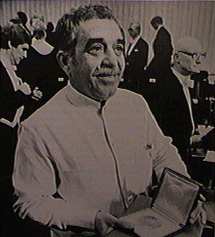

Gabriel García Márquez (III)

Discurso del Premio Nobel

(en Inglés)

The Solitude of Latin America

Gabriel García Márquez

Nobel Prize Lecture, 8 December 1982

Antonio Pigafetta, a Florentine navigator who went with Magellan on the

first voyage around the world, wrote, upon his passage through our southern lands of

America, a strictly accurate account that nonetheless resembles a venture into fantasy. In

it he recorded that he had seen hogs with navels on their haunches, clawless birds whose

hens laid eggs on the backs of their mates, and others still, resembling tongueless

pelicans, with beaks like spoons. He wrote of having seen a misbegotten creature with the

head and ears of a mule, a camel's body, the legs of a deer and the whinny of a horse. He

described how the first native encountered in Patagonia was confronted with a mirror,

whereupon that impassioned giant lost his senses to the terror of his own image.

This short and fascinating book, which even then

contained the seeds of our present-day novels, is by no means the most staggering account

of our reality in that age. The Chronicles of the Indies left us countless others.

Eldorado, our so avidly sought and illusory land, appeared on numerous maps for many a

long year, shifting its place and form to suit the fantasy of cartographers. In his search

for the fountain of eternal youth, the mythical Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca explored the

north of Mexico for eight years, in a deluded expedition whose members devoured each other

and only five of whom returned, of the six hundred who had undertaken it. One of the many

unfathomed mysteries of that age is that of the eleven thousand mules, each loaded with

one hundred pounds of gold, that left Cuzco one day to pay the ransom of Atahualpa and

never reached their destination. Subsequently, in colonial times, hens were sold in

Cartagena de Indias, that had been raised on alluvial land and whose gizzards contained

tiny lumps of gold. One founder's lust for gold beset us until recently. As late as the

last century, a German mission appointed to study the construction of an interoceanic

railroad across the Isthmus of Panama concluded that the project was feasible on one

condition: that the rails not be made of iron, which was scarce in the region, but of

gold.

Our independence from Spanish domination did not put

us beyond the reach of madness. General Antonio López de Santana, three times dictator of

Mexico, held a magnificent funeral for the right leg he had lost in the so-called Pastry

War. General Gabriel García Moreno ruled Ecuador for sixteen years as an absolute

monarch; at his wake, the corpse was seated on the presidential chair, decked out in

full-dress uniform and a protective layer of medals. General Maximiliano Hernández

Martínez, the theosophical despot of El Salvador who had thirty thousand peasants

slaughtered in a savage massacre, invented a pendulum to detect poison in his food, and

had streetlamps draped in red paper to defeat an epidemic of scarlet fever. The statue to

General Francisco Moraz´n erected in the main square of Tegucigalpa is actually one of

Marshal Ney, purchased at a Paris warehouse of second-hand sculptures.

Eleven years ago, the Chilean Pablo Neruda, one of the outstanding poets

of our time, enlightened this audience with his word. Since then, the Europeans of good

will--and sometimes those of bad, as well--have been struck, with ever greater force, by

the unearthly tidings of Latin America, that boundless realm of haunted men and historic

women, whose unending obstinacy blurs into legend. We have not had a moment's rest. A

promethean president, entrenched in his burning palace, died fighting an entire army,

alone; and two suspicious airplane accidents, yet to be explained, cut short the life of

another great-hearted president and that of a democratic soldier who had revived the

dignity of his people. There have been five wars and seventeen military coups; there

emerged a diabolic dictator who is carrying out, in God's name, the first Latin American

ethnocide of our time. In the meantime, twenty million Latin American children died before

the age of one--more than have been born in Europe since 1970. Those missing because of

repression number nearly one hundred and twenty thousand, which is as if no one could

account for all the inhabitants of Uppsala. Numerous women arrested while pregnant have

given birth in Argentine prisons, yet nobody knows the whereabouts and identity of their

children who were furtively adopted or sent to an orphanage by order of the military

authorities. Because they tried to change this state of things, nearly two hundred

thousand men and women have died throughout the continent, and over one hundred thousand

have lost their lives in three small and ill-fated countries of Central America:

Nicaragua, El Salvador and Guatemala. If this had happened in the United States, the

corresponding figure would be that of one million six hundred thousand violent deaths in

four years.

One million people have fled Chile, a country with a

tradition of hospitality--that is, ten per cent of its population. Uruguay, a tiny nation

of two and a half million inhabitants which considered itself the continent's most

civilized country, has lost to exile one out of every five citizens. Since 1979, the civil

war in El Salvador has produced almost one refugee every twenty minutes. The country that

could be formed of all the exiles and forced emigrants of Latin America would have a

population larger than that of Norway.

I dare to think that it is this outsized reality, and

not just its literary expression, that has deserved the attention of the Swedish Academy

of Letters. A reality not of paper, but one that lives within us and determines each

instant of our countless daily deaths, and that nourishes a source of insatiable

creativity, full of sorrow and beauty, of which this roving and nostalgic Colombian is but

one cipher more, singled out by fortune. Poets and beggars, musicians and prophets,

warriors and scoundrels, all creatures of that unbridled reality, we have had to ask but

little of imagination, for our crucial problem has been a lack of conventional means to

render our lives believable. This, my friends, is the crux of our solitude.

And if these difficulties, whose essence we share,

hinder us, it is understandable that the rational talents on this side of the world,

exalted in the contemplation of their own cultures, should have found themselves without

valid means to interpret us. It is only natural that they insist on measuring us with the

yardstick that they use for themselves, forgetting that the ravages of life are not the

same for all, and that the quest of our own identity is just as arduous and bloody for us

as it was for them. The interpretation of our reality through patterns not our own, serves

only to make us ever more unknown, ever less free, ever more solitary. Venerable Europe

would perhaps be more perceptive if it tried to see us in its own past. If only it

recalled that London took three hundred years to build its first city wall, and three

hundred years more to acquire a bishop; that Rome labored in a gloom of uncertainty for

twenty centuries, until an Etruscan King anchored it in history; and that the peaceful

Swiss of today, who feast us with their mild cheeses and apathetic watches, bloodied

Europe as soldiers of fortune, as late as the Sixteenth Century. Even at the height of the

Renaissance, twelve thousand lansquenets in the pay of the imperial armies sacked and

devastated Rome and put eight thousand of its inhabitants to the sword.

I do not mean to embody the illusions of Tonio

Kröger, whose dreams of uniting a chaste north to a passionate south were exalted here,

fifty-three years ago, by Thomas Mann. But I do believe that those clear-sighted Europeans

who struggle, here as well, for a more just and humane homeland, could help us far better

if they reconsidered their way of seeing us. Solidarity with our dreams will not make us

feel less alone, as long as it is not translated into concrete acts of legitimate support

for all the peoples that assume the illusion of having a life of their own in the

distribution of the world.

Latin America neither wants, nor has any reason, to

be a pawn without a will of its own; nor is it merely wishful thinking that its quest for

independence and originality should become a Western aspiration. However, the navigational

advances that have narrowed such distances between our Americas and Europe seem,

conversely, to have accentuated our cultural remoteness. Why is the originality so readily

granted us in literature so mistrustfully denied us in our difficult attempts at social

change? Why think that the social justice sought by progressive Europeans for their own

countries cannot also be a goal for Latin America, with different methods for dissimilar

conditions? No: the immeasurable violence and pain of our history are the result of

age-old inequities and untold bitterness, and not a conspiracy plotted three thousand

leagues from our home. But many European leaders and thinkers have thought so, with the

childishness of old-timers who have forgotten the fruitful excess of their youth as if it

were impossible to find another destiny than to live at the mercy of the two great masters

of the world. This, my friends, is the very scale of our solitude.

In spite of this, to oppression, plundering and

abandonment, we respond with life. Neither floods nor plagues, famines nor cataclysms, nor

even the eternal wars of century upon century, have been able to subdue the persistent

advantage of life over death. An advantage that grows and quickens: every year, there are

seventy-four million more births than deaths, a sufficient number of new lives to

multiply, each year, the population of New York sevenfold. Most of these births occur in

the countries of least resources-- including, of course, those of Latin America.

Conversely, the most prosperous countries have succeeded in accumulating powers of

destruction such as to annihilate, a hundred times over, not only all the human beings

that have existed to this day, but also the totality of all living beings that have ever

drawn breath on this planet of misfortune.

On a day like today, my master William Faulkner said, "I decline to accept the end of man". I would fall unworthy of standing in this place that was his, if I were not fully aware that the colossal tragedy he refused to recognize thirty-two years ago is now, for the first time since the beginning of humanity, nothing more than a simple scientific possiblity. Faced with this awesome reality that must have seemed a mere utopia through all of human time, we, the inventors of tales, who will believe anything, feel entitled to believe that it is not yet too late to engage in the creation of the opposite utopia. A new and sweeping utopia of life, where no one will be able to decide for others how they die, where love will prove true and happiness be possible, and where the races condemned to one hundred years of solitude will have, at last and forever, a second opportunity on earth.