Rural Air Service DHC-6 Twin Otter Rural Air Service DHC-6 Twin Otter |

In Search of Brigadoon

(Published in April 1985)

Bario. Perhaps it was the exotic ring of its name, perhaps just wanderlust, which took me to this seldom travelled corner of Sarawak State in Borneo. The morning flight from Kuching was just routine. At Miri, the changes came thick and fast. Rural Air Service flight MH968 sat on the runway. Not the huge jumbo jet one gets so bored with these days but a DHC-6 Twin Otter, a small twin-engined job with a maximum capacity of nineteen passengers.

| The check-in procedure too was surprisingly different - each passenger was weighed, hand baggage and all, to work out the total payload. My excitement suffered an early setback - so intently was I in admiring the aircraft that I

cracked my skull against the low doorsill as I boarded. Nursing a painful forehead, I stooped forward and sat behind the tiny cockpit designed for two. Twenty minutes out of Miri, we came to the first level of hills, a visual relief after the endless monotony of jungle. Five minutes later we were above a winding mountain range that extends over five hundred miles, separating Sarawak from Kalimantan. |

Weighing in at Miri |

To the north lay Mount Murud, over 8000 feet, and Sarawak's highest peak. Extending south and west from Murud, forming a western barrier to Bario, lay the staggered outlines of the Tamabo range. Almost perfectly wedge-shaped, its sides forming steep cliffs that fall nearly 3000 feet to the other side. Beyond the mountain, the land dipped quickly then rose again, as sharply, revealing a series of hillocks scattered like a mouthful of uneven teeth. Then, a view that nearly took my breath away.

A hidden plateau extended before me, about thirty miles across and sloping from west to east. A narrow river wound in and around the foothills down to the plain. On either bank, a sprinkling of houses, metal roofing gleaming in the sun. Around them, a patchwork quilt of cultivated fields with no tall trees in sight for miles!

Bario Airport - Terminal One! Bario Airport - Terminal One! | As the aircraft bumped and bounced along an uneven grass runway and taxied to a halt, my eye ransacked the scenery through the small window, trying to digest the sheer contrasts in the terrain. Twenty yards away lay a wooden shack which served both as a check-in counter as well as the airline agent's godown. |

As I stepped out of the aircraft, another surprise. Before I reached the shed, I was intercepted by an elderly Kelabit lady, her earlobes greatly elongated and decorated by huge brass weights. She came up with a smile, shook hands with me. Then many more smiling Kelabit men and women, with a handshake each, welcomed me to their home country, a typical display of the Kelabit brand of courtesy and friendliness.

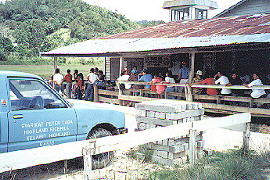

The MAS Agent's office! The MAS Agent's office! | The shack was filled with cargo, just arrived or awaiting shipment. At the far end, on a raised platform, a metal grille partitioned off the Agent's office. To the left, a small co-operative shop and a canteen that served excellent coffee. The two-man flight crew were busy shopping - Bario grows large quantities of a fine small-grained rice that fetches a premium price at Miri. |

Their pineapples, infinitely superior to the lowland varieties, are the sweetest I have ever tasted. It was certainly cheaper eight pineapples weighing seven kilos cost a mere four Ringgit. A stray thought loitered casually through my mind Bario seemed unlikely to offer much by way of accommodation. The MAS Agent directed me to Bario's only hotel, a hundred yards away.

| It was also the only shop in the village. Downstairs a coffee shop, upstairs a spare room which was rented out at eight Ringgit per night. A small clean room, with posters of every imaginable sort decorating its wooden walls - and an enormous double bed. Agreeing to rent the room, I went downstairs. |

The local coffee shop |

The pilot was having coffee with three young men who promptly invited me to join them. Two were local schoolmasters, Ganang Aran being a local and Ghat anak Belabot, an Iban from Kanowit. The third, Peter Matu, also from Bario, invited me to stay at his longhouse, tactfully suggesting that I move in the next day since I had already contracted to hire the room above! The

young Kelabits spoke surprisingly good grammatical English and our talk continued all through the day as they satisfied my curiosity.

The grass runway at Bario The grass runway at Bario | Though quite scenic and picturesque, the unsurfaced grass runway at Bario, built in 1963, makes for extremely dangerous flying conditions. Not too difficult normally, it becomes positively treacherous when wet. No great matter under normal circumstances but critical for the Bario people. You see, there is only one way to reach Bario - by air! And only one flight daily at that. |

This flight is now an important part of their lives, in fact, almost a

social occasion and part of daily routine. Every morning, the Kelabits converge on the airstrip - to catch a flight, to see someone off, to meet someone, or to export their produce. When a flight is delayed or cancelled, the pragmatic Kelabits take it in their stride, calmly go home and return the next day as

though nothing had happened. It was recently estimated that, on average, flights to Bario were cancelled one day in four. Once, the river burst its banks and flooded the area. The airstrip and the agent's office were under two feet of water and Bario was cut off for five whole days.

| What do they do in the event of an emergency? I asked one of the young men. He shrugged off the question with a smile. They make a one-day hike through dense jungle to Ba Kelalan which has a better runway and more regular flights. Unless one is prepared, like the Kelabits, to use the old trading route to Marudi, an arduous hike over the mountains, through thick jungle. "How long does the journey take?" I asked Peter. He hesitated, looked at Ganang, then back at me. |

Jungle trekking in Bario |

It took them three days to walk to Long Lelang, four more from there to Marudi where the Kelabits sold their produce or traded them for other commodities. The route to Lawas took a full ten days. But there was no telling how long foreigners would take for such a jungle trek. He told me a story of a Frenchman who, not very long ago, had attempted that tough trek. Starting off with a huge backpack, he soon opted for survival. The trail he had taken was littered with bits and pieces he had discarded when the going got hard. Towards the end, he had even discarded his camera!

Scenic view of Bario

Scenic view of Bario | Later, during lunch, we were joined by an elderly Penan hunter carrying a blowpipe made from a long block of hardwood. He handed me the darts carefully - about eight inches long, the pointed end tipped with poison, the other end covered by a pad of soft pith. The poison was made by drying the sap of the upa tree. |

The cake of black resin thus obtained is later wet and smeared onto the end of the dart. Two types of poison are used, one of which kills the victim by attacking the nervous system. The old man chuckled as he related this. "Best to hit the pig here," he said, pointing to his chest. "But a hit on the foot is enough. Then light a cigarette and, when it is finished, take the pig home!" Apparently, the pig collapses within three paces of being hit.

The conversation continued until it got dark. Someone lit a spirit lamp which, without a glass cover, spluttered and hissed. Many insects attracted to it got incinerated with a crackle and joined a growing pile of other dead insects beside the glowing mantle.

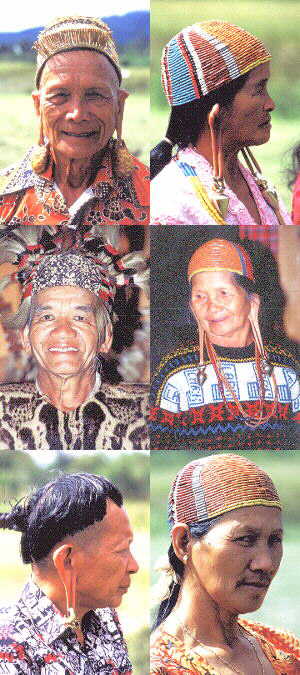

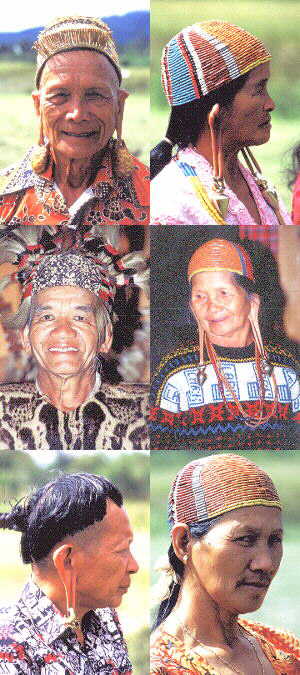

Kelabit men and women Kelabit men and women | I expressed surprise - surely they had electricity? My companions grinned. The power generator, kept inside a locked store room, could not be used that night. The store room key, and the key chain it was on, had gone to Miri to watch a football match, with its owner! Bario is like that, full of surprises and contradictions, the greatest of which is its history. Just fifty years ago, they had been feared, a tribe of fierce warriors, ruthless headhunters too. Their homeland, beyond the reach of most travellers, was given a wide berth by neighbouring tribes. In his book, The World Within, Tom Harrison, a former Curator of Sarawak Museum who first met them during World War II, says the word Bario itself is an amalgam of two Kelabit words, (Ba' meaning wet and Riyo meaning wind) literally means "wet wind". Which sums up the Bario climate to a fine T. Over the next forty years, the tribe was propelled into the 20th Century ways of life, the changes having come thick and fast. |

© Pun Ritai (Updated on 15th April 1998)