of a Lost World

(By Bulan - Published in 1993)

| of a Lost World (By Bulan - Published in 1993) |

Bario, a swampy highland plain deep in the interior of Sarawak, and barricaded by forested mountains near Kalimantan and Brunei, had defied significant discovery by the outside world till the closing years of World War II when several Australian and English soldiers literally "dropped in" in 1944. These men had parachuted deep behind the Japanese lines in the hope of setting up an Allied base for clandestine military operations.

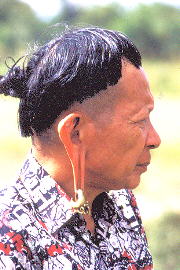

| While floundering about in the boggy ground, they were rescued by a small tribe of highland headhunters few people knew anything about - the Kelabits. This contact catapulted them from their tribal ways into the 20th Century. The Kelabits went on to prove their valour in that war and again during the confrontation with Indonesia in the early 1960s. They have had war heroes and Olympic champions, became Christians and got educated. Today, they have among them entrepreneurs, doctors, lawyers and other professionals working in towns in Sarawak and cities around the world. |

Kelabits may spend years away from their homeland because of their careers, yet they think fondly of going back to the pastoral life of Bario, the heart of the Kelabit Highlands.

| In Bario, their absence is felt by relatives and neighbours in more than a few ways. It has now become necessary to hire Indonesian labourers to help plant and harvest the Bario's prized strain of rice. Thoughts are now turning towards buying harvesting machines to solve the labour problem. |  |

It boggles the mind to realise that there are just over 5,000 Kelabits today, half of whom still live in Bario. The elders in the community grew up in an age guided by pagan beliefs. The youngest ones will grow up guided by the Ten Commandments. For the moment, the past and the future are bound by the present, through occasions when families gather to practice an old Kelabit tradition of changing names with the birth of their first child or grandchild. In spite of their small numbers, one of the most remarkable things about this race is their openness and willingness to embrace change, confidently seeking better lives.

| Yet perhaps the biggest threat of change to their society today is not in the veneer of 20th Century materialism they have begun to acquire, but the potential invasion of 20th Century culture borne by tourists to their home in Bario. "Bario is a beautiful spot with some breath-taking scenery. The forest is fascinating, the butterflies a delight. The views...are spectacular." Jim Heal, teacher, Singapore. This quote, and others given below, are extracts from a guest book at a lodge called Tarawe's in Bario. It lies barely a hundred metres from the grass airstrip where a 19-seater Twin Otter flight lands daily. |

This aerial legacy of WWII is Bario's fragile umbilical to the outside world - and responsible for making Bario the logical tourist hub in Kelabit country. Less than ten years ago, there were no tourist facilities in Bario. In fact, there was no need. Tourists were rare and travelling tribesmen could always count on longhouse hospitality to provide them with food and a place to sleep. This tribal hospitality still exists and is part of the powerful draw for tourists seeking a different kind of a holiday in the wilderness of Sarawak. "The only trouble with walking between Kelabit longhouses is you get given so much food to eat, you can't move! .... Our third time back to Bario and still there are more places we want to visit. It is a lovely area to explore and meet friendly people." Becky Lewis, Teacher, UK. Today, there are three lodges for tourists such as Becky Lewis and Jim Heal. It could be seen as an assertion of pragmatic Kelabit sensibilities.

| Tribal customs consider it an honour to host a guest and an insult to be offered money for it, but when visitors start showing up more frequently and in ever growing groups, longhouse routines are disrupted. Not only does it mean dipping into precious food stores, but other domestic chores and fieldwork could be neglected to keep guests fed and entertained. |  |

The lodges become an acceptable, if opportunistic, way of protecting the community. By the same reckoning, so are the shops. One well-stocked store proclaims itself a Mini-Mart on a rustic signpost, and yes, it stocks mineral water and Coke. The number of tourists triggering changes in Bario is far from large by global standards. Locals estimate it at about 30 to 50 people a month, depending on the season and the availability of flights. Yet it is enough to set new changes in motion, not just among the Kelabits, but also among their other tribal neighbours, the Penans and Muruts. Between them, they account for about ten tribal settlements in the Kelabit Highlands.

| The strain of tourists on the people is acknowledged by one city-dwelling Kelabit. "They worry about providing you with things that you are familiar with - like coffee or tea - which they otherwise won't take." For all the stress tourists bring, the Kelabits and other tribes continue to make time for strangers in the most delightful ways. |  |

"...always a very warm welcome with tea and fruit and good dinner or lunch. Wonderful to see that people are so generous (to) strangers knocking at their door..." Roos Hub and Egbert Bean, Product Manager and Currency Manager, Amsterdam and Netherlands. "...some of the most basic but most civilised people I have met. Us 'city-slickers' have much to learn from the Penan-Kelabit people here." Mike Saxon, Teacher, UK.

| Some tourists, aware of the delicate balance of these rural communities, try to offset the impact of their visits by making it a point to buy some tribal handiwork to make up for what they have accepted of their hosts' generosity. The preferred thing to do, however, is to return the courtesy and hospitality with gifts of food and clothing in lieu of money. |

"...Popular gifts are tea, sugar, tinned meat/fish, sarongs...." Kathleen Seas, Teacher, USA. "...What you give, you will get back threefold in good feelings." Laurie Pierce, Training Consultant, USA. An encounter with this gentle spirit of tribal giving is an intrinsic part of experiencing Bario, even if you don't stay at a longhouse. On jungle trails that connect longhouse settlements around Bario, everyone you meet on foot will stop to at least say hello. Often, questions are exchanged in greeting. In their former world, this was both a courtesy as well as a way to gather news from visitors, to satisfy their curiosity about the world beyond their own.

| However, it is their world of longhouses and jungle trails in some of the most pristine rainforests in Borneo that the outside world is curious about. The beauty of the trails are turning the area into a popular trekking destination. Specialty tour agents have begun to charter Twin Otter flights to bring groups in. |  |

"Enjoy the walking and people. Great pitcher plants in the low heath forest, especially on or by moss beds." Jim Jarvie, Tropical Botanist, UK. "Superb trekking in the forest." Rugby School Borneo Expedition, 1991.

| What the tourist sees as a natural wonderland, the locals see as an essential part of life. The forest is still an important source of food. It is also the only way to get fresh meat in the highlands. Bario is no place to be fussy about your diet. By and large, the current crop of tourists take what is offered in their stride. "Food consumed, apart from the excellent Bario rice, included fern shoots, tapioca and young tapioca leaves, mountain rat, wild boar, sambar deer, mousedeer, range chicken and monkey, courtesy of our various longhouse hosts." Andrew Chan, Private Banker, Singapore. |

"Best food in Borneo here. Best climate too!" Andre van Der Schen, Engineer, Holland. Generally, Bario's highland location means comfortably cool weather. It is a delightful change from the sweltering humidity of the lowland rainforests. While it can be warm enough to need a hat and sunscreen when walking through open country during the day, night temperatures sometimes fall as low as 11 degrees Centigrade. The cool weather certainly encourages walking - thankfully, since walking is the only way to get from place to place. The terrain varies with the weather and local walking times should be taken with a large dose of salt.

| "6 Kelabit hours walking = 9 European hours struggling." Judith Gorst, Nurse, Australia. "Planning to continue to Ba Kelalan, but my body is going to require some convincing..." David Jones, Mechanical Engineer, USA. "...Beware the very bloody leeches." Theo Lecther, Telecom Engineer, Holland. |  |

It will take more than struggling and leeches to keep the intrepid tourist away from a gem like Bario, which recently got a mention in a popular series of guide books. How much longer can Bario maintain its natural and tribal integrity? Here, Bario's natural obstacles are perhaps also its blessing. "A lovely little place. I hope we can get out though..." Nicki Wrighton, NZ. The weather is a wild card to contend with. The grass runway is treacherously slippery when wet, and flights are likely to be cancelled because of it. During a particularly wet season, there were no flights for two months. *(See note below) Anyone bent on leaving can choose to hike through the mountains to the next airport and hope that the weather is better there. That's at Ba Kelalan, a two-day walk away - according to the locals. These obstacles may just give a chance for the Kelabit people to come to terms with the growing interest in their homeland on their own terms. Who knows, perhaps wishes do come true after all... "...I hope the Kelabit Highlands will last and won't be disturbed by too many tourists!" Marielu de Roode, Archaeologist, Holland.

| In Search of Brigadoon | Footloose In Sarawak | Pun Ritai's Home Page |

(Updated on 15th April 1998)