CHAPTER

TWO

RED

WORLD

Among

the earliest narration handed down from the Indians, there is a parable that

serves to illuminate the vast cultural gulf that separated them from the

Europeans. It begins at the time of Creation when the white man was given a

stone and the red man was handed a piece of silver, despising the stone the

white man threw it away, while the red man finding the silver equally worthless

likewise discarded his piece. Later the white man pocketed the silver as a

source of material power while the red man revered the stone as a source of

scared power. This theme colors Indian and White relations to this day with but

few exceptions.

When

Christopher Columbus set foot in the Bahamas, in 1492, North America already

held a population estimated by some to have be between seven to ten million

people. These Native Americans developed several hundred distinct cultures and

spoke over two hundred separate languages. The hunting bands, tribes, nations

and confederacies were as different and distinct from each other as the nations

of the Old World. In the Midwest, their territories were covered with 'traces' (networks of narrow moccasin-worn paths) and these

trails were followed by hunters and tribes for uncounted generations.

At

first the Atlantic Coast nations were hospitable to the early settlers, who in

turn dubbed the chiefs as kings and their wives, sons and daughters as queen,

princes and princesses. It was an acknowledged Indian courtesy to extend hospitality to all non-Indian passers-by. They never

bothered to inquire whether their guests were misfits or whatever. There were

no customs that prevented intermarriage which frequently resulted in

'half-breed' offspring. 'Squaw men', slang for white men who had an Indian

wife, were always assured acceptance among the tribe when shunned by

'civilized' white society. If the half-breed offspring were ostracized from

white settlements, they always found Indian homes. Growing up in a bilingual

and bicultural atmosphere made them well suited to fill the role of frontier

interpreters and traders.

It

is almost impossible to conceive two more diverse ways of life and systems of

belief than those represented by Indian and European societies. The enormous

differences in religious values and practices, the conduct of family and social

life, concepts of property ownership and land use, and the traditional

attitudes toward leisure and work made interchanges between Indian and whites

anything but smooth.

During

the 1500's and 1600's, timber and fur-bearing animals were becoming scarce

natural resources in the Old World; Europeans started looking to the New World

for replacements. Jacques Cartier(1534) and

Henry Hudson(1609) were business agents looking

for new markets. Later everyone started competing with the Indians for

exclusive trading privileges, bribing the Redman with liquor, trinkets and

guns.

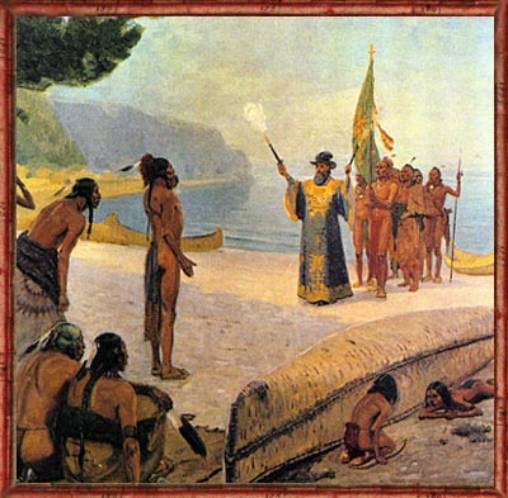

Jean Nicollet meets

the Sea People

Hoping to find the

route to Asia in the course of a long voyage which took him to Lake Superior,

Jean Nicollet made a point of bringing with him "a great robe of Chinese damask, all dotted with flowers &

birds of various colours". W. W.

Dewing, State Historical Society of Wisconsin; Aldus Books, London. (Taken from Nos Racines)

It

was in the area of collecting furs that native expertise and manpower were

essential; for the Indians possessed the skills and methods for trapping,

skinning and soft-tanning hides. Indian nations were encouraged to abandon

inter-tribal trading and devote their energies to hunting animals for the insatiable

fur markets of Europe. The Redman then began receiving a wide range of new

goods in return for his services; such as knives, hatchets, scissors, woolen

cloth, brandy(from the French), 'demon rum'(from the English), muskets, powder and shot. By the

mid-1600's, these items and others became an indispensable part of the Woodland

Indian lifestyle.

The

French did business via the rivers, while the British traded by muleback.

Toward the end of the 1700's the individual peddler-trader would be replaced by

companies that operated from a string of frontier trading posts. The Indians

would haul their prime winter pelts to these outposts in the spring or barter

with company agents travelling among them while on the move. This one factor

was primarily responsible for the vast transformation of changing patterns of

Indian life that had been virtually unchanged for centuries.

Wherever

it was they had migrated from the east, the Fox and Sac had lived in southeast

Michigan for many years before the French came to the Great Lakes, and what had

once been a peaceful region was disrupted by their fur trade. The French

reached the Huron villages at the south end of Lake Huron in 1615. After the

long and dangerous journey from Quebec, few of them were willing to go farther,

and beyond this point, most of the fur trade was conducted by the Ottawa and

Huron.

To

reach this far into the interior, the French had been forced in 1609 to win the

trust of the Algonquin and Montagnais by helping them drive the Mohawk from the

upper St. Lawrence River. Unfortunately, this also earned the French the

lasting hostility of the Iroquois, and to avoid their war parties, French

traders were forced to detour up the Ottawa River to reach the Huron. This

precaution proved adequate enough until after the British captured Quebec in

1629 preventing French trade goods from reaching their native allies and

trading partners.

In

1610 the Iroquois had started trade with the Dutch along the Hudson and, after

defeating the Mahican in 1628, dominated this trade. Taking advantage of the

interruption of French trade by the British, the Mohawk attacked the Algonquin

and Montagnais

in 1629 to reclaim the upper St. Lawrence. The next 70 years of continuous intertribal

warfare which followed are known as the Beaver Wars (1628-1700).

By the time Quebec was returned to the French in 1632, their native allies were

retreating, and the Iroquois were threatening to cut the trade route to the

Great Lakes. To restore the former balance of power, the French began supplying

firearms to their allies, but the Dutch quickly countered by selling guns to

the Iroquois.

Meanwhile,

the fur trade had exhausted the beaver in the Huron homeland as well as those of

their Ottawa, Neutrals, and Tionontati trading

partners. Needing new hunting territory, they found this in lower Michigan and,

using the firearms and steel weapons acquired from the French, attacked the

Algonquin-speaking tribes who lived there.

The

French were aware of this but, with the exception of Jean Nicollet's journey to

Green Bay (Wisconsin) to arrange peace between

the Winnebago and the Ottawa and Huron in 1634, little was done to stop it.

Exactly what happened is uncertain, since only a few scattered reports were

relayed to the French by the Huron. Besides the Fox and Sac, three other

Algonquin tribes occupied lower Michigan at the time: Mascouten, Potawatomi,

and Kickapoo.

Unfortunately,

the Huron made little distinction between them and, perhaps borrowing the

Ottawa name for the Potawatomi, usually referred to them collectively as the

Assistaeronon (Fire Nation). Located in

southeast Michigan, the Fox took the brunt of the early fighting. They defended

themselves well in the initial confrontations. In 1635 the French learned that

the Erie had abandoned some of their villages at the west end of Lake Erie

because of a war with an unknown Algonquin enemy.

This

"unknown Algonquin enemy" was most likely either the Fox or Kickapoo,

but during the next decade, the obvious advantage of European steel and

firearms over traditional weapons took its toll. Constant raids by large

combined war parties of Neutrals, Nipissing,

Ottawa, Huron, and Tionontati began dislodging the resident tribes. The

Potawatomi were the first to leave, with the first groups arriving north of

Green Bay in 1641, but the very hostile reception they received from the

Winnebago forced them north to seek refuge with the Ojibwe

near Sault Ste. Marie.

Radisson

and Des Groseilliers

Pierre Esprit Radisson

and Médard Chouart Des Groseilliers are heroes of mythical proportions in the

history of the fur trade in New France. In their lifetimes, both had their

shares of disgrace and glory. They are represented here at the entrance of Fort

Charles (Fort Rupert), the first trading post established by the Hudson Bay

Company. These two Frenchmen were instrumental in creating and implementing

this English company on the shores of Hudson Bay. Source: H.B.C. Collection

The

Fox and Sac withstood the assaults a little longer, but during 1642, 2,000

Neutral and Ottawa warriors destroyed a large fortified Mascouten village in

south-central Michigan, and resistance began to collapse. The Fox, Kickapoo,

and Mascouten retreated west around the southern end of Lake Michigan where the

Kickapoo and Mascouten finally stopped in southwest Wisconsin. The Sac

apparently went north and crossed in the vicinity of Mackinac to settle on the

upper Wisconsin River west of Green Bay.

After

some confrontations with the Illinois, the Fox located along the Fox River

between the Wisconsin River and Lake Winnebago. The reception they received from the Winnebago was just as

friendly as the one given the Potawatomi a few years earlier, but this time

fortune dealt harshly with the resident tribe.

The Winnebago organized a large war party to attack a Fox village on

Lake Winnebago, but while enroute in their canoes, it was caught on the lake by

a storm and more than 500 of their warriors were drowned. Seriously weakened by

this setback, the Winnebago collected into a single large village for defense,

ideal conditions for the devastating epidemic which struck them. Without

raising a hand against them, the Fox had the Winnebago who survived trapped

inside their fort unable to harvest their corn and starving.

At

this point, the Illinois, traditional enemies of the Winnebago, saw an

opportunity for an alliance to fight the flood of refugees descending on them

from Michigan and sent 500 warriors with food to help their old enemies. The Winnebago held a feast to honor them,

but unfortunately old hatreds and distrust prevailed. In the midst of the celebration, the Winnebago turned on their

guests and killed all of them. When the

Illinois learned what had happened to their warriors, they began a war of

extermination which almost destroyed the Winnebago. The Fox and other Michigan refugees afterwards encountered little

resistance to their relocation in Wisconsin.

Ultimately, almost 5,000 Fox settled in central Wisconsin and became one

of the most powerful tribes in the area.

Tribes

battled one another for rich trapping grounds as commercial trading agreements

between white and Indians started springing up. Like the special trading agreement that had existed between the

French and Huron. This exclusive treaty

so angered the Iroquoian Confederacy that they later joined forces with the

Dutch and English, who in turn supplied them with firearms. The alliance

contributed to the English victory in the French and Indian War and also

allowed the Iroquois to ruthlessly dominate the fur trade in the northeastern

part of the North American continent.

The

major stumbling block between the two cultures was their opposite attitudes

toward the land. Europeans on arriving

in North America, cleared forests and cultivated the ground, hunted game in

massive quantities, mined the land looking for gold or silver and began

peopling villages and towns patterned after their homelands. The Indians always considered themselves as

'custodians' rather than 'engineers' of the land.

Europeans

tended to measure the earth, like a commercial commodity, fencing it off,

tilling or building upon it with an abandon that horrified the Redman. At the same time the colonists, whose

culture was based on private ownership and personal riches, looked with disdain

at the Indian's custom of sharing the land in common. The European land-ownership concept was so alien to the Indians'

way of thought that it was incomprehensible to them. Each Indian Nation knew the boundaries of their cornfields and

hunting territories. These boundaries were

not fences around jealously-held private lands.

At

first these diverse concepts presented no difficulty when colonial presence was

limited. Moments of peaceful co-existence were possible as the early pioneers

took up squatting and hunting privileges in the Redman's territory; especially

when tribal and colonial interests overlapped--as with matters of trade. When the white populations grew, friction

developed between the two worlds.

Tribes were trying to live off the lands the settlers now coveted.

As game thinned, the white settlements pushed the Indians ever further

westward. Whatever balance that existed before between the two diverse cultures

was now shattered by racial prejudice and religious intolerance.

When

the rebellious colonies--the 'thirteen fires'--won their independence from

Britain, the United States entered this commercial war. Thanks to the Indian,

the natural resources of the North American continent enriched European and

American lives and pocketbooks. In the Midwest the toll on the Redman was high

as inter-tribal trading and commerce were shattered by the intense focus on one

commodity--furs. With the animals over-hunted and disappearing, the Indians'

prosperity was dissolving, like the morning dew under the sun.

Combined

with unscrupulous traders that plied the Redman with watered down liquor,

dealing in shoddy mass-produced goods, inflated markups on the now

indispensable survival items--all this and much more contributed to the

Indians' rapid decline.

The

main justification the settlers used for usurping tribal homelands was the

concept of 'right of discovery'. This concept was born in the early 1500's

by Spain and later used by the early explorers in claiming vast tract or

territories in the name of the monarch or commercial interest who had paid for

their ventures. The United States

Supreme Court upheld this concept in 1823 and, of course, where the 'right of discovery' would not suffice,

the use of conquest or armed takeover would.

Indian

nations were being torn asunder internally by the deteriorating relations

between themselves and the whites. There were the 'breeches'(pants-wearing) Indians who adopted white ways and the

'blankets'(traditional) Indians staying loyal to

the old way of life. Despite the forces brought to play to make the Redman

choose sides between the European powers and America, the Indian never once

considered himself as a conquered race; later yes, but not in the beginning.

They had always managed to retain a vision of an independent identity.

With

the emergence of a new nation, the United States, a ruthless Indian policy was

implemented: removal, enclosure or extermination of the 'red devils'. The

frontier pressure pushed the tribes closer together and ever farther inland. The friction generated a wildfire of tribal

wars; the white world encouraged and abetted these divisions between the Indian

tribes and within the tribal structures.

Old World wars were mirrored in North America, during 1776 and 1812, as

the sovereign powers enlisted Indian allies of either side, pitting tribe

against tribe—thus division and conquest were simultaneously accomplished.

Over

the decades since 1492, a theme is repeated over and over again; the reasoned

plea to the whites to recognize the Indian to be themselves. The English in the

mid-1700's attempted to respect and establish peaceful co-existence between

themselves and the Redman by setting aside living space for friendly tribes.

These early prototype reservations did not solve the problem and finally, in

1763, the British drew up a proclamation calling for a boundary line between 'civilization' and 'Indian Territory'--which was defined as any lands beyond the heads

or sources of any rivers which run into the Atlantic Ocean from the west or

northwest. Yet, even this separate-but-equal scheme failed.

As

tribe was pushed into tribe with the spread of the western frontier expansion,

some Indian nations were ultimately exterminated; others merged with stronger

tribes for protection; and still others managed to retain their identities

somewhat intact to the present.

As

the early Americans came to believe that it was God's Will for them to spread

from sea to shining sea--the concept of Manifest

Destiny was born. During the 1800's, the tribes gathered around the trading

posts in the spring to barter their prime pelts for goods. It was at these same

posts that they would later meet governmental representatives of the United

States to discuss terms of surrender and treaties of peace. By this time the

only thing the Indians held that

.

interested

the whites was their land, and this was often acquired without fair means of

exchange or recourse. Now, peaceful

co-existence was a dead dream and the only path the Redman could follow was as

a fugitive of a conquered nation.

The

Indian's capacity for self-survival cannot be underestimated. As the expansion

of the frontier took place, only the Indian sought to preserve their art,

poetry, religion, myths and other artistic mediums. The white world took notice

only to decry it as being pagan and primitive. When the United States Bureau of

Indian Affairs was created to urge the Redman to adopt new ways by taking up

new faiths and skills, Indian nations, on the whole, passively resisted further

erosion of their values.

Time

passed and much Indian knowledge and art was fading away forever. Then, for the

first time, the universities of the East, during the 1830's, took notice of the

vanishing traditions and gave recognition to the Redman as a people and as men.

This was also the era of the Grimm Brothers, of Hans Christian Anderson and

others who went about assembling folklore collections of the Old World. The

scholars on the Atlantic Seaboard were quick to grasp the possibility of New

World parallels for similar collections.

A

new science, anthropology, was conceived from geology by philosophy and

embraced the physical and metaphysical aspect of man. What is known of the Sac

and Fox traditions, social organization, art and myths is fragmentary at best.

It was because of men like Henry Schoolcraft, George Catlin and Washington

Irving who recorded the Indian's customs and myths by their words and drawings.

It was from such men as these that present-day scholars are indebted.

"RECORD !" became the rallying cry

of those who followed in their footsteps, fast on the trail of vanishing Native

American folklore. An analysis of all research will almost convince you that

myths and legends are repeated from tribe to tribe and changes with the local

ecology.

There

has been added to this chapter three myths: one derived from the Sac and Fox

after they confederated into one tribe, one drawn exclusively from the Sacs and

the other one from the Foxes. I have

presented them as they appeared in the original text, as tales, beautiful in

themselves and in their relationship to the lives of the original tellers.

L E G E N D S

& M Y T H S

The

mythological world of the Sac and Fox was divided by fours: the four seasons,

the four divisions of the day or life and, of course, the four world corners--the

cardinal directions(north, south, east and west). There were five basic

type-characters augmenting the myths and legends and they are: (1)the HERO, (2)the TRICKSTER, (3)the HERO-TRICKSTER(possessed traits found in the other two), (4)the GRANDMOTHER SPIDER, and lastly her

grandsons, (5)the TWIN WAR ENTITIES.

The

HERO stands for wisdom, strength and

perception of men. He is the intermediary between Nanabozho(God) and mankind, often stepping between nature and

man. In this character, he is found protecting the weak and sending visions to

youth.

The

TRICKSTER is incorporated to explain

natural phenomena, especially used to infer an occurrence from which a moral

can be drawn. This character is a cross between Eros and Pan in Greek

literature.

The

TRICKSTER-HERO closely resembles the

Prometheus concept in our mythology; sometimes doing good intentionally and

other times by accident. In the 'trickster' mode he is capable of mischief and

chaos. Found in the 'hero' mode, he can defeat death or bring gifts to the

people.

The

GRANDMOTHER SPIDER has it's analogue

in Eve. Ancient to begin with, she is capable of becoming young and beautiful

when it suits her purpose, usually living in solitude or with her grandsons

between adventures. She directs men's thought and destinies by her kindness.

The

TWIN WAR ENTITIES are the hardest to

pin down and define but through them we can perceive the duality basic to all

men. One is good the other evil and both are the personification of action--not

contemplation; virgin-born and of supernatural lineage, but basically

human--therein lies their appeal and puzzle.

R E L I G I O N

At

the core of the Sac and Fox beliefs lies the complex spirit concept: the

Creator(Nanabozho) --One and the All-in-All.

Within his guidance other supernatural beings exist--all of them great but none

of them all-powerful.

In the

confederated tribes' traditions they have an account referring to the creation

of the world, the deluge, and the re-peopling of the earth and follows: Doctor Galland's, "CHRONICALS OF THE NORTH AMERICAN SAVAGES", entitled 'The Cosmogony of the Saukee and Musquakee

Indians' the footnotes have been kept as in the original.

" In

the beginning the Gods created every living thing which was intended to have

life upon the face of the whole earth; and then formed every species of living

animal. After this the Gods also formed man, whom they perceived to be both

cruel and foolish. They then put into man the heart of the best beast they had

created; but they beheld that man still continued to be cruel and foolish.

After this it came to pass that Nanabozho took a piece of Himself, of which he

made a heart for the man; and when the man received it, he immediately became

wise above every other animal on the earth.

And

it came to pass in the process of much time, that the earth produced it's first

fruits in abundance and all the living beasts were greatly multiplied. The

earth about this time was also inhabited by an innumerable host of I-am-woi (giants) and gods. And the gods whose habitation is under

the seas, made war upon We-suk-kah (the chief god upon the Earth) and leagued themselves with the I-am-woi upon the

earth against him.

Nevertheless, they were

still afraid of We-suk-kah and his immense host of gods; therefore they called

a council upon the earth. At the council, both the I-am-woi and the gods from

under the seas, after much debate and long consultation, they resolved to make

a great feast upon the earth and to invite We-suk-kah, that they might beguile

him, and at the feast lay hands upon him and slay him.

And

when the council had appointed a delegate to visit We-suk-kah, they commanded

him to invite We-suk-kah to the great feast; which they were preparing upon the

earth for him. Behold, the younger brother of We-suk-kah was in the midst of

the council, and being confused in the whole assembly, they said unto him,

'Where is thy brother, We-suk-kah?' And he answering said unto them, 'I know

not; am I my brother's keeper?' And the council perceiving that all their

devices were known to him, they were sorely vexed. Therefore, with one accord

the whole assembly rushed violently upon him; and thus was slain the younger

brother of We-suk-kah.

Now when We-suk-kah had heard of the

death of his younger brother, he was extremely sorrowful and wept aloud, and

the gods whose habitations were above the clouds heard the voice of his

lamentations. They leagued with him to avenge the blood of his brother. At this

time the lower gods fled from the face of the earth, to their own habitations under

the seas. The I-am-woi were thus forsaken and left alone to defend themselves

against We-suk-kah and his allies.

Now

the scene of battle, where We-suk-kah and his allies fought the I-am-woi, was

in a flame of fire; and the whole race of the I-am-woi were destroyed with

great slaughter, that there was not one left upon the face of the whole

earth. When the gods under the sea knew

of the dreadful fate of their ally, the I-am-woi, whom they had deserted, they

were sore afraid and they cried aloud to Na-nam-a-keh (god of thunder) to come to their assistance. And Na-nam-a-keh heard

their cry and accepted their request and sent his subaltern, No-tah-tes-se-ah (god

of the wind) to

Pa-poan-a-tesse-ah (god of the cold) to invite him to come with all his dreadful host of

frost, snow, hail, ice and the northwind to their relief.

When this destroying army came from the

north, they smote the whole earth with frost, converting the waters of every

river, lake and sea into solid mass of ice, and covering the whole earth with

an immense sheet of snow and hail. Thus

perished all the inhabitants of the earth: men, beasts, and gods except a few

choice ones of each kind, which We-suk-kah preserved with himself upon the

earth.

And

again it came to pass in the process of a long time, that the gods under the

sea came forth again, upon the earth. When they saw We-suk-kah, that he was

almost alone on the earth they rejoiced in assurance of being able to destroy

him. But when they had exhausted every scheme, attempted every plan and

executed every effort to no effect, perceiving that all their councils and

designs were well known to We-suk-kah as soon as they were formed; they became

mad with despair. They resolved to destroy We-suk-kah by spoiling forever the

face of the earth, which they so much desired to inhabit. To this end,

therefore, they retired to their former habitations under the sea and entreated

Na-nam-a-keh to drown the whole earth with a flood.

And Na-nam-a-keh again hearkened to their cries, and

calling all the clouds to gather themselves together, they obeyed his voice and

came; and when all the clouds were assembled he commanded them and they poured

down water upon the earth. A tremendous torrent of rain fell until the whole

surface of the earth, even the tops of the highest mountains were covered with

water. But it came to pass, when We-suk-kah saw the water coming upon the

earth, he took to the air, and made an o-pes-quie (vessel) and getting into it himself, he took with him all

sorts of living beasts, and man; and when the waters rose upon the earth the

o-pes-quie was lifted up and floated upon the surface, until the tops of the

highest mountains were covered with the flood. And when the o-pes-quie had

remained for a long time upon the surface of the flood, We-suk-kah called one

of the animals, which was with him in the o-pes-quie and commanded it to go

down through the water to the earth, to bring from thence some earth. After

great efforts and with much difficulties the animal at length returned, bringing

in its mouth some earth. Of which when We-suk-kah had received it, he formed

this earth and spread it forth upon the surface of the water; and went forth

himself and all that were with him in the o-pes-quie, and occupied the dry

land."

The

Sun became their father and the Earth their mother in the Redman's religion.

Contact with the earth and exposure to the sun brought strength and blessings.

Winds, rain, clouds, thunder, etc… are a means of communication to the tribe.

The importance of moon and stars are present and all nature is regarded as

being endowed with protective powers.

The

Sac and Fox held strongly to the belief that aid from benevolent spirits could

be obtained through fasting, suffering and prayer. 'Power' was defined as the

animating force of the cosmos and comes from Nanabozho(God,

Creator) and there is no English analogue adequate to describe what this

Indian Nation meant to convey when using this term.

The

confederated tribe had no formulated or precise concept of the afterlife. Their

expression used to refer to one who had died was 'he went'. Their belief in the

soul was strong and the ghost world was said to be in the West, beyond the

setting sun, and it was here the souls go after death.

A

belief existed in both tribes, that when a person died the soul immediately

left the body. The dead member's family, within four years, had to adopt

another person of the same sex and age as the deceased as a replacement. From

this time on, the adopted member was treated as kinship, exactly the way

his/her dead counter-part would have been.

The

concept of Heaven was vague but there are clear references made concerning

unhappy souls--dissatisfied or evil persons--returning to earth to wander,

usually in the form of owls. An owl represented a messenger of the dead and was

considered as an ill omen to both of these tribes.

The following myth, derived from the Sac tribe, concerns the owl and it's role in their myths. Without exception the owl is a bird of ill omen to every major North American tribe. It is usually cast as the harbinger of death or the bearer of a message from the dead. The Sac believed that an owl could cause facial paralysis if glimpsed at night.

The owl fulfills it's threefold function in the following story. It

warns, it demands and it punishes in the following tale told to Carol K.

Rachlin by Bertha Manitowa Dowd of the Sac Tribe.

" Nina

and Joe lived about a mile from Joe's fathers. The two houses had been built

about the same time, and Joe worked both allotments, for his father was too old

to do much physical labor.

There

was a lot of visiting back and forth. The old man lived alone, so Joe's

children went over to see their grandfather almost every day. In the evening,

when the work was finished, Joe and Nina would go to the old man's house,

usually taking some food with them. He could cook, but he didn't like to, so

Nina saw to it that there was something in the house he could heat up the

following day.

Joe

and Nina never stayed out late because they didn't want the children to be in

the house too long at a time. One evening, as they were walking up the lane,

they heard a cry overhead, and an owl swooped past them diving through the

trees in the direction of Joe's fathers house.

'Something

bad will happen!' Nina cried, drawing her shawl over her head.

'Maybe

not,' Joe shakily reassured her. 'Maybe it will be all right.'

'He

went to your father's place! Something bad will happen to him!' sail Nina. 'Do

you want to go back and see?'

'No,

we'll go first thing in the morning.'

When

they got over there the next day, the old man seemed to be alright at first. He

was sitting in his chair by the table, with a cup of coffee in front of him.

When he tried to lift the cup to his lips, through, he could not control his

hands and when he tried to stand up he could not move from his chair.

Nina

hurried to the next room. 'He wants water,' she announced when she returned.

She picked up a cup and a spoon from the table. 'Come with me,' she ordered her

husband, and Joe obediently followed his wife into the next room. He stood by

his father's bedside while she let one drop of water at a time drip into the

old man's mouth. He swallowed it, little by little, and when he was satisfied,

Nina set down the cup and spoon on the chair.

'He

needs water,' she said. 'We've got to keep giving him water.' Day and night,

for four days, she stayed with her father-in-law and whenever that choked owl's

cry came, Nina dripped water into the old man's mouth. Joe came and went, for

farm work waits for neither life or death, but at the end of the fourth day he

could see that his wife was worn out.

'Go

on home,' he instructed her that evening. 'Get some rest. I'll stay with him

during the night."

'Are

you sure you can take care of him?' asked Nina.

'Sure

I'm sure, I've watched you give him water about a hundred times, I bet,' said

Joe.

"All

right,' Nina said reluctantly. 'I'll go home now, and be back in the morning.'

She wrapped her shawl around her and set out. Somewhere in the grove of trees

behind the house she thought she heard an owl call, but she covered her ears in

order not to hear it.

It

was not quite sunrise when Nina left her home to go back to her husband and his

father. She had not slept well, probably because she was too tired. When she

came in, the old man was choking and strangling and Joe was holding him up.

Before she could reach them, her father-in-law straightened and died.

'I tried to give him water the way you did,' Joe

exclaimed. 'I did the best I knew how. Sometimes I thought he swallowed it, and

then I'd find it spilled all over the pillow.'

'Never

mind now,' Nina reassured him. 'We have to get word to his family. He belongs

to them, now. You belong to his clan(gen) and you have to tell them.'

That

night the relatives sat up with the body. It sounded as if all the owls in the

country were in the grove, talking and arguing. Nobody dared go outside until

it was broad daylight and the owls were still.

When

the funeral and the funeral feast were over, Joe and Nina went home. They sent

the children, who had been with them all day to bed, and presently they dropped

down themselves, too tired to sit up.

Then

the owl--just one owl--called outside the bedroom window. 'He still wants

water,' Nina said. 'Joe! Get up! Give him a glass of water.'

But

Joe mumbled sleepily, and when she prodded him again he shook his head in

refusal. 'He's dead, isn't he?' he exclaimed. 'How can he want a glass of water

now?'

'He came back for a drink,' Nina

insisted. 'If you don't give it to him, something bad will happen."

It

became a point of argument between them; one of those meaningless disputes that

arise because people are over tired and go on resisting each other as if they

were fighting the whole world. On the forth night, Nina could stand it no

longer. She herself got up out of bed and set a glass of water on the back

porch. The owl was still.

After

breakfast, Joe got up and stretched. 'I'll hitch up the wagon and get in a load

of firewood,' he said. 'We've almost used up what we had, what with that feast,

and my not having time to go and get more.'

'All

right,' Nina agreed. She herself felt more tired than ever, drained and

exhausted as she had not been before. The children had gone off to school and

she forced herself up from the table and began to gather the dishes and pile

them by the sink. The window by the sink overlooked the yard and she watched

Joe throw the harness over the horses' backs and lead them up to the wagon

shafts. The horses hadn't been worked all those days and were frisky. Joe got

them harnessed and was just swinging himself into the wagon seat when the owl

swooped across the yard.

The

horses spooked. Joe was thrown between the shafts of the wagon and by the time

the horses were stopped by the yard fence and Nina reached him, he was hanging

limply upside down by his broken leg, unconscious.

'I

told you,' Nina muttered over and over as she worked to free him. 'I told you.

I said something bad would happen if you didn't set out the glass of water'

"

B U R I A L

C U S T O M S

The

Sac and Fox practiced four different burial customs: (1) the corpse was laid away in the branches of a tree or upon a

scaffold, (2) it was placed in a

sitting posture, with the back supported, out on the open ground, (3) it was seated in a shallow grave

with all but the face buried and a shelter was placed over the grave, (4) there was complete burial in the

ground. To show and express grief for

the dead, they blackened their faces with charcoal, fasted and abstained from

the use of vermilion and ornaments in dress.

D R E S S

A

Sac warrior's appearance would be of a well developed body attired in

breechcloth and beaded moccasins. His scalp lock would be treated in vermilion

and yellow; the face would be streaked in blue, yellow and red; occasionally a

string of bear claws around the neck and beaded ear bobs enhanced the

individual's appearance.

A

Fox warrior's appearance might consist of a headress of dyed-red horsehair tied

in such a manner to the scalp lock as to present the shape of a Roman helmet.

The rest of the head would be clean shaven and painted. Breechcloths, moccasins and leggings were

standard attire while the rest of the upper part of their bodies would be

painted, marked the warrior's appearance. The paintings on the chest, shoulders

and back often included the print of a hand in white clay.

S T A R L O R E

As

a people who lived close to the earth the Musquakie (Fox) were aware of

weather, seasons and the stars. For every productive activity was and still is

controlled to some extent by nature and these people recognized this fact.

Today

much of the Sac and Fox star lore has been lost for several reasons. First, the timing of ceremonies was

dependent on secret knowledge, revealed only by shamans, their religious leaders,

handed down only to those who were to succeed them. Secondly, the

constellations known to these tribes did not have European counterparts.

Thirdly, the white recorders who transcribed the data were unfamiliar with the

astronomy knowledge of their own culture.

Saukie Warrior, His Wife, and a Boy

1861/1869 by

George Catlin, Paul Mellon Collection ©1999 National Gallery of Art, Washington

D.C.

In

the following fragment of a larger myth which has been lost, a Fox explains the

story of the constellation known to us today as the Great Bear. The formalized

opening; "They say that, a long time ago…' indicates the story does not

come from the teller's personal time-frame. The formalized ending also

indicates that this is a recounting of a part of a greater myth, rather than in

telling a 'little story'.

The source of the

following myth is derived from the linguistic text recorded by William Jones

and translated by Truman Michelson.

" They

say that once, a long time ago, it was early winter. It had snowed the night

before and the first snow still lay fresh on the ground. Three young men went

out to hunt at the first light, early in the morning. One of them took his

little dog, named Hold Tight, with him.

They

went along the river and up into the woods coming to a place on the side of a

hill where the shrubs and bushes grew low and thick. Here, winding among the

bushes, the hunters found a trail and they followed it. The path led them to a

cave in the hillside. They had found a bear's den.

'Which

of us shall go in and drive the bear out?' the hunters asked each other.

At

last the oldest said, 'I will go.'

The

oldest hunter crawled into the bear's den and with his bow he poked the bear to

drive him out. 'He's coming ! He's coming !' the hunter in the cave called out

to his companions. The bear broke away from his tormentor and out of the cave.

The hunters followed him.

'Look

!' the youngest hunter cried. 'See how fast he's going ! Away to the north, the

place from whence comes the cold, that's where he's going !' The hunter ran

away to the north, to turn the bear and drive him back to the others.

'Look

out !' shouted the middle hunter. 'Here he comes ! He's going to the east, to

the place where midday comes from.' And away he ran to the east, to turn the

bear and drive him back to the others.

'I

see him !' cried the oldest hunter. 'He's going to the west, to the place where

the sun falls down. Hurry, brothers ! That's the way he's going…' he and his

little dog ran as fast as they could to the west, to turn back the bear.

As

the hunters ran after the bear, the oldest one looked down. 'Oh,' he shouted.

'There is Grandmother Earth below us. He's leading us into the sky ! Brothers

let us turn back before it's too late.'

But

it was already too late. The sky bear had led them too high. At last the

hunters caught up with the bear and killed him. The men piled up maple and

sumac branches and on the pile of boughs they butchered the bear. That is why

those trees turn blood-red in the fall.

Then

the hunters stood up. All together they lifted the bear's head, and threw it

away in the east. Now in the early morning of winter, a group of stars in the

shape of the bear's head will appear low on the horizon in the east just before

daybreak.

Next,

the hunters threw the bear's backbone away to the north. At midnight, in the

middle of winter, if you look north you will see the bear's backbone there,

outlined in the stars.

At

any time of the year, if you look at the night sky, you can see four bright

stars in a square, and behind them three bright stars and one tiny dim one. The

square is the bear, the three running behind him are the hunters, and the

little one that you can barely see is the little dog named Hold Tight.

Those

eight stars move around and around the night sky together all year long. They

never go in to rest, like some of the other stars. For until the hunters catch

up with the bear, they and their little dog can never rest.

That

is the end of that story. "

G O V E R N M E N T

The

Fox and the Sac were so closely associated that these two distinct tribes are

usually considered to have been a single tribe. Although joined in very close

alliance after 1734, the Fox and the Sac maintained separate traditions and

chiefs. This was very apparent when Fox and Sac chiefs at the insistence of the

United States were forced to sign the same treaty. However, the signatures

always appear in distinct two groupings, one for the Fox and the other for the

Sac. Both tribes have been described as extremely individualistic and warlike.

Both the Fox and the Sac had a strong sense of tribal identity and were never

reluctant to chose their own path. The French found both tribes independent and

very difficult to control.

Descent

was traced through their patrilineal clans: Bear, Beaver, Deer, Fish, Fox,

Ocean, Potato, Snow, Thunder, and Wolf. Politically, the Fox and Sac had more

central organization than with other Algonquin tribes which probably was a reflection

of the many wars they had fought. The tribal councils of their chiefs wielded

considerable authority.

Noted

for their fighting ability and efficient political administration, the Sac were

widely respected throughout the Mississippi, Rock and Illinois River

watersheds.

The

Fox, though not enjoying the same prestige as the Sac, were descended from the

same Algonquin stock. Besides being more warlike, the Fox were also stingy,

avaricious and passionate. Their bravery, however, was proverbial while their

exposure to whites had produced improvidence and addiction to liquor; because

of these shortcomings they were content in following the political lead of the

Sac.

It

should be noted that the Fox were the only Algonquin tribe to fight a war with

the French(actually, two wars). The French

enjoyed good relations with every other Algonquin tribe in the Great Lakes(including the Sac), but the Fox were antagonistic

from the moment of their first meeting with the French. It seems likely that

the Fox had taken the brunt of the fighting in Michigan with French trading

partners during the 1630s and 40s and were well-aware where the steel weapons

used against them had come from. (Some of the famous

Sac chiefs were Keokuk and Black Hawk.

Keokuk has an Iowa city named after him and is the only Native American

ever honored with a bronze bust in the U.S. Capitol. His likeness has also

appeared on American currency. The famous Olympian, Jim Thorpe (Wathohuck or

Bright Star) was a Sac/Potawatomi).

Early

in the 1700's, a reprisal by the Ojibwa, backed by the French, drove the Fox to

forge a close confederation with the Sac. This would mark both tribes as one

nation until the 1850's. The incident creating this close confederation came

about in this manner.

The

Fox had harassed French traders causing the French to incite the Ojibwe against

the Fox. During the ensuing warfare the Fox sought refuge among the Sac. Though

the Sac Nation were friendly with the French, they gave sanctuary to the Fox,

refusing to surrender them. This angered the French who then vented their wrath

on both tribes and forced them to migrate. The newly confederated Nation then

jointly attacked the Illini Confederacy for new lands that would later

encompass the region north and west of the Illinois River.

Fox

and Sac chiefs fell into three categories: civil, war, and ceremonial. Only the position of civil chief was

hereditary---the others determined by demonstrated ability or spiritual power. The authority for enforcing the laws of

their society resided in the civil chiefs and the Grand Council, composed of

chiefs and adult braves. The posts of the civil chiefs were many, the first

being hereditary. Actual power was exercised by the chief who displayed

bravery, good oratory skill and wisdom. Even this individual found it expedite

to bow to the wishes of the tribal Grand Council; which in the final analysis

wielded the authority of the confederated Nation.

Power

to lead a raiding party generally rested with anyone. Whenever the individual

wished to organize a raiding party; prayer and fasting was undertaken to

communicate with the Great Spirit. After receiving some sign or omen, he was

able to rally others to his group. Great emphasis was placed upon skill and

valor in combat, that there were always young Indians ever ready for war. If

the individual could announce the Great Spirit had informed him of the location

of some unsuspecting band of Sioux, Osage or Menominee there was no difficulty

in recruiting his force. Individually, those wishing to join the raid would

approach the leader's lodge and agree to place themselves under his leadership

for the raid's duration.

Besides the civil chiefs, both nations recognized a group who were themselves the elite of the warriors, granting to all the members of this group the special title of war chief. These individuals retained this title only so long as they maintained a reputation for valor, wisdom and resourcefulness. Actual leadership in this group rested with the individual who was able to attract sufficient numbers to himself. Dreams and visions likewise played an important role in this special class.

John Hall a white man who had spent considerable time among

the Sac in the 1830’s writes of the Sac form of government:

“.

. . the office of the chief of the Sauks is partly elective and partly

hereditary. The son is usually chosen

as the successor of the father, if worthy, but if he be passed over, the most

meritorious of the family is selected.

There are several of these dignitaries and in describing their relative

rank they narrate a tradition. They say

that a great while ago their fathers had a long lodge, in the center of which

were ranged four fires. By the first

stood two chiefs, one on the right hand who was called the Great Bear, and one

on the left hand was called the Little Bear.

These were the Peace or Village Chiefs.

They were the rulers of the tribe, the Great Bear the Chief and the

other next in authority. At the second

fire stood two chiefs, one on the right was called the Great Fox, and the one

on the left was called the Little Fox.

These were the War Chiefs or Generals.

At the third fire stood two braves, who were called respectively, the

Wolf and the Owl. At the fourth fire

stood two others who were the Eagle and the Tortoise. These last four were not

chiefs but braves of high reputations who occupied high places in the council

and persons of influence, in peace or war.

The lodge of the four

fires may have existed in fact or the tradition may be merely

metaphorical. The chiefs actually rank

in the order presented in this legend and the nation is divided into families

or clans, each of which is distinguished by the name of an animal. Instead of being eight chiefs there are now

twelve. The place of the Peace Chief,

or Headman, confers honor rather than power and is by no means a desirable

situation, unless the person has popular talents. He is nominally the first man in the tribe and presides over

councils. All acts of importance are

done in his name. But his power and

influence depends on his personal weight of character; and when he happens to

be a weak man, the authority is virtually exercised by the War Chief. He is expected to administer inflexible

justice and be generous and must entertain his people occasionally with feasts

and be liberal in giving presents. If

anyone wishes to borrow a horse on a emergency, that person must approach this

chief with his request. When a weak

person succeeds to the hereditary chieftaincy, he becomes a tool in the hands

of the War Chief, who commands the braves and young men and controls the

elements of power.

The principal War Chief is

often, therefore, the person whose name is most widely known and frequently

confused with the Headman. The station

of the War Chief is not hereditary, nor can it properly be said to be elective,

for although in some cases of emergency, a leader is formerly chosen. They usually acquire reputation by success

and rise gradually into confidence and command. The most distinguished warrior, especially if he be a man who is

popular, by tacit consent becomes the War Chief. . .”

L I F E S T Y L E

The

confederated Nation exhibited considerable order in their social organization.

Every family belonged to one of several grouping or 'gens'. Membership in a gen which had such names as

Bear, Wolf, Thunder or Sturgeon was hereditary. The gens were important for the

transmission of property and held religious significance especially since most

of the tribal

ceremonials

employed the concept.

Generally,

the heaviest concentration of Sacs were settled along the banks of the

Mississippi River between the mouths of the Des Moines and Rock Rivers. Along the banks of the Mississippi, from the

mouth of the Rock River to Prairie du Chien, a large population of Fox resided

in scattered villages. The physiographic division of Illinois called the

Galesburg Plain was considered home to the Fox; but from time to time various

portions of the area were contested by the Kickapoo and Potawatomi.

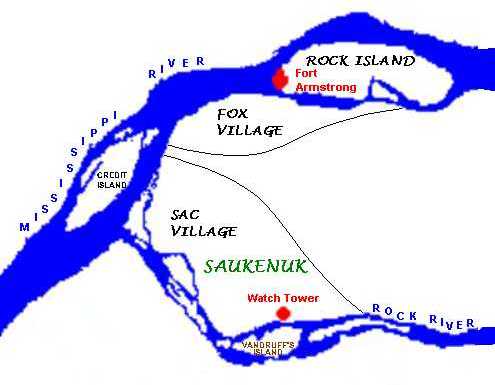

The

largest Sac village, Saukenuk, was located on a point of land between the Rock

River and the Mississippi. It was occupied by a large majority of the Sac

Nation and is estimated to have contained over a hundred lodges(hodensode) in 1817. Extensive bluegrass fields

surrounded the village furnishing ample pasturage for horses. The rivers teemed

with fish and on the fertile prairie which paralleled the Mississippi, the

women of Saukenuk and adjoining villages tilled acres of corn.

They

raised enough corn to allow for surplus to be sold to the traders; pumpkins,

beans and squash were also cultivated. From the neighboring river bluffs gushed

springs of clear water, while the land surrounding them supplied an abundance

of berries, apples, plums and nuts enhancing their diet.

The

close social and political organization between the two tribes strengthened

their unity despite the migratory mode of life. Villages like Saukenuk were

generally occupied only between hunting trips.

One

important difference between the Fox and Sauk and neighboring tribes was they

usually maintained large villages during the winter. Otherwise their housing

was typical for the region. Large communal buffalo hunts, especially after they

acquired horses in the 1760s, were conducted in the fall and provided much of

their meat during winter, but like other Great Lakes Algonquin, when the Fox or

Sauk wanted to hold a real feast for an honored guest, the main course was dog

meat from which the expression "putting

on the dog" has come.

In

the spring, following the winter hunt, the Indians would return, plant their

crops, and then deal with the company traders. On their arrival at the village

they would open the cache of provisions which was left behind the previous

fall. The cache was cunningly hidden by sod and blended in with the rest of the

prairie. In it were dried corn, squashes, beans and crab apples wrapped in bark

and would afford a welcome relief from the Spartan diet of the winter's hunt.

After

the planting was finished, negotiating with the traders would begin. After which the gens held other feasts with

dances on a regular schedule. The Indians would occasionally disperse in small

hunting parties; following game and an unsuspecting band of Osage. The Fox

enjoyed a reputation in and were particularly active in the production of

metal. Their annual output, by some estimates, was of 3,000 to 4,000 pounds of

smelted lead, most of which went to the traders. Roughly two months later the

hunters, lead miners and fishermen would reassemble at the village to share the

products and indulge in feasts, dances and games. With a bountiful harvest,

feast would follow feast, resulting in dysentery being widely prevalent causing

numerous deaths.

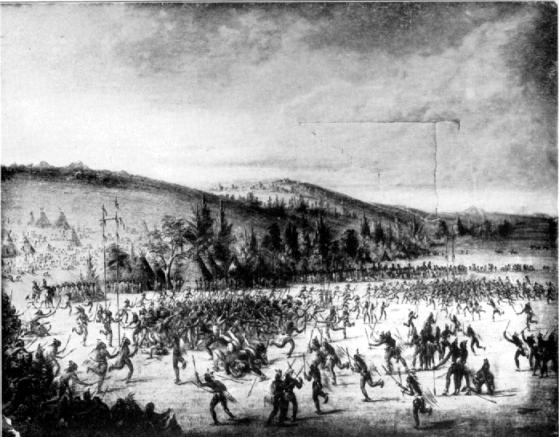

Among

the favorite recreation was horse racing and ball games played out on the open

prairie. The ball game, a variant of lacrosse, was played on a field measuring

about 200 to 300 feat in length. The games were held by bands, or villages and

the warriors fortified themselves by fasting and ceremonials, armed with

rackets, they turned the sport into a modified form of mayhem. Everyone wagered

guns, horses, blankets and other property on the outcome of the games and

races.

Recreation

came to a halt after the crops were in. The Tribal Council of the village would

allot hunting areas for the winter and fix a date for departure. In late

September the village crier announced the date to all. The last hours were

devoted to final preparations and a food cache was concealed by each family to

await their return from the winter hunt.

The

bands upon reaching their allotted hunting grounds settled down and hunted

until the season of intense cold arrived. They generally grouped themselves in

the vicinity of trading posts and waited out the worst of winter in their

lodges wrapped in mats and skins.

When

the melting snows and warm breezes blew across the land heralding the approach

of spring, the cycle would begin anew.

LACROSSE MATCH

K E O K U K

Around

1780 the half-breed daughter of a French trader gave birth to a son at the

Saukenuk village near present-day Rock Island in Illinois. Although not a chief by birth, the young Sac

named Kiyokag or Keokuk rose to the position through political maneuvering and

a flare for negotiations. He realized

early in his career it was best to steer clear of any direct confrontation with

the white man. When tensions began to increase at Saukenuk, he convinced many

of his people to cross over into Iowa and make camp on the Iowa River near

Toolesboro.

An

older Sauk warrior, Black Hawk, convinced the rest of the group to stay and

defy the American intruders. Eventually, the Illinois militia burned the

village and forced the remnant to join the younger chief in Iowa. Black Hawk refused to give up. Soon he was

stirring up dissension within the tribe and declaring war. Kiyokag cleverly

addressed the problem by agreeing to fight only if the women, children, and

elderly were first put to death to spare them the agony of sure defeat.

Most

of the tribal leaders backed down, but Black Hawk's band crossed the river at

Oquawka and went on to fight what came to be known as the Black Hawk War. The war lasted only three months, and

Kiyokag's wisdom was proven after Black Hawk's defeat. He also was able to

convince the United States to allow his people to remain in southeast Iowa

after the Treaty of 1832 forced the Sac and Fox to relinquish the eastern third

of the state. The Sac generally

inhabited the land to the south of the Quad Cities, while the Fox resided to

the north. Because of Kiyokag's loyalty

he was formally recognized by the United States government as the supreme chief of the confederated tribes of Sac

and Fox; thereby, giving him overall authority over the Iowa Indians.

As

a direct result of his non-threatening demeanor, the small strip of land along

the Iowa River was given to the Sac and designated the Keokuk Reserve. The chief attempted to live in peace with

his neighbors and bring harmony to the allied tribes for several more

years. Although they were constantly

asked to move to make room for settler expansion, the Sac and Fox Nation

remained obedient under Kiyokag's leadership.

After

1838, the year Black Hawk died, they

camped at Agency near Ottumwa and Fort Des Moines. In 1845, after selling their land holdings to repay huge debts

owed to dishonest traders and whiskey peddlers, Kiyokag led his people away

from Iowa and into the state of Kansas, where he died in 1848. Some say he had become an alcoholic and died

from a severe attack of delirium tremens.

Others claim he was killed by a member of his own tribe. Historians are not really sure what happened to him. The wisdom and congeniality of the old chief also made him an

easy choice for namesake of a new settlement at the "Foot of the

Rapids" south of Montrose.(Keokuk, Iowa)

In

1883 the remains of Kiyokag, fondly referred to as Chief Keokuk, were brought

from Kansas and placed in a sandstone monument erected in his honor. A bronze

statue was added to the top of the monument in 1913. Interestingly, the statue is not of Keokuk, but rather it is of a

generic Sioux warrior.

Black

Hawk was a Sauk (Sac) warrior noted for his resistance to the westward movement

of the white man in Illinois. The tribal name, Sauk, comes from Osakiwug,

meaning "People of the yellow earth." and belonged to the Algonquin

linguistic stock, as did the Fox and Kickapoo. The Algonquin originated in

eastern Ontario, Canada.

Black

Hawk was born in 1767 near where the Rock River flows into the Mississippi. His

native village, known as Saukenuk, was said to be the largest Indian community

in the country. The Sac Nation probably had a population of 11,000 at that

time. A residential section of the City of Rock Island, Illinois, stands there

now.

At

the age of just fifteen, Ma-ca-tai-me-she-kia-kiak joined a raid against the

Osage. He succeeded in killing and scalping an enemy warrior, which entitled

him upon return to Saukenuk to join in the scalp dance. At this early age,

Black Hawk had become a Sac warrior. A short time later, he led seven Sauk

warriors in an attack against an encampment of 100 Osages.

Ma-ca-tai-me-she-kia-kiak killed an enemy, then escaped without losing a man.

In a very short time, he became one of the most influential warriors in the

Nation.

Black

Hawk was a much-maligned man during his lifetime and the people in his day regarded

him as a "blackguard cutthroat"(he

did have a couple of notches on his tomahawk). Throughout his lifetime he was

revered as a crafty and courageous warrior, by his people and some whites. Black Hawk was often referred to as being "quarrelsome" and "surly" and was accused of

causing fear and uncertainly among the settlers in the area bordered by the

Rock and Mississippi rivers.

However,

his autobiography shows a different side of Black Hawk. Some idea of pre-reservation life survives

because Black Hawk left an autobiography, dictated to a government interpreter

in the region, and edited by John B. Patterson, an Illinois journalist, who

published it in 1833. As a transcribed

and edited oral source, its authenticity has been questioned, but even though

some of the language seems to be Patterson's, there is much to suggest it does

correctly represent the views of Black Hawk.

Because of this, all text referring to statements made by Black Hawk, in

this book, are derived from this source; except where expressly noted.

Near

the end of his days, the Aged Warrior wanted the world to know he was not the

villain he had been made out to be. He told it to a United States government

interpreter. I believe the

autobiography portrays an accurate account of Black Hawk and his involvement in

the war of 1832. I use passages from

the biography liberally to provide the aging warrior's perception of the

events. Black Hawk's War is said to be

the first in which Indians used horses.

In 1831, there were about 6,000 Sauk living at Saukenuk. Today, there are fewer full-bloods numbered

in the nation.

The

Sac village was remarkable -- laid out in lots, blocks, streets and alleys.

There was a village square surrounded by hodenosotes, or lodges which were long

bark-covered loghouses measuring from 30 to 100 feet long and from 16 to 40

feet wide. Many of them housed an

entire family, from grandparents down through grandchildren. They were finished with frames of upright

posts covered with white .

elm

bark. Running along the interior's length were benches along the wall, covered

with blankets and skins. The open area between the benches was used for food

preparation and cooking. The smoke exited out the open doors or seeped through

the roof. Fences occasionally sub-divided the interior of the lodge; melon

vines supported by the fences separated the families. A point on the bluff, 150 feet high, was called Black Hawk's

Watchtower. In surrounding white oak trees, the Sauk built lookout platforms as

smoke signal stations.

Black

Hawk's Indian name was Ma-ka-bai-mis-he-kia-kiak. He was about the same age as

Andrew Jackson, the man whom a dejected Black Hawk would confront, in

captivity, before a watching nation when his cause went down in defeat. Black Hawk was almost six feet tall and in

later years thin and hollow cheeked. His nose was hooked at the end like the

beak of the bird for which he was named. His eyes were black and beady and his

"scalp plucked bald except for a short tuft of hair on top." In his more virile years he was a

formidable-looking personality, in his native attire.

Historians

differ on his status among the Indians.

Some say his father was a chief; others that he was a medicine man. Some say Black Hawk became a chief in his

own right. Tilden's, 1880 Stephenson

County (Illinois) history calls him a chief of

the Sac and Fox Nation and a noted warrior.

Others say he was never a chief but merely a great leader in battle.

In

his biography, Black Hawk tells of falling heir to the great medicine bag of

his forefathers and of holding it sacred for the rest of his life. It was likely a bundle made of skins, fabric

or birch bark and contained a collection of charms, braids of sweetgrass, a

buffalo tail, a hawk skin and other objects and thought to have magical

powers.

"Before I take leave of the public," Black Hawk told the interpreter at the conclusion of his

story, "I must

contradict the stories that accuse me of having murdered women and children

among the whites. This is false. I never did, nor have I any knowledge that any

of my nation ever killed a white woman or child..." He said his hand

had never been raised against any but warriors. "We can only judge of what is proper and right by our standard of

right and wrong, which differs widely from the whites, if I have been correctly

informed. The whites may do bad all their lives, and then, if they are sorry

for it when about to die, all Is well! But with us it is different: we must

continue throughout our lives to do what we conceive to be good. If we have

corn and meat, and know of a family that have none, we divide with them. If we

have more blankets than sufficient, and others have not enough, we must give to

them that want.

But I will presently explain our customs, and the

manner we live. . . Our village was situated on the north side of Rock river,

at the foot of its rapids, and on the point of land between Rock river and the

Mississippi. In its front, a prairie extended to the bank of the Mississippi;

and in our rear, a continued bluff, gently ascending from the prairie. (In the

1882 edition the following sentence appears here: "On its highest peak our

Watch Tower was situated, from which we had a fine view for many miles up and

down Rock River, and in every direction.") On the side of this bluff we had our cornfields,

extending about two miles up, running parallel with the Mississippi; where we

joined those of the Foxes whose village was on the bank of the Mississippi,

opposite the lower end of Rock island, and three miles distant from ours. We

have about eight hundred acres in cultivation, including what we had on the

islands of Rock river. The land around our village, uncultivated, was covered

with bluegrass, which made excellent pasture for our horses. Several fine

springs broke out of the bluff, near by, from which we were supplied with good

water. The rapids of Rock river furnished us with an abundance of excellent

fish, and the land, being good, never failed to produce good crops of corn,

beans, pumpkins, and squashes.

We always had plenty-our children never cried with hunger, nor our

people were never in want. Here our village had stood for more than a hundred

years, during all which time we were the undisputed possessors of the valley of

the Mississippi, from the Ouisconsin to the Portage des Sioux, near the mouth

of the Missouri, being about seven hundred miles in length.

At this time we had very

little intercourse with the whites, except our traders. Our village was

healthy, and there was no place in the country possessing such advantages, nor

no hunting grounds better than those we had in possession.

If another prophet had come to our village in those days, and told us

what has since taken place, none of our people would have believed him. What!

to be driven from our village and hunting grounds, and not even permitted to

visit the graves of our forefathers, our relations, and friends?

This hardship is not known

to the whites. With us it is a custom to visit the graves of our friends, and

keep them in repair for many years. The mother will go alone to weep over the

grave of her child! The brave, with pleasure, visits the grave of his father,

after he has been successful in war, and repaints the post that shows where he

lives! There is no place like that

where the bones of our forefathers lie, to go to when in grief. Here the Great Spirit will take pity on us!

But, how different is our

situation now, from what it was in those days! Then we were as happy as the

buffalo on the plains-but now, we are as miserable as the hungry, howling wolf

in the prairie! But I am digressing from my story. Bitter reflection crowds

upon my mind, and must find utterance. .

When we returned to our

village in the spring, from our wintering grounds, we would finish trading with

our traders, who always followed us to our village. We purposely kept some of

our fine furs for this trade; and, as there was great opposition among them,

who should get these skins, we always got our goods cheap. After this trade was

over, the traders would give us a few kegs of rum, which was generally promised

in the fall, to encourage us to make a good hunt, and not go to war. They would

then start with their furs and peltries for their homes.

After this trade was over,

the traders would give us a few kegs of rum, which was generally promised in

the fall, to encourage us to make a good hunt, and not go to war. They would

then start with their furs and peltries for their homes.

Dance to the Berdache - Saukie

1861/1869 by

George Catlin, Paul Mellon Collection,

©1999 National Gallery of Art,

Washington D.C.

Our old men would take a

frolic (at this time our young men never drank). When this was ended, the next thing to be done was

to bury our dead (such as had died during the year). This is a great medicine feast. The relations of those who have

died, give all the goods they have purchased, as presents to their

friends-thereby reducing themselves to poverty, to show the Great Spirit that

they are humble, so that he will take pity on them. We would next open the

cashes [sic], and take out corn and other provisions, which had been put up in

the fall,-and then commence repairing our lodges. As soon as this is

accomplished, we repair the fences around our fields, and clean them off, ready

for planting corn. This work is done by our women. The men, during this time,

are feasting on dried venison, bear's meat, wild fowl, and corn, prepared in

different ways; and recounting to each other what took place during the winter.

Our women plant the corn,

and as soon as they get done, we make a feast, and dance the crane dance, in

which they join us, dressed in their best, and decorated with feathers. At this

feast our young braves select the young woman they wish to have for a wife. He

then informs his mother, who calls on the mother of the girl, when the

arrangement is made, and the time appointed for him to come. He goes to the

lodge when all are asleep (or pretend to be), lights his matches, which have

been provided for the purpose, and soon finds where his intended sleeps. He

then awakens her, and holds the light to his face that she may know him-after

which he places the light close to her.

If she blows it out, the ceremony is ended, and he

appears in the lodge the next morning, as one of the family. If she does not

blow out the light, but leaves it to burn out, he retires from the lodge. The

next day he places himself in full view of it, and plays his flute. The young

women go out, one by one, to see who he is playing for. The tune changes, to

let them know that he is not playing for them. When his intended makes her

appearance at the door, he continues his courting tune, until she returns to

the lodge. He then gives over playing, and makes another trial at night, which

generally turns out favorable. During the first year they ascertain whether

they can agree with each other, and can be happy--if not, they part, and each

looks out again. If we were to live together and disagree, we should be as

foolish as the whites. No indiscretion can banish a woman from her parental

lodge- no difference how many children she may bring home, she is always

welcome--the kettle is over the fire to feed them.

The crane dance often lasts

two or three days. When this is over, we feast again, and have our national

dance. The large square in the village is swept and prepared for the purpose.

The chiefs and old warriors, take seats on mats which have been spread at the

upper end of the square-the drummers and singers come next, and the braves and women

form the sides, leaving a large space in the middle. The drums beat, and the

singers commence. A warrior enters the square, keeping time with the music. He

shows the manner he started on a war party- how he approached the enemy-he

strikes, and describes the way he killed him. All join in applause. He then

leaves the square, and another enters and takes his place. Such of our young

men as have not been out in war parties, and killed an enemy, stand back

ashamed-not being able to enter the square. I remember that I was ashamed to

look where our young women stood, before I could take my stand in the square as

a warrior.

What pleasure it is to an

old warrior, to see his son come forward and relate his exploits--it makes him

feel young, and induces him to enter the square, and "fight his battles

o'er again."

This national dance makes

our warriors. When I was travelling last summer, on a steam boat, on a large

river, going from New York to Albany, I was shown the place where the Americans

dance their national dance (West Point); where the old warriors recount to their young men,

what they have done, to stimulate them to go and do likewise. This surprised

me, as I did not think the whites understood our way of making braves.

When our national dance is over-our

cornfields hoed, and every weed dug up, and our corn about knee-high, all our

young men would start in a direction towards sundown, to hunt deer and

buffalo-being prepared, also, to kill Sioux, if any are found on our hunting

grounds-a part of our old men and women to the lead mines to make lead-and the

remainder of our people start to fish, and get mat stuff. Every one leaves the

village, and remains about forty days. They then return: the hunting party

bringing in dried buffalo and deer meat, and sometimes Sioux scalps, when they

are found trespassing on our hunting grounds. At other times they are met by a

party of Sioux too strong for them, and are driven in. If the Sioux have killed

the Sacs last, they expect to be retaliated upon, and will fly before them, and

vice versa. Each party knows that the other has a right to retaliate, which

induces those who have killed last, to give way before their enemy-as neither

wish to strike, except to avenge the death of their relatives. All our wars are

predicated by the relatives of those killed; or by aggressions upon our hunting

grounds.

The party from the lead

mines bring lead, and the others dried fish, and mats for our winter lodges.

Presents are now made by each party; the first, giving to the others dried

buffalo and deer, and they, in exchange, presenting them with lead, dried fish,

and mats.

This