Closely related to Sarawakian tribes such as the Kenyah and Kayan, closer still to the Muruts, the Kelabits are distinct in many ways. Like hill people the world over, they have strong legs and thighs. Under broad conical hats, they wear their hair long at the back or done up in a bun held in place by pins of metal or horn. Around the waist hung a long sword-parang with its curved staghorn hilt and wooden scabbard.

Their ears, pierced during infancy, had two holes. The bottom hole, greatly extended by brass weights used as ear rings, often hung down to the shoulders. In the upper hole, kept open by wooden plugs, warriors wore leopard's fangs that pointed outwards beside their eyes.

Kelabit women Kelabit women | Their eyebrows were plucked for the sake of beauty. The women wore elaborate tattoos with a fine lacework of dots and

lines that took several years to get right. Almost the entire lower limb, from the foot to well up the thigh, was so decorated that from a distance, it was as though they were wearing blue-black stockings. They also wore brightly coloured skull caps. |

The changes in their lifestyle are easily dated. Those born before or shortly after the war, have traditional Kelabit looks despite their western clothes. Many of them speak only the Kelabit language - a few speak a little Malay and English, though less fluently than the younger set. The men have pierced earlobes, a custom the young men have forsaken. Nevertheless, many traditions have held firm and Bario is quite unlike other parts of Borneo. Even the countryside is different- the distant hillslopes are jungle clad but not the plateau itself. The coconut trees are recent introductions.

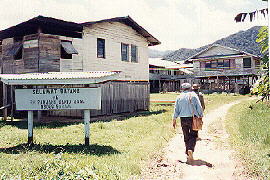

| There are no roads, just a track from the airstrip to the first longhouse at Bario Asal. It then degenerates into an uneven path that vanishes into the foothills. Once, there were four cars in Bario, now only two, the others having long since given up the unequal struggle for survival. Most people walk, a few have bicycles or mopeds. |

The road to Bario Asal |

I rose early the next morning, eager to make a tour of exploration. My first resolution, to take a bath, soon vanished- the water was extremely cold! The valley was invisible, enveloped by a blanket of low clouds. Only a white effulgence marked the whereabouts of the sun. Around seven, the clouds began to retreat up the hill. Barely visible through the mist, two hunters stalked up the mountain trail, one carrying a shotgun, the other a blowpipe. They were after wild boar which, early in the morning, feed in the foothills before moving up into deep shade as the day gets warmer.

It took me three pleasurable hours to cover the two kilometres to Bario Asal. Not so much because I walk slowly, more because I met many villagers en route and the proprieties had to be observed.

The rice harvest The rice harvest | They all found time to stop and smile, to shake hands and have a chat with the stranger in town. The elaborate and courteous ritual greeting begins with the shaking of hands even the ladies and young children do. Then the formalities are met. "Welcome to Bario. Where do you come from?"

"From England", I reply.

"Where are you staying?"

"At the lodging house".

"Will you be staying long?"

"Just a few days." |

The conversation then gracefully moves to other topics. There were no frowns or hostility, no sense that a stranger was to be no more than endured or kept at a distance. Instantly one gets that wonderful at home sort of feeling, of contentment and peace. However, every such encounter left me a sense of dissatisfaction. I could not help but feel that our western culture generates caution, a certain sense of wariness with strangers. Perhaps, my inability to be as spontaneous as the warm-hearted Kelabits made me far the poorer person. I always seemed to be responding to them, never actually initiating the friendly overtures.

Since I was staying in Bario for only a couple of nights, I regretfully declined Peter's offer to stay in his longhouse but joined him for lunch instead.

In most respects, it resembled the longhouses of yore, the building being over a hundred feet long, raised on stilts about seven feet above ground level.

| It had an enclosed verandah running along the entire length of the building. This verandah is the focal point of longhouse life. It is at once a place for family or communal ceremonies, for relaxation and recreation as well as a council chamber for debating communal matters, even a court house! |

The longhouse verandah |

Rather like a small village except that it was under one roof. But it was very modern too, and fitted with ready-made doors and windows, the latter fitted with glass. Peter's room, except for its wooden walls and windows, was just like the room of any young man anywhere in the world. The usual hi-fi set, wall-posters of pop singers and English footballers, and modern furniture.

Lunch was a simple affair, a thick pork stew and a cake of glutinous rice. The Kelabits are great rice eaters, and have three almost identical meals a day, with rice as a staple.

Lunch in the longhouse

Lunch in the longhouse | But that day, normal routines were disrupted an elderly aunt, cleaning beneath the longhouse had been bitten by a king cobra resting inside some bamboo. She was rushed to the small clinic about two kilometres away for treatment. Had her conditioned worsened, the Flying Doctor service would have been called in to treat or evacuate her. |

Fortunately, the fang had only grazed her - after an uncomfortable day or two, she would be back on her feet. The anxiety settled, the family members returned to work in the rice fields.

Between Bario Asal and Arur Dalan, a small brook, about four feet wide, runs between padi fields and cordons of bulrushes and tussock grass. In these clear-running ice-cold waters, and that of countless other small streams like it, lie the origins of the Baram River - at its mouth, nearly half a mile wide.

| Unlike the shifting cultivation methods practised by the lowland tribes of Sarawak, the land in Bario is under permanent cultivation. Not all the fields are cultivated every year. The fallow plots, which never dry up, teem with fish which provides an alternate source of food. The Bario weather was fascinating, being more temperate than tropical. What a delight it was, to go tramping through the foothills, for over ten miles, without once breaking into a sweat despite the bright overhead sun. It was mid-afternoon by the time I reached Arur Dalan - the sky was a brilliant blue with not a cloud in sight. |

Bario pineapple |

By three in the afternoon, a few clouds had formed, to grace the hills surrounding the valley. By five, these were completely shrouded as the clouds rapidly crept down the slopes into the valley itself. Suddenly, it was dark, and the whole valley was filled with white, reminding me of the fog-covered streets of London long ago, but a lot nicer without the pollution of smog.

Bario. Definitely a place worth returning to for a longer stay - and accept Peter's offer that I come back during the school holidays and spend a month or two with him, to jointly undertake that marathon hike down to Marudi. An offer I shall find hard to refuse.