She swung into the opening licks, tossing off polyphony without thinking.

Out of the corner of her eye, she saw Lisa shake her fist at Melinda and throw

her sticks on the floor. The drummer stalked away. Melinda vanished into the shadows.

Alone on stage, Christa forced herself to nod at the audience. Smiles were beyond her.

She struck and bent a high note, held it as she went to a microphone.

"A friend of mine lost a brother tonight," she said. "This is for Danny."

And she was off again, working her way through an intricate set of variations on the

lament she had once played for Randy Rhoads. Her fingers blurred into rapid scales and ornaments,

froze in place as she let the guitar cry out with grief. For Danny.

Kevin needed help too, however. And so did Melinda. And Monica. And, for that matter,

Christa herself. As she wrenched her music out of the guitar, therefore, she began to add other

themes, other scales and tonalities. The Equinox had arrived, bringing with it the promise of

Spring, and she turned to it and its message, embraced it, celebrated its mystery with music from

an electric guitar and a Laney stack driven to peak. Shouting out the mystery of the new season,

she cast it throughout the club, and its benison enfolded her listeners like broad wings of solace.

The most important inaccuracies in the novel are related to music. Ancient Irish music was almost certainly not polyphonic; polyphony did not become a popular musical style in the West until the heyday of the Gregorian Mass in the Middle Ages. Likewise, the fourteen modes were an innovation of the Church based on the musical research of Greeks such as Pythagoras. Ancient Irish music, and Celtic music in general, relied mostly on pentatonic (five-note) scales, rather than the diatonic (seven-note) modes. Chairiste's cruit, or harp, would hardly be recognizable as such to modern eyes - the triangular frame harp was, according to the evidence of standing stone carvings, first introduced in Scotland by the Picts in about the eighth century, and didn't appear on Irish stones until the ninth. The cruit was probably more like a lyre, or possibly a rectangular-framed harp.

Several of the details regarding Irish Gaelic history and social structure are also misleading. Christa refers to a "High King", and a "king at Cashel"; it's unlikely that there ever was a High King of Ireland, since the country was, by all accounts, divided into four provinces (Ulster, Connacht, Leinster, and Munster, to use their more modern names) under independent tribal authority. The records of the early Irish Church make St. Patrick's influence to be considerably more prominent than that of a "new arrival" - they would, in fact, have us believe that the entire island was converted to Christianity within a generation or two of his arrival in 423 C.E. It's important to remember, however, that Irish monks were hardly impartial observers of history, so this comment should be taken with a pillar of salt. There are no records of anything remotely resembling the harp school at Corca Duibne, although the area is to this day heavily populated by native Irish Gaelic speakers, and is one of the few places where traditional Irish culture is maintained ("traditional" meaning "pre-industrial").

The Ossianic ballads are a legitimate part of the Gaelic folk heritage. Finn mac

Cumhaill was the leader of a legendary band of fianna, or roving warriors; Oisin

was his son. The song that Christa and Kevin refer to as an Ossianic ballad, however, is certainly

not old enough for Chairiste to have learned in her youth: the first line begins with the word

"stiurad", the verb for "steering", which was imported into the Irish language during the Viking

invasions and settlements, along with nearly all the Gaelic words relating to boating and

seamanship. Viking Ireland would hardly have been the idyllic place that Christa suggested; the

Norwegians mainly used it as a battleground against their mortal foes, the Danes. The stanza that Christa

recites over Monica's grave, on the other hand, is old enough to be in context. It's assembled from

part of the Tain Bo Cualnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley), the most famous of the ancient

Irish epics. The lines come from a speech by the legendary Ulster warrior Cu Chulainn, who is

lamenting the fact that the fortunes of war have led him to kill his foster brother, Ferdia. In

Thomas Kinsella's translation (Oxford Press 1969), the lines read like this:

Thanks to Professor Colm O Baoill, Celtic Department, University of Aberdeen, for his assistance with this material. I doubt he knew what it was leading up to. =)

Some rock musicians featured prominently in Gossamer Axe:

The Blue Highway: A site chronicling the history of the blues.

PaddyNet's Island: A guide to Irish history and myth.

Ceolas Celtic Music Archive: A great resource for information about Celtic artists, traditional tunes and instruments, etc.

Gaelic Harps & Harpers In Ireland & Scotland

Harping: Some Web resources courtesy of Yahoo!

Denver: An information center.

For a different story involving myth and rock, check out the Mythos comic miniseries released by DC/Vertigo.

If you're interested in bands who play rock music in a pagan context, have a look at my pagan rock bands page. My Celtic rock bands page has links to artists who fuse rock music with traditional Celtic motifs.

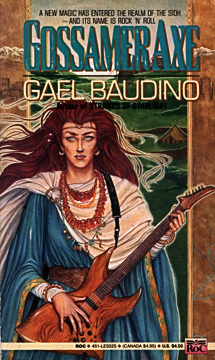

Back to the Gael Baudino Homepage