BACK

BACK

[pp. 263-265]

The tension between the three men in the living room broke suddenly. From upstairs, Dorothea's screams had turned to deep reverberating moans, and through them came the sound of shattering glass. Laporte waved his free hand to his colleague and cried, "Allez, allez!" The man ran for the stairs and began to climb them two at a time. Burger waited, Laporte's hand still restraining him. He figured she'd picked up something and flung it through the window. He hoped that doing so had released some of the terrible tension that had been building in her. He didn't give a damn how much damage she did if it made her feel better. He could have killed this little froggie bastard for driving her half-crazy with his accusations. He must be out of his mind imagining Burger and Dorothea had had anything to do with the little girl's death. What a goddamn mess! How long would it take to convince these cretins?

From upstairs, Laporte's colleague called. His voice was barely audible. Laporte called back to him and he replied in French, "Inspector, quick!"

Burger broke past Laporte and ran upstairs with the inspector a step behind him. He hesitated between the bedroom and the bathroom, then turned for the bedroom. She was lying on her back across the bed with her eyes wide open and Laporte's colleague bent over her. The window had been smashed and glass lay on the carpet and on the bed itself.

Burger picked up her hand. He was trying to figure out if she'd simply fainted. He became aware that her hand was wet, and when he looked at it he saw it was covered in blood. It was a moment before he took in the truth. Even then he couldn't grasp it. She'd taken a sliver of broken glass and slashed both wrists. She still had the long piece of glass in her hand. There was blood all over, now that he began to look around. It trickled down the daggers of glass still attached to the window frame, it stained the carpet, it was soaking into the cream-colored bed cover. But the cops didn't seem to notice. Neither showed any interest in bleeding wrists. They were kneeling on either side of her on the bed looking at her face.

"For Christ's sake, do something!" Burger screamed. He was trying to remember what they'd told him all those years ago when he'd been a Boy Scout. "Isn't there some such thing as pressure points? Some way to stop this bleeding?" he yelled.

"Call the ambulance," Laporte said in French to his colleague.

As the man left the room, Burger saw what it was that Laporte was doing. He'd seized the bottom half of the bed cover and had it tight up against the throat of Dorothea. It was drenched in blood. Blood came through it and around the sides of it and ran over Laporte's hand and over Dorothea's shoulder.

"My God almighty!" Burger whispered, slowly getting to his feet. "What's she done to herself?"

Laporte whispered. "She's severed the--er--carotid artery. I'm afraid. . . ." He shrugged.

"For Christ's sake!" yelled Burger, suddenly. "You're not going to give up on her just like that! We'll get a transfusion! They'll fix her in the hospital! When the paramedics get here . . ."

Laporte shook his head slowly. Burger knew the man was right; it was simply that he didn't want to face the fact. Even as he was looking down at her, he could see the life ebbing from her eyes. Suddenly he couldn't bear to look at her anymore. He bent and took her in his arms and buried his face in the crook of her shoulder. He could feel the warm life trickling out of her onto his cheek and throat. "Oh, my dear, dear Dolly," he sobbed. "Oh, my poor kid. What the Christ have I done to you?"

[pp. 267-268]

After breakfast Uncle David said to Mrs. Davies, "Jennifer, would you feel bad if I went into the village and picked up a paper? It seems criminal to be thinking about the outside world at a time like this, but you know how quickly one gets out of touch. . . ."

"Well, David, of course not," said Mrs. Davies. She got up from the table and began to put the plates from the table onto the bar of the kitchen opening. "There's nothing you can do at the moment. There's nothing any of us can do."

"Keep an eye on . . . ," he whispered confidentially, nodding briefly in Thelma's direction.

"Don't worry," said Mrs. Davies. "It's the top thing on my mind."

[pp. 274-277]

They closed the cellar door and climbed the steps of the veranda. Laporte had his head down and his eyes fixed on the planking of the veranda floor. He was considering the whole case very carefully. When Mrs. Davies opened the door of the villa in answer to the ring of the bell, Laporte gave a little inclination of the head and said gravely, "If you would be so kind, madame. I should like to ask Thelma a few questions."

"Well," said Mrs. Davies, hesitating. Finally she opened the door and let the two policemen in. She said, "If you think it will help. But if you don't mind my staying . . ."

"Of course not," said Inspector Laporte.

Thelma got up from where she had been kneeling in front of the bookcase. "Please, mademoiselle," said Inspector Laporte, removing his cap and indicating a chair.

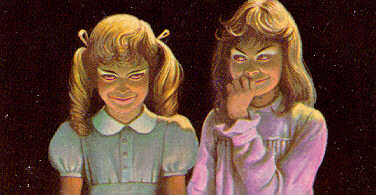

She sat on one of the dining chairs with her legs dangling clear of the floor. She grinned at Inspector Laporte. She kept putting the tip of a finger in her mouth, taking it out when she spoke.

"I am very sorry about your friend, Thelma," said Inspector Laporte. "I think you will help me if you answer some questions. Do you understand?"

Thelma nodded.

"Elizabeth had some photographs in her pocket. Richard says you gave him the film and he made the pictures from it. Is that true?"

Thelma looked at Inspector Laporte. He had pulled up a dining chair and was sitting on it a few feet from her. His hands were resting on his knees and he was looking straight at her. His eyes were very brown. At last she nodded.

"So," said Inspector Laporte. "And you took the pictures with a camera that Mr. Burger had given you for your birthday?"

Thelma nodded.

"Why did you take the pictures?"

Thelma said, "We saw them in the woods."

"But why did you take the pictures of them?"

"She made me," said Thelma.

"Who made you?"

"Elizabeth."

"How did she make you?"

"Twisted my arm," said Thelma.

"How? Can you show me?"

Thelma put one arm behind her back and pushed it up as high as it would go. "Like that," she said.

"And it hurt?"

Thelma nodded.

"So you took the pictures?"

Thelma nodded.

"And then what happened?"

"She stopped twisting my arm," said Thelma.

Mrs. Davies, sitting behind Thelma at the table, looked about to interrupt. Inspector Laporte gave her a quick freezing look and she sat back in her chair, her hands folded over one another on her lap. Inspector Laporte was not going to have a repetition of her behavior when he had first questioned Richard.

"Now, you sent one of the pictures to Mr. Burger with a note demanding one hundred francs. Why did you do that?"

Mrs. Davies stiffened, but she didn't speak.

"She made me. She was going to hurt me again," said Thelma.

"And who collected the money?" said Inspector Laporte.

"Elizabeth," said Thelma.

"Where from?"

"His car."

"Was that where the note said he had to leave it?"

Thelma nodded.

"What did Elizabeth do with the money?"

She kept it.

"All of it?"

"Yes."

"Didn't she give you any of it?" said Inspector Laporte.

"Ten francs," said Thelma.

"And what did you do with it?"

"It was to pay Richard for the other pictures. He wouldn't do them unless I paid him."

"And that is why she gave you the money?"

"To pay Richard," said Thelma.

"So," said Inspector Laporte. "And when you last saw Elizabeth, where did she say she was going?"

"To see Bob."

"Mr. Burger?"

Thelma nodded.

"Why was she going to see him?"

"To get some more money," said Thelma.

"Is that why she had the photographs with her?"

Thelma nodded. "To show him," she said.

"Why didn't you go with her?"

"I didn't want to."

"Why not?"

"I didn't want to."

Inspector Laporte leaned a little closer. "Didn't she say she would hurt you?"

"Yes."

"Well?"

"She tried, but I got away. She didn't catch me."

"And where was she when you last saw her?"

"Going to see Bob," said Thelma.

"I see," said Inspector Laporte. He got up and put on his pillbox hat.

[pp. 279-280]

"Some pictures," said Mrs. Davies. "Some pictures are missing." Her mind was on something else, not Uncle David or what he'd said. She turned to Thelma and asked sharply, "Thelma, what pictures? What were they?"

"Don't you believe me, Mummy?" asked Thelma. There was a little half-concealed sob in her voice.

"Yes, but what pictures did he mean?" Mrs. Davies asked.

Thelma took a handkerchief out of her pocket and began to cry.

"Darling, it's no use . . .," said Mrs. Davies.

"There, there, there," said Uncle David, coming around the table.

Thelma got off the chair and ran to him and put her arms around his waist. She cried, "Uncle David, you believe me, don't you?"

Uncle David bent down and picked her up and she rested her head against his shoulder. "'Course I believe you, darling. 'Course Uncle David believes you."

Mrs. Davies sighed. It was all too much for her. She said, "Thank heavens it's over. I couldn't have stood any more."

"I think you should have a change, Jenny," said Uncle David solicitously. "The starin must have been terrible for you all. I don't think you ought to stay here any longer. We could all go to a nice hotel. Somewhere on the Loire, perhaps? Or we could all go back to London."

[p. 287]

At last he saw it. It was hanging by its straps from the chair by the window. He raced to it and opened it and tipped all its contents on the dressing table.

"You pig!" screamed Thelma, getting up off the bed and running across to him. "Leave that alone! That's my handbag!"

She lunged for the pile of personal treasures on the dressing table, but Richard had recognized the transparent envelope containing the negatives before she could grab it. He picked it up and turned to face her. She was clawing at him like an animal, screaming, "They're mine! Mine! Mine!"

He flung her from him and threw the empty handbag after her. At the door he turned and held up the negatives. "You bitch! You bitch! You bloody awful bitch! If it takes me the rest of my life," he swore, "I'll find some way to prove that you did it."

A moment later, he was racing down the stairs toward the cellar.

PREVIOUS

PREVIOUS

BACK to "Little Sweetheart" page

BACK to "Little Sweetheart" page

File: lsbook09.htm

Updated: February 21, 1999