by Michael David Coffey

Sergey Yesenin, 1922

I don't pity, don't call, don't cry

My heart, touched by the chill within,

You will not beat as before,

And the cotton birches of the countryside

No more will lure me to gad about barefoot.

From 'I don't pity, don't call,...' 1921

Translated by Lyuba Coffey

Sergey Yesenin, c. 1919

Sergey Yesenin is without doubt the most profoundly Russian of all the poets of the Revolution. Sometimes dismissed by elitist poetic circles as a 'peasant poet', Yesenin was in fact an extremely gifted lyricist, an intellectual and a celebrity. He was the poet of the people, not only during the early days of the Revolution but long after his death in 1925 at age 30. His poetry survived through the Stalinist period, despite official disapproval of his works. His little books of poetry, often in tatters, could be found in the hands of migrant workers and Red Army soldiers. Many of his poems are learnt by heart at school. They have been set to music and are popular songs in modern Russia. His poetry, deceptively simple in structure, is fresh, sincere, melancholy and full of fire.

Yesenin in 1915

I do not regret the years squandered in vain,

I do not regret the lilac blossom within my soul.

In the garden, a fire of rowan-berries is burning,

But it cannot warm anyone.

The rowan-berries in clusters, will not be scorched,

The grass will not grow yellow and perish.

As the tree gently lets fall its leaves,

So I let fall melancholy words.

From 'The golden grove has ceased to speak...' 1924

Translated by Dimitri Obolensky

Now my youth has roared out,

Not everyone has his soulmate,

Once more the years fly out the shadows

And like meadows of daisies they are rustling.

I dreamt today of my dog,

That was my friend in youth.

Like out the rotten maple beneath my window,

But I still remember the girl in white,

For whom the dog was a postman.

But she was like a song to me,

Because she never took from the dog's collar

Any of the notes I wrote.

From 'Son of a Bitch' 1924

Translated by Lyuba Coffey

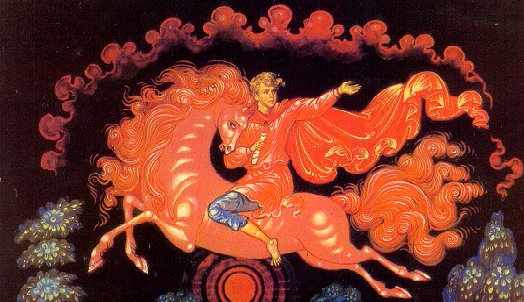

He was a striking figure with his blonde hair like fields of rye, sparkling cornflower blue eyes, beautiful looks and a deep resonant voice. Donned in his blue peasant blouse, with golden silk cord, he attracted huge admiring audiences wherever he traveled in Russia. Chanting poems about the countryside, sweet Jesus, horses, clouds, revolutions, love and melancholic lanscapes... He all but sang the verses, and mesmorized his adoring audience with his passion and artistry. In his earlier poetry, the horse occupied a central theme. In fact, Yesenin envisioned himself as a foal maddened by the fire-breathing locomotive of industrialization. And running ackwardly beside --

Have you seen the locomotive

On its cast-iron hoofs

Charge across the countryside

Dodging in and out the mists

Hissing by the lake through its nostrils of iron?

As in some desperate race

On an evergreen gymkhana course --

Springing through the high grass,

Its slender legs flung out too far,

A foal with a red mane?

From 'Prayer for the First Forty Days of the Dead' 1920

Translated by Rose Styron

Born on October 3, 1895 in Kostantinovo (now Yesinino) in the province of Ryazan in Central Russia, his parents soon moved to the city, leaving him in the care of his grandparents, who were devout Christians of the old faith(Old Believers). 'I remember the forest, the wide, deeply rutted road. I am with you grandmother, on the way to Radovetsky Monastery, some forty versts away.' Yesenin was a high spirited village boy full of mischief. His early poetry is about the sunsets, the animals,... the forests.

That's the dark blue clang her horseshoes make.

Wind, a monk, walks past with wary footsteps

Holding back the foliage on the pathways,

Kissing, when he comes upon the mountain ash,

Crimson wounds that are the marks of Christ unseen.

From 'Autumn' 1914

Translated by Evelyn Bristol

And there stands the birch tree

In a sleepy silence,

And there burn the snowflakes

In the golden fire.

And the dawn, lazily

Going round,

And scatters the branches

With new silver..

From 'The Birch Tree' 1913

Translated by Lyuba Coffey

You, yourself, under the rain of my caresses will caste off your silk train,

And I'll carry you, lightheaded, to the bush till morning.

And let the woodgrouse cry with ringing.

There is some merry melancholy in the scarlet of dawn..

From 'The Scarlet of the Dawn' 1910

Translated by Lyuba Coffey

Zinaida Nikolayevna Riykh

Yesenin was married five times in his short but very full life. His first marriage was to Anna Romanovna Izryadnova in 1913. They had a son Yuri in 1914. The second was to Zinaida Nikolayevna Riykh, an actress, in 1918. She bore him a daughter Tatiana and a son Konstania the following year. A year later they separated and he began the life of a wandering Bohemian poet. He was divorced from Riykh in October 1921 at the time when he first became acquainted with Isadora Duncan, the famous American dancer. In 1922 they were married and sailed for America on the 'Paris'. He was suspected of being a subversive and was held briefly on Ellis Island with his wife. The short stormy marriage was all the more remarkable, not that he was 17 years younger, but because he spoke no English and she no Russian. Traveling with her on dance tours, he acted the role of the hooligan in the most fashionable hotels and restaurants in America and Europe. A year later, in 1923, they were separated. Next there was a civil marriage to Galina Arturovna Benislavskaya, his secretary. Also in that same year he had a son Alexandr by the poet Nadezhda Davidnova Volpin. Yesenin never saw Alexandr. Ironically, Alexandr Sergevich Volpin-Yesenin later became a well known poet in the dissident movement in Russia in the 1960s. In March 1925, Yesenin became acquainted with the grandaughter of Leo Tolstoi, Sophia Andreyevna Tolstoya. She became his last wife.

Isadora Duncan

and Yesenin, 1922

I am still the same.

In my heart I am still the same.

Like cornflowers in the rye, my eyes bloom in my face.

Spreading like golden mats, my poems,

I wish to relate tender thoughts to you.

Good night!

Good night to you all!

The scythe of the twilight's dawn has sung out

Today I very much want to piss

The moon from the window.

From 'Hooligan's Confession' 1920

Translated by Lyuba Coffey

The last two years of his life were marked by wild extremes of debauchery and heavy drinking. Despite these excesses, he wrote prolifically and his life is vividly recorded in the last poems. He traveled south to the Caucasus, where he seemed to recover from his melancholy. He met Shagane (Shagandukht Nersesovna Talyan), my Shagi, and began a cycle of love poems: Persian Motifs. In them he longs for that perfect love, of roses and the nightingale's song.

My darling's hands -- a pair of swans --

Are diving in the gold of my hair.

Everybody, the people of this world

Sing the song of love, endlessly.

So did I, sometime, long ago

And now I'm singing the same, again,

That is why my words are steeped in tenderness

Are breathing deeply.

If the soul is loved to the depths,

The heart will become a golden block,

Only the Tegeran moon

Will not warm the song.

I don't know how I can live my life:

Shall I burn in the sweet caresses of the sweet Shagi

Or shall I anxiously grieve

Over the distant memory of a brave song?

From 'My darling's hands...' August 1925

Translated by Lyuba Coffey

.

My Shagane!

You said that Sa'adi

From 'You said that Sa'adi...' 1924

Translated by Lyuba Coffey

The momentary window of new hope was soon vanquished. In late December 1925, after spending some weeks in a mental hospital, he was found hanged with a strap from his suitcase in his room in the Hotel Angleterre in St. Petersburg. The previous day he had torn a page with a poem from his book and given this to his friend Erlikh but asked him not to read it in his presence. Erlikh read it on December 28, the day Yesenin died. It was a poem written in his own blood:

Goodbye: no handshake to endure.

Let's have no sadness -- furrowed brow.

There's nothing new in dying now

Though living is no newer.

'Goodbye, My Friend...'

Translated by Geoffrey Hurley

Alexandr Voronsky (1884-1937), a political writer and philosopher, had tried to intervene and help Yesenin have his alcoholism treated. In his 'In Memory of Yesenin (Reminiscences)' in 'Art as a Cognition of Life' published in 1926, Voronsky provides some insight into the temperament and character of this most enigmatic of poets. He recounts the strange duality of his personality. On the one hand, he was polite, calm, restrained, reasonable and distant. On the other, he was arrogant, boastful and rude. He describes an instance, where Yesenin, extremely drunk, climbed on a chair and began an incoherent, boastful speech. But then a little later, he recited his poetry from memory... It was masterful, hypnotizing. Yesenin was one of the best at reciting poetry in all of Russia. The poems came from his very core, and any excesses came from his heart.

Voronsky describes Yesenin's preparations for his return to Baku in the Spring of 1925. The poet talked about his return to 'Persia', to the gardens of Shiraz to breathe in the air which the great Sa'adi had breathed. 'Everything about him seemed to be doomed and looked absolutely superfluous here. For the first time I felt surely that he didn't have long to live and that his fire was dying out.'

Ah friend, my friend,

How sick I am. Now do I know

Whence came this sickness.

Either the wind whistles

Over the desolate unpeopled field,

Or as September strips copse,

Alcohol strips my brain.

The night is freezing

Still peace at the crossroads.

I am alone at the window,

Expecting neither visitor nor friend.

The whole plain is covered

With soft quick-lime,

And the trees, like riders,

Assembled in our garden.

Somewhere a night bird,

Ill-omened, is sobbing.

The wooden riders

Scatter hoofbeats.

And again the black

Man is sitting in my chair,

He lifts his top hat

And, casual, takes off his cape.

From 'The Black Man'

Translated by Geoffrey Hurley

Yesenin's 'simplicity', the songlike qualities, sincerity and lyricisms are all reflected vividly in his poetry. They imbue his personal psyche. He called his poems about animals 'a paean to animal rights'. His melancholic imagery in the poem about the red-maned colt is a stark prophecy concerning today's dehumanized, urban society. The death of Yesenin, the most Russian of poets, marked the end of the Bolshevik regime's tolerance of artistic freedom. But his legacy traveled well in the sacks of migrant workers and Red Army soldiers, through all the years of the Soviet Russia. And his voice rang out in the lyrics of popular tunes all over his beloved 'Rus'. His verses about folklore, themselves became folklore.

Dear foolish little colt!

Where, why does he race?

Hasn't he heard that cavalries

Of steel have conquered live steeds

And all his chasing, galloping,

Over the sad plain

Cannot catch those days gone by

When Pechenegs would barter

A pair of lovely Russian girls

Of the steppes for a single horse?

Fate in the marketplace has changed?

From 'Prayer for the First Forty Days of the Dead' 1920

Translated by Rose Styron

Chronology