CHAPTER

THREE

WHITE WORLD

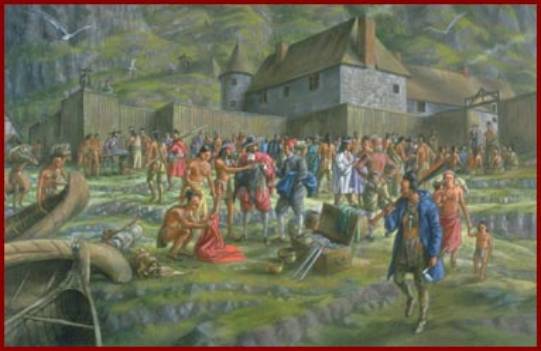

When the French in Canada founded their first permanent colony, Quebec, in 1608, the fur trade was already an established enterprise around the Gulf of Saint Lawrence for at least sixty years. The pelts obtained from the Indians, especially beaver, was their main occupation.

First Quebec Settlement, 1608

From Champlain’s The Voyages 1613 National Library of Canada image from

the Virtual Museum of New France

As

a result of this trade, the Redman was fast becoming dependent upon the basic

essentials that were supplied by the traders, such as kettles and

hatchets. The goodwill generated by

this trade enabled the French to learn woodland skills. It contributed to their knowledge of winter

snowshoe traveling, the making and use of birch bark canoes, and even supplied

the native guides to man them. The

English, on the other hand, were generally intolerant of the Indians, seeking

to destroy the Redman's presence around their settlements whenever

possible. The Indian was in turn

strengthened and weakened through his white encounters.

It was in this

timeframe that the Great League (or Five Nations

Iroquois) shaped the crucial chapter in the story of colonial North

America. It came about this way:

The French were good friends with the Huron for some time. The founder of present day Quebec, Samuel de Champlain, who was then a lieutenant of the owner of a French fur trade monopoly started out with a Huron war party toward the lake that now bears his name. Here the group engaged a rival war party of Iroquois and Champlain managed to win the battle for the Huron, single-handedly, against the small party of the Huron's hated enemies.

Samuel de Champlain

(1567-1635)

Samuel killed two and wounded the third member of the

hostile band, despite their wearing arrow-proof body armor of plaited

sticks. The thunder, lightning and

smoke from his blunderbus would echo down the corridors of time for the next

hundred and fifty years. The enemy war

party had been Mohawk and for this the Iroquois nursed a deadly animosity

toward the French.

By

the year 1614, the Dutch had built a trading post near modern-day Albany, on

the Hudson River. These interlopers

were likewise interested in securing the services of the region's Indian tribes

as possible district jobbers. The next

quarter of a century would witness the Iroquoian Confederacy acting as fur

salesmen to procure guns from the Dutch or any other European power who was

willing to trade with them.

As

the spheres of influence expanded, clear areas of contention and conflict came

into being between the Indians and the French, Swedish, Dutch and English

interests. The Indian Nations were

being sucked into this maelstrom mainly because of their trade with the

Europeans. There were still tribes far

enough from the settlements to remain, for the time being, reasonably

independent. Two distinct frontiers had

developed by this time; one Indian- versus-Indian, the other stimulated by

European interference. It was from

these two frontiers that the combined winds reached gale proportions; affecting

and determining the course of Early North American history.

The

Indian-versus-Indian frontier centered on competition among the tribes to

secure the best trade agreements for themselves and control prime fur

country. The latter frontier was

directly influenced by the increasing white population infringement on their

tribal lands and the resulting decline of game animals from over-hunting.

Replica of a Blunderbus

The

Great League played the determining role in shaping this Indian-versus-Indian

conflict in the northeast region. Their

strategic location, coupled with the fact that they traded with whomever

offered the best deal, gave European powers justifiable reasons to doubt where

their loyalty lay.

During the first half of the 1600's, the Iroquois were in

constant agitation with their neighbors to the north and west, the Montagnais,

Huron and the long established river traders--the Ottawas. Several attempts to form a confederacy with

the Great League were rebuffed by the Huron, because of French interference.

The

Huron Nation traded exclusively with New France channeling in whole canoe

fleets of prime pelts taken from the country to the west and north of the Great

Lakes. The French were not about to

have this setup jeopardized, if they could prevent it, and they feared more to

lose it to the independent Iroquois.

French

interests always managed to stir up anti-Iroquois sentiment whenever required

through their missionaries. The Huron

were of Iroquoian stock but the missionaries always differentiated between the

two, calling the Huron the 'good

Iroquois' and the Great League 'those

demons, tigers or wolves'.

Epidemics related to their white contact and the constant feuding with

their neighbors took a heavy toll on the Huron Nation. From an estimated population of 30,000 in

the 1630's they declined to about 10,000 by the 1650's.

The

Great League capitalized on the Huron's rapid decline. In 1648 Mohawk and Seneca warparties broke

the truce established between them and the Huron; because of inter-League

tribal politics. The Iroquoian

statesman-councilor Skandawati, Onondaga, invoked the ultimate diplomatic

protest of killing himself over this matter.

Still the breach of truce prevailed.

In

the winter of 1648-49, 1,000+ warriors of the combined Mohawk and Seneca

Nations invaded the heartland of the Huron, camping in the vicinity of Georgian

Bay and somewhat north of modern day Toronto, Canada. Living off the land without the Huron even suspecting their

presence as they prepared for a massive strike.

In

two days of heavy hand-to-hand combat two Huron villages were over-run and

plundered by the intruders before being repulsed from the third and vanishing

into the woods with their captives and loot. Panic spread like wildfire throughout the Huron Nation, which had

not suffered a serious defeat, causing most of the tribesmen to flee in the

dead of winter. By winter's end many

had died from exposure and starvation, while some of the survivors would continue

to flee for years.

The

Age of the mighty Huron Confederacy, which had outnumbered in population nearly

three-to-one over the Iroquoian Confederacy, was over. The refugees would later find homes among

their conquerors, the neutral tribes, or the Erie Nation. Others scattered to the four winds calling

themselves what had been their name for their confederacy--the Wendat, becoming

the Wyandot, in our literature. The

feelings of utter defeat, where no serious defeat was present, sent shock waves

of panic rippling throughout the Indian world.

Tribes boarding the Great League were thrown into turmoil which the

League interpreted as hostility and anti-Iroquoian agitation.

Part of the Iroquoian Confederacy to the southwest of the

Huron was referred to as the Neutral Nations by the French because of the

un-involvement in the fracas of the Mohawk-Seneca expedition against the

Huron. These tribes met their doom at

the hands of the League by 1651. The

next Iroquoian Nation--the Erie, were attacked by the Great League in

1653. A counter-attack against the Erie

followed the next summer taking by storm an important Erie village; but two

more years were required before this Nation was vanquished by the "Tree of

Peace".

Early in 1653, Native

conflicts paralyzed the trade. According to Jesuit missionary François-Joseph Le

Mercier, New France was on the verge of bankruptcy:

". . .At no time in the past were the beavers

more plentiful in our lakes and rivers and more scarce in the country's stores

[...] The war against the Iroquois has exhausted all the sources [...] the

Huron flotillas have ceased to come for the trade; the Algonquin are

depopulated and the remote Nations have withdrawn even further in fear of the

Iroquois. The Montréal store has not purchased a single beaver from the Natives

in the past year. At Trois-Rivières, the few Natives that came were employed to

defend the place where the enemy is expected. The store in Québec is the image

of poverty . . ."

It

was during the war between the Iroquois and the Erie that the French and Great

League honored a truce. When this war

between the two Indian Nations ended, the French, broke the pact and launched a

full scale military invasion of the Iroquoian Confederacy's territory. They burned villages and cut a wide swath of

devastation, rivaling everything the League had done to their neighbors. It should have been sufficient to destroy any

Indian nation; but it wasn't. Mainly

because of the lightly populated country.

The Great League did manage to make an enforced peace with the French.

The

league was now faced with wolf-pack attacks from it's neighbors--those still

able to fight them from the north and west.

A new threat now loomed on the horizon to the south taking the shape of

the Delaware, who themselves had just given a beating to the Seneca. The Susquehanna united with the Delaware and

both Indian Nations were preparing to obliterate the Great League from the face

of the earth.

Fate intervened.

The

Susquehanna lost large numbers of their population from a sudden epidemic. English settlers quickly took advantage of

the situation. Over the objections of

the English colonial governments of Maryland and Virginia and the policies

which favored the Susquehanna Nation.

The settlers attacked the crippled tribe. Whatever was left of the Susquehanna was destroyed or absorbed

into the Great League without a major confrontation by 1675.

In

the arena of conflict the Iroquoian Great League now stood alone in blocking

the European invaders and holding the key to the interior of the North American

continent. The next two decades would see the French and English with their

Indian auxiliaries wearing away at this barrier. Iroquoian crops and villages were burned and destroyed mainly by

the French but the Indian political structure somehow managed to remain

intact. The League was, because of this

political unity, quite capable of delivering heavy reprisal raids and

frequently did.

In

1640, British traders from New England attempted to lure the Mohawk from the

Dutch by selling them firearms(violation of British law). The Dutch responded

by providing guns and ammunition in any amounts the Iroquois demanded, and the

Iroquois suddenly were the best-armed military force in North America. A

dramatic escalation of violence that was later called the Beaver Wars followed.

In

the middle 1600's, French policy had become crystallized into holding the

country west of the Appalachian Mountains; from New Orleans to Quebec. Toward this region the English frontier was

slowly but constantly advancing. In

every colonial scheme to penetrate the continent's interior, the Iroquoian

Confederacy had to be taken into account.

By this time the Dutch and Swedish interests were eliminated from the

arena. The contention and conflict now

centered between the French, Great League and British interests.

The repercussions from this three-way struggle were sending shockwaves rippling across the face of the continent's interior. Bands of Huron and Ottawa migrated westward to the upper Mississippi, fought the Sioux and were repelled and driven

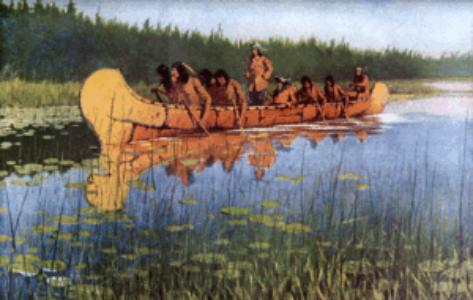

French coureurs-de-bois

back east. They joined and divided again among

themselves while others started villages at, or near, the trading posts of the

Great Lakes region. More and more bands

formed their villages around forts or end-of-the-world French trading

towns. These were settlements that were

Indian in everything but language.

The

French coureurs-de-bois(voyageurs) were at home

in the network of lakes and streams in the interior of the North American

continent and it was relatively easy to keep communications open from New

Orleans to Detroit. No attempt was made

to colonize this region, but the French missionaries tried to induce the

Indians to live in peace with one another.

The French were careful in providing an outlet for the Redman's raiding forays by channeling these drives against the English frontier settlements and English Indian allies. When the French did attempt to colonize, as in eastern Canada or in Louisiana, they were no different than their English rivals. They, too, would enter into wars of extermination against the Redman. Their success in holding the upper Mississippi and Ohio regions as long as they did was mainly because they did not form extensive settlements and shared a common enemy with the Indians: the western thrust of the English frontier. It should be pointed out that the French were weakest in the center, along the Ohio River, just the very place the British frontier was to strike the hardest.

Within a few years the Iroquois had driven the Algonquin from the lower Ottawa River and cut the trade route to the west. The French established a new post at Montreal to shorten the distance to the Great Lakes, but with Iroquois war parties in the Ottawa Valley, only large canoe convoys were able to fight their way past. By 1645 the French had been forced to sign a peace with the Mohawk which required them to remain neutral in future wars between the Huron and Iroquois.

Although

isolated, the Huron continued to trade with the French and deny the Iroquois

permission to enter their territory. After two years of diplomacy failed to

resolve this problem, the Iroquois attacked the Huron homeland. The death blow

came in March, 1649 when in a series of coordinated attacks, 2,000 Iroquois

warriors overran and destroyed the Huron Confederacy.

After

the Huron Nation had collapsed the Neutral nations fell during 1651 followed by

the Erie (1653-56). Very few escaped

death or capture by the Iroquois. A few

Tionontati and Huron fled west to the Ottawa villages at Mackinac, and then to

Green Bay. In time these

Iroquoian-speaking refugees would merge to become the Wyandot and revive the

French fur trade, but for the moment, all was lost.

The

defeat of the French allies brought no relief to the tribes in lower

Michigan. The Iroquois swept into the

peninsula and finished the task of driving them from their homes. By the late 1650s, 20,000 battered and

disorganized refugees had crowded into northern Wisconsin and were overwhelming

its resources. Many farming tribes

found it difficult to grow corn this far north, and facing starvation, they

were fighting among themselves for hunting territory.

In

the constant turmoil which prevailed, the Sac were drawn into a loose alliance

with the villages near Green Bay with their mixed populations of Fox,

Potawatomi, Menominee, Ottawa, Huron, Winnebago,

Noquet, Miami, and Mascouten. Iroquois war

parties had followed the Wyandot west and were threatening everyone, but there

were also frequent skirmishes between the Green Bay tribes and the Ojibwe to

the north and the Dakota (Santee or Woodland Sioux) in the west.

S T U R G E O N W A R

The

Sturgeon War erupted in the area in the 1660s after a Menominee village at the

mouth of a river erected a series of fish weirs which prevented sturgeon from

reaching the Ojibwe villages upstream. After the Menominee refused to remove

them, the Ojibwe attacked and destroyed both the weirs and village. The

survivors fled to their relatives at Green Bay who called on the Sac, Fox,

Potawatomi, and others to help them against the Ojibwe, and the fighting

expanded well-beyond the original antagonists.

The Fox participated in this war, but in general, they remained aloof from other tribes. Their strongest ties at this time were with the Kickapoo and Mascouten in warfare with the Illinois to the south, but in northern Wisconsin, they became involved in three-way struggle with the Ojibwe and Dakota for control of the St. Croix River Valley.

The

destruction of the Huron Confederacy in 1649 had left the French fur trade in

shambles. In danger themselves of being

overrun, the French had not intervened, and when the western Iroquois offered

peace in 1653 so they could attack the Erie, the French jumped at this

chance.

To

protect this fragile truce, the French halted their travel to the Great Lakes,

but to keep their fur trade alive, they continued to invite their old trading

partners to bring their furs to Montreal. truce, the French halted their travel

to the Great Lakes, but to keep their fur trade alive, they continued to invite

their old trading partners to bring their furs to Montreal.

A Indian Fishing

Wier

With

Iroquois war parties haunting the entire Ottawa River Valley, this was an

extremely dangerous undertaking, but the Ottawa and Wyandot (Huron-Tionontati) were willing to try and recruited

Ojibwe warriors to help them in forcing their way to Montreal. The Iroquois attempted to stop this by going

after the source. Their war parties

journeyed to Wisconsin and began attacking just about anyone supplying fur to

the French through the Ottawa and Wyandot.

Under constant attack and with beaver dwindling near Green Bay, the

Wyandot left in 1658 and moved inland to Lake Pepin on the Mississippi River.

Most

of the Ottawa also left but went to the south shore of Lake Superior at

Keweenaw and Chequamegon (Ashland, Wisconsin)

which provided them with better access for trade with the Cree to the

north. That same year, the French peace

with the Iroquois ended with the murder of a Jesuit ambassador. Seeing this as

an opportunity to renew trade in Great Lakes, Pierre Radisson, Médart Chouart

des Groseilliers, and Father Réné Ménard ignored the official ban on travel and

accompanied the Wyandot on their return journey from Montreal. Radisson and

Groseilliers reached the west end of Lake Superior and then traveled overland to

trade with the Dakota.

The

French government showed its gratitude for their effort by arresting them on

their return to Quebec in 1660, but the Dakota meanwhile had become aware of

the value of beaver and would no longer tolerate the Wyandot presence on Lake

Pepin, and their threats during 1661 forced the Wyandot to relocate north to

Lake Superior near the Ottawa at Chequamegon.

This concentration of beaver-hunting refugees did not please the Dakota

either, and with a fourth competitor added to the contest, the three-way

struggle in western Wisconsin became increasing violent.

Meanwhile,

the French had tired of living under the constant threat of annihilation by the

Iroquois, and the king assumed control of Canada and sent a regiment of

soldiers to Quebec in 1664 to deal with them. The following year, Nicholas

Perot, Father Claude-Jean Allouez, and six other Frenchmen accompanied 400

Ottawa and Wyandot on their return to Green Bay. Although the Jesuits had

learned of the Fox and the Sac as early as 1640, actual contact did not occur

until Allouez met them in Wisconsin during 1666.

At

first, the Sac were wary of the "blackrobe," whom they suspected of

witchcraft, but relations improved. The

Fox were hostile from the onset and remained that way. The French and their fur trade had brought

nothing but grief so far, and the previous winter, the Seneca (Iroquois) had attacked a number of Fox villages

killing 70 women and children and dragging 30 prisoners away to an uncertain

fate. The Fox did not want the French

in Wisconsin and, having been on the receiving end of French weapons before,

they especially did not want them trading with the Dakota and Ojibwe.

By

1667 attacks by French soldiers on villages in the Iroquois homeland had

produced a peace which extended to French allies and trading partners in the

western Great Lakes. It lasted until

1680 and bought much needed relief for the refugee tribes. The conditions the French discovered when

they came to Wisconsin were appalling: warfare, epidemic, and near starvation

--- none of which were conducive for traade or religious conversion.

Although

intending to line their pockets and fill their churches, the French used their

control over trade goods to perform a service for Wisconsin tribes and began

acting as mediators to resolve intertribal disputes and end the warfare. Some

of their most notable successes are attributed to Daniel DeLhut (Duluth) who came to Sault Ste. Marie during

1678. Two years later DeLhut arranged a

truce between the Saulteur Ojibwe and the Dakota which endured for several

years.

Tensions

along the south shore of Lake Superior eased after Father Jacques Marquette

convinced the Ottawa and Wyandot to leave and move east to his new mission at

St. Ignace. Unfortunately, Delhut's

agreement had not included the Fox or Keweenaw Ojibwe who continued fighting

the Dakota, but it did produce unusual allies. The Fox and Keweenaw joined

forces to defeat a large Dakota war party, while the Saulteur Ojibwe allied

with the Dakota against the Fox.

The

French succeeded in ending most infighting between the refugees in Wisconsin,

but with the exception of the Saulteur Ojibwe, virtually all still considered

the Dakota as enemies. Serious problems

developed when French traders began visiting the Dakota villages to trade. The

Sac murdered two Jesuit donné and joined a Potawatomi conspiracy at Green Bay

to form an anti-French alliance. Meanwhile, the Menominee and Ojibwe of Chief

Achiganaga robbed and killed two French traders enroute to the Dakota.

DeLhut

decided to hold a European-style trial for Chief Achiganaga and the other

offenders, but he faced a revolt by several important tribes if the punishment

was too severe. In the end, DeLhut was

able to execute only one Menominee—from

a small tribe. The Beaver Wars had resumed in 1680 with Iroquois attacks

against the Illinois, and the French could not afford to offend an important

ally like the Ojibwe. With the

exception of an attack at Mackinac in 1683, the fighting during the next four

years was mainly to the south.

The

Illinois took a terrible beating, but in 1684 the Iroquois failed in their

attempt to take Fort St. Louis at Starved Rock on the upper Illinois River, a

defeat considered to be the turning point of the Beaver Wars. The French afterwards attempted to organize

an alliance of the Great Lakes Algonquin against the Iroquois, but its first

offensive was such a catastrophe that Joseph La Barre, the governor of Canada,

signed a treaty with the Iroquois conceding most of Illinois.

He

was replaced by Jacques-Rene Denonville who promptly renounced La Barre's

treaty, built new forts, strengthened old ones, and provided guns to Algonquin

allies. Coinciding with the King

William's War between Britain and France (1688-97), Denonville's new alliance

took the offensive in 1687 and began driving the Iroquois back across the Great

Lakes towards New York. Both Fox and

Sac warriors took part, but Fox participation was less than the French

expected. Instead of fighting the Iroquois with the guns they were given, the

Fox used them in western Wisconsin against the Dakota and Ojibwe.

Even

though they were well-armed, the Fox were hard-pressed and had managed to

defeat a Dakota-Ojibwe war party in 1683 only with heavy losses to themselves.

The French and Fox had traded since 1667, but relations were still

antagonistic. The Fox tolerated the

French so long as they provided firearms, but they remained hostile and

distant. The French viewed the Fox as

troublemakers and laggards in the war against the Iroquois.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

FRENCH FORTS IN THE NORTHWEST TERRITORY

1701-1763

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

1.

FORT ASCENSION—(ca.1757-1759),

Metropolis, IL (name changed to Fort

Massaic in 1759)

2.

FORT BEAUHARNOIS—(ca.??),

near Lake Pepin, on the Mississippi River

3.

FORT CREVECOEUR—(ca.1730-?),

Creve Coeur, IL—State Historic Park (fort

was also called FORT LEWIS)

4.

FORT de BUADE—(ca.??),

across the straits from FORT MICHILIMACKINAC

5.

FORT de CHARTRES—(ca.1719-1761),

Prairie du Rocher, IL

6.

FORT de RENARDS—(ca.??),

in IL

7.

FORT KASKASKIA—(ca.1756-1766),

Kaskaskia, IL

8.

FORT LA BAYA—(ca.??),

Green Bay, WI

9.

FORT LA JONQUIÉRE—(ca.1750-1754), on the west side of

Lake Pepin, near

Frontenac, MN

10. FORT MIAMI—(ca.1719-1761), Miami, IN

11. FORT MICHILIMACKINAC—(ca.1718-1760), Mackinaw, MI

12. FORT OUIATENON—(ca.1717-1761), West Lafayette, IN

13. FORT PIMITOUI—(ca.??), on the Illinois River

14. FORT PONTCHARTRAIN—(ca.1701-1761), Detroit, MI

15. FORT SANDESKI—(ca.1755-?), near Sandusky, OH

16. FORT STE. ANTOINE—(ca.??), near Lake Pepin, WI on the Mississippi River

17. FORT STE. FRANCIS—(ca.1717-1760), Green Bay, WI

18. FORT STE. JOSEPH—(ca.1755-1761), Niles, MI

19. FORT STE. XAVIER—(ca.??), near Green Bay, WI

20. FORT TAMARANS—(ca.1755-?), at or near East St. Louis, IL

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Since the fighting along the St. Croix was tying up Ojibwe warriors, the French arranged a truce between the Fox and Ojibwe in 1685. This lasted for five years until warfare renewed over hunting territory along the upper Mississippi between the Dakota and an alliance of the Fox, Ojibwe, Potawatomi, Kickapoo and Mascouten.

The

Algonquin tribes harassed French traders to keep them from supplying the

Dakota, but the Fox went beyond normal bounds when they began charging tolls to

pass through their territory. This

practice exasperated Nicolas Perot, the French commandant at La Baye (Green Bay), and he asked the Ojibwe in 1690 to make

the Fox stop. This was all the

encouragement needed. Allied with the

Dakota, the Ojibwe drove the Fox from the upper St. Croix River while a

French-Ojibwe expedition attacked the Fox village at the Fox Portage forcing

its abandonment.

After

the 1690s the Iroquois were on the defensive and near defeat. The war between

Britain and France had ended in 1697 with the Treaty of Ryswick, but the French

were unable to convince the Algonquin alliance to make peace with the Iroquois

until 1701. In the meantime, they were

losing their authority over their allies because, oddly enough, the fur trade

had become too successful.

As

victory followed victory, the French and their allies advanced across the Great

Lakes seizing most of the best beaver producing areas. Fur flowed east to Montreal in unprecedented

amounts creating a glut of beaver on the European market and the price

dropped. As profits plunged, the French

monarchy decided the time had come to heed Jesuit protests about the corruption

the fur trade was creating among Native Americans and suspended the fur trade

in the Great Lakes in 1696. Since trade

was what bound the alliance together, French authority crumpled.

This

was immediately apparent in the inability of the French to effect a truce along

the upper Mississippi. Shortages and

higher prices for trade goods combined with abuse by Coureurs de Bois (unlicensed traders) added to the crisis. French traders were robbed and murdered at

an alarming rate, and even Nicholas Perot found himself tied to a Mascouten

torture stake ready for burning. He was

saved by the Kickapoo but soon went back to Quebec and never returned to the

Great Lakes.

Besides

their continuing war with the Dakota, the Fox joined with the Winnebago during

this time to drive the Kaskaskia (Illinois) from southern Wisconsin

(1695-1700), and even the Sac managed to kill a French trader who was living

among the Dakota. Meanwhile, the

alliance became increasingly concerned the French would abandon them to make a

separate peace with the Iroquois.

The

French never did, but their allies had good reason to be suspicious. Even as they were going down in defeat, the

Iroquois sensed the problems the French trade suspension had created and

offered peace with access to British traders if the Ottawa would break with the

alliance. The Ottawa refused, but after

the peace in 1701, the lure of British trade (higher

quality and cheaper than French goods) proved irresistible.

Ottawa

and Ojibwe traders began taking their furs to Albany rather than Montreal. Other French allies followed, and the

Iroquois came closer to destroying the French with economic competition than

they had ever managed by warfare. After

several pleas to Paris, the French in Canada were finally able to convince

their government to allow a single trading post at Detroit to retain the loyalty

of the Great Lakes tribes. Responsibility

for this was given to Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac.

Cadillac built Fort Pontchartrain at Detroit in July, 1701 and

immediately invited the Ottawa and Wyandot to settle nearby. Queen Anne's War (1701-13) between Britain

and France began that year, but it had little effect in the Great Lakes. British and Iroquois traders continued

making inroads, and to keep French allies from trading with them, Cadillac

asked other tribes to come to Detroit.

The

result was exactly as it had been 50-years previous in northern Wisconsin--too

many tribes and too few resources. Even

the Ottawa, Ojibwe, and Wyandot (long-time friends) began quarreling over

territory, and in 1706 the Ottawa and Miami fought a brief war over this same

issue.

Rather

than sensing this as a warning, Cadillac kept inviting more tribes. Eventually, 6,000 Ojibwe, Wyandot, Ottawa,

Potawatomi, Miami, Illinois, Osage, and Missouria were living near

Detroit. The only thing positive about

the situation was the overcrowding in Wisconsin ended when many of the refugee

tribes left. The final straw was added

to this tense situation in 1710 when Cadillac invited the Fox. About 1,000 Fox accepted his invitation and

came east bringing with them a large number of their Mascouten and Kickapoo

allies.

Returning

to their original homeland, the Fox found it overrun with other French allies

who were not pleased to see them. Their

feelings about this can only be imagined, but the Fox apparently were not

reluctant to claim special privileges or tell the other tribes who originally

owned the area around Detroit. The

Ottawa, Huron, Peoria, Potawatomi, and Miami were in no mood to listen to this

and began pressing the French to send the Fox and their allies back to Wisconsin.

Cadillac ignored this but made no attempt to assign territories. As a result, several skirmishes occurred between the Fox and other French allies; meanwhile, the French heard rumors the Fox were negotiating with Iroquois for permission to trade with the British. In 1711 Cadillac was called back to Quebec for a meeting and left Joseph Dubuisson in charge at Fort Pontchartrain.

In

his absence, the Potawatomi and Ottawa decided to solve the Fox problem on

their own and, in the spring of 1712, attacked a Mascouten hunting party near

the headwaters of the St. Joseph River in southern Michigan. The Mascouten fled

east to their Fox allies near Detroit.

As the Fox prepared to retaliate, Dubuisson attempted to stop them, and

at this point, the Fox had just about enough from the French.

F I R S T F O X

W A R ( 1 7 1 2 – 1 7 1 6 )

The

First Fox War began when Fox, Kickapoo, and Mascouten attacked Fort

Pontchartrain on May 13th. The initial assault failed and was followed by a

siege. With over 300 well-armed

warriors pitted against 20 French soldiers inside a fort with crumbling walls,

there is good reason to ask if the Fox intended to kill the French or just

scare them. In any case, a relief party

of Wyandot, Ottawa, Potawatomi and Mississauga (Ojibwe)

arrived and fell upon the Fox from behind.

In

the slaughter which followed, more than 1,000 Fox, Kickapoo, and Mascouten were

killed. Only 100 of the Fox escaped to find refuge with the Sac(English traders called them Squawkies). Otherwise, only a few Fox returned to

Wisconsin with the Kickapoo and Mascouten. They joined the Fox who had remained

behind and made the French and their allies pay dearly for the massacre at

Detroit.

The

Fur Wars were essentially a civil

war between members of the French alliance and an indication of how much the

coalition had fallen apart after the restriction of French trade. The Iroquois must have watched with great

amusement as their enemies fought each other.

The Fox, Kickapoo, and Mascouten killed French traders and attacked

their native allies, but the French were unable to assemble a large enough

force to retaliate. It was first

necessary to repair their alliance, and this took almost three years.

The

most difficult task facing the French in Canada was to convince Paris to revive

the fur trade in the Great Lakes, but permission was not received until after

the death of Louis XIV in 1715.

Coureurs de Bois were legalized and 25 trading permits issued, and this

allowed the French to mediate disputes between the Ojibwe and Green Bay tribes

and arrange peace between the Illinois and Miami. This accomplished, the French

were ready to deal with the Fox.

A

French-Potawatomi expedition attacked the Kickapoo and Mascouten in 1715 and

forced them to make a separate peace.

Even without allies, the Fox refused to quit and gathered into a

fortified village in southern Wisconsin.

Louis de Louvigny arrived with a large number of Potawatomi, Ojibwe, and

Ottawa warriors in 1716 and laid siege (during which

the Sac brought food to the Fox), but the French and their allies were

finally forced to withdraw. Soon

afterwards, the frustrated French offered peace, and the Fox accepted,

officially ending the First Fox War. However, this was more a temporary truce

than a peace, since both sides remained bitter and distrustful of each other.

Fort

Michilimackinac

(restoration photograph)

To meet British competition, the French reoccupied old posts and

opened new ones. The more important

included: Michilimackinac, La Baye, Miamis, Ouiatenon, Chequamegon (La Pointe), St. Joseph, Pimitoui, Niagara, De Chartres, and Vincennes (Au Post). but the damage was done.

In 1727 the British opened a post in the Iroquois homeland at Oswego to

shorten the distance Great Lakes tribes had to travel for trade. The following year 80% of the beaver on the

Albany market came from French allies in the Great Lakes.

Peace between the Fox and French in 1716 did not stop the fighting

between the Fox and Peoria Nations. The

Peoria had tortured the Fox prisoners they had captured at Detroit in 1712, and

the Fox afterwards gave similar mistreatment to Peoria prisoners. In 1716 the Peoria refused to return their

Fox prisoners, and French attempts to mediate failed. War between the Fox and Peoria renewed and was complicated by

encroachments by the Fox, Kickapoo, Winnebago, and Mascouten when they began

coming south from Wisconsin to hunt buffalo on the northern Illinois prairies

without permission from the Illinois.

In 1722 the Illinois expressed their displeasure with this when

they captured Minchilay, the nephew of the Fox chief Oushala, and burned him

alive. This drew the Kickapoo,

Mascouten, and Winnebago into the war as Fox allies during 1724. The Peoria took refuge at their fortress at

Starved Rock (Utica,

Illinois) and

asked the French to intervene. A relief

expedition was sent from Fort de Chartres, but the Fox and their allies

withdrew before it arrived leaving behind over 100 of their dead.

At the same time west of the Mississippi, the Fox had joined with

the Iowa to fight the Osage, Otoe, and Missouria which disrupted the developing

French fur trade along the Missouri River.

The French held councils during 1723 with the Kansa, Pawnee, Comanche, Nakota (Yankton Sioux),

Osage, Missouria, Otoe, Iowa, Fox, and Dakota.

This brought some peace for the tribes on the Missouri River, but

fighting erupted along the Des Moines River in southeast Iowa between the Fox

and Iowa and the Osage and Missouria.

The councils had a result which the French never intended.

To fight all of their enemies, the Fox needed more allies, and

they did this by forming an alliance with the Dakota against the Illinois. After almost 70 years of constant warfare

between them, this sudden alliance of the Fox and Dakota would have made anyone

suspicious, but the French needed little help in this regard. They were becoming convinced the Fox could

not possibly be creating this much trouble on their own initiative and were

probably part of a British plot to form a secret alliance directed against

themselves.

The French decided that drastic measures would be necessary to

deal with the Fox, and most of their allies agreed with them. Besides the Illinois, they had the support

of the Mackinac Ojibwe, who were skirmishing with the Fox in northern Wisconsin

and upper Michigan, and the Detroit Tribes (Wyandot, Ottawa, Saginaw Ojibwe, Mississauga, and Potawatomi). As

they gathered their allies in preparation for war, a series of meetings were

held about the "Fox problem."

One suggestion was to relocate the Fox at Detroit where the French

garrison could watch them. For obvious

reasons, this met with a very cool reception from Detroit tribes.

Meanwhile, the French in Illinois sent an expedition with 20

soldiers and 500 Illini warriors to attack the Fox in 1726, but the Fox

anticipated its approach and withdrew.

The following year, the French made their first proposals of

genocide.

Following a war of extermination, any Fox who survived would be

sold as slaves to the West Indies. No

decision was made at the time. Although

unsure about extermination(not

an official policy until it was approved by the king in 1732), the French had decided on war. They first took the precaution of using

diplomacy to isolate the Fox from their allies. The Fox were aware of this effort but could do little about

it. The Menominee refused the Fox

request for an alliance and told them that in the event of war they would side

with the French. The power of French

trade goods caused the Dakota, Winnebago, and Iowa to withdraw their support,

and the French even won a reluctant agreement from the Sac near Green Bay.

S E C O N D F O X

W A R ( 1 7 2 8 – 1 7 3 7 )

At the beginning of the Second Fox War, only the Kickapoo

and Mascouten stood with the Fox.

Despite this, the French expedition sent against them under Sieur de

Lignery was unsuccessful, but afterwards the Fox managed to antagonize the few

friends they had. Following an argument

about the refusal of the Kickapoo and Mascouten to kill the French prisoners

they were holding, the Fox stalked out of the meeting and murdered a Kickapoo

and Mascouten on their way home.

Furious, the Kickapoo and Mascouten went over to the French in 1729.

Without

the protection of allies, the Fox were battered from all sides. During the

winter of 1729, a combined Winnebago, Menominee, Ojibwe war party attacked a

Fox hunting village killing at least 80 warriors and capturing some 70 women

and children. The Fox retaliated by

besieging the Winnebago fort on the Fox River, but the attack was abandoned

after the arrival of a relief force of French and Menominee warriors from Green

Bay. By the summer of 1730, about 1,000

of the Fox had decided to leave Wisconsin and accept an offer of sanctuary

received from the Seneca (Iroquois) in New

York. But to get there, they had to

pass through territory controlled by the Illinois. In a very uncharacteristic manner for them, the Fox actually sent

an envoy to the Illinois to ask their permission to pass, but a quarrel

developed. Perhaps as their way of

saying farewell, the Fox captured the nephew of a Cahokia chief near Starved

Rock and burned him at the stake. Angry

Illinois warriors pursued the Fox column and caught them on the open prairie

east of present-day Bloomington, Illinois.

The

Fox retreated and built a rude fort to protect their women and children. It would probably have been best if they had

kept going. The Illinois surrounded

them and sent for help, and the French and their allies descended on the Fox

fort from all directions. St. Ange

arrived in August from Fort de Chartres with 100 French and 400 Cahokia,

Peoria, and Missouria. De Villiers

brought 200 Kickapoo, Mascouten, and Potawatomi, while Reaume came from St.

Joseph (Michigan) with 400 Sac, Potawatomi, and Miami. In September Piankashaw and Wea warriors led

by de Noyelle arrived from a Miami post with instructions from the Governor of

Canada that no peace was to be made with Fox.

Apparently

some Sac ignored this order and provided the Fox with food, but it was not

enough. Surrounded by over 1,400

warriors, the Fox fought off everything, but their food and water gave out. They began throwing their children out of the

fort, telling their enemies to eat them.

Many apparently were adopted by other tribes, but the fate of their

parents was far worse. After 23 days, a

thunderstorm struck on the night of September 8th, and the Fox took advantage

of this to break out and flee. They did

not make it. The French and their

allies caught up and killed between 600 and 800 of them. There were no prisoners.

Extract of a Letter from Gilles Hocquart to the

French Minister(January 15, 1731) Hocquart in: Wisconsin Historical Collections, XVII, pp. 129-130.

(page 129)I have no doubt, Monseigneur, that you have learned,

by way of the Mississipi of the defeat of the Renard savages that happened on

September 9th last, in a Plain situated between the River Wabache and the River

of the Illinois, About 60 Leagues to the south of The Extremity or foot of Lake

Michigan, to The East South East of le Rocher in the Illinois Country. 150

French both from Louisiana and from Canada, and (page 130) many savage Tribes, to the number of 8 or

900 men, stopped them, blockaded them in their fort and compelled them to issue

from it through press of hunger; And they pursued them, killing 200 warriors;

200 women or Children met the same fate, and the remainder to the number of 4

or 500, also women and Children, were made Slaves and scattered among all the

Nations. Messieurs de Villiers, the Commandant at the River St Joseph; des

Noyelles, the commandant among the Miamis; and Messieurs de St. Ange, Officers

in Louisiana, behaved with all the bravery and Prudence that could be expected

of Them. Monsieur de Villiers, Lieutenant of the Troops, who was the senior

officer, had the Command of this Expedition. We Were greatly mortified,

Monseigneur, at not being the first to convey Information of this happy success

to you. Monsieur the general had dispatched the Sieur Villiers, the younger,

who was present in The action, to convey The news to you; But The incident that

happened to the Ship, le Beauharnois, Prevented His doing so.

I have the honor to send you by this ship,

Duplicates of several of my Letters, the first whereof relates to Monsieur de

Lignery's affair.

I remain with very profound respect, Monseigneur,

Your very humble and very obedient Servant,

HOCQUART

QUEBEC, January 15th, 1731.

The

600 Fox who had remained in Wisconsin were all that were left after this. Up to

this point, the Sac had usually maintained good relations with the French and a

relatively low profile in history, but this changed. With everyone their enemy, the Fox remembered the Sac had given

them food in 1716 and again during the siege in Illinois. They turned to the Sac to save them, and the

Sac not only gave them refuge but appealed to the French in 1733 to make peace

with the Fox.

The

answer came in 1734 when a French expedition under Sieur de Villiers

accompanied by Ojibwe and Menominee warriors arrived at the Sac village west of

Green Bay to demand the Sac surrender of the Fox. The Sac refused, and during the assault which followed, Villiers

made the fatal error of placing his body in the path of a speeding bullet. In the confusion which followed, the French

and their allies fell back to regroup, and the Sac and Fox abandoned the

village and fled west. They crossed the

Mississippi and settled in eastern Iowa in 1735.

The

French sent another expedition after them in 1736, but by this time, the French

Indian allies were beginning to have doubts about their commitment to

genocide. The Illinois Nation voiced

the general concern that if the Fox could be destroyed like this, who might be

the next victim? As things turned out,

the Illinois had good reason to worry.

Even the Ottawa, the staunchest and most anti-Fox of the French allies,

said in council that "they no longer wanted to eat the Fox." De Noyelle's expedition against the Fox and

Sac in Iowa that year ended in failure after its Kickapoo guides led him in

circles and through every swamp in western Wisconsin.

At a meeting in Montreal during the spring of 1737, the Menominee and Winnebago asked the French to show mercy to the Fox while the Potawatomi and Ottawa made a similar request on behalf of the Sac. The irony of this role reversal should not be lost--French Indian allies mediating an intertribal dispute between the French and Fox. Beset by a new war between the Ojibwe and Dakota in Minnesota and a major confrontation with the Natchez and Chickasaw which closed the lower Mississippi to them, the French bent to the concerns of their allies and reluctantly agreed.

The

French attempt at genocide failed, but it came very close succeeding. Only 500 Fox survived the Fox Wars. After the peace in 1737, the Sac (with the permission of the Iowa) remained west of

the Mississippi until 1743 despite French assurances intended to lure them

back, but the Fox did not return to Wisconsin until 1765, two years after the

French had left North America.

Although

they kept their separate traditions and chiefships, the two tribes afterwards

were bound so close together by their experience that the British and Americans

later had trouble distinguishing between them.

The Fox had suffered severely from the war, so the more-numerous Sac

were the dominant tribe. The close

relationship lasted for more than a century until it nearly dissolved on the

plains of Kansas. The Fox and Sac forgave

most of the tribes which had fought them, but not the Illinois, or the Menominee

and Ojibwe who had attacked the Sac village in 1734.

By

the mid-1700's a large concentration of Indian Nations were located in the

Northwest Territory, generally under

French influence. Other tribes

who wandered into the region drew together under the influence of the

French. In turn, the French supplied

them with arms and relied on these Indian allies to hold back the British

advances.

The

most important French forts, that to some extent controlled the situation, were

at Detroit, Niagara, Mackinac Island, Pittsburgh and Vincennes with a score of

minor posts stretching all the way from New Orleans to Quebec. When France and England were at war in

Europe, the French would lead larger groups of Indian auxiliaries against the

British colonists. The training and

experience turned the Indians into hardened fighters, good marksmen and

geniuses in ambushes and surprise attacks.

Fort Detroit –

1764

formerly Fort Pontchartrain under

the French

(artist conception)

The

French and Indian War, 1754-63, was the final stand the French would take in

the Northwest Territory. A main arena

of combat centered around Lake Champlain and Quebec. Despite the French bringing in a large number of Indian warriors

to aid Montcalm in defending Fort Ticonderoga and other strategic points, the

French lost. When the British took

Quebec, they also acquired all the French territory east of the Mississippi

River.

Generally, when enough of a population had accumulated, then

a frontier policy in clearing out the Redman came into existence. This policy was mainly vocal in nature,

since the frontiersmen relied on the colonial governments to come in and clear

out the Indians for them. Because of

the attitude, many of the pioneers tended to be more vicious than brave,

initiating forceful measures against the tribes with troops and Indian

auxiliaries. The frontiersman's

effectiveness in the field of Indian conquests was not important, but

indirectly, their influence in shaping official policy was something else.

The fissures that opened internally among the tribes from the disruptive influences of these two fronts were spreading throughout the Northwest Territory. The main avenue was the march of white settlements westward that started through the Delaware Confederacy, cracked initially from the Susquehanna crisis. Many of the remnants from the Delaware drifted westward into this region and settled on the upper Ohio River.

Other tribes, that were still intact in this developing

hotbed, sided with the Indian Alliance of the Ottawa leader, Pontiac. In 1763, Pontiac at the head of Indian

forces composed of the following tribes:

Miami, Potawatomi, Shawnee, Ottawa, Ojibwe and the Delaware attacked and

laid siege to the forts at Detroit and Pittsburgh. While in the meantime, settlers were being massacred, towns

burned and a large scale Indian war was being fought in every way.

Though

Pontiac laid siege to the forts, while victorious in other actions against the

English, he failed. His training with

the French earlier was put to good use, but lacking the heavy guns, he was

unable to carry the forts by

assault. After many months of siege

operations the tribes of Pontiac's Alliance disbanded one by one. Pontiac finally gave up the war on the

unkeepable British promises to restrain further settlement in the Territory if

he would demobilize his remaining Indian forces.

The

Northwest Territory was then seized by the English and became part of the

encroaching frontier for the next sixty years.

The Pontiac Wars had succeeded in holding off the British, mainly in the

Detroit region, for about three years.

When Pontiac retired to St. Louis he was murdered by one of his own

race. In the final analysis, he was a

great Indian leader; he stood alone with his race, abandoned by the French,

against the might of England.

By

the late 1760's England secured permission from the Iroquois to expand their

settlements in the Ohio River Valley, occupied by the now shattered

tribes. Land promotion companies were

formed, some getting grants and charters from the Crown. Prices asked by these speculators were so

high that the poor once again took their chances as squatters on tribal

lands. As the influx spread, Indian wars

were once more established.

A

new situation started to develop becoming the most explosive ingredient for

both Red and White worlds. The

emergence of a new nation--the United States of America. From time to time, between 1765 through

1776, the white frontier was tolerated and even abetted by the Indians. After the American Revolution the white

frontier became a major issue all its own.

Indian wars broke out with alarming frequency all over the Northwest

Territory, with secret encouragement from English interests. The Revolution transferred the Indian's

confidence to the English, especially after Washington's government claimed

their lands demanding that they become loyal and keep the peace.

George Washington

1ST President of the United States (1789-1797)

The

British in Canada entertained hopes of eventually recovering the Northwest

Territory. To attain this goal they

encouraged the Indians to resist the American advance. As far as the tribes were concerned, the war

was still on, with the British supplying them with needed firearms and

ammunition.

At the time of the Revolution, portions of the Northwest Territory

were claimed by several of the Thirteen Colonies, through charters and other

land grants. When the Virginia

Legislature organized it's claim in the Ohio Valley, Governor Patrick Henry

outlined the situations and responsibilities that would be encountered by the

new Illinois County Lieutenant-Commandant, John Todd.

Patrick Henry

The following letter

of appointment is the only thing Patrick Henry gave Todd and accounts as one of

the reasons why conditions in the Territory degenerated rapidly into

administrative chaos.

WILLIAMSBURG, DECEMBER 12, 1778

TO MR. JOHN TODD, ESQ.

By

virtue of the act of the General Assembly which establishes the County of

Illinois, you are appointed County Lieutenant-Commandant there, and for the

general tenor of your conduct I refer you to the law.

The

grand objects which are disclosed to your countrymen will prove beneficial, or

otherwise, according to the nature and abilities of that remote country. The present crisis, rendered so favorable by

the good disposition of the French and Indians, may be improved to great

purposes; but if, unhappily, it should be lost, a return of the same attachment

to us may never happen. Considering,

therefore, that costly prejudices are so hard to wear out, you will take care

to cultivate and conciliate the affections of the French and Indians.

Although

great reliance is placed on your prudence in managing the people you are to

reside among, yet, considering you as unacquainted in some degree with their

genius, usages and manners, as well as the geography of that country, I

recommend it to you to advise with the most intelligent and upright persons who

may fall in your way, and to give particular attention to Colonel Clark and his

corps, to whom the State has great obligations. You are to cooperate with him on any military undertaking, when

necessary, and to give the military every aid which the circumstances of the

people will admit of. The inhabitants

of Illinois must not expect settled peace and safety while their and our

enemies have footing at Detroit and can intercept or stop the trade of the

Mississippi. If the English have not

the strength or courage to come to war against us themselves, their practice

has been and will be to have the savages commit murder and depredations. Illinois must expect to pay these a large

price for her freedom, unless the English can be expelled from Detroit. The means for effecting this will not perhaps be in your or Colonel Clark's power,

but the French inhabiting the neighborhood of that place, may be brought to see

it done with indifference, or perhaps join in the enterprise with

pleasure. This is but conjecture. When you are on the spot, you and Colonel

Clark may discover the fallacy or reality of the former appearances. Defense, only, is to be the object of the

latter, or a good prospect of it. I

hope the French and Indians at your disposal will show zeal for the affairs equal

to the benefit to be derived from establishing liberty and permanent peace.

One

great good expected from holding the Illinois is to overawe the Indians from

warring on the settlers on this side of the Ohio. A close attention to the disposition, character and movement of

the hostile tribes is therefore necessary.

The French and militia of Illinois, by being placed on back of them, may

inflict timely chastisement on those enemies whose towns are an easy prey in

the absence of their warriors. You

perceive, by these hints, that something in the military line will be expected

from you. So far as the occasion calls

for assistance of the people composing the militia, it will be necessary to

cooperate with the troops sent from here, and I know of no better general

directions to give than this: that you

consider yourself as the head of the civil department, and as such having

command of the military until ordered out by the civil authority, and to act in

conjunction with them.

You

are, on all occasions, to inoculate on the people the value of liberty, and the

difference between the state of free citizens of this Commonwealth and that

slavery to which the Illinois was destined.

A free and equal representation may be expected by them in a little

time, together with all the improvement in jurisprudence and police which all

other parts of the State enjoy.

It

is necessary, for the happiness, to increase the prosperity of that country,

that the grievances that obstruct those blessings be known, in order to their

removal. Let it therefore be your care

to obtain information on the subject, that proper plans may be formed for the

general utility. Let it be your

constant attention to see that the inhabitants have justice administered to

them for any injury received from the troops.

The omission of this may be fatal.

Colonel Clark has instructions on this head, and will, I doubt not,

exert himself to quell all licentious practices of the soldiers, which, if

unrestrained, will produce the most baneful effect. You will also discontinue and punish every attempt to violate the

property of the Indians, particularly on their land. Our enemies have alarmed them much on that score, but I hope from

your prudence and justice that there will be no grounds of complaint on that

subject. You will embrace every

opportunity to manifest the high regard and friendly sentiments of this

Commonwealth towards all subjects of his Catholic Majesty, for whose safety,

prosperity and advantage you will give every possible advantage. You will make a tender of the friendship and

services of your people to the Spanish Commandant near Kaskaskia, and cultivate

the strictest connection with him and his people. The detail of your duty in the civil department I need not give;

its best direction will be found in your innate love of justice, and the zeal

to be useful to your fellow men. Act

according to the best of your judgement in cases where these instructions are

silent and the laws have not otherwise directed. Discretion is given to you from the necessity of the case, for

your great distance from the government will not permit you to wait for orders

in many cases of great importance. In

your negotiations with the Indians confine the stipulation, as much as

possible, to the single object of obtaining peace with them. Touch not the subject of lands or boundaries

till particular orders are received.

When necessity requires it presents may be made, but be as frugal in

that matter as possible, and let them know that the goods at present is scarce

with us, but we expect soon to trade freely with all the world, and they shall

not want when we can get them.

The

matters given you in charge of being singular in their nature and weighty in

their consequences to the people immediately concerned, and to the whole State,

they require the fullest exertion of your ability and unwearied diligence.

From

matters of general concern you must turn, occasionally, to others of less

consequence. Mr. Roseblove’s wife and

family must not suffer for want of that property of which they were bereft by

our troops. It is to be restored to

them, if possible; if this cannot be done, the public must support them.

I

think it proper for you to send me an express once in the month, with a general

account of affairs with you and any particulars you wish to communicate.

It

is in contemplation to appoint an agent to manage trade on public accounts, to

supply Illinois and the Indians with goods.

If such an appointment takes place, you will give it any possible

aid. The people with you should not

intermit their endeavors to procure supplies on the expectation of this, and

you may act accordingly.

P. Henry (signed)

Congress,

in 1780, took steps that pledged the Original Thirteen States having claims in

the Northwest Territory would give them up.

However certain land tracts were

reserved for special purposes, such as the Military District (Virginia) and the Western Reserve (Connecticut), both were located in modern day Ohio. President Jefferson proposed a plan

of government for this region and Congress later approved it in 1784.

Considered

to be one of the most significant achievements of the Congress of the

Confederation, the Northwest Ordinance

of 1787 put the world on notice not only that the land north of the Ohio

River and east of the Mississippi would be settled but that it would eventually

become part of the United States. Until then this area had been temporarily

forbidden to development.

Increasing

numbers of settlers and land speculators were attracted to what are now the

states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin. This pressure

together with the demand from the Ohio Land Company, soon to obtain vast

holdings in the Northwest, prompted the Congress to pass this Ordinance.

The

area opened up by the Ordinance was based on lines originally laid out in 1784

by Thomas Jefferson in his Report of Government for Western Lands. The

Ordinance provided for the creation of not less than three nor more than five

states. In addition, it contained provisions for the advancement of education,

the maintenance of civil liberties and the exclusion of slavery.

Above

all, the Northwest Ordinance accelerated the westward expansion of the United

States.

The following

excerpted correspondence comes from the military commander of the Northwest

Territory, Brigadier-General Harmar, to the Secretary of War. Harmar had been sent by Congress on an

inspection tour of the Territory, following up complaints of deteriorating

conditions from the settlers. This

letter provides some insight on French, English and Spanish settlements and

addresses itself at length on the current Indian situation.

Brigadier-General

Harmar

TO THE SECRETARY OF WAR

FORT HARMAR, NOVEMBER 24, 1787

Sir;--In my last letter from Post Vincennes, 7 August, after having

published in French and English the Resolve of Congress respecting the

intruders upon the public lands at Post Vincennes, together with my orders

relative thereto, and after having sent messages to the several Indian Chiefs

on the Wabash to assemble at the Post, and hear what I had to say to them, as

there was no probability of these chiefs coming in less than a month, I

informed you that it was my intention to employ that time in visiting

Kaskaskia, in order that I might be enabled to render a statement of affairs in

that part of the United States.

Accordingly,

I marched on the 9th of August, from the Post with a subaltern (Ensign

McDowell) and thirty men, through the prairies, and arrived at Kaskaskia on the

16th of the same month. Our march was

very fatiguing, as the weather was excessively warm and water was very bad and

scarce on our route. I was accompanied

by two Indians--Paoan, a Miami chief and his comrade, who hunted and supplied

the party with meat (buffalo and deer) both on the march and on our return. These prairies are very extensive natural meadows,

covered with long grass. One in

particular which we crossed was eight leagues in breath. They run, in general, north and south, and,

like the ocean, as far as the eye can see, the view is terminated by the

horizon. Here and there a copes of woods

is interspersed. They are free from

bush and underwood, and not the least vestige of their ever having been

cultivated. The country is excellent

for grazing and abounds in buffalo, deer, bear, etc… It is a matter of speculation to account for the prairies. The western side of the Wabash is overflowed

in the spring for several miles.

On

the 17th, I was visited by the magistrates and principal inhabitants of

Kaskaskia, welcoming us on out arrival.

Baptiste du Coigne, the Chief of the Kaskaskia Indians, paid me a visit

in the afternoon, and delivered me a speech, expressive of the greatest

friendship for the United States, and presented me with one of the calumets, or

pipe of peace, which is now sent on.

Some of the Peoria Indians likewise visited me. The Kaskaskia, Peoria, Cahokia and Mitcha

tribes compose the Illinois Indians.

They are almost extinct at present, not exceeding forty or fifty total. Kaskaskia is a handsome little village,

situated on the river of the same name, which empties into the Mississippi at

two leagues from the mouth of the Ohio.

The situation is low and unhealthy, and subject to inundation. The inhabitants are French, and much the

same class as those at Post Vincennes.

Their number is 191, old and young men.

Having

very little time to spare, I left Ensign McDowell with the party at Kaskaskia,

and on the 18th, set out accompanied by Mr. Tardiveau and the gentlemen of the

village, for Cahokia. We gained Prairie

du Rocher, a small village five leagues distant from Kaskaskia, where we halted

for the night. On the 19th we passed

through St. Philp, a trifling village three leagues distant from Prairie du

Rocher, and dined at La Belle Fontaine, six leagues further. La Belle Fontaine is a small stockade,

inhabited altogether by Americans, who have seated themselves there without

authority. It is a bueautiful

situation, fine fertile land, no taxation, and the inhabitants have abundance

to live upon. They were exceedingly

alarmed when I informed them of their precarious state respecting a title to

their possessions, and have now sent on a petition to Congress by Mr.

Tardiveau. On the same day we passed

another small stockade, Grand Ruisseau, inhabited by the same sort of Americans

as those at La Belle Fontaine, and arrived at Cahokia that same evening. Cahokia is a village of nearly the same size

as that of Kaskaskia, and inhabited by the same kind of people. Their number was two hundred and thirty-nine

old men and young. I was received with

the greatest hospitality by the inhabitants.

There was a decent submission and respect in their behavior. Cahokia is distant from Kaskaskia by

twenty-two French leagues, which is about fifty miles.

On

the 21st, in consequence of an invitation from Monsieur Cruzat, the Spanish

Commandant at St. Louis, we crossed the Mississippi, and were very politely

entertained by him. After dinner we

returned to Cahokia. St. Louis

(nicknamed Pancour) is much the handsomest and genteelist village I have seen

on the Mississippi. The inhabitants are

of the same sort as described, excepting that they are more wealthy. About twenty regular Spanish troops are

stationed here. On the 22nd, I left

Cahokia to return to Kaskaskia.

Previous to my departure, at the request of the inhabitants, I assembled

them, and gave them advice to place the militia upon a more respectable footing

than it was, to abide by the decision of the courts, etc… and if there were any

turbulent or refractory persons to put them under guard until Congress should

be pleased to order a government for them.

Exclusive of the intruders already described, there are about thirty

more Americans settled on the rich fertile bottoms on the Mississippi, who are

likewise petitioning by this conveyance.

Brigadier-General Josiah Harmar

On

the 23rd, I passed by the ruins of Fort Chartres, which is one league above

Prairie du Rocher, and situated on the Mississippi. It was built of stone, and must have been a considerable

fortification formerly, but the part next to the river had been washed away by

the floods, and is of no consequence at present. I stayed about a quarter of an hour, but had not the time to view

it minutely, as it was all thicket within.

Several iron pieces of cannon are here at present, and also at the

Indian villages. This evening I

returned to Kaskaskia.

* * * *

*

On

the 27th, I left Kaskaskia, after having received every mark of respect and

attention from the inhabitants, in order to set out for the Post. We marched by a lower route. Several of the French, and the Kaskaskia

chief, with his tribe (about ten in number), accompanied us, and we arrived

safe at Post Vincennes on the afternoon of the 3rd of September. I made the distance by the lower route to be

about one hundred and seventy miles.

On

the 5th, the Plankishaw and Weea Indians arrived at the Post from up the

Wabash, to the number of about one hundred and twenty. Every precaution was taken. We had a fortified camp, two redoubts were

thrown up on our right and left, and the guard in front entrenched. The troops were all new clothed, and made a

truly military appearance. The Indians

saluted us by firing several volleys on the Wabash, opposite our camp. Their salute was returned by a party of our

firing several platoons. I was

determined to impress upon them as much as possible the majesty of the United

States, and at the same time informed that it was the wish of Congress to live

in peace and friendship with them, likewise to let them know that if they

persisted in being hostile that a body of troops would march to their towns and

sweep them off the face of the earth.

On

the 7th, I invited them to camp, and made the enclosed speech, and, in strong

figurative language, they expressed their determination to preserve perfect

peace and friendship with the United States, as long as the waters flowed,

etc… They utterly disavowed any

knowledge of the murder that had been committed, and assured me that inquiry

would be made for the prisoner. They

presented me with a number of calumets and wampum, which I now have the honor

of transmitting, enclosed in a rich otter skin; they will be delivered by Mr.

Coudre. Mr. Coudre has acted as

volunteer for a considerable time in the regiment, and has conducted himself

with propriety. If a vacancy should

happen in the Connecticut quota, I beg leave to recommend him to your notice.

On

the 9th, the young warriors were drinking whiskey and dancing before our tents

all morning, to demonstrate their joy.

On the 10th, I made them presents from the commissioner's goods, to no

great amount.

On

the 12th, the chief part of them left the Post for their different villages up

the Wabash. They returned highly

satisfied with the treatment they received.

Indeed, it was a proper tour of fatigue for me. I found it polite to pay the greatest

attention to them. They are amazingly

fond of whiskey, and destroyed a considerable quantity of it. I trust that you may find this conference

with the Indians attended with very

little expense; I question whether the whole, whiskey, provisions and presents,

will cost the public more than one hundred and fifty dollars. Their interpreter is a half-Frenchman, and

married to a Weea squaw. He has very

great influence among them. I judged it

necessary to pay extraordinary attention to him.

I

have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of several letters from you, which I

shall fully answer by the next conveyance, particularly one of the 2nd of

August, enclosing me a brevet commission of brigadier-general.

After

finishing the conference with the Indians, and obtaining the enclosed petitions

of the inhabitants of Post Vincennes to Congress, relinquishing their charter,

and trusting to that honorable body, I judged it expedite to leave a garrison

at the Post, as it would have been impolitic, after the parade we had made, to

entirely abandon the country.

Accordingly, Major Hantramck commands there. His command consists of Captain Smith's company, fifty-five, and

a part of Fergusion's company, forty; total ninety-five. I have ordered him to fortify himself, and

to regulate the militia, who are to join him in case of hostilities.

Having

arranged all matters to my satisfaction, as we had a long and tiresome voyage

before us, I began to think of winter quarters. Accordingly, on the 1st of October I marched by land with the

well men of Captain Zeigler's and Strong's companies (total: seventy-one), for

the Rapids of the Ohio. I gave orders

to Major Wyllys to command the fleet, and to embark for the rapids the next morning,

with the late Captain Finney's and Mercer's companies, and the sick of the

other companies, and a brass three-pounder.

I omitted mention of my taking into our possession some ordinance and

ammunition (public property) at Louisville and at the Post. At the former we got a brass six-pounder

with swivels; at the latter, from Mr. Dalton, two brass three-pounders. I thought it best that the public property

should be under our own charge.

We

marched along what is called Clarke's Trace, and arrived on the 7th of October

at the Rapids of the Ohio. I was

mistaken, in a former letter, concerning the distance; it is about one hundred

and thirty miles. We saw no sight of

Indians nor signs of Indians.

Little

Turtle, a Miami chief, defeated two American forces, one commanded by Harmar,

with his army composed of regional tribes.

His Indian forces were finally defeated when pitted against the third

American army commanded by General 'Mad' Anthony Wayne at Fallen Timbers. Blue Jacket, a Shawnee, appears to have been

commanding the Indian forces during this engagement. It is an established fact that a number of Canadian English were

fighting with the Indians at Fallen Timbers.

A

long series of land-ceding treaties followed wrung from the Indians between

1794 to 1832. A major Indian stand

against the American encroachment occurred in 1811. The engagement composed of Tecumseh's followers at Prophet's Town

and General Harrison's troops. It was

fought on the west bank of the Tippecanoe River, in modern day Indiana. Though the losses were about equal on both

sides, the Indians were forced to retire from the field of combat and

Tecumseh's vision of a pan-Indian Union

failed to materialize.

The

victories of Wayne, at Fallen Timbers, and Harrison's success at Tippecanoe

prepared the Americans to some extent for the War of 1812. Before the time of Tecumseh, the American

frontier policy had crystallized--'clear

the Indians out !!'

It later became

national policy, thinly disguised behind enforced treaties and there was

virtually no Indian Nation capable to resist that onslaught. The paper storm of these treaties drove the