Weirdling 2007 (SC GN) 128 pages

Weirdling 2007 (SC GN) 128 pages

Written and illustrated by Mike Dubisch.

black and white. Letters: Jeff Eckleberry.

Written and illustrated by Mike Dubisch. Weirdling 2007 (SC GN) 128 pages

Weirdling 2007 (SC GN) 128 pages

black and white. Letters: Jeff Eckleberry.

Rating: * * * * (out of 5)

Number of readings: 1

Suggested, mildly, for mature readers

Published by Strange Fear

The Weirdling is a dreamlike blend of horror and science fiction, deliberately owing a lot to H.P. Lovecraft, and with a tip of the hat, perhaps, to William Hope Hodgson. The story jumps between two realities, so you're not entirely sure which is "real" and which a hallucination, but for the sake of a starting point, we'll say it's set in the far future, aboard a spaceship prowling the deep oceans of an alien planet -- humans at war with the bizarre inhabitants of said planet, the Xax, who have the disconcerting ability to pass effortlessly through the ship's hull. Anna Mandretta is a conscripted medic aboard the vessel, where induced dream periods are part of how the ship's crew resist becoming unhinged by their surroundings.

But in Anna's case, her dreams are far from comforting as she finds herself living a parallel life as an early 19th Century physician whose latest case leads her to a demon-worshipping family, perambulating corpses, and a conspiracy to use Anna as the key to summoning an ancient, dark god. When events aboard the ship start echoing aspects of her dreams, she realizes it may be far more than a dream.

Writer/artists Mike Dubisch's graphic novel is one of those things that is supremely effective at times, moody, intriguing, drenched in atmosphere...but also threatens to get away from itself, as the whole what's real/what's not aspect can reach a point where you aren't sure whether the story truly makes sense...or is even supposed to. Well, as it progresses, it seems as though it is supposed to make sense, that it's not just a bunch of weirdness, and that there is some sort of conspiracy orchestrating things.

Visually, it's quite impressive, the black and white art lush and evocative, creating the different environments with ease (sci-fi ship, Edwardian New England). Perhaps most intriguing, I've long thought Lovecraft -- or Lovecraftian at any rate -- stories would be hard to translate to a visual medium, the horror factor of those written stories often based on "unnameable" and oblique concepts where to visualize it literally would be to rob it of its effectiveness. Yet Dubisch manages the intriguing job of somehow managing to depict the horrors of strange creatures like the Xax, where the image is clearly before you...yet where you still can't entirely tell what you're looking at. The creepy, unnameable aspect remains intact.

In story and art the whole thing evokes the palpable mood of some vaguely arty horror film, where the horror is as much based on a simple unsettledness as anything jumping out at you, where things are off-kilter and enigmatic. You can almost think of it as if David Lynch had directed the Matrix movies and injected them with some Lovecraftian Elder Gods mythology.

Yet he keeps you with him for the most part. For all that even by the end I'm not sure if I fully grasped what was supposed to have occurred, and the story itself could perhaps have been tightened (there seem to be a few scenes that kind of reiterate earlier scenes, and I even wonder if the story was originally intended to be serialized in shorter instalments), it holds your interest, and creates its own dreamlike atmosphere where you want to see how it all unfolds.

And to re-read to see if it does hold together, after all.

Listed cover price: $__ CDN./ $15.95 US.

Written and illustrated by Alan Brody. White Shaka Boy, vol. 1 2008 (SC GN) 64 pages

White Shaka Boy, vol. 1 2008 (SC GN) 64 pages

Rating: * * 1/2 (out of 5)

Number of readings: 1

Published by TM Press

Additional notes: music CD included

White Shaka Boy left me kind of mixed in my reaction, both in what I liked and disliked about it, and also in how it fits into my personal review criteria.

Though fiction, it takes its cue from a 19th Century historical incident wherein a white man in Africa was made an honourary Zulu chief. The fiction starts out in modern times when Brad Mahon, a white American teenager -- and aspiring rapper -- is told that his application for a college student loan is turned down because the administration believes him to be the wealthy heir to an African kingdom. Brad goes to South Africa to learn the truth...and quickly finds things are more complicated -- and dangerous -- than he expected. The land in question is at the centre of a (sometimes armed) dispute between various gangs, squatters and more. Even Brad's claim of ownership is up in the air due to complications inherent in South Africa law.

A fact that doesn't stop people from threatening Brad's life, forcing him to go into hiding...while also starting up a popular rap act in South Africa.

The art is fairly simple and minimalist, and though the nature of the script would challenge any artist (as it's a lot of talking heads) writer/artist Alan Brody (whose professional background isn't in comics) relies too much on just drawing the heads; the flow of scenes, even who is in the scenes, is often poorly portrayed. Just in the beginning there's a scene where Brad's sitting at a dinner table and it's unclear: where he is (a home or a restaurant), who the people are he's with (friends? family? roommates? maybe band mates?) and how many people are in the scene (the establishing shot shows two people other than Brad...then there's another character in the next panel).

The writing is likewise uneven, with poorly defined scene changes, awkward dialogue, etc. The history/politics requires an awful lot of explanation, and sometimes it succeeds...and sometimes you still find yourself confused. Toward the end, there's a sudden suggestion a sugar cane company might be involved in all the skulduggery...but we had no hint there even was a sugar cane company! There's also some odd repetition: like Brad being told the same story of a legendary Zulu warrior by two different people in two different scenes!

Heck, even the title seems confused. On the cover it's "White Shaka Boy"...on the spine it's just "White Shaka"

And yet...

There is something genuinely compelling about the material. Brody may have trouble in the execution...but his basic story ideas are pretty good, and the overall pacing is snappy. The very nature of the talking heads and abrupt scene changes -- its paired to the bone storytelling -- means he crams a lot of plot in. Though the material is not inherently juvenile or childish, one suspects Brody sees this as aimed at younger readers, perhaps explaining the art and writing.

You can't help but feel it might make a pretty good youth-aimed movie, with its fish-out-of-water premise, its "Princess Diary" aspect of the poor kid who learns he may inherit a fortune, and the "musical" aspect of him being an aspiring rap musician...albeit with a more adult political edge. Which is both a compliment...but also problematic. 'Cause it ain't a movie! The comics biz these days has seen an influx of companies and creators who seem to see the art form merely as part of a mercenary business model or a cheap stepping stone to some other media development (movies or videogames or trading cards or whatever).

And that's a disservice to the medium...and the readership.

The book is even sold with a CD of "African Township Hits", indicating a cross media marketing campaign was very much at the book's core. And in some press releases Brody is described as "famous for setting off major trends" (whatever that means) and the story has "movie possibilities". The comic appears to be self-published (common in modern comics and not inherently a mark against it) which probably goes some way to explaining the hyperbole (I mean, describing Brody as "famous"...when his bio is pretty Spartan). I even found myself a little skeptical about Brody's claims to how radical and unusual the milieu is...but then I realized I may not be considering the insular American market. Here in Canada there have actually been TV series (admittedly, short lived) set in South Africa, such as Jozi-H, so it's not like my vision of modern Africa is some 19th Century stereotype of loin-cloths and straw huts.

The copy of the CD included in the book I was sent (for review purposes) doesn't actually list the artists involved. It seems an odd thing to do...to say, hey, here's some great music...and then suggest the artists are irrelevant (but maybe this was an advance, unfinished copy). For that matter, in one interview Brody refers to having done the art layouts, but getting another artist to help finish the work...yet nowhere in the book is another artist acknowledged.

And the book carries the hefty price tag of $19.95...for a 64 page comic of barely more than digest-sized dimensions! And a 64 page story...that doesn't end!

This is volume one of a proposed series. To me, a graphic novel (as the work is described in the press releases) should tell a story -- beginning, middle and end. And I've said before that I try to review things from the point of view of saying: if you find this on a shelf, by itself, is it worth picking up? But I realize a lot of people maybe don't see it that way, particularly with the influx of Japanese Manga which are graphic novels in thickness (sometimes a couple of hundred pages) but where individual volumes are nothing more than the latest instalment...just like American monthly, 32 page comics.

Which is why I'm mixed. There are problems in the art and storytelling...but the overall story is sort of interesting. But $19.95 for a 64 page "to be continued" comic and a CD of uncredited South African pop/rap tunes?

Cover price: $__ CDN./ $19.95 USA.

Xenozoic Tales, vol 1: After the End 2003 (SC TPB) 160 pages

Written and Illustrated by Mark Schultz.

Written and Illustrated by Mark Schultz.

Black and white. Letters: unbilled.

reprinting: Xenozoic Tales #1-6, plus a story from Death Rattle #8 - 1986-1988, originally published by Kitchen Sink

Additional notes: intro by paleontologist Philip Currie; sketchbook.

Rating: * * * * 1/2 (out of 5)

Number of readings: 1

Published by Dark Horse Comics

Suggested (mildly) for mature readers (violence)

Xenozoic Tales is set hundreds of years in the future,

after one of those ill-defined apocalypses that arise in science fiction.

The world is now comprised of human tribes, still living much as we do

now -- with local governments, and people dressing in familiar styles --

but in the wreck of the ancient cities, with much of our current technology

lost to them. Oh, and dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures roam the

earth. And that's the gist of the series: people living with dinosaurs.

But not the friendly dinos of, say, "Dinotopia", these are wild beasts,

best avoided for the most part.

The protagonists are Jack "Cadillac" Tenrec, an iconclast

who ruffles the tribal government's feathers even as they often call upon

him to save the day. He acts as a guide, policeman, and all around trouble

shooter when he's not in his garage, retooling classic 20th Century cars.

Jack is also something of a self-styled shaman, very much into an ecological,

balance-of-nature philosophy. His chief foil is Hannah Dundee, an ambassador

from another tribe, very much Jack's equal, and the two bicker so much,

you can't help but assume, in true narrative tradition, that they'll eventually

end up together.

Mark Schultz's well-regarded comic book series has risen

again and again, not unlike the prehistoric creatures that people its pages.

Originally published by the now-defunct Kitchen Sink Press, the original

issues were later published as Cadillacs and Dinosaurs -- in colour

-- by the Epic line of comics (an imprinnt of Marvel

Comics that I think has long since been discontinued); Schultz also licensed it to the short-lived Topps Comics, to produce

a series (also under the title Cadillacs and Dinosaurs) by other

creators. Hmmm. There seems to be a pattern of mass extinction involving

comics companies that publish the series. Dark Horse had better watch out,

because it has recently released two TPBs collecting the complete original

series in black and white (volume two is reviewed below). Along the way, the series also was turned into

a network cartoon -- short-lived.

So why has a series that only produced a little over a

dozen issues more than fifteen years ago enjoyed such periodic resurrections?

'Cause it's a lot of fun.

It's clear pretty early in this first of the two volumes that Schultz has a creative vision

firmly in his mind. Xenozoic Tales is an unapologetic mix of old and new,

of nostalgia and New Age. It's set centuries in the future, but characters

dress in safari suits like out of a Jungle Jim comic strip and cruise around

in classic 1950s cars. And what exactly is the scientific rationale behind

dinosaurs walking the earth? If questions like that bother you, move on.

But Schultz isn't just writing and drawing an adventure series...he's writing

and drawing an adventure series that seems like the sort of thing we all

would've read growing up, but never did. Schultz's art style even borrows

from classic past masters like Wally Wood and a bit from Al

Williamson (not to mention later talents like Berni Wrightson with his

feathery inking). With the evocative illustrative style, Xenozoic Tales kind of seems like it might've been an

old EC Comic. Rough n' ready, gruff Jack Tenrec is a pure 1950s hero, and

ballsy Hannah is just the kind of foil you'd expect for him.

There's a hint of cartoony exaggeration early on (burly

guys' shoulders seem a bit too broad, jaws a little too jutting) but that

becomes less as Schultz refines his style. Throughout, Schultz, who was

fairly new to comics at the time, shows a surprising eye for just telling

the story with his images. The pictures can be striking, moody, artfully

rendered, but above all, they serve the narrative, not the other way around.

Perhaps also reflecting an EC influence, some of the stories are unnecessarily

gory -- unnecessary in a series that is otherwise fairly family friendly,

with little cussing or sexuality. Though, even then, the violence often

feels more explicit than it really is -- a lot of black ink blood when

a dinosaur attacks. And Schultz seems to move away from the violence as

the stories progress, with the most, uh, gooiest story being the very

first published (in a horror anthology called Death Rattle) though it's

inserted in the middle of this collection.

Just as an aside, Schultz -- as a writer -- would

later team up with venerable Al Williamson to produced an entertaining, two-issue Flash Gordon mini-series

for Marvel Comics.

There is an unpretentious simplicity at times, which Schultz

freely owns up to by the fact that some of the stories are only eight or

ten pages long. Instead of stretching something out beyond its interest,

he knows when to close the curtain on a particular idea. As such, Xenozoic Tales can subtly weave a panorama of this fanciful reality, with stories

veering from man-against-man, to man-against-nature, to others that are

more like dramas. When assembled together, these 12 stories

benefit from each other. No one story is, perhaps, a stand out, but none

are bad either. With no story expected to sink or swim on its own,

the book becomes a fun read as you cruise from one enjoyable tale to another.

And just as you begin to become seduced by the intentionally

old fashioned feel, the simplicity to some of the plots, you realize that

there's a subtle sophistication lurking under the surface that probably

wouldn't have been there in a real 1950s series. Though not given to brooding

introspection, both Jack and Hannah begin to emerge as vividly realized,

even believable, people, with foibles as well as virtues (albeit supporting

characters are not as well defined). And the plots can evince a nice craftsmanship;

the stories may not be especially complicated, but Schultz lets them unfold

in a way that keeps you turning from page to page. There are also hints

of an overall story arc, involving learning about the disaster which occurred centuries

before, and a mysterious race of humanoid dinosaurs. But whether such threads

ever paid off, I guess I'll have to read the next volume to see.

Perhaps most surprising is the series' increasingly explicit

enviromentalism that lets you know that, beyond the "gee whiz" adventure,

Schultz is trying to say something.

What sticks with you most about Xenozoic Tales is

simply the milieu itself. Beautifully rendered by Schultz, even in black

and white, the jungles are lush, the city craggy and gothic, the dinosaurs

carefully rendered; the men are rugged, the women pretty. Perhaps reflecting

its nostalgic roots, even when Schultz indulges in a little salacious cheesecake -- such

as a sequence where Jack and Hannah go fishing, and Schultz presents Hannah

in a few blatantly fetching poses -- she's still dressed rather demurely

in a one-piece bathing suit. Oh, well, he can't get everything right!

Fantasy fiction is very much about escapism...and who

of us hasn't fantasized about a world of prehistoric dinosaurs, where the

concerns of our everyday lives are no longer relevant? Welcome to the Xenozoic

era...you just might want to stay awhile.

Cover price: $__ CDN./ $14.95 USA

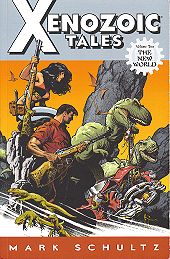

Xenozoic Tales, vol. 2: The New World 2003 (SC TPB) 176 pages

Written and illustrated by Mark Schultz.

Written and illustrated by Mark Schultz.

Black & White. Letters: unbilled

Reprinting: Xenozoic #7-14 (1988-1996)

Rating: * * * 1/2 (out of 5)

Number of readings: 1

Additional notes: intro by Frank Cho; afterward by Mark Schultz; sketch gallery.

Mildly suggested for mature readers.

Published by Dark Horse Comics

This is the second of two volumes (the first is reviewed above) published by Dark Horse comics collecting, in its original black and white, Mark Schultz's well-regarded, off-beat adventure series Xenozoic (also known as Cadillacs and Dinosaurs). Set hundreds of years in the future, after vague cataclysms have destroyed civilization, it follows the adventures of human "tribes" -- mixing aspects of pre-industrial and industrial societies -- in a jungle world repopulated by dinosaurs. It was originally published by Kitchen Sink Press and has been reprinted by other companies -- the latest being Dark Horse.

The stories in this collection are more accomplished, more ambitious, than those in the first volume, and Schultz's art even more breathtaking and impressive -- yet the overall result, though good, is perhaps more disappointing. For one thing, Schultz has dropped the flexible story length of the early issues -- where a story might run anywhere from 8 to 28 pages, which permitted a lot of variety in the types of tales he told, chronicling the exploits of Jack Tenrec and Hannah Dundee and their colleagues. This time out, he's settled on conventional 22 pages per story. And while the early stories could be deliberately episodic, occasionally focusing on a peripheral character rather than Jack or Hannah, delineating this strange new world, here Schultz is more focused on unfolding a story arc. It's not so much that each issue is "to be continued" in a cliff hanger way, but each issue leads to the next, as Jack's iconoclastic nature finds him increasingly ostracized from his own government, eventually having to flee the City in the Sea with Hannah to her tribe, where he gets caught up in other machinations.

Also problematic is that the saga is left unfinished. Oh, there are no cliff hangers, no final issue revelations that leave you dangling. But throughout these issues Schultz weaves hints of a bigger story, or grander themes, and even on the surface there is the saga of Jack and Hannah fleeing Jack's home, then plotting to retake the city from those who exiled him. But the series ends before that can happen.

Schultz, in his afterward, insists he will finish it...someday. And maybe he will. But excuse my scepticism. After all, it's been a number of years, and Schultz has yet to produce any further issues (and he even briefly licensed the property out to other creators under the Cadillacs and Dinosaurs name). And the story threads themselves seem sufficiently amorphous that I could well imagine the reason Schultz has been blocked...is because he's not sure how to tie it all together.

With all that being said, this second collection is still entertaining. Schultz's beautifully shadowed, lush and lavish artwork is, at times, stunning to look at, and has come a long way from the earliest issues (though they were still nicely drawn themselves). And the premise remains irresistible. There's a lot of ambition -- both character-wise and philosophical -- at work in the series, deceptively so, that can be quite impressive. Though, as such, there's a little less emphasis on just the good ol' "Boys Own" adventure aspects that were more pronounced earlier. Though there's still adventure, running about, human villains and fearsome dinosaurs -- there's not as much of that as you might want.

Schultz's handling of the Jack/Hannah relationship is a bit bumpy. I liked the subtle way Schultz was developing the relationship in the early issues, slowly developing a romantic undercurrent without drawing attention to it. This continues that approach, where it's almost a romance, without either character acknowledging it. Except, then, Schultz suddenly accelerates the relationship with the characters falling into bed with each other...when I still thought they were at that "sexual tension" phase. Stranger still, the next issue, they seem right back to being more friends than lovers, as if the physical tryst was a hasty plot point rather than a natural development!

The New Age is an entertaining read and, in many respects, is a more accomplished collection (particularly art-wise) than the first. But the first remains the more entertaining, and remains probably the volume to start with.

Cover price: $__ CDN./ $14.95 USA