Written

and illustrated by Howard Chaykin.

Written

and illustrated by Howard Chaykin.

Colours: Lynne Varley. Letters: Ken Bruzenak. Editor: Mike Gold.

American Flagg: Hard Times 1986 (SC & HC TPB) 90 pages

Written

and illustrated by Howard Chaykin.

Written

and illustrated by Howard Chaykin.

Colours: Lynne Varley. Letters: Ken Bruzenak. Editor: Mike Gold.

Reprints: American Flagg #1-3 (1983)

Mature Readers

Additional notes: introduction by fantasy writer Michael Moorcock

Rating: * * * * (out of 5)

Number of readings: 2

Published by First Comics

Collecting the first story arc from Howard Chaykin's critically

acclaimed satirical science fiction/suspense series, this was set, when

it was first published, decades in the future. Reuben Flagg, one time porn

actor, idealist and Martian colonial expatriate has just joined the Chicago

branch of the Plexus Rangers -- the 21st Century police. America has fallen

apart with the political and business leaders relocated to space: the centre

of Chicago is one giant mall, clean and decadent, while the suburbs are

a no man's land of warring street gangs. Hard Times introduces an

assortment of eccentric characters (including a talking cat named Raul)

while Flagg faces shoot outs, corruption, subliminal messages, beautiful

ladies, and a murder mystery.

American Flagg: Hard Times is refreshingly off-beat,

inspired less by comics or movies (as you might expect) than by -- gasp!

-- literature. Particularly science ficttion novels from the '60s and early

'70s (Alfred Bester comes to mind). In many respects it genuinely comes

across as an adult comic (adult in a good way, not a sophomoric Heavy

Metal way) with edgy, effective -- and witty -- dialogue and convoluted

plotting and character interaction. The character's are well-realized,

even the cat, Raul, who could've been cloying but isn't. The obvious concept

would've been to make Raul eccentric (smoking a cigar and talking in slang

maybe). By making him level-headed, Raul becomes almost believable...which

makes him even more eccentric.

Flagg is also Jewish. It seems odd to comment on that

but, even now, at the dawn of a new millennium, it's curiously rare. Jewish

actors portray heroic, action characters all the time...but how often are

they allowed to portray Jewish action characters? And how many superheroes

are Jewish? Think about it, kids.

Art-wise, Chaykin employs a near flawless, realist style

that is superbly effective and designs elaborate costume and set designs.

Even how the characters dress reflect an artist thinking about every little

button and zipper.

Most striking, American Flagg seems to be the product

of a guy who'd spent many years in comics and wanted to try every trick

he'd ever imagined. Chaykin doesn't just use comics to tell his story,

he embraces them. From eclectic panel arrangements and overlaps,

to even the placing of word balloons and sound effects, American Flagg

tries to see just what the medium is capable of...and succeeds more often

than not. I'm not sure I've seen anyone else, even Chaykin, do as much

with the medium before or since. At one point Flagg prepares dinner...and

the actual recipe is provided in the letter's page! The down side is that

sometimes Chaykin's experimentations don't work as well as he'd like, and

some sequences can be slightly confusing.

There are a lot of wild ideas at work, and the mall setting

creates its own unique ambience. But that's also the problem. Chaykin throws

in a lot of concepts that he only plays with half-heartedly. Hard Times

isn't intended as a stand alone work, but more like a TV pilot -- the main

plot ideas resolve, true, but others are there establishing the premise,

or setting things up (one assumes) for later stories.

The concept here is that America has largely fallen apart

and, as the tag line on the original cover of the first issue says, "someone's

gotta put it all back together". Chaykin conjures up a leftist attitude

-- at one point Flagg denounces capitaliists and is disgusted by the idea

of expensive "nostalgic" jewelry utilizing communist motifs (Chaykin being

one of the few SF writers to anticipate the fall of the Soviet Union, though

for different reasons than really happened) -- but the specifics of his

satirical barbs are vaguer. The Plex, the corporation that runs the U.S.,

has out-lawed sports...but Chaykin fails to suggest why (at least in this

story) unless it's just to provide a politically neutral rallying point

for his readers. Part of the plot involves Flagg discovering a TV show

that induces violence. Aside from the fact that in this storyline we never

really learn why the Plex would do this, is Chaykin really suggesting media

can influence behaviour? Chaykin, who himself has been criticized for the

sex and violence in some of his stories? I'm not saying an artist can't

or shouldn't be incensed or concerned by media violence...I just find it

hard to believe Chaykin is that sincere about it himself.

In that sense, some of the "adult" aspects of the story

seem less impressive. Some of the ideas and satires are, well, obvious

and not sufficiently justified. And Chaykin's portrayal of male-female

relationships shows all the sniggering maturity of a James Bond movie.

Not that I'm objecting, per se. After all, despite the serious undercurrents,

Hard Times is supposed to be a fun romp. And a naughty one at that. This

is definitely a mature readers story. There's mild cussing and grown up

themes and Chaykin depicts the most explicit sex scenes I've ever seen

in a (mainstream) comic. There's no nudity (cover notwithstanding), but

it's still very raunchy in spots.

American Flagg: Hard Times is a fun, bracing read

for grown ups. It's arguably more clever than it is smart, but still enjoyable.

This is a review of the story as it was serialized

in American Flagg comics.

Cover price:

Anibal Cinq: The Last 10 Women I've Known 1997 (HC GN), 62 pgs.

Written by Alejandro Jodorowsky. Illustrated by George

Bess.

Colours/letters/editor:

uncredited.

Colours/letters/editor:

uncredited.

Originally published as "Humano sa, Geneve/Les Humanoides Associes"

Rating: * 1/2 (out of 5)

Number of readings: 1

Published by Heavy Metal

Definitely Recommended for "Mature Readers".

Anibal Cinq: The Last Ten Women I've Known is a raunchy,

SF, spy-parody about a kind of cyborg agent, Anibal 5, working for a futuristic

European spy organization, and his battles with a diminutive megalomaniac,

the Mandarin.

The problem is it's one of those things which refuses

to take itself seriously enough for the reader to actually care about what

happens...without actually being funny enough to qualify as a comedy. It's

bizarre and weird, but to the point where it stops being edgy and unpredictable,

and instead is just plain nonsensical -- eventually inducing a kind of

"ho hum" indifference. Not unlike all those spy parody's Hollywood produced

in the '60s (the Matt Helm movies, the Flynn movies, Modesty Blaise, Casino

Royale).

Even the title doesn't seem to make any sense.

There's plenty of nudity -- some quite explicit -- and

that's its main appeal. But even the eroticism is problematic. One almost

wonders if Anibal Cinq: The Last 10 Women I've Known is intended as much

as a parody of eroticism as of James Bond, because it's often more uncomfortable

and off-putting than exciting: a Lolita-esque character; a gorilla turned

into a beautiful, furry, woman; the one sex scene ending in an assassination.

Even a horde of voluptuous, nude lady storm troopers...who get knocked

around, shot up, etc. One comes away fearing you've gleaned more about

Jodorowsky and George Bess's fetishes than perhaps you would want to.

The art by George Bess is good, but Jordorowsky's dialogue,

like a lot of translated comics I've read, makes me wonder if there were

some mistakes in the translation here and there, because the dialogue doesn't

always seem...right.

Hardcover price: $__ CDN./$14.95 USA

A cheaper version might be to track down a back

issue copy of Heavy Metal Pin-Up (1994) vol. 8, no. 1, the original (U.S.)

magazine version of the story (where I read it). Sometimes Heavy Metal

censors its more risqué stories when publishing them in the comic

magazine, but I don't think that happened here.

Arrowsmith: So Smart in Their Fine Iniforms

see my review here

Artesia

For my review of the Artesia series (including Artesia, Artesia Afield and Artesia Afire) at www.ugo.com, go here.

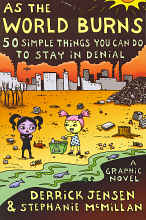

As the World Burns: 50 Things You Can Do to Stay in Denial

2007 (SC GN) 220 pages

As the World Burns: 50 Things You Can Do to Stay in Denial

2007 (SC GN) 220 pages

Written by Derrick Jensen. Illustrated by Stephanie McMillan.

Rating: * 1/2 (out of 5)

Number of readings: 1

Published by Seven Stories Press

As the World Burns is a mix of political polemic and satire, an angry look at the state of the global environment, a bitter attack on politicians and corporations who have brought us to this point...as well as a snide swipe at "liberals" and week-end environmentalists who, in the minds of the book's creators, are living in denial. Basically, the targets are pretty wide ranging.

The ideological heart of the book is that convenient little tips about using fluorescent light bulbs and flushing toilets less often aren't going to do enough to save the planet. Radical, violent action is required.

Unfortunately, as a comic book, it doesn't really work. It's written by Derrick Jensen (a non-fiction author whose bio blurb describes him as an "activist and philosopher") and drawn by Stephanie McMillan, a political comic strip artist, but neither seem entirely adept at dealing with a long form narrative. Characters come and go, talking heads pop in and out, the plot -- such as it is -- lurches about like a drunken blind man. There are pages made up of a single panel crammed with reams of dialogue balloons (as Jensen's background isn't in comics, it's understandable he might have pacing problems).

Some might argue that to judge a political manifesto cum satire by its narrative development is like complaining a still painting doesn't have character growth. But the cover bills it as a "graphic novel" -- and so invites being judged as such. And, in a sense, that's one of its problems. If it was just meant to convey a message and information...the whole thing could've been done as a much, much shorter work.

McMillan's art is of a crude, underground comix style. That's her style, and can suit the tone of the material...but, admittedly, at 220 pages, it means visually the book lacks a certain panache -- in short, it's kind of ugly. While Jensen's story does have a vague plot, involving alien robots making a deal with corrupt politicians to loot the earth; and there are protagonists, two girls, as well as a one-eyed bunny who becomes an eco-terrorist. But it doesn't fully gel into an actual story, per se. There are occasions where we see a glimmer of that, such as when the bunny raids a bio-lab and we discover something about his motivation. But scenes like that are rare.

Admittedly, that's because it's also satire -- but an environmentalist Dr. Strangelove it ain't. There are some funny bits, some genuinely amusing quips, some humorous barbs...but most of it's all pretty blunt and obvious, not exactly rife with wry subtlety. And it's repetitious -- extremely so. The book's just too long. A satirical barb that's funny the first time gets pretty tired the fourth time. At the risk of repeating myself, the book's very length works against its effectiveness.

Which then brings us to the political/ideological core -- what the jokes and the narrative are meant to sugar coat so we can ingest it easier. And that is even tricker to review -- after all, do I review the thesis? Or simply how well the thesis is articulated?

Don't know -- so I'll just press on.

The problem is that the argument put forward is both right...and wrong; both brutally unflinching...and specious and dishonest.

As mentioned, their targets aren't simply the usual suspects, but even the "green" movement itself, suggesting it's been co-opted. The comic begins with one girl excitedly telling another girl how she'd seen a movie (presumably An Inconvenient Truth, but not identified as such) that made suggestions for how to curb climate change, including fluorescent bulbs, using less gasoline, etc. Her Goth friend sighs and explains that things have gone too far for anything but radical solutions.

And here's where things break down.

That character dismisses the "small steps" solution, in part, because it would require everyone to make cuts in their consumption, and that "will never happen". So the proscribed alternative is nothing less than the dismantling of modern civilization, right down to removing "every inch of suffocating pavement" from the earth. Um...the authors feel it's impossible to get everyone to use fluorescent bulbs...but feel that somehow dismantling civilization is more doable? And it ignores the fact that dismantling the current system is rife with its own problems. Consider the concerns about toxins raised after the World Trade Centre was destroyed -- now multiply that by millions of office buildings.

Going back to nature requires a bit of cleaning up, first. The authors mock the notion that science -- which has facilitated the crisis -- will save us. But, to some extent, maybe we have to hope it can (even though I realize that's a bit like an abused wife expecting her husband to help her get a divorce) because there's no easy "off" switch to shut things down cleanly.

The authors simplify the conflict by laying it at the feet of politicians and corporations...ignoring the fact that the "enemy" are also working stiffs who are desperate to stay employed (hence why in recent years, the traditional left-wing alliance between unions and environmentalists has become fractious).

Jensen and McMillan are outraged about so many things, occasionally going onto tangents that have little to do with ecological concerns. What does torture have to do with fresh water? What does the vivisection of individual animals have to do with the greater bio-sphere? Animal testing/experimentation may well be unconscionable...but it's only thematically connected to the larger issue. Unfortunately, the environment requires, sometimes, prioritizing it over individuals.

To go back to a simpler, less technocratic society would, in all probability, require going back to a smaller population (consider that most large mammals -- ie: people sized -- usually maintain population bases of considerably less than even a million). So...in order for Jensen and McMillan's vision to become real...people have to die; most of them, in fact (which then raises further environmental concerns about dealing with rotting corpses). Did the authors not think this far ahead? Or do they just not want to admit it to their readers? There's one point where, listing things we must divest ourselves of, they subtlely slip in "medicine". Medicines are toxins; the leech into the environment and cause further damage. But without medicine, people die. Indeed...why are we trying to cure cancer? AIDS? Why are we sending mosquito nets to Africa to try and curb malaria deaths? The more people allowed to live, the more of a strain on the bio-sphere.

Harsh? Yes. Inhumane? Maybe. And (hopefully) I'm wrong -- but I just don't see how the template of a pre-industrial world can work for six billion eating and pooping people. So why do the authors tip toe around it? Either 'cause they're being dishonest...or they, themselves, are living in denial. For all they're supposedly trying to kick us out of our touchy-feely Al Gore-fostered illusions...the comic involves alien robots and anthropomorphized talking animals. I'm all for metaphor...but surely the authors' point is that the time for metaphor is past, it's time to face reality.

And that's just not something they seem ready to do.

Perhaps they would've better presented their case by doing the story more as realist science fiction -- decide for themselves how changes can, and must, be made, then write a speculative story where that happens; giving us both a narrative, and a blueprint for social change.

As it is, the book is full of philosophical/ideological inconsistencies. The authors denounce the futility of emphasizing individual actions since most pollution is caused by corporations. Fair enough. But it also smacks a little of putting the blame on the "other" ("They're the real problem, not us," as the goth girl insists) and echoing the way the Bush administration (and other conservatives) have rejected the Kyoto climate control accord because some nations are exempt. If more people take responsibility for their individual actions -- something they have control over -- it might lead to a kind of philosophical shift and make it easier to then accept the kind of broader changes the authors rightly feel is needed. (As an example, in Canada, slavery was dismantled incrementally over a number of years -- a kind of weak kneed, go slow approach compared to the U.S. fighting-a-heroically-decisive-war over the matter: yet Canada actually abolished slavery entirely decades before the U.S. and, a century later, wasn't still dismantling segregation the way the U.S. was. Sometimes baby step solutions can be more effective than more dramatic, violent changes).

Besides, corporations are driven by profits which rise and fall on the tides of consumerism...so if people change their individual habits, it might have more impact on the actions of corporations than bombing the occasional factory or dam ('cause history has shown us that terrorism is soooo efficacious in bringing about change, which is why there's peace in the middle east today -- oh, wait, there isn't!) In fact, the authors' advocacy for violent, militant action is also ironic in that, when raging against the cruelty and injustice in the world, they denounce war...yet their climax involves machine gun totting revolutionaries.

Ultimately we have a comic book insisting we must all take direct action, angrily denouncing hypocritical, week-end environmentalists...yet is printed on paper (made from dead trees) and embraced by self-style urban revolutionaries who praise it in their blogs...on the internet...using their computers (with toxic components) that suck more energy from the power system. As the World Burns has some valid things to say -- but as a narrative/entertainment it's weak, and as non-fiction, it side steps many issues in its call to arms.

The bottom line is, despite the good things about it -- the voicing of harsh, maybe uncomfortable opinions -- it doesn't justify its 220 pages. Frankly, it's a slog to wade through because of its repetitiousness. The authors could've said all they needed to say in a fraction of that...and maybe left a few more trees standing in the process.

Cover price: $__ CDN./ $14.95 USA

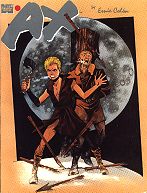

Ax

1988 (SC GN) 48 pages

Ax

1988 (SC GN) 48 pages

Written, Illustrated, painted and lettered by Ernie Colon.

Editor: Sid Jacobson.

Rating: * * * (out of 5)

Number of readings: 1

Published by Marvel Comics

An odd blend of science fiction, fantasy and the surreal,

Ax is about a young boy on a medieval-type planet who, unbeknownst to himself,

is regarded as a prophesied saviour by another, technologically advanced

planet. The technologically advanced people are in a war of their own instigation

with the Aboriginal-type inhabitants of another world -- a war that, despite

their nuclear weapons, they aren't entirely winning against their magically

inclined opponents.

Ax is a not uninteresting story, boasting weird ideas

and such. But despite its length, it comes across like a short story, like

you might read in an old anthology comic like Epic Illustrated or Heavy

Metal or something (well, minus the R-rated material usually associated

with Heavy Metal) rather than a fully fleshed out story. The underlining

logic principals aren't entirely clear, with the story more head trippy

and symbolic at times rather than always presenting a rational cause and

effect. And the characters seem more there to serve the needs of the story,

than as personalities that exist to be explored by the writer and for the

reader to become involved with.

I've often had mixed feelings toward Ernie Colon's art,

a bit cartoony in spots, but here I rather liked it. It suits the tone

of the piece well, telling the tale with energy.

Ultimately, Ax is interesting enough to keep you turning

the pages and boasts some clever turns, but, as noted, it's more a short

story than a full length saga, and is somewhat unsatisfying for that. It's

definitely of the kind of read that says the cheaper you can find it, the

better you'll like it.

Original cover price: $7.95 CDN./ $5.95 USA.

Written by Donne Avenell. Story and art and colour by Enrique Romero.  Axa - Color Album

1985 (SC GN) 48 pages

Axa - Color Album

1985 (SC GN) 48 pages

Rating: * * * (out of 5)

Number of readings: 2

Published by Ken Pierce Books.

Recommended for Mature Readers

Axa was a British newspaper comic strip that ran in the 1970s and early 1980s, a sci-fi series about a beautiful, independent, sword wielding heroine who wandered a post apocalyptic earth, encountering monsters and mutants, and remnants of the old civilizations. It was different from American newspaper comic strips in that it belonged to a long tradition of British strips which -- the British apparently having looser, less prudish standards -- included adult subject matter...mainly nudity, as Axa would not infrequently lose her clothes in the heat of battle, sometimes replacing it quickly...sometimes parading through the rest of the story arc in variuous stages of undress.

The entirety of the British series was collected in a series of volumes from Ken Pierce Books, and Axa even landed a couple of issues of a colour comic from American Eclipse Comics. In addition there was this 48 page graphic novel, titled simply: Axa Color Album (or Adult Fantasy Color Album). The gimmick here was the normally black and white Axa would get the full colour, almost painted treatment, and the rigid, small panel format of the daily strip could make way for bigger panels and less restrictive panel arrangements. And free of the nominal restraints of the newspaper, the material may be even more "adult" in spots (more on that in a moment).

I'm not sure what the publishing history of this was -- it was published in 1985, but the credits list a Spanish copywrite as 1983, 1984, implying this might be the English translation of a Spanish story (though Axa was a British comic strip, scripted by Englishman Donne Avenell, it was drawn by Spanish artist Enrique Romero) and moreso than the black & white strips, there are spots where the dialogue does sound a bit like clumsily translated sentences. As well, the "Axa" logo appears periodically throughout the story, as if these were originally serialized chapters.

The story is, in some respects, meant to stand alone, removed from any obvious continuity (throughout the newspaper strip, Axa usually had a changing parade of sidekicks/lovers, and each story arc followed directly from the previous one -- yet here she is all alone) as if intended to be accessible for a new reader...yet, conversely, it's a long ways into it before we are told a bit of Axa's background, meaning the story might seem a bit untethered for readers wondering "who is this woman and where did she come from?"

The story is a episodic and simplistic -- ironically, it's probably less complex and developed than some of the newspaper strip storylines. Axa battles a monster, gets captured by mutants, escapes, then is beset by wild dogs at a deserted seaside town...losing her clothes with astonishing regularity. Eventually she hooks up with a man and his adult daughter, who have taken refuge in a light house to escape the dogs.

This ain't sophisticated story telling or high art -- there can be a clunkiness to the dialogue and an abruptness to the scenes. But there is an effectiveness to it at times. There is a mood to the richly rendered apocalyptic landscapes, and the very minimalism of the characters and character interaction creates a palpable sense of forlorness -- the characters finding both sanctuary and a prison in the besieged light house. In some respects, this is more melancholy and fatalistic in tone than the daily strip.

Romero is a good artist (the poor cover image notwithstanding), both in his moody backgrounds, and in depicting his people -- for the most part. But he is a bit stiff and seems to reference some of his images -- not only will the same poses crop up again and again, but there's an image of Axa on page eight, panel one that seems lifted directly from an old Boris Vallejo painting (done for the Edgar Rice Burroughs novel, I Am a Barbarian). Still, Romero's art is definitely seem as a big appeal of the series...particularly his depiction of the pouty lipped, under clad heroine.

This is an adventure series...but obviously it also crosses over into being erotica (though falls short of being porn), and there can certainly be a camp value to the way Axa is constantly popping out of her top, or being undressed. If you're prudish, or just fund such titilation too distractingly self-conscious, this isn't for you.

As mentioned earlier, this seems to be going for a slightly harder "R" attitude than the newspaper strip. The violence is a little bloodier, and though Axa was certainly lusted after in the daily strip, it's more explicit here with a couple of attempted rape scenes -- and even an off panel rape (not of Axa). Axa is even depicted in full frontal nudity, something which the daily tended to avoid (displaying her breasts and backside only). Though, curiously, such full frontal nudity is actually rare (in only a half dozen panels in a 48 page story!) -- one might think, if you're going to do it, why be restrained?

I have mixed feelings about this graphic novel -- it certainly isn't a literary masterpiece. But there is a moodiness to it...and an unapologetic sexiness. If you've got a thing for beautiful, wardrobe challenged babes in post-apocalyptic settings, this certainly fits the bill.

Original cover price: $7.95 USA