CJC: At eight o'clock in the evening of the 26th, we took our departure from Cape Palliser, and steered to the south, inclining to the east, having a favourable gale from the north-west and south-west: we daily saw some rock-weed, seals, Port-Egmont hens, albatrosses, pintadoes, and other peterels; and on the 2d of December, being in the latitude of 48° 23' S., longitude 179° 16' W., we saw a number of red-billed penguins, which remained about us for several days. On the 5th, being in the latitude 50° 17' S., longitude 179° 40' E., the variation was 18° 25' E. At half an hour past eight o'clock the next evening, we reckoned ourselves antipodes to our friends in London, consequently as far removed from them as possible.

CJC: At eight o'clock in the evening of the 26th, we took our departure from Cape Palliser, and steered to the south, inclining to the east, having a favourable gale from the north-west and south-west: we daily saw some rock-weed, seals, Port-Egmont hens, albatrosses, pintadoes, and other peterels; and on the 2d of December, being in the latitude of 48° 23' S., longitude 179° 16' W., we saw a number of red-billed penguins, which remained about us for several days. On the 5th, being in the latitude 50° 17' S., longitude 179° 40' E., the variation was 18° 25' E. At half an hour past eight o'clock the next evening, we reckoned ourselves antipodes to our friends in London, consequently as far removed from them as possible.

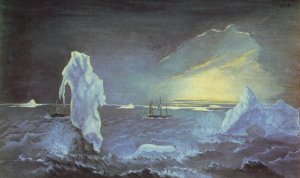

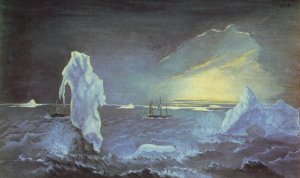

We fell in with several large islands on the 14th, and, about noon, with a quantity of loose ice, through which we sailed. Latitude 64° 55' S., longitude 163° 20' W. As we advanced to the S.E. by E., with a fresh gale at W., we found the number of ice islands increase fast upon us. Between noon and eight in the evening we saw but two, but before four o'clock in the morning of the 15th, we had passed seventeen, besides a quantity of loose ice which we ran through. At six o'clock we were obliged to haul to the north-east, in order to clear an immense field which lay to the south and south-east. The ice in most part of it lay close packed together; in other places there appeared partitions in the field, and a clear sea beyond it. However, I did not think it safe to venture through, as the wind would not permit us to return the same way that we must go in. Besides, as it blew strong, and the weather at times was exceedingly foggy, it was the more necessary for us to get clear of this loose ice, which is rather more dangerous than the great islands. It was not such ice as is usually found in bays or rivers, and near shore, but such as breaks off from the islands, and may not improperly be called parings of the large pieces, or the rubbish or fragments which fall off when the great islands break loose from the place where they are formed.

We had not stood long to the north-east before we found ourselves embayed by the ice, and were obliged to tack and stretch to the south-west, having the field or loose ice to the south, and many huge islands to the north. After standing two hours on this tack, the wind very luckily veering to the westward, we tacked, stretched to the north, and soon got clear of all the loose ice, but not before we had received several hard knocks from the larger pieces, which, with all our care, we could not avoid. After clearing one danger, we still had another to encounter; the weather remained foggy, and many large islands lay in our way; so that we had to luff for one, and bear up for another. One we were very near falling aboard of, and if it had happened, this circumstance would never have been related. These difficulties, together with the improbability of finding land farther south, and the impossibility of exploring it on account of the ice, if we should find any, determined me to get more to the north. At the time we last tacked, we were in the longitude of 159° 20' W., and in the latitude of 66° 0' S. Several penguins were seen on some of the ice islands, and a few antarctic peterels on the wing.

We continued to stand to the north, with a fresh gale at west, attended with thick snow showers till eight o'clock in the evening, when the wind abated, the sky began to clear up and, at six o'clock in the morning of the 16th, it fell calm. Four hours after, it was succeeded by a breeze at north-east, with which we stretched to the south-east, having thick hazy weather, with snow showers, and all our rigging coated with ice. In the evening, we attempted to take some out of the sea, but we were obliged to desist, the sea running too high, and the pieces being so large, that it was dangerous for the boat to come near them. The next morning, being the 17th, we succeeded better; for falling in with a quantity of loose ice, we hoisted out two boats, and by noon got on board as much as we could manage. We then made sail for the east, with a gentle breeze northerly, attended with snow and sleet, which froze to the rigging as it fell. At this time we were in the latitude of 64° 41' S., longitude 155° 44' W. The ice we took up proved to be none of the best, being chiefly composed of frozen snow, on which account it was porous, and had imbibed a good deal of salt water; but this drained off after lying a while on deck, and the water then yielded was fresh...

...The clear weather and the wind veering to north-west tempted me to steer south, which course we continued till seven in the morning of the 20th, when the wind changing to north-east, and the sky becoming clouded, we hauled up south-east. In the afternoon the wind increased to a strong gale, attended with a thick fog, snow, sleet, and rain, which constitutes the very worst of weather. Our rigging at this time was so loaded with ice that we had enough to do to get our top-sails down to double the reef. At seven o'clock in the evening, in the longitude of 147° 46', we came the second time within the antarctic or polar circle, continuing our course to the south-east till six o'clock the next morning. At that time, being in the latitude of 67° 5' S., all at once we got in among a cluster of very large ice islands, and a vast quantity of loose pieces; and, as the fog was exceedingly thick, it was with the utmost difficulty we wore clear of them. This done, we stood to the north-west till noon, when the fog being somewhat dissipated, we resumed our course again to the south-east. The ice islands we met with in the morning were very high and rugged, forming at their tops many peaks; whereas the most of those we had seen before were flat at top, and not so high, though many of them were between two and three hundred feet in height, and between two and three miles in circuit, with perpendicular cliffs or sides, astonishing to behold. Most of our winged companions had now left us, the grey albatrosses only remained, and instead of the other birds we were visited by a few antarctic peterels.

The 22nd we steered east-south-east with a fresh gale at north, blowing in squalls, one of which took hold of the mizen top-sail, tore it all to rags, and rendered it for ever after useless. At six o'clock in the morning, the wind veering toward the west, our course was east-northerly. At this time we were in the latitude of 67° 31', the highest we had yet been in, longitude 142° 54' west. We continued our course to the east by north till noon the 23rd, when, being in the latitude of 67° 12', longitude 138° 0', we steered south-east, having then twenty-three ice islands in sight from off the deck, and twice that number from the mast-head, and yet we could not see above two or three miles round us. At four o'clock in the afternoon, in the latitude of 67° 20', longitude 137° 12', we fell in with such a quantity of field or loose ice, as covered the sea in the whole extent from south to east, and was so thick and close as wholly to obstruct our passage. At this time, the wind being pretty moderate, and the sea smooth, we brought to at the outer edge of the ice, hoisted out two boats, and sent them to take some up. In the mean time, we laid hold of several large pieces alongside and got them on board with our tackle. The taking up ice proved such cold work, that it was eight o'clock by the time the boats had made two trips; when we hoisted them in, and made sail to the west, under double-reefed topsails and courses, with a strong gale at north, attended with snow and sleet, which froze to the rigging as it fell, making the ropes like wires, and the sails like boards or plates of metal. The sheaves also were frozen so fast in the the blocks, that it required our utmost efforts to get a topsail down and up; the cold so intense as hardly to be endured; the whole sea, in a manner covered with ice; a hard gale, and a thick fog.

Under all these unfavourable circumstances, it was natural for me to think of returning more to the north, seeing no probability of finding any land here, nor a possibility of getting farther south; and to have proceeded to the east, in this latitude, must have been wrong, not only on account of the ice, but because we must have left a vast space of sea to the north unexplored; a space of 24° of latitude, in which a large tract of land might have lain. Whether such a supposition was well grounded, could only be determined by visiting those parts.

JE: On the 25th (or Christmas Day) the Ice Islands was so numerous that I remember counting 300 from the Mast Head besides Pieces and Loose Ice, so that moderate as the Wind was, we had the greatest difficulty to keep the Ship clear of them. But had it come on a gale of wind we must inevitably have been lost.

On the 25th (or Christmas Day) the Ice Islands was so numerous that I remember counting 300 from the Mast Head besides Pieces and Loose Ice, so that moderate as the Wind was, we had the greatest difficulty to keep the Ship clear of them. But had it come on a gale of wind we must inevitably have been lost.

MY BIRTHDAY, 11th JAN. 1774. AGED 16. From hence we steered N.E. - wards up to 48° Latitude, then East for 10° Longitude, and afterwards due South. (In all this perilous Navigation, it must be remembered, we were a single Ship, so that should we be lost, or any thing happen to the Ship, we should never be heard of.)

At this time we all experienced a very severe mortification, for when we were steering East we had all taken it into our heads that we were going streight for Cape Horn, on our road home, for we began to find that our stock of Tea, Sugar, etc., began to go fast. Many hints were thrown out to Capt. Cook to this effect, but he only smiled and said nothing, for he was close and secret in his intentions at all times; not even his first Lieutenant knew, when we left a place where we should go to next. In this respect, as well as many others, he was the fit[test] Man in the World for such a Voyage. In this instance, all our hopes were blotted in a Minuit, for from steering East, at noon, Capt. Cook ordered the Ship to steer due South, to our utter astonishment, and had the effect for a moment of causing a buz in the Ship, but which soon subsided.

We continued steering to the South until we came into the Latitude of 71° 10' S., and Longitude 106° 54' W., when we were compleatly stopped by an extent of Field Ice as far as we could see from the Mast Heads, with many immence Mountains at a distance within. But whether there may be Land, within this continent of Ice, must, I believe, remain undesided for now.¹

Finding that it was not possible to proceed further, we stood for the North again, and well we did, for it soon came on to blow and snow, so that our sails and rigging were cased in Ice, an Inch thick - this was on the 30th of Jan. We continued going to the North a little Eastward at a great rate, into the Latitude of 38°.

But I will here observe that while amongst the Ice Islands we had the most miraculous escape from being every soul lost that ever Men had,² and thus it was: The officer of the Watch on deck, while the people was at dinner, had the imprudence to attempt going to windward of an Island of Ice, and from the Ship not going fast and his own fears making her keep too near the Wind, which made her go slower, he got so near that he could get neither one way nor the other, but appeared [to be] going right up on it, and it was twice as high as our Mast heads. In this situation he called up all hands, but to discribe the horrour depicted in every person's face at the awful situation in which we stood is impossible, no less in Cook's than our own, for no one but the officer and a few under his orders had noticed the situation of the Ship.

In this situation nothing could be done but to assist the Ship what little we could with the Sails, and wait the event with awful expectation of distruction. Capt. Cook ordered light spars to be got ready to push the Ship from the Island if she came so near, but had she come within their reach, we should have been overwhelmed in a moment and every soul drowned. The first stroke would have sent all our Masts overboard, and the next would have knocked the Ship to pieces and drowned us all. We were actualy within the backsurge of the Sea from the Island.

But most providentially for us she went clear, her stern just trailing within the Breakers from the Island. Certainly never men had a more narrow escape from the jaws of death.

Before I quit those cold regions, I must notice three things which at times afforded us much amusement, and to ordinary readers may appear curious: The first is that between the Latitudes of 60° and 70° on fine nights, the Aurora Australlis (or Southern Lights) would play in the Heavens in a most beautiful manner.

The second is, that we frequently heard in the night loud noises resembling the roaring of Cannon, and which proceeded from the Cracking or Splitting of Ice Islands. We have seen them once or twice roll over, tho they are generaly supposed to swim two thirds underwater.

The third is, that we frequently had the sun above the Horizon at Twelve o'clock at night, but not quite so bright as in the daytime. This will by Astronomers be easily understood, but to common readers it must seem curious.

During this route Cook was dangerously Ill, of a Bilious Complaint.³

CJC (FEB. 1774): I now came to a resolution to proceed to the north, and to spend the ensuing winter within the tropic, if I met with no employment before I came there. I was now well satisfied no continent was to be found in this ocean, but what must lie so far to the south as to be wholly inaccessible on account of ice; and that if one should be found in the Southern Atlantic Ocean, it would be necessary to have the whole summer before us to explore it. On the other hand, upon a supposition that there is no land there, we undoubtedly might have reached the Cape of Good Hope by April, and so have put an end to the expedition, so far as it related to the finding a continent; which indeed was the first object of the voyage. But for me at this time to have quitted this Southern Pacific Ocean, with a good ship expressly sent out on discoveries, a healthy crew, and not in want either of stores or of provisions, would have been betraying not only a want of Perseverance, but of judgment, in supposing the South Pacific Ocean to have been so well explored, that nothing remained to be done in it. This, however, was not my opinion; for although I had proved there was no continent but what must lie far to the south, there remained, nevertheless, room for very large islands in places wholly unexamined: and many of those which were formerly discovered are but imperfectly explored, and their situations as imperfectly known. I was besides of opinion that my remaining in this sea some time longer would be productive of improvements in navigation and geography, as well as other sciences. I had several times communicated my thoughts on this subject to Captain Furneaux; but as it then wholly depended on what we might meet with to the south, I could not give it in orders without running the risk of drawing us from the main object.

Since now nothing had happened to prevent me from carrying these views into execution, my intention was first to go in search of the land, said to have been discovered by Juan Fernandez, above a century ago, in about the latitude of 38°; if I should fail in finding this land, then to go in search of Easter Island or Davis's Land, whose situation was known with so little certainty that the attempts lately made to find it had miscarried. I next intended to get within the tropic, and then proceed to the west, touching at, and settling the situations of such islands as we might meet with till we arrived at Otaheite, where it was necessary I should stop to look for the Adventure. I had also thoughts of running as far west as the Tierra Austral del Espiritu Santo, discovered by Quiros, and which M. de Bougainville calls the Great Cyclades. Quiros speaks of this land as being large, or lying in the neighbourhood of large lands; and as this was a point which Bougainville had neither confirmed nor refuted, I thought it was worth clearing up. From this land my design was to steer to the south, and so back to the east, between the latitudes of 50° and 60°; intending if possible to be the length of Cape Horn in November next, when we should have the best part of the summer before us to explore the southern part of the Atlantic Ocean. Great as this design appeared to be, I, however, thought it possible to be executed; and when I came to communicate it to the officers, I had the satisfaction to find that they all heartily concurred in it. I should not do these gentlemen justice, if I did not take some opportunity to declare that they always showed the utmost readiness to carry into execution, in the most effectual manner, every measure I thought proper to take. Under such circumstances, it is hardly necessary to say that the seamen were always obedient and alert; and, on this occasion, they were so far from wishing the voyage at an end, that they rejoiced at the prospect of its being prolonged another year, and of soon enjoying the benefits of a milder climate.

I now steered north, inclining to the east, and in the evening we were overtaken by a furious storm at west-south-west, attended with snow and sleet. It came so suddenly upon us, that before we could take in our sails, two old top-sails, which we had bent to the yards, were blown to pieces, and the other sails much damaged. The gale lasted, without the least intermission, till the next morning, when it began to abate; it however continued to blow very fresh till noon on the 12th, when it ended in a calm... As we advanced to the north we felt a most sensible change in the weather. The 20th, at noon, we were in the latitude of 39° 58' S., longitude 94° 37' W. The day was clear and pleasant, and I may say the only summer's day we had had since we left New Zealand. The mercury in the thermometer rose to 66.

We still continued to steer to the north, as the wind remained in the old quarter; and the next day, at noon, we were in the latitude 37° 54' S., which was the same that Juan Fernandez's discovery is said to lie in. We, however, had not the least signs of any land lying in our neighbourhood. The next day at noon we were in latitude 36° 10' S., longitude 94° 56' W. Soon after, the wind veered to south-south-east, and enabled us to steer west-south-west, which I thought the most probable direction to find the land of which we were in search; and yet I had no hopes of succeeding, as we had a large hollow swell from the same point. We, however, continued this course till the 25th, when the wind having veered again round to the westward, I gave it up, and stood away to the north, in order to get into the latitude of Easter Island; our latitude at this time was 37° 52', longitude 101° 10' W.

I was now well assured that the discovery of Juan Fernandez, if any such was ever made, can be nothing but a small island; there being hardly room for a large land, as will fully appear by the tracks of Captain Wallis, Bougainville, of the Endeavour, and this of the Resolution. Whoever wants to see an account of the discovery in question, will meet with it in Mr. Dalrymple's Collection of Voyages to the South Seas. This gentleman places it under the meridian of 90°, where I think it cannot be; for M. de Bougainville seems to have run down under that meridian, and we had now examined the latitude in which it is said to lie, from the meridian of 94° to 101°. It is not probable it can lie to the east of 90°; because if it did, it must have been seen at one time or other by ships bound from the northern to the southern parts of America. Mr. Pengré, in a little treatise concerning the transit of Venus, published in 1768, gives some account of land having been discovered by the Spaniards in 1714, in the latitude of 38°, and 550 leagues from the coast of Chili, which is in the longitude of 110° or 111° W., and within a degree or two of my track in the Endeavour; so that this can hardly be its situation. In short, the only probable situation it can have must be about the meridian of 106° or 108° W.; and then it can only be a small isle, as I have already observed.

I was now taken ill of the bilious colic, which was so violent as to confine me to my bed; so that the management of the ship was left to Mr. Cooper, the first officer, who conducted her very much to my satisfaction. It was several days before the most dangerous symptoms of my disorder were removed... When I began to recover, a favourite dog belonging to Mr. Forster fell a sacrifice to my tender stomach. We had no other fresh meat whatever on board; and I could eat of this flesh, as well as broth made of it, when I could taste nothing else. Thus I received nourishment and strength from food which would have made most people in Europe sick; so true it is, that neccessity is governed by no law.

At eight o'clock in the morning on the 11th, land was seen, from the mast-head, bearing west, and at noon from the deck, extending from W. ¾ N to W. by S. about twelve leagues distant. I made no doubt that this was Davis's Land, or Easter Island, as its appearance from this situation corresponded very well with Wafer's account; and we expected to have seen the low sandy isle that Davis fell in with, which would have been a confirmation; but in this we were disappointed. At seven o'clock in the evening, the island bore from N. 62° W. to N. 87° W., about five leagues distant; in which situation we sounded, without finding ground, with a line of a hundred and forty fathoms. Here we spent the night, having alternately light airs and calms, till ten o'clock the next morning, when a breeze sprung up at west-south-west. With this we stretched in for the land; and, by the help of our glass, discovered people, and some of those colossian statues or idols mentioned by the authors of Roggewein's Voyage. At four o'clock in the afternoon, we were half a league south-south-east, and north-north-west of the north-east point of the island; and, on sounding, found thirty-five fathoms, a dark sandy bottom. I now tacked and endeavoured to get into what appeared to be a bay, on the west side of the point, or south-east side of the island; but before this could be accomplished, night came upon us, and we stood on and off under the land till the next morning, having soundings from seventy-five to a hundred and ten fathoms, the same bottom as before.

On the 13th, about eight o'clock in the morning, the wind, which had been variable most part of the night, fixed at south-east and blew in squalls, accompanied with rain, but it was not long before the weather became fair. As the wind now blew right on the south-east shore, which does not afford that shelter I at first thought, I resolved to look for anchorage on the west and north-west sides of the island. With this view, I bore up round the south point, off which lie two small islets, the one nearest the point high and peaked, and the other low and flattish. After getting round the point, and coming before a sandy beach, we found soundings, thirty and forty fathoms, sandy ground, and about one mile from the shore. Here a canoe conducted by two men came off to us. They brought with them a bunch of plantains, which they sent into the ship by a rope, and then they returned ashore. This gave us a good opinion of the islanders, and inspired us with hopes of getting some refreshments, which we were in great want of.

I continued to range along the coast till we opened the northern point of the isle without seeing a better anchoring-place than the one we had passed. We therefore tacked, and plied back to it; and, in the mean time, sent away the master in a boat to sound the coast. He returned about five o'clock in the evening, and soon after we came to an anchor, in thirty-six fathoms water, before the sandy beach above mentioned. As the master drew near the shore with the boat, one of the natives swam off to her, and insisted on coming aboard the ship, where he remained two nights and a day. The first thing he did after coming aboard, was to measure the length of the ship, by fathoming her from the taffrail to the stern; and as he counted the fathoms, we observed that he called the numbers by the same names that they do at Otaheite: nevertheless, his language was in a manner wholly unintelligible to all of us.

Having anchored too near the edge of the bank, a fresh breeze from the land, about three o'clock the next morning, drove us off it; on which the anchor was heaved up, and sail made to regain the bank again. While the ship was plying in, I went ashore, accompanied by some of the gentlemen, to see what the island was likely to afford us. We landed at the sandy beach, where some hundreds of the natives were assembled, and who were so impatient to see us, that many of them swam off to meet the boats. Not one of them had so much as a stick or weapon of any sort in their hands. After distributing a few trinkets amongst them, we made signs for something to eat; on which they brought down a few potatoes, plantains, and sugar-canes, and exchanged them for nails, looking-glasses, and pieces of cloth. We presently discovered that they were as expert thieves, and as tricking in their exchanges, as any people we had yet met with. It was with some difficulty we could keep the hats on our heads, but hardly possible to keep anything in our pockets, not even what themselves had sold us; for they would watch every opportunity to snatch it from us, so that we sometimes bought the same thing two or three times over, and after all did not get it.

Before I sailed from England, I was informed that a Spanish ship had visited this isle in 1769. Some signs of it were seen among the people now about us; one man had a pretty good broad-brimmed European hat on, another had a grego jacket, and another a red silk handkerchief. They also seemed to know the use of a musket, and to stand in much awe of it; but this they probably learnt from Roggewein, who, if we are to believe the authors of that voyage, left them sufficient tokens.

Near the place where we landed were some of those statues before mentioned, which I shall describe in another place. The country appeared barren and without wood; there were, nevertheless, several plantations of potatoes, plantains, and sugar-canes; we also saw some fowls, and found a well of brackish water. As these were articles we were in want of, and as the natives seemed not unwilling to part with them, I resolved to stay a day or two. With this view, I repaired on board, and brought the ship to an anchor in thirty-two fathoms water; the bottom, a fine dark sand. Our station was about a mile from the nearest shore... But the best mark for this anchoring-place is the beach; because it is the only one on this side of the island. In the afternoon we got on board a few casks of water, and opened a trade with the natives for such things as they had to dispose of. Some of the gentlemen also made an excursion into the country to see what it produced, and returned again in the evening, with the loss only of a hat, which one of the natives snatched off the head of one of the party.

Early next morning, I sent Lieutenants Pickersgill and Edgecumbe with a party of men, accompanied by several of the gentlemen, to examine the country. As I was not sufficiently recovered from my late illness to make one of the party, I was obliged to content myself with remaining at the landing-place among the natives. We had at one time a pretty brisk trade with them for potatoes, which we observed they dug up out of an adjoining plantation; but this traffic, which was very advantageous to us, was soon put a stop to by the owner (as we supposed) of the plantation coming down, and driving all the people out of it. By this we concluded that he had been robbed of his property, and that they were not less scrupulous of stealing from one another than from us, on whom they practised every little fraud they could think of, and generally with success; for we no sooner detected them in one, than they found out another. About seven o'clock in the evening, the party I had sent into the country returned, after having been over the greatest part of the island.

They left the beach about nine o'clock in the morning, and took a path which led across to the south-east side of the island, followed by a great crowd of the natives, who pressed much upon them. But they had not proceeded far, before a middle-aged man, punctured from head to foot, and his face painted with a sort of white pigment, appeared with a spear in his hand, and walked alongside of them, making signs to his countrymen to keep at a distance, and not to molest our people. When he had pretty well effected this, he hoisted a piece of white cloth on his spear, placed himself in the front, and led the way with his ensign of peace, as they understood it to be. For the greatest part of the distance across the ground had but a barren appearance, being a dry hard clay, and everywhere covered with stones; but, notwithstanding this, there were several large tracks planted with potatoes, and some plantain walks, but they saw no fruit on any of the trees. Towards the highest part of the south end of the island, the soil, which was a fine red earth, seemed much better, bore a longer grass, and was not covered with stones as in the other parts; but here they saw neither house nor plantation.

On the east side, near the sea, they met with three platforms of stone-work, or rather the ruins of them. On each had stood four of those large statues; but they were all fallen down from two of them, and also one from the third; all except one were broken by the fall, or in some measure defaced. Mr. Wales measured this one, and found it to be fifteen feet in length, and six feet broad over the shoulders. Each statue had on its head a large cylindric stone of a red colour, wrought perfectly round. The one they measured, which was not by far the largest, was fifty-two inches high, and sixty-six in diameter. In some, the upper corner of the cylinder was taken off in a sort of concave quarter-round, but in others the cylinder was entire.

From this place they followed the direction of the coast to the north-east, the man with the flag still leading the way... As they passed along, they observed on a hill a number of people collected together, some of whom had spears in their hands; but, on being called to by their countryman, they dispersed; except a few, amongst whom was one seemingly of some note. He was a stout, well-made man, with a fine open countenance; his face was painted, his body punctured, and he wore a better Ha Hou, or cloth, than the rest. He saluted them as he came up, by stretching out his arms with both hands clenched, lifting them over his head, opening them wide, and then letting them fall gradually down to his sides. To this man, whom they understood to be the chief of the island, their other friend gave his white flag; and he gave it to another, who carried it before them the remainder of the day.

They observed that the eastern side of the island was full of those gigantic statues so often mentioned; some placed in groups on platforms of masonry; others single, fixed only in the earth, and that not deep; and these latter are in general much larger than the others. Having measured one which had fallen down, they found it very near twenty-seven feet long, and upwards of eight feet over the breast or shoulders; and yet this appeared considerably short of the size of one they saw standing; its shade, a little past two o'clock, being sufficient to shelter all the party, consisting of near thirty persons, from the rays of the sun. Here they stopped to dine; after which they repaired to a hill, from whence they saw all the east and north shores of the isle, on which they could not see either bay or creek fit even for a boat to land in, nor the least signs of fresh water. What the natives brought them here was real salt water; but they observed that some of them drank pretty plentifully of it; so far will necessity and custom get the better of nature! On this account, they were obliged to return to the last well; where, after having quenched their thirst, they directed their route across the island towards the ship, as it was now four o'clock.

In a small hollow on the highest part of the island, they met with several such cylinders as are placed on the heads of the statues. Some of these appeared larger than any they had seen before; but it was now too late to stop to measure any of them. Mr. Wales, from whom I had this information, is of opinion that there had been a quarry here, whence these stones had formerly been dug, and that it would have been no difficult matter to roll them down the hill after they were formed. I think this a very reasonable conjecture, and have no doubt that it has been so. On the declivity of the mountain, towards the west, they met with another well; but the water was a very strong mineral, had a thick green scum on the top, and stunk intolerably. Necessity, however, obliged some to drink of it; but it soon made them so sick, that they threw it up the same way it went down.

In all this excursion, as well as the one made the preceding day, only two or three shrubs were seen. The leaf and seed of one (called by the natives Torromedo) were not much unlike those of the common vetch; but the pod was more like that of a tamarind in its size and shape. The seeds have a disagreeable bitter taste; and the natives, when they saw our people chew them, made signs to spit them out; from whence it was concluded that they think them poisonous. The wood is of a reddish colour, and pretty hard and heavy; but very crooked, small, and short, not exceeding six or seven feet in height. At the south-west corner of the island, they found another small shrub, whose wood was white and brittle, and in some measure, as also its leaf, resembling the ash. They also saw in several places the Otaheitean cloth plant; but it was poor and weak, and not above two and a half feet high at most. They saw not an animal of any sort, and but very few birds; nor indeed anything which can induce ships that are not in the utmost distress to touch at this island.

This account of the excursion I had from Mr. Pickersgill and Mr. Wales, men on whose veracity I could depend; and, therefore, I determined to leave the island the next morning, since nothing was to be obtained that could make it worth my while to stay longer; for the water which we had sent on board was not much better than if it had been taken up out of the sea. We had a calm till ten o'clock in the morning of the 16th, when a breeze sprung up at west, accompanied with heavy showers of rain, which lasted about an hour. The weather then clearing up, we got under sail, stood to sea, and kept plying to and fro, while an officer was sent on shore with two boats, to purchase such refreshments as the natives might have brought down; for I judged this would be the case, as they knew nothing of our sailing. The event proved that I was not mistaken; for the boats made two trips before night: when we hoisted them in, and made sail to the north-west with a light breeze at north north-east.

Further observations:

The inhabitants of this island do not seem to exceed six or seven hundred souls; and above two-thirds of those we saw were males. They either have but few females among them, or else many were restrained from making their appearance during our stay; for though we saw nothing to induce us to believe the men were of a jealous disposition, or the women afraid to appear in public, something of this kind was probably the case. In colour, features, and language, they bear such affinity to the people of the more western isles, that no one will doubt that they have had the same origin. It is extraordinary that the same nation should have spread themselves over all the isles in this vast ocean, from New Zealand to this island, which is almost one-fourth part of the circumference of the globe. Many of them have now no other knowledge of each other than what is preserved by antiquated tradition; and they have by length of time become, as it were, different nations, each having adopted some peculiar custom or habit, &c. Nevertheless, a careful observer will soon see the affinity each has to the other.

In general, the people of this isle are a slender race... Tattooing, or puncturing the skin, is much used here. The men are marked from head to foot, with figures all nearly alike; only some give them one direction, and some another, as fancy leads. The women are but little punctured; red and white paint is an ornament with them, as also with the men; the former is made of turmeric; but what composes the latter I know not. Their clothing is a piece or two of quilted cloth about six feet by four, or a mat. One piece wrapped round their loins, and another over their shoulders, make a complete dress. But the men, for the most part, are in a manner naked, wearing nothing but a slip of cloth betwixt their legs, each end of which is fastened to a cord or belt they wear round the waist. Their cloth is made of the same materials as at Otaheite, viz. of the bark of the cloth-plant; but as they have but little of it, our Otaheitean cloth, or indeed any sort of it, came here to a good market.

Both men and women have very large holes, or rather slits, in their ears, extended to near three inches in length. They sometimes turn this slit over the upper part, and then the ear looks as if the flap was cut off. The chief ear ornaments are the white down of feathers, and rings, which they wear in the inside of the hole, made of some elastic substance, rolled up like a watch-spring. I judged this was to keep the hole at its utmost extension. I do not remember seeing them wear any other ornaments, excepting amulets made of bone or shells. As harmless and friendly as these people seem to be, they are not without offensive weapons, such as short wooden clubs and spears; which latter are crooked sticks about six feet long, armed at one end with pieces of flint. They have also a weapon made of wood, like the Patoo patoo of New Zealand.

The gigantic statues so often mentioned are not, in my opinion, looked upon as idols by the present inhabitants, whatever they might have been in the days of the Dutch; at least, I saw nothing that could induce me to think so. On the contrary, I rather suppose that they are burying-places for certain tribes or families. I, as well as some others, saw a human skeleton lying in one of the platforms, just covered with stones. Some of these platforms of masonry are thirty or forty feet long, twelve or sixteen broad, and from three to twelve in height; which last in some measure depends on the nature of the ground. For they are generally at the brink of the bank facing the sea, so that this face may be ten or twelve feet or more high, and the other may not be above three or four. They are built, or rather faced, with hewn stones of a very large size; and the workmanship is not inferior to the best plain piece of masonry we have in England. They use no sort of cement; yet the joints are exceedingly close, and the stones morticed and tenanted one into another, in a very artful manner. The side walls are not perpendicular, but inclining a little inwards, in the same manner that breast-works, &c., are built in Europe: yet had not all this care, pains, and sagacity been able to preserve these curious structures from the ravages of all-devouring time. The statues, or at least many of them, are erected on these platforms, which serve as foundations. They are, as near as we could judge, about half length, ending in a sort of stump at the bottom, on which they stand. The workmanship is rude, but not bad; nor are the features of the face ill formed, the nose and chin in particular; but the ears are long beyond proportion; and, as to the bodies, there is hardly anything like a human figure about them.

I had an opportunity of examining only two or three of these statues, which are near the landing-place; and they were of a grey stone, seemingly of the same sort as that with which the platforms were built. But some of the gentlemen who travelled over the island, and examined many of them, were of opinion that the stone of which they were made was different from any other they saw on the island, and had much the appearance of being factitious. We could hardly conceive how these islanders, wholly unacquainted with any mechanical power, could raise such stupendous figures, and afterwards place the large cylindric stones, before mentioned, upon their heads. The only method I can conceive, is by raising the upper end by little and little, supporting it by stones as it is raised, and building about it till they got it erect; thus a sort of mount, or scaffolding, would be made, upon which they might roll the cylinder, and place it upon the head of the statue, and then the stones might be removed from about it. But if the stones are factitious, the statues might have been put together on the place in their present position, and the cylinder put on by building a mount round them as above mentioned. But, let them have been made and set up, by this or any other method, they must have been a work of immense time, and sufficiently show the ingenuity and perseverance of the islanders in the age in which they were built; for the present inhabitants have most certainly had no hand in them, as they do not even repair the foundations of those which are going to decay. They give different names to them, such as Gotomoara, Marapate, Kanaro, Gowaytoo-goo, Matta Matta, &c. &c., to which they sometimes prefix the word Moi, and sometimes annex Areekee. The latter signifies chief, and the former, burying, or sleeping-place, as well as we could understand. Besides the monuments of antiquity, which were pretty numerous, and nowhere but on or near the sea-coast, there were many little heaps of stones piled up in different places, along the coast. Two or three of the uppermost stones in each pile were generally white; perhaps always so, when the pile is complete. It will hardly be doubted that these piles of stone had a meaning. Probably they might mark the place where people had been buried, and serve instead of the large statues.

The working-tools of these people are but very mean, and, like those of all the other islanders we have visited in this ocean, made of stone, bone, shells, &c. They set but little value on iron, or iron tools, which is the more extraordinary as they know their use; but the reason may be their having but little occasion for them.

From Easter Island to Melanesia

¹ No ship has ever since been further South on this longitude.

¹ No ship has ever since been further South on this longitude.

² This incident had actually taken place on December 15, 1773, and was noted by Cook in his journal (Beaglehole ed., p.304) with the comment "According to the old proverb a miss is as good as a mile, but our situation requires more misses than we can expect..."

³ In the book 'Captain James Cook and his Times' (ed. R. Fisher and H. Johnson, Vancouver, 1979. p.155), Sir James Watt considers that the symptoms suffered by Cook during this severe illness - vomiting, constipation and hiccoughs - give a "classical picture of acute intestinal obstruction". The obstruction may have been caused by a gallbladder infection, or, as Watt suggests, a roundworm infestation of the intestine.

© 1999 Michael Dickinson

[ Home | The 1st Voyage | The 2nd Voyage | The 3rd & Final Voyage | Next ]

This page hosted by  Get your own Free Home Page

Get your own Free Home Page

CJC: At eight o'clock in the evening of the 26th, we took our departure from Cape Palliser, and steered to the south, inclining to the east, having a favourable gale from the north-west and south-west: we daily saw some rock-weed, seals, Port-Egmont hens, albatrosses, pintadoes, and other peterels; and on the 2d of December, being in the latitude of 48° 23' S., longitude 179° 16' W., we saw a number of red-billed penguins, which remained about us for several days. On the 5th, being in the latitude 50° 17' S., longitude 179° 40' E., the variation was 18° 25' E. At half an hour past eight o'clock the next evening, we reckoned ourselves antipodes to our friends in London, consequently as far removed from them as possible.

CJC: At eight o'clock in the evening of the 26th, we took our departure from Cape Palliser, and steered to the south, inclining to the east, having a favourable gale from the north-west and south-west: we daily saw some rock-weed, seals, Port-Egmont hens, albatrosses, pintadoes, and other peterels; and on the 2d of December, being in the latitude of 48° 23' S., longitude 179° 16' W., we saw a number of red-billed penguins, which remained about us for several days. On the 5th, being in the latitude 50° 17' S., longitude 179° 40' E., the variation was 18° 25' E. At half an hour past eight o'clock the next evening, we reckoned ourselves antipodes to our friends in London, consequently as far removed from them as possible.