackinac and that American laws were

now in effect here. In addition, there

were to be no more political dealings with the tribes.

The

British agreed; reasoning correctly that the area would remain in their control

for many years. They also recognized

the dangers of withdrawing without leaving somebody in charge. So they told Pike what he wanted to

hear. The highlight of the week came on

the 10th of February, when Pike had the local Ojibwa men shoot the Union Jack

right off the post's flagpole. The flag

went right back up, of course after Pike had left the vicinity, most Ojibwa and

northern Indian tribes, and many of the Dakota, were solidly pro-British in the

coming War of 1812.

Pike scouted north to Cass Lake area and decided he'd found another source of the Mississippi. On February 16 Pike made a speech to the local Ojibwe leaders advising peace with the Dakota, less reliance on the British, prompt settlement of debts to traders and the avoidance of liquor. The same speech he delivered to the Mdewakanton back on Pike's Island on September 23rd. The difficult winter continued and caused the expedition to break off the trip and return. They left Leech Lake on February 18 and arrived in St. Louis on April 30, 1806.

An

interesting cultural exchange took place on this trip. Pike carried a pipe from the Dakota leader

Wabasha to the Ojibwe, who consecrated the event and sent Pike back with their

own pipes. A similar ceremony took

place when Pike returned on April 11, on the bluff where Fort St. Anthony(renamed later as Fort Snelling) was to be built. The smoking of the pipe sanctified a

promising new era of peace and harmony on the frontier. .

Meanwhile

President Jefferson, in order to quell the continuing disturbances between the

Osage Nation and the Sac and Fox Nation, decided that a show of force was

necessary and ordered Governor Harrison to proceed and join with

Wilkinson. Both governors dispatched

messengers to all the tribes of the upper Mississippi region to meet in council

at St. Louis and by September, 1805, the tribal representatives started

gathering from the surrounding area east and west of the Father of Waters.

Governor

Wilkinson had received reports from Pike indicating a general dissatisfaction

stemming from the 1804 treaty and the related incident of the warrior's

death. These and other reports added to

the governor's uneasiness. Reports came

also confirming the fact that the Sac had attempted to form a confederacy among

the other tribes to attack settlements; fortunately, it had never

succeeded. This fact provided little

consolation for Wilkinson, for while the Sac were participating in the council

here at St. Louis, the tribe had a warparties out against the Osage.

To

further complicate matters, the British traders were capitalizing on the Sac

and Fox discontent about their annuity payment. Unfortunately, the goods that were promised had arrived in St.

Louis in such poor condition and unsuited for the Indian's needs that both

governors decided to sell them for what they would fetch and from the proceeds

purchase more appropriate and better goods from the local St. Louis merchants.

Regardless

of the adverse conditions that both governors worked under, a treaty was ironed

out and agreed upon by all the following Indian nations attending the

council: Sac and Fox, Potwatomie,

Kaskaskia, the Sioux of the Des Moines River, Iowa, Kickapoo, Delaware, Miami,

and Osage. On October 18th, 1805, a

treaty of peace was signed for whatever the parties cared to make of it.

Reporting

to the Secretary of War, both Harrison and Wilkinson advocated a show of

military might near Prairie du Chien to check British influence and stem

possible Indian attacks. The

possibility of an Indian visit to Washington might be both timely and overawe

the Indians with visions of American strength.

This in turn, could lead to improving the relationship between the Indian Nations and the United States. As part of a program put together by President Jefferson, the Secretary of War authorized Governor Harrison to form a deputation of tribal chiefs and send them on a visit to Washington.

In October, Captain Amos Stoddard set

out for Washington with a specially selected delegation comprised from the

following tribes: Oto, Missouri, Kansas, Iowa, Pawnee, and Osage(west of the

Mississippi), along with Sac and Fox, Miami, Kickapoo, and Potawatomi

chiefs(east of the Mississippi). The

deputation was limited to 26, among whom the Sac and Fox chiefs made up a third

of the entire group.

Traveling

by horse to Louisville, Kentucky, up the Ohio River by boats and then overland

by carriage from Wheeling to Washington, they arrived at Washington around the

first of the year (1806). In the course of their Washington trip,

President Jefferson singled out the Potawatomi and the Sac and Fox

representatives with appropriate ceremony and delivered a speech to them.

During

the autumn of 1805, when the delegation was enroute to Washington, Sac

warparties were constantly leaving their villages in search of rival Osage

bands. Rather than returning to their

villages empty handed, from time to time they lifted white scalps. The Sac were accused of killing a man

working at a salt works about seventy miles above Portage des Sioux and

attacking another salt works along the Missouri River. This one was operated by the son-in-law of

the famed Daniel Boone, William Hays.

Fearing the possibility of general war, Governor Wilkinson took

immediate steps to end the incidents.

On

the 10th of December, 1805, Wilkinson assembled a deputation of Sacs warning

them of the dire consequences that would result if they continued in their

warlike conduct. In the spring of 1806,

the reports of Captain James B. Many and Lieutenant Pike indicated an

increasing hostile attitude of the Indians toward American settlers. These attitudes were attributed to the

discontent arising from the Treaty of 1804 and the growing influence and

interference of the British North West Company, who operated among the tribes.

The

officials in Washington, after the departure of the Indian deputation, were

formulating plans to strengthen the American position among the Indian Nations

living in the Mississippi River region.

Accordingly, The Secretary of War, Dearborn, appointed Nickolas Boilvin

as Indian Agent at the Sac village located at the lower rapids of the

Mississippi. A Canadian by birth and

now a resident of the Illinois frontier, he had served under Pierre Chouteau as

interpreter.

William

Ewing, the agriculturist Boilvin replaced as official agent to the Sac, was a

thoroughly despicable individual.

Governor Wilkinson, himself, called Ewing 'utterly unqualified'. Despite such observations, Ewing had somehow

managed to retain his position. It was

William Clark, now Brigadier-General of the militia of the District of

Louisiana, who enlightened the Secretary of War about this contemptible character. In a letter to Henry Dearborn, he accused

Ewing of unauthorized purchases in the name of the government, then trading the

purchased whiskey for Indian guns--later reselling the firearms back to the

warriors at considerable profit.

Pierre

Chouteau, Clark and Boilvin turned out to be excellent choices during the first

three years of official relations between the Sac and Fox Nation and the United

States. These three individuals acted

well to countercheck the growing influence of Robert Dickson, the British

trader at Prairie du Chien, in combating English intrigue among the tribes.

So

while the Sac and Fox chiefs were in Washington visiting President Jefferson;

their fellow tribesmen were scalping an occasional white settler while hunting

rival Osage bands. A new shining star

was rising in the heavens of the Red World--he was known as, Tecumseh !

Last updated on NOVEMBER 09, 2002 by J.D. Tipfer