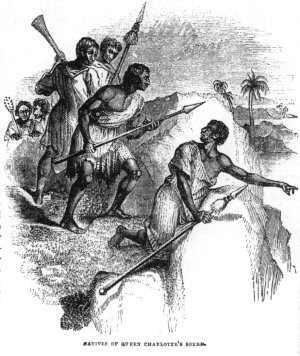

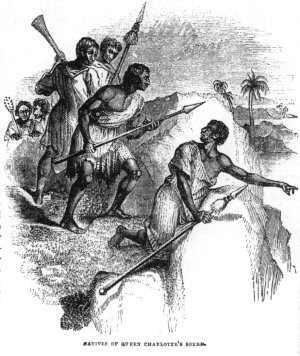

Captain Furneaux's Narrative of his proceedings in the Adventure, from the time he was separated from the Resolution, to his arrival in England; including Lieutenant Burney's report concerning the boat's crew, who were murdered by the inhabitants of Queen Charlotte's sound.

After a passage of fourteen days from Amsterdam, we made the coast of New Zealand near the Table Cape, and stood along-shore till we came as far as Cape Turnagain. The wind then began to blow strong at west, with heavy squalls and rain, which split many of our sails, and blew us off the coast for three days; in which time we parted company with the Resolution, and never saw her afterwards.

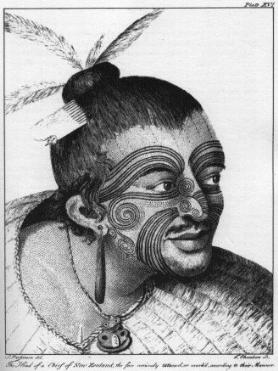

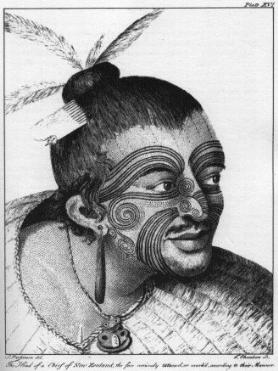

On the 4th of November, we again got in-shore, near Cape Palliser, and were visited by a number of the natives in their canoes, bringing a great quantity of cray-fish, which we bought of them for nails and Otaheite cloth. The next day it blew hard from W.N.W., which again drove us off the coast, and obliged us to bring to for two days; during which time it blew one continual gale of wind with heavy falls of sleet. By this time our decks were very leaky; our beds and bedding wet; and several of our people complaining of colds; so that we began to despair of ever getting into Charlotte Sound, or joining the Resolution. On the 6th, being to the north of the Cape, the wind at S.W. and blowing strong, we bore away for some bay to complete our water and wood, being in great want of both; having been at the allowance of one quart of water for some days past; and even that pittance could not be come at, above six or seven days longer. We anchored in Tolaga Bay on the 9th, in latitude 38° 21' S., longitude 178° 37' E. It affords good riding with the wind westerly, and regular soundings from eleven to five fathoms, stiff muddy ground across the bay for about two miles. It is open from N.N.E. to E.S.E. It is to be observed, easterly winds seldom blow hard on this shore, but when they do, they throw in a great sea; so that if it were not for a great undertow, together with a large river that empties itself in the bottom of the bay, a ship would not be able to ride here. Wood and water are easily to be had, except when it blows hard easterly. The natives here are the same as those a Charlotte Sound, but more numerous, and seemed settled, having regular plantations of sweet potatoes, and other roots, which are very good; and they have plenty of cray and other fish, which we bought of them for nails, beads, and other trifles, at an easy rate. In one of their canoes we observed the head of a woman lying in state, adorned with feathers and other ornaments. It had the appearance of being alive; but, on examination, we found it dry, being preserved with every feature perfect, and kept as the relic of some deceased relation. Having got about ten tons of water, and some wood, we sailed for Charlotte Sound on the 12th. We were no sooner out than the wind began to blow hard, dead on the shore, so that we could not clear the land on either tack. This obliged us to bear away again for the bay, where we anchored the next morning, and rode out a very heavy gale of wind at E. by S. which threw in a very great sea. We now began to fear we should never join the Resolution; having reason to believe she was in Charlotte Sound, and by this time ready for sea. We soon found it was with great difficulty we could get any water, owing to the swell setting in so strong; at last, however, we were able to go on shore, and got both wood and water.

On the 4th of November, we again got in-shore, near Cape Palliser, and were visited by a number of the natives in their canoes, bringing a great quantity of cray-fish, which we bought of them for nails and Otaheite cloth. The next day it blew hard from W.N.W., which again drove us off the coast, and obliged us to bring to for two days; during which time it blew one continual gale of wind with heavy falls of sleet. By this time our decks were very leaky; our beds and bedding wet; and several of our people complaining of colds; so that we began to despair of ever getting into Charlotte Sound, or joining the Resolution. On the 6th, being to the north of the Cape, the wind at S.W. and blowing strong, we bore away for some bay to complete our water and wood, being in great want of both; having been at the allowance of one quart of water for some days past; and even that pittance could not be come at, above six or seven days longer. We anchored in Tolaga Bay on the 9th, in latitude 38° 21' S., longitude 178° 37' E. It affords good riding with the wind westerly, and regular soundings from eleven to five fathoms, stiff muddy ground across the bay for about two miles. It is open from N.N.E. to E.S.E. It is to be observed, easterly winds seldom blow hard on this shore, but when they do, they throw in a great sea; so that if it were not for a great undertow, together with a large river that empties itself in the bottom of the bay, a ship would not be able to ride here. Wood and water are easily to be had, except when it blows hard easterly. The natives here are the same as those a Charlotte Sound, but more numerous, and seemed settled, having regular plantations of sweet potatoes, and other roots, which are very good; and they have plenty of cray and other fish, which we bought of them for nails, beads, and other trifles, at an easy rate. In one of their canoes we observed the head of a woman lying in state, adorned with feathers and other ornaments. It had the appearance of being alive; but, on examination, we found it dry, being preserved with every feature perfect, and kept as the relic of some deceased relation. Having got about ten tons of water, and some wood, we sailed for Charlotte Sound on the 12th. We were no sooner out than the wind began to blow hard, dead on the shore, so that we could not clear the land on either tack. This obliged us to bear away again for the bay, where we anchored the next morning, and rode out a very heavy gale of wind at E. by S. which threw in a very great sea. We now began to fear we should never join the Resolution; having reason to believe she was in Charlotte Sound, and by this time ready for sea. We soon found it was with great difficulty we could get any water, owing to the swell setting in so strong; at last, however, we were able to go on shore, and got both wood and water.

Whilst we lay here, we were employed about the rigging, which was much damaged by the constant gales of wind we had met with since we made the coast. We got the booms down on the decks, and having made the ship as snug as possible, sailed again on the 16th. After this we met with several gales of wind off the mouth of the strait, and continued beating backwards and forwards till the 30th, when we were so fortunate as to get a favourable wind, which we took every advantage of, and at last got safe into our desired port. We saw nothing of the Resolution, and began to doubt her safety; but on going ashore, we discovered the place where she had erected her tents; and, on an old stump of a tree in the garden, observed these words cut out, "Look underneath". There we dug, and soon found a bottle corked and waxed down, with a letter in it from Captain Cook, signifying their arrival on the 3d instant, and departure on the 24th; and that they intended spending a few days in the entrance of the straits to look for us. We immediately set about getting the ship ready for sea as fast as possible; erected our tents; sent the cooper on shore to repair the casks; and began to unstow the hold, to get at the bread that was in butts; but on opening them, found a great quantity of it entirely spoiled, and most part so damaged that we were obliged to fix our copper oven on shore to bake it over again, which undoubtedly delayed us a considerable time. Whilst we lay here, the inhabitants came on board as before, supplying us with fish, and other things of their own manufacture, which we bought of them for nails, &c., and appeared very friendly; though twice in the middle of the night they came to the tent, with an intention to steal, but were discovered before they could get anything into their possession.

On the 17th of December, having refitted the ship, completed our water and wood, and got everything ready for sea, we sent our large cutter, with Mr. Rowe, a midshipman, and the boat's crew, to gather wild greens for the ship's company, with orders to return that evening, as I intended to sail the next morning. But on the boat's not returning the same evening, nor the next morning, being under great uneasiness about her, I hoisted out the launch, and sent her, with the second lieutenant, Mr. Burney, manned with the boat's crew and ten marines, in search of her. My orders to Mr. Burney were, first to look well into East Bay, and then to proceed to Grass Cove, the place to which Mr. Rowe had been sent; and if he heard nothing of the boat there, to go farther up the Sound, and come back along the west shore. As Mr. Rowe had left the ship an hour before the time proposed, and in a great hurry, I was strongly persuaded that his curiosity had carried him into East Bay, none in our ship having ever been there or else, that some accident had happened to the boat, either by going adrift through the boat-keeper's negligence, or by being stove among the rocks. This was almost everybody's opinion; and on this supposition the carpenter's mate was sent in the launch, with some sheets of tin. I had not the least suspicion that our people had received any injury from the natives; our boats having frequently been higher up, and worse provided. How much I was mistaken too soon appeared; for Mr. Burney having returned about eleven o'clock the same night, made his report of a horrible scene indeed, which cannot be better described than in his own words, which now follow:

On the 18th we left the ship; and having a light breeze in our favour, we soon got round Long Island and within Long Point. I examined every cove on the larboard hand, as we went along, looking well all around with a spy-glass, which I took for that purpose. At half-past one we stopped at a beach, on the left-hand side going up East Bay, to boil some victuals, as we brought nothing but raw meat with us. Whilst we were cooking, I saw an Indian on the opposite shore running along a beach to the head of the bay. Our meat being dressed, we got into the boat and put off; and, in a short time, arrived at the head of this reach, where we saw an Indian settlement.

As we drew near, some of the Indians came down on the rocks, and waved for us to be gone; but seeing us disregarded them, they altered their notes. Here we found six large canoes hauled up on the beach, most of them double ones, and a great many people; though not so many as one might expect from the number of houses and size of the canoes. Leaving the boat's crew to guard the boat, I stepped ashore with the marines (the corporal and five men), and searched a good many of their houses; but found nothing to give me any suspicion. Three or four well-beaten paths led farther into the woods, where were many more houses; but the people continuing friendly, I thought it unnecessary to continue our search.

Coming down to the beach, one of the Indians had brought a bundle of hepatoos (long spears), but seeing I looked very earnestly at him, he put them on the ground, and walked about with seeming unconcern. Some of the people appearing to be frightened, I gave a looking-glass to one, and a large nail to another. From this place the bay ran, as nearly as I could guess, N.N.W. a good mile, where it ended in a long sandy beach. I looked all round with the glass, but saw no boat, canoe, or any sign of inhabitant. I therefore contented myself with firing some guns, which I had done in every cove as I went along.

I now kept close to the east shore, and came to another settlement, where the Indians invited us ashore. I inquired of them about the boat, but they pretended ignorance. They appeared very friendly here, and sold us some fish. Within an hour after we left this place, in a small beach adjoining to Grass Cove, we saw a very large double canoe just hauled up, with two men and a dog. The men, on seeing us, left their canoe, and ran up into the woods. This gave me reason to suspect I should here get tidings of the cutter. We went ashore, and searched the canoe, where we found one of the rullock-ports of the cutter, and some shoes, one of which was known to belong to Mr. Woodhouse, one of our midshipmen. One of the people, at the same time, brought me a piece of meat, which he took to be some of the salt meat belonging to the cutter's crew. On examining this, and smelling it, I found it was fresh. Mr. Fannin (the master), who was with me, supposed it was dog's flesh, and I was of the same opinion; for I still doubted their being cannibals. But we were soon convinced by the most horrid and undeniable proof.

A great many baskets (about twenty) lying on the beach, tied up, we cut them open. Some were full of roasted flesh, and some of fern-root, which serves them for bread. On farther search, we found more shoes, and a hand, which we immediately knew to have belonged to Thomas Hill, one of our forecastlemen, it being marked T.H. with an Otaheite tattoo-instrument. I went with some of the people a little way up the woods, but saw nothing else. Coming down again, there was a round spot, covered with fresh earth, about four feet diameter, where something had been buried. Having no spade, we began to dig with a cutlass; and in the meantime I launched the canoe with intent to destroy her; but seeing a great smoke ascending over the nearest hill, I got all the people into the boat, and made what haste I could to be with them before sunset.

On opening the next bay, which was Grass Cove, we saw four canoes, and a great many people on the beach, who, on our approach, retreated to a small hill, within a ship's length of the water side, where they stood talking to us. A large fire was on the top of the high land beyond the woods, from whence, all the way down the hill, the place was thronged like a fair. As we came in, I ordered a musquetoon to be fired at one of the canoes, suspecting they might be full of men lying down in the bottom; for they were all afloat, but nobody was seen in them. The savages on the little hill still kept hallooing and making signs for us to land. However, as soon as we got close in, we all fired. The first volley did not seem to affect them much; but on the second, they began to scramble away as fast as they could, some of them howling. We continued firing as long as we could see the glimpse of any of them through the bushes. Amongst the Indians were two very stout men, who never offered to move till they found themselves forsaken by their companions; and then they marched away with great composure and deliberation; their pride not suffering them to run. One of them, however, got a fall, and either lay there or crawled off on all-fours. The other got clear without any apparent hurt. I then landed with the marines, and Mr. Fannin staid to guard the boat.

On the beach were two bundles of celery, which had been gathered for loading the cutter. A broken oar was struck upright in the ground, to which the natives had tied their canoes; a proof that the attack had been made here. I then searched all along at the back of the beach, to see if the cutter was there. We found no boat, but instead of her, such a shocking scene of carnage and barbarity as can never be mentioned or thought of but with horror; for the heads, hearts, and lungs of several of our people were seen lying on the beach, and at a little distance, the dogs gnawing their entrails. Whilst we remained almost stupified on the spot, Mr. Fannin called to us that he heard the savages gathering together in the woods; on which I returned to the boat, and hauling alongside the canoes, we demolished three of them. Whilst this was transacting, the fire on the top of the hill disappeared; and we could hear the Indians in the woods at high words: I suppose quarrelling whether or no they should attack us, and try to save their canoes. It now grew dark: I therefore just stepped out, and looked once more behind the beach, to see if the cutter had been hauled up in the bushes; but seeing nothing of her, returned and put off. Our whole force would have been barely sufficient to have gone up the hill, and to have ventured with half (for half must have been left to guard the boat) would have been fool-hardiness.

As we opened the upper part of the Sound, we saw a very large fire about three or four miles higher up, which formed a complete oval, reaching from the top of a hill down almost to the water-side, the middle space being enclosed all round by the fire, like a hedge. I consulted with Mr. Fannin, and we were both of opinion that we could expect to reap no other advantage than the poor satisfaction of killing some more of the savages. At leaving Grass Cove, we had fired a general volley towards where we heard the Indians talking; but by going in and out of the boat, the arms had got wet, and four pieces missed fire. What was still worse, it began to rain; our ammunition was more than half expended, and we left six large canoes behind us in one place. With so many disadvantages, I did not think it worth while to proceed, where nothing could be hoped for but revenge. Coming between two round islands, situated to the southward of East Bay, we imagined we heard somebody calling; we lay on our oars and listened, but heard no more of it; we hallooed several times, but to little purpose; the poor souls were far enough out of hearing; and, indeed, I think it some comfort to reflect that, in all probability, every man of them must have been killed on the spot.

Thus far Mr. Burney's report; and, to complete the account of this tragical transaction, it may not be unnecessary to mention that the people in the cutter were, Mr. Rowe, Mr. Woodhouse, Francis Murphy, quarter-master; William Facey, Thomas Hill, Michael Bell, and Edward Jones, forecastle-men; John Cavenaugh and Thomas Milton, belonging to the after-guard; and James Sevilley, the captain's man; being ten in all. Most of these were of our very best seamen, the stoutest and most healthy people in the ship. Mr. Burney's party brought on board two hands; one belonging to Mr. Rowe, known by a hurt he had received on it; the other to Thomas Hill, as before mentioned; and the head of the captain's servant. These, with more of the remains, were tied in a hammock and thrown overboard, with ballast and shot sufficient to sink it. None of their arms nor clothes were found, except part of a pair of trowsers, a frock, and six shoes, no two of them being fellows.

I am not inclined to think this was any premeditated plan of these savages; for the morning Mr. Rowe left the ship, he met two canoes, which came down and staid all the forenoon in Ship Cove.

It might probably happen from some quarrel, which was decided on the spot; or the fairness of the opportunity might tempt them, our people being so incautious, and thinking themselves too secure. Another thing which encouraged the New Zealanders was they were sensible that a gun was not infallible, that they sometimes missed, and that, when discharged, they must be loaded before they could be used again, which time they knew how to take advantage of. After their success, I imagine there was a general meeting on the east side of the Sound. The Indians of Shag Cove were there; this we knew by a cock which was in one of the canoes, and by a long single canoe, which some of our people had seen four days before in Shag Cove, where they had been with Mr. Rowe in the cutter.

It might probably happen from some quarrel, which was decided on the spot; or the fairness of the opportunity might tempt them, our people being so incautious, and thinking themselves too secure. Another thing which encouraged the New Zealanders was they were sensible that a gun was not infallible, that they sometimes missed, and that, when discharged, they must be loaded before they could be used again, which time they knew how to take advantage of. After their success, I imagine there was a general meeting on the east side of the Sound. The Indians of Shag Cove were there; this we knew by a cock which was in one of the canoes, and by a long single canoe, which some of our people had seen four days before in Shag Cove, where they had been with Mr. Rowe in the cutter.

We were detained in the Sound by contrary winds four days after this melancholy affair happened, during which time we saw none of the inhabitants. What is very remarkable, I had been several times up in the same cove with Captain Cook, and never saw the least sign of an inhabitant, except some deserted towns, which appeared as if they had not been occupied for several years; and yet, when Mr. Burney entered the cove, he was of opinion there could not be less than fifteen hundred or two thousand people. I doubt not, had they been apprised of his coming, they would have attacked him. From these considerations I thought it imprudent to send a boat up again, as we were convinced there was not the least probability of any of our people being alive.

On the 23d, we weighed and made sail out of the Sound, and stood to the eastward to get clear of the Straits; which we accomplished the same evening, but were baffled for two or three days with light winds before we could clear the coast. We then stood to the S.S.E., till we got into the latitude of 56° S., without anything remarkable happening, having a great swell from the southward. At this time the winds began to blow strong from the S.W., and the weather to be very cold; and as the ship was low and deep laden, the sea made a continual breach over her, which kept us always wet; and by her straining, very few of the people were dry in bed or on deck, having no shelter to keep the sea from them. The birds were the only companions we had in this vast ocean; except, now and then, we saw a whale or porpoise, and sometimes a seal or two, and a few penguins. In the latitude of 58° S., longitude 213° E., we fell in with some ice, and every day saw more or less, we then standing to the E. We found a very strong current setting to the eastward; for by the time we were abreast of Cape Horn, being in the latitude of 61° S., the ship was ahead of our account eight degrees. We were very little more than a month from Cape Palliser, in New Zealand, to Cape Horn, which is an hundred and twenty-one degrees of longitude, and had continual westerly winds from S.W. to N.W., with a great sea following.

On opening some casks of peas and flour, that had been stowed on the coals, we found them very much damaged, and not eatable; so thought it most prudent to make for the Cape of Good Hope, but first to stand into the latitude and longitude of Cape Circumcision. After being to the eastward of Cape Horn, we found the winds did not blow so strong from the westward as usual, but came more from the north, which brought on thick foggy weather; so that for several days together we could not be able to get an observation, or see the least sign of the sun. This weather lasted above a month, being then among a great many islands of ice, which kept us constantly on the look-out for fear of running foul of them, and, being a single ship, made us more attentive. By this time our people began to complain of colds and pains in their limbs, which obliged me to haul to the northward to the latitude of 54° S.; but we still continued to have the same sort of weather, though we had oftener an opportunity of obtaining observations for the latitude. After getting into the latitude above mentioned, I steered to the east, in order, if possible, to find the land laid down by Bouvet. As we advanced to the east, the islands of ice became more numerous and dangerous, they being much smaller than they used to be, and the nights began to be dark.

On the 3d of March, being then in the latitude of 54° 4' S., longitude 13° E., which is the latitude of Bouvet's discovery, and half a degree to the eastward of it, and not seeing the least sign of land, either now or since we have been in this parallel, I gave over looking for it, and hauled away to the northward. As our last track to the southward was within a few degrees of Bouvet's discovery, in the longitude assigned to it, and about three or four degrees to the southward, should there be any land thereabout, it must be a very inconsiderable island. But I believe it was nothing but ice, as we, in our first setting out, thought we had seen land several times, but it proved to be high islands of ice at the back of the large fields; and as it was thick foggy weather when Mr. Bouvet fell in with it, he might very easily mistake them for land.

On the 7th, being in the latitude of 48° 30' S., longitude 14° 26' E., saw two large islands of ice. On the 17th, made the land of the Cape of Good Hope; and on the 19th, anchored in Table Bay, where we found Commodore Sir Edward Hughes, with his Majesty's ships Salisbury and Seahorse. I saluted the Commodore with thirteen guns, and, soon after, the garrison with the same number; the former returned the salute, as usual, with two guns less, and the latter with an equal number.

On the 24th, Sir Edward Hughes sailed with the Salisbury and Seahorse for the East Indies; but I remained, refitting the ship and refreshing my people, till the 16th of April, when I sailed for England; and on the 14th of July, anchored at Spithead.

© 1999 Michael Dickinson

[ Back ]

This page hosted by  Get your own Free Home Page

Get your own Free Home Page

On the 4th of November, we again got in-shore, near Cape Palliser, and were visited by a number of the natives in their canoes, bringing a great quantity of cray-fish, which we bought of them for nails and Otaheite cloth. The next day it blew hard from W.N.W., which again drove us off the coast, and obliged us to bring to for two days; during which time it blew one continual gale of wind with heavy falls of sleet. By this time our decks were very leaky; our beds and bedding wet; and several of our people complaining of colds; so that we began to despair of ever getting into Charlotte Sound, or joining the Resolution. On the 6th, being to the north of the Cape, the wind at S.W. and blowing strong, we bore away for some bay to complete our water and wood, being in great want of both; having been at the allowance of one quart of water for some days past; and even that pittance could not be come at, above six or seven days longer. We anchored in Tolaga Bay on the 9th, in latitude 38° 21' S., longitude 178° 37' E. It affords good riding with the wind westerly, and regular soundings from eleven to five fathoms, stiff muddy ground across the bay for about two miles. It is open from N.N.E. to E.S.E. It is to be observed, easterly winds seldom blow hard on this shore, but when they do, they throw in a great sea; so that if it were not for a great undertow, together with a large river that empties itself in the bottom of the bay, a ship would not be able to ride here. Wood and water are easily to be had, except when it blows hard easterly. The natives here are the same as those a Charlotte Sound, but more numerous, and seemed settled, having regular plantations of sweet potatoes, and other roots, which are very good; and they have plenty of cray and other fish, which we bought of them for nails, beads, and other trifles, at an easy rate. In one of their canoes we observed the head of a woman lying in state, adorned with feathers and other ornaments. It had the appearance of being alive; but, on examination, we found it dry, being preserved with every feature perfect, and kept as the relic of some deceased relation. Having got about ten tons of water, and some wood, we sailed for Charlotte Sound on the 12th. We were no sooner out than the wind began to blow hard, dead on the shore, so that we could not clear the land on either tack. This obliged us to bear away again for the bay, where we anchored the next morning, and rode out a very heavy gale of wind at E. by S. which threw in a very great sea. We now began to fear we should never join the Resolution; having reason to believe she was in Charlotte Sound, and by this time ready for sea. We soon found it was with great difficulty we could get any water, owing to the swell setting in so strong; at last, however, we were able to go on shore, and got both wood and water.

On the 4th of November, we again got in-shore, near Cape Palliser, and were visited by a number of the natives in their canoes, bringing a great quantity of cray-fish, which we bought of them for nails and Otaheite cloth. The next day it blew hard from W.N.W., which again drove us off the coast, and obliged us to bring to for two days; during which time it blew one continual gale of wind with heavy falls of sleet. By this time our decks were very leaky; our beds and bedding wet; and several of our people complaining of colds; so that we began to despair of ever getting into Charlotte Sound, or joining the Resolution. On the 6th, being to the north of the Cape, the wind at S.W. and blowing strong, we bore away for some bay to complete our water and wood, being in great want of both; having been at the allowance of one quart of water for some days past; and even that pittance could not be come at, above six or seven days longer. We anchored in Tolaga Bay on the 9th, in latitude 38° 21' S., longitude 178° 37' E. It affords good riding with the wind westerly, and regular soundings from eleven to five fathoms, stiff muddy ground across the bay for about two miles. It is open from N.N.E. to E.S.E. It is to be observed, easterly winds seldom blow hard on this shore, but when they do, they throw in a great sea; so that if it were not for a great undertow, together with a large river that empties itself in the bottom of the bay, a ship would not be able to ride here. Wood and water are easily to be had, except when it blows hard easterly. The natives here are the same as those a Charlotte Sound, but more numerous, and seemed settled, having regular plantations of sweet potatoes, and other roots, which are very good; and they have plenty of cray and other fish, which we bought of them for nails, beads, and other trifles, at an easy rate. In one of their canoes we observed the head of a woman lying in state, adorned with feathers and other ornaments. It had the appearance of being alive; but, on examination, we found it dry, being preserved with every feature perfect, and kept as the relic of some deceased relation. Having got about ten tons of water, and some wood, we sailed for Charlotte Sound on the 12th. We were no sooner out than the wind began to blow hard, dead on the shore, so that we could not clear the land on either tack. This obliged us to bear away again for the bay, where we anchored the next morning, and rode out a very heavy gale of wind at E. by S. which threw in a very great sea. We now began to fear we should never join the Resolution; having reason to believe she was in Charlotte Sound, and by this time ready for sea. We soon found it was with great difficulty we could get any water, owing to the swell setting in so strong; at last, however, we were able to go on shore, and got both wood and water. It might probably happen from some quarrel, which was decided on the spot; or the fairness of the opportunity might tempt them, our people being so incautious, and thinking themselves too secure. Another thing which encouraged the New Zealanders was they were sensible that a gun was not infallible, that they sometimes missed, and that, when discharged, they must be loaded before they could be used again, which time they knew how to take advantage of. After their success, I imagine there was a general meeting on the east side of the Sound. The Indians of Shag Cove were there; this we knew by a cock which was in one of the canoes, and by a long single canoe, which some of our people had seen four days before in Shag Cove, where they had been with Mr. Rowe in the cutter.

It might probably happen from some quarrel, which was decided on the spot; or the fairness of the opportunity might tempt them, our people being so incautious, and thinking themselves too secure. Another thing which encouraged the New Zealanders was they were sensible that a gun was not infallible, that they sometimes missed, and that, when discharged, they must be loaded before they could be used again, which time they knew how to take advantage of. After their success, I imagine there was a general meeting on the east side of the Sound. The Indians of Shag Cove were there; this we knew by a cock which was in one of the canoes, and by a long single canoe, which some of our people had seen four days before in Shag Cove, where they had been with Mr. Rowe in the cutter.