|

|

|

|

By Vin Kutty

|

|

From a hobbyist’s perspective, pike cichlids of the reticulata group may be divided into two subgroups. The frog-headed ‘Reticulata’ or Batrachops species that occupy slow moving or still water bodies and the bottom-hopping rheophilic species like Crenicichla jegui. I call the latter 'Jegui' group species. This segregation is not taxonomically valid since the differences between these two unofficial groups have not been verified. However, each group is sufficiently different in their husbandry requirements that separating them here for aquaristic purposes feels justified. For the purposes of this article, the frog-headed Batrachops will be considered a subgroup of the official reticulata group.

The business end of a Crenicichla jegui. V. Kutty Photo 2001.

Reticulata group (17 species) |

cametana, Steindachner 1911 |

There are four described species of ‘Batrachops’. C. reticulata (Heckel, 1840) and C. semifasciata (Heckel, 1840) were the first to be described, followed by C. cyanonotus Cope, 1870 and very recently, C. stocki Ploeg, 1991. All of these species have been imported into North America but the most common species encountered is C. semifasciata. Of course, common here is a relative term, as I have only seen this species being offered for sale a couple of times in the last ten to fifteen years. C. stocki was the subject of export during the early 1990s when collectors and exporters in Brazil were trying to decipher the tastes of hobbyists, as the sudden spike in interest in East Brazilian clear water Loricariids and the Orange Pike (C. sp. Xingu 1) failed to transfer to other species from the area. As a result of this trade experiment, I was the lucky recipient of three reticulata group species during 1993 namely, C. stocki, C. cametana and C. cyclostoma. I have not seen any of these species offered for sale since. C. reticulata is one of the most widely distributed cichlid species in Amazonia but still, their occurrence in the hobby is extremely rare at best. C. cyanonotus and the undescribed Peruvian and Bolivian species are the rarest of all.

C. semifasciata is the southernmost representative of the group, distributed in the Rio Paraguay drainage of Brazil, Paraguay and Northern Argentina. Most recently, this species has been exported from the Argentine province of Formosa, the next planned stop of my exploration of the southern cone of the continent. Here, it is found along with Bujurquina vittata, Crenicichla lepidota, Laetacara dorsiger, Apistogramma trifasciata and some undescribed Apistogramma currently called A. sp. Paraguay. This species looks more like a frog than the other three, with its short snout and wide head. When viewed from above, adults look like microphones, with circular head and gradually tapering body.

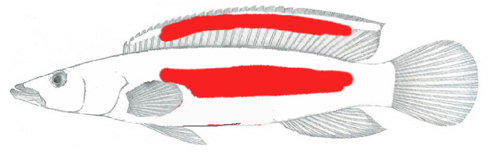

Crenicichla semifasciata female in breeding colors. V. Kutty Photo 1995.

The sexes are difficult to distinguish when young, but after they reach 4 to 5 inches TL, males develop spots on the posterior part of the soft dorsal fin, just above the caudal fin. Females develop a bright red band on the dorsal fin when sexually mature with a fainter red band running along the longitudinal line. The red coloration, the onset of which is often mood or hierarchy dependent, is independent of the presence of males and appears seasonally, possibly signaling the seasonal dependence of their reproduction in the wild. This pattern of red coloration on the females and dorsal fin spotting on the males is common to all four Batrachops species and may be reliably used to distinguish the sexes.

Females of the lowland quiet water species show seasonal red breeding coloration as shown here.

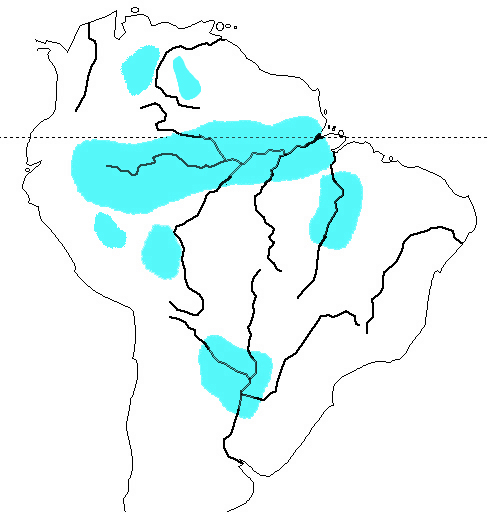

Distribution of Crenicichla reticulata group species

As for aquarium manners, none of them are model citizens. They are highly territorial, more so than pikes of the saxatilis or lugubris group. They are particularly fond of driftwood with large holes or caves, which they constantly occupy and will defend, sometimes even against humans. Wild C. reticulata were caught by the dozens, when my friend, Jeff Cardwell and I were throwing cast nests against a river bank filled with “Pleco holes” in Rio Uatuma, a whitewater, left bank tributary of the Amazon, a few hundred miles down stream of Manaus. This was a piranha-infested river and these pikes were occupying holes dug in the soft ground previously used by large Loricariid catfish. The vibration of the lead weights hitting the mud scared them into our nets. Tucked away from each other’s sight, we caught many full-grown adults residing within inches of each other. This behavior was previously unrecorded. The water there was soft with a pH of 6.4. Back home, the same fish tucked away in caves can be seen flaring their gill covers at passersby, be they piscine, canine or human. I tried to breed these fish for four years, even taking them with me when I moved my residence from Florida to California, all to no avail. Aggression finally diminished their numbers to two females, whom I had to keep separated. Accepting reality, I finally gave them away.

Undescribed species from the Guapore Basin. Jeff and I caught just one of these fish in Rio San Martin, Beni, Bolivia.

Very little is known about C. cyanonotus. From the scant records of observations of C. cyanonotus, it appears this species is more variable than others in this subgroup. C. cyanonotus also display a marked difference in the sizes of the sexes, with the females remaining much smaller than the males. This species has been reported to occur only along the Rio Amazonas. Warzel (1994) reports an aquarium spawning of this species and typical to all pikes, they are cave spawners.

Batrachops species do not have humeral ocelli (shoulder spot), but there is a Batrachops species reported from the Upper Rio Tapajos with a shoulder spot. This has not been confirmed but the upper reaches of the southern clear water tributaries of the Amazon have not been well explored and probably hold many unknown pikes.

The Rheophilic Jegui Group

The second subgroup of the reticulata group is rheophilic, specialized species. As stated above, for merely illustrating the different husbandry requirements of these pikes from those of the Batrachops group, I have separated them and will collectively address them as ‘jegui-group’ here.

This group contains the most commonly available species of reticulata group, Crenicichla sp. “Belly Crawler”, also sold as Green Hopper Pike or C. sp. Belly Slider or C. sedentaria. The common name of this species gives away the fact that this is a bottom bound fish with celestially pointed eyes. It is frequently collected in the upper Rio Meta drainage, around the town of Villavicencio, Colombia and exported to all takers, along with juveniles of C. sp. Venezuela (sp. Orinoco), an undescribed lugubris group species and occasionally also Crenicichla sveni, a spangled pike. C. sp. Belly Crawler has been exported and incorrectly sold as C. sedentaria because of its lethargic, sedentary lifestyle, but C. sedentaria is a similar but distinct pike from rapids of Rio Chinipo in Central Peru, separated from C. sp. Belly Crawler in distribution by over a thousand miles. A similar but never-exported species is found in Rio Caura in Venezuela. It is similar in shape and size to C. sp. Belly Crawler, but the barring on the flanks and the suborbital stripe are more prominent and contrasting. The Field Museum in Chicago has conducted a Rapid Assessment Program of Rio Caura and ichthyofauna seems fascinating.

Remember that this and the rest of the pikes discussed in the remainder of this article hail from highly oxygenated, moving waters and require similarly high oxygen levels in captivity. They don’t seem to miss the water current of their birthplace as they don’t seem to particularly enjoy being in front of a powerhead or a filter return spout. Also, their adaptation to rapids and fast-flowing streams seems to have evolved away fully functional swim bladders. Some, like C. cametana and C. cyclostoma are more adept at swimming while C. jegui is a poor swimmer but is capable of making sprints and dashes in pursuit if prey; C. sp. aff. jegui is a notoriously poor swimmer that relies almost entirely on camouflage and is almost incapable of chasing after its prey. I find it fascinating that Crenicichla has members who have sacrificed their ability to move in favor of camouflage while others like C. missioneira of Rio Uruguay, are such rapid sprinters that their chasing behavior in aquaria is almost too fast for the human eye to observe.

Crenicichla jegui. V. Kutty Photo 2001.

Moving further east, there are no known rheophilic members of the reticulata group until you reach Rio Tocantins and its major tributary Rio Araguaia, where you are rewarded with dorsally compressed C. cametana, C. jegui, C. sp. aff. jegui and the laterally compressed C. cyclostoma. The first two species have not been exported regularly in many years while C. jegui and C. sp. aff jegui are seen or heard of occasionally. Shipments of these fish from Brazil to Japan or Germany may be intercepted at “trans-shippers” if you are lucky and know the right people – but be prepared to pay a mortgage-like sum to acquire a small colony.

Crenicichla stocki male

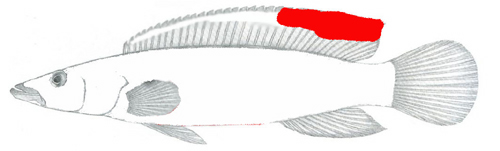

An undescribed species similar to C. jegui

There has been some confusion regarding the C. jegui and C. sp. aff jegui. The following tips may be helpful in distinguishing the two sibling species. C. jegui, when viewed from above have a very elongated, pointed snout whereas C. sp. aff jegui have a shorter, wider, massive, bulldog-type head and body. C. jegui has a gray background color while the 'Bulldog Pike' has a creamy-brown base color. C. jegui have spots and hardly any blotches or bands on the head while the ‘Bulldog Pikes’ have some spots but a lot more blotches on the face and body. Neither species has a developed swim bladder but the Bulldog pike is even clumsier. My C. jegui could sprint to snatch up goldfish easily but the undescribed Bulldog Pike is certainly no sprinter, it can only snatch up goldfish within a few inches of its face. C. jegui do not dig. C. sp. aff jegui dig a lot. C. jegui makes an appearance once a year or so somewhere. C. sp. aff. jegui makes an appearance once or twice a decade and costs a lot more.

Females of the rheophilic species show seasonal red flag on the soft dorsal.

The species I’ve covered here in my fifth installment of Crenicichla articles are neither colorful nor easily obtained, but are fascinating in their behavior and highly specialized feeding habits. Any advanced hobbyist with a large aquarium will thoroughly enjoy keeping them.

|

References

HECKEL, J. 1840. Johann Natterer's neue Flussfische Brasilien's nach den Beobachtungen und Mittheilungen des Entdeckers beschrieben. (Erste Abtheilung, die Labroiden.) Annln wien. Mus. Natges. 2: 327-470. KULLANDER, S.O. & H. NIJSSEN. 1989. The cichlids of Surinam. E.J. Brill, Leiden and other cities. KULLANDER, S.O. 1981b. Cichlid fishes from the La Plata basin. Part I. Collections from Paraguay in the Museum d'Histoire naturelle de Geneve. Revue suisse Zool. 88: 675-692. KULLANDER, S.O. 1982. Cichlid fishes from the La Plata basin. Part III. The Crenicichla lepidota species group. Revue suisse Zool. 89: 627-661. KULLANDER, S.O. 1986. Cichlid fishes of the Amazon River drainage of Peru. Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm. PLOEG, A. 1986. The fishes of the cichlid genus Crenicichla in French Guiana. Bijdr. Dierk. 56: 221-231. PLOEG, A. 1987. Review of the cichlid genus Crenicichla Heckel, 1840 from Surinam, with descriptions of three new species. Beaufortia 37: 73-98. PLOEG, A. 1991. Revision of the South American cichlid genus Crenicichla Heckel, 1840, with descriptions of fifteen new species and considerations on species groups, phylogeny and biogeography. Academisch Proefschrift, Universiteit van Amsterdam. Thesis. REGAN, C.T. 1905. A revision of the fishes of the South-American cichlid genera Crenacara, Batrachops, and Crenicichla. Proc. zool. Soc. Lond. 1905: 152-168. REGAN, C.T. 1913. A synopsis of the cichlid fishes of the genus Crenicichla. Ann. Mag. nat. Hist. (8) 11: 498-540. Warzel, F. 1994. Remarks on some species of the Crenicichla reticulata group. Cichlid Yearbook 4. Cichlid Press.

|

| Back to ==> Home / Pike Cichlid Articles / Froghead Pikes |

| Home | Pikes | Neotropicals | Collecting | Photography | Personal | Links | Site map |

|

http://geocities.datacellar.net/NapaValley/5491

Latest update: 19 Aug 2006 Comments on this page: email me at vin dot kutty at gmail dot com |