A Record Rescue?

by RAdm. Joseph M. Worthington, USN (Ret.)

ON THE MORNING OF JUNE 4, 1942 I was in command of the United States Destroyer BENHAM DD-397, 1,500 tons, stationed in the screen of the carriers ENTERPRISE and HORNET. Our aircraft were then engaged in intensive offensive operations against the large Japanese forces approaching Midway. Shortly after noon, orders were received from our task force commander, Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, to join the heavy cruisers PENSACOLA and VINCENNES and the destroyer squadron flagship BALCH, and to proceed at maximum speed to reinforce the cruiser-destroyer screen of the aircraft carrier YORKTOWN, which was under heavy attack by Japanese carrier aircraft. Our small group had no sooner started in the direction of the YORKTOWN task force than we sighted dead ahead a huge column of smoke over the horizon, which was pouring skyward from YORKTOWN'S first battle damage of the day.

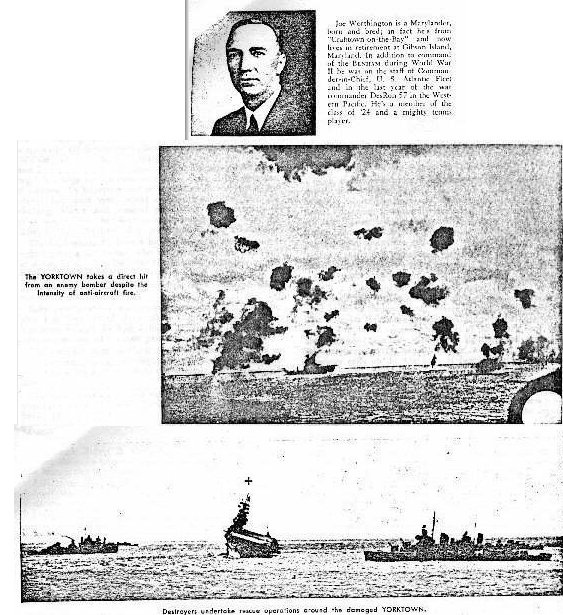

After joining, about 1335, the YORKTOWN task force which had stopped while repairs were being made to the carrier, our ships took their stations in the screen, and as soon as possible all ships increased speed to the maximum the damaged carrier could attain, at first 5 knots, but 17 knots by the time that the Japanese torpedo attack reached the launch point.

At about 1432 the planes had been reported approaching the formation from a radar bearing 200 degrees true distant 30 Miles, and about three minutes later BENHAM opened fire on the enemy planes at maximum range bearing 270 degrees. The torpedo planes flew so low that they appeared to be dipping between the masts of the ships in the screen. Every anti-aircraft gun in the task force which could be brought to bear was firing on the attacking planes. Some cruiser eightinch guns were also firing into the sea in advance of the torpedo planes in the hope that the shell splashes would interferc with the accuracy of the torpedo fire. During this attack Ensign Walter E. Pierce of BENHAM was mortally wounded and four others also were wounded by fragments of an anti-aircraft shell which struck the stack, and severely damaged our only lifeboat. All the enemy planes were shot down, most of them by anti-aircraft fire from our ships. I remember radically maneuvering the BENHAM to avoid being struck by falling flaming planes which hit the water close aboard. Some flaming aircraft narrowly missed other vessels in the screen as they crashed into the sea. The BENHAM was credited with assisting in shooting down five planes. Nevertheless, two torpedoes struck the YORKTOWN, and she quickly took a list toward the damaged side.

That famous aircraft carrier had been structurally weakened by battle damage in the Coral Sea engagement, and had had only hurried twenty-four-hour emergency repairs at Pearl Harbor enroutc to Midway. She had already sustained bomb hits from enemy carrier planes in the first attack of the day and she now received severe underwater damage from torpedoes. Extensive damage control measures were attempted, but the ship lay dead in the water, and took a severe list, which steadily increased from progressive flooding. Capsizing appcarcd likely, another air attack was immincnt, and enemy submarines were known to be present in the area; the order was given to abandon ship.

About 1500, 4 June the officers and men of the YORKTOWN Climbed down cargo nets and ropes and slid into the sea, while several destroyers closed in to effect the rescue of some 2,300 men in the water. Life rafts were dropped into the ocean by all the ships in the vicinity. The one damaged lifeboat of the BENHAM was launched immediately and did splendid service both in rescuing personnel from the sea, and in towing heavily loaded life rafts to the destroyer. One near tragedy occurred when another air attack was reported. The destroyers were ordered to cease rescue operations, and resume their anti-aircraft stations in the screen of the now crippled carrier, which still lay dead in the water. The BENHAM interrupted rescue operations momentarily. But her position near the stern of the carrier, in the middle of hundreds of men close aboard awaiting rescue, made it impossible to turn over the propellers without the great danger of injuring some of those struggling in the ocean to keep afloat.

Fortunately, this air attack was unable to penetrate the surface screen, and rescue operations were quickly resumed. When the first rescuing destroyers were loaded, they returned promptly to stations in the screen as ordered, and other destroyers relievcd them in the lifesaving operations. Because of the BENHANI'S position in the middle of the floating mass of humanity in the sea she did not follow the prescribed procedure, but continued rescue operations. We took aboard, in all, 725 survivors of the aircraft carrier, by cargo nets, lifelines, rafts, stretchers and our damaged lifeboat.

The task of caring for such a large number of survivors in so small a ship, with such limited facilities, was a stupendous one. All those taken aboard who were able to walk were directed aft to the fantail, where oil-soaked clothing was removed and thrown in a pile. Several hoses were led out to enable survivors to wash off as much oil as possible. Then the rescued were directed in groups as large as could be accommodated to the boiler and engine rooins, steering engine room and to every available compartment below decks, where they could dry off and warm up. These groups were followed by successive groups until all had been taken care of as well as possible. Officers and men of the BENHAM supplied the naked men with clean and dry clothing from their personal wardrobes. The large number of rescued were crowded into every possible space in the ship for the night. Some forty officers were squeezed into the commodore's small stateroom and day cabin which I used as my in port cabin. They took turns throughout the time they were aboard standing and sitting, and they left behind them oil smudges on the bulkheads. One unusual incident occurred when the crew started to throw overboard the pile of oil-soaked clothing, which had reached such proportions as to seriously impede service to weapons in the fantail area. (BENHAM mounted four five-inch 38's. One five-inch, the depth charge racks; four K-gun throwers and 20 mm. were aft.) A survivor suddenly remembered having left a large sum of money in the pockets of his discarded dungarees. An inspection not only resulted in recovering this money, but much more money and many valuables from the clothing. Money and personal possessions were returned to their owners, who had been much more concerned with the safety of their shipmates than in recovering their valuables.

The final rescue on June 4 by the BENHAM was that of a fighter pilot, a tall Texan, who was spotted on his little raft at sunset by an alert lookout. His shouted comment, as the BENHAM approached him, is worth quoting: "Take your time Captain-I'm in no hurry. This raft won't run out of gas." Subsequently one of his shipmates revealed that this same pilot had been forced down three times recently in flight operations because he had a habit of chasing Japanese aircraft to the limit of his own gasoline supply.

The rescuing destroyers and the cruisers were ordered to retire eastward during the night. Every effort was made by all hands to rendcr first aid to the injured, and to feed and care for the survivors. The more seriously injured were attended in the destroyers wardroom where the ship's doctor, Lieutenant (jg) Seymour Brown (MC), had set up an operating room. Later, when the urgent work of attending the injured was completed, the young doctor learned that among able assistants in the wardroom were the medical and dental officers of the carrier recently rescued from the sea. They had been far too busy caring for those needing attention to identify themselves. Dr. Brown's comment afterwards was: "I thought those volunteer assistants seemed well qualified in rendering first aid."

The task of feeding so many from so small a galley was quite an operation. Soup, coffee, beans and other foods were quickly broken out from the storerooms, and the galley was operating to capacity on an around the clock basis, with the galley force ably augmented by all the cooks among the YORKTOWN survivors.

Shortly after sunrise the following morning June 5, Ensign Pierce was buried at sea. Chaplain Hamilton, recently rescued from the YORKTOWN, conducted the service, and shipmates acted as pallbearers.

The next task on the 5th was the transfer of 7 officers and 16 men, selected damage control personnel from the YORKTOWN survivors, to the ASTORIA for subsequent salvage work. The remainder of the 725 rescued were then transferred to the heavy cruiser PORTLAND, while both ships were underway at sea. Five breeches buoys were used simultaneously to transfer personnel, and the airplane crane of the cruiser was employed to handle stretcher cases, the entire operation lasting nearly four hours. The transfer by means of breeches buovs seemed a comparatively smooth and simple operation from' the destroyer viewpoint. PORTLAND personnel controlled all lines, had more space to work from than the destroyer, and her men were well trained and proficient in this work. Handling stretcher cases was a much slower operation, and required considerable care, since for each transfer the destroyer had to move in very close to the cruiser to enable the airplane crane to reach over to the smaller ship's well deck, and then sheer out as soon as the stretcher was lifted.

About midpoint during this transfer operation, in response to an inquiry from the PORTLAND, the writer estimated total transfers would reach a figure of about 400. The executive officer of the cruiser, Commander T. R. Wirth, then advised that that number had already been received aboard his ship by actual count. When informed then that only about onehalf of the survivors had been transferred his comment was: "You must think this ship is the Grand Hotel."

With the crowded conditions then prevailing in the destroyer, it was difficult to obtain an accurate count, so we were happy to receive the PORTLAND figure as official. Among incidental operations concurrently conducted by the cruiser without interrupting breeches buoy activities were fueling the destroyer and catapulting and recovering scouting aircraft engaged in anti-submarine patrol. The transfer was completed about 1223 June 5. Aboard BENHAM it had been standing room only for almost 1O hours.

Upon completion of the transfer operations the BALCH, BENHAM and HAMMANN were sent back some 150 miles to the YORKTOWN then drifting virtually derelict and severely damagcd, in tow of the ancient tug, VIREO, a converted minesweeper. The destroyer HAMMANN took station alongside the YORKTOWN, put back on board volunteer members of the latter's crew, and also furnished auxiliary power for lighting and operating salvage pumps in the carrier. Salvage work was progressing favorably early on the afternoon of June 6th when torpedoes were reported approaching YORKTOWN from 195 degrees true from outside the screen. A little over two minutes later these struck the HAMMANN and the YORKTOWN at the same time. The destroyer disappeared beneath the sea in about three minutes, and suffered very heavy personnel casualties; the carrier still floated, listing heavily.

It is ironic that the HAMMANN, the only destroyer in the screen equipped to measure underwater sound conditions, had reported earlier in the day that sound conditions were very bad due to thermal layers prevailing in the area at that time, and as a result, destroyer underwater sound detection was reduced to almost zero.

For the second time in three days the officers and men of the BENTIANI were engaged in rescue operations, although this time their task was to prove far more difficult. Many of those awaiting rescue were wounded, a large number severely. The one life boat and life rafts, all badly damaged, had had to be abandoned upon completion of rescue operations two days previously, and there were few medical supplies, or spare clothing left in the ship.

The BENHAM eased into the sea area of struggling survivors and floating debris. Some 18 of BENHAM'S crew jumped into the oily water swimming with life lines to the aid of those in urgent need of help. The rescued were pulled back to the ship, and a great many seriously wounded were lifted aboard in stretchers which had been lowered to the water's edge. First aid for the lightly wounded was administered by members of the crew, for Lt. Brown, the ship's doctor, and his several medical assistants were fully occupied caring for the severely injured.

Too much praise cannot be given to all those officers and men who displayed such selfless devotion to duty in very dangerous Waters in order to save others: swimming to the aid of the severely wounded, resuscitating the apparently drowned, and attending the severely injured, who filled nearly every bunk in the ship until the BENHAM reached Pearl Harbor.

The BENHAM rescued some 200 officers and men on June 6, most of whom were survivors of the destroyer HAMMANN, herself at the time engaged in aiding the crippled carrier YORKTOWN. The other survivors were from the YORKTOWN, a number of these having been rescued from the same ship by the same destroyer for the second time in three days. When I recognized several of the YORKTOWN rescued from their previous "cruise" aboard BENHAM, I could not resist remarking: "The next time you get rescued by a good ship, be sure to stay aboard and don't repeat the ordeal."

The only engineering casualty suffered by the BENHANI occurred early during operations in the debris filled sea, when the starboard main circulator became clogged, and went out of commission. Thereafter there was no backing power on the starboard engine until repairs were effected at Pearl Harbor. Most fortunately full power ahead was available, and that was of vital importance toward completing this rescue mission of delivering wounded to hospitals at Pearl Harbor.

While the wounded were being cared for as well as could be done with the destroyer's limited medical personnel and facilities, funeral services were conducted by the commanding officer for the 26 who died; 16 late on June 6 and the remainder on the next two days. The bodies were sewn in canvas and weighted with drill shells until BENHAM's allowance was gone; then we used live ammunition.

As Captain I conducted most of the services from the forecastle reading extracts from the burial service for the dead at sea from the Episcopal Book of Common Prayer. Lieut. Sloat, the exec, conducted some of the services. BENHAM slowed when the bodies were committed to the deep but did not stop; we were in submarine waters.

At dawn on the 7th the small salvage group still stood by the YORKTOWN in the hope that with additional help reported enroute to the area, it might still be possible to save her. But the carrier settled to starboard, and soon went under as the ships present rendered honors. Aboard BENHAM we stood at attention facing the great dying ship and half-masted our colors.

The BENHAM was directed to transfer all wounded to a submarine tender cruising in a rear area as an emergency hospital, but I reported that many of the wounded were too severely injured to risk transfer at sea at that time. We were then ordered to Pearl Harbor where the best medical attention and adequate hospital facilities were available.

On departure from the area the BENHAM received from Commander Destroyer Squadron Six, Captain E. P. Sauer, a "Well Done," always most welcome by all hands. Fortunately, a calm sea enabled the ship to proceed at 27 knots, and we arrived at Pearl Harbor early in the afternoon of June 9, the first combatant ship returning from the Battle of Midway. At Merry Point the ship was met by Admiral Nimitz, members of his staff, and a large number of medical personnel and ambulances. Approximately 50 stretcher cases, and 25 ambulatory cases were transferred to the Naval Hospital at Pearl Harbor, and U. S. Mobile Hospital Number 2. All other survivors were transferred to the jurisdiction of their respective type commanders based at Pearl Harbor.

The performance of duty of all officers and men during the brief action against enemy planes on June 4, and again during rescue operations on that date and on June 6, was of such high standard as to make it difficult to single out individuals for especial noteworthy performance. But these men and others reflected the highest traditions of the naval service: Lieutenant Frank P. Sloat, Executive Officer, for work at his battle station, and general supervision of all rescue operations, and attention to survivors after rescue.

Lieutenant Robert B. Crowell, Gunnery Officer, for controlling the main battery during air attacks, and maintaining the battery alert for expected additional attacks.

Lieutenant (j. g.) Almer P. Colvin, Chief Engineer, for indefatigable efforts in giving first aid to the injured, and resuscitating the apparently drowned.

Lieutenant (j. g.) Russell Merrill, Communications Officer, as officer-of-the-deck during action and both rescue operations.

Ensigns Oliver D. Compton and James V. Heddell, for assisting injured personnel out of the water, caring for them on deck, and finding places for them in the ship.

Lieutenant (j.g.) Seymour Brown (M.C.) first attended a number of wounded from the action on June 4. For the first two hours after the torpedo attack on June 6, he was the only medical officer attending 82 seriously wounded, and a large number of more lightly wounded patients. Later in the day, Lieutenant (j.g.) Edward A. Lee (M.C.) was borrowed from the BALCH. He remained overnight and rendered most valuable service. Also, Lieutenant (j. g.) J. J. Peterson (M.C. ) was rescued from the HAMMANN, and after recovering from shock was able to help out.

Pharmacist Mate First Class Kenelm Oyches most ably assisted the medical officer day and night from June 4 unil arrival in Pearl Harbor on June 9.

Many others were untiring in helping the medical personnel throughout this trying period among

them:

Pharmacist Mate David Walker, Fireman Jackie Spieler, Mess Attendants Alonza Crawford and

Leroy Spiller.

The point in this story, which is as vivid today to the writer as it was when observed at close hand over twenty years ago, is the extreme danger to which man will expose himself to save his fellow man. There were a great many examples of personal heroism in the rescue operations carried out by BENHAM. Every officer and man did his utmost, seemingly with no thought of the personal danger that was always present from the enemy in the air, and under the sea. This personal heroism may best be described by quotations from two citations (chosen from among many) for awards submitted subsequently:

. . . "On 4 June 1942, in the Battle of Midway, during rescue operations Of YORKTOWN personnel, Coxswain Hughes, Seaman 2nd Class Callon, Fireman Ist Class Sims and Fireman 3rd Class Horton voluntarily manncd the BENHAM'S only available whaleboat, well knowing it to be in dangerous condition with falls cut, engine and hull holed by shell fragments, and that another air attack was imminent, fearlessly launched the boat, and by valiant efforts to keep it afloat and running, succeeded in rescuing a great many YORKTOWN personnel, particularly the more seriously wounded in urgent need of assistance. Their courage and devotion to duty contributed much to the success of the rescue operations and was at all times in keeping with the highest traditions of the Naval Service."

. . . "For distinguishing himself by gallantry and conspicuous devotion to duty while serving in the USS BENHAM (DD-397) in the Battle of Midway on 6 June 1942. With utter disregard for his own personal safety, Chief Boatswain's Mate Webb plunged overboard from the USS BENHAM immediately after the HAMMANN and YORKTOWN were torpedoed, and for more than an hour swam in sea strewn with debris and thick with oil to the aid of seriously injured personnel of those ships. By his great courage, pcrsonal daring and determination, he personally towed at least twenty injured men to safety. His leadership, courage, and devotion to duty contributed largely to the success of the rescue operations, and was in keeping with the highest traditions of the Naval Service."

Editor's Note.

Never before or since as far as Shipmate knows has any destroyer rescued more survivors than did BENHAM during the Battle of Midway. The editor has not combed all the afteraction reports (or ship's logs) of World War 11 but history probably offers no statistically comparable rescue operations, with the possible exception of the British destroyers that rescued the survivors of the PRINCE OF WALEs and REPULSE off Malaya.

The below photos are from the article as published in shipmate and I was unable to improve the quality. however they are legible enough to understand by reading the above account.