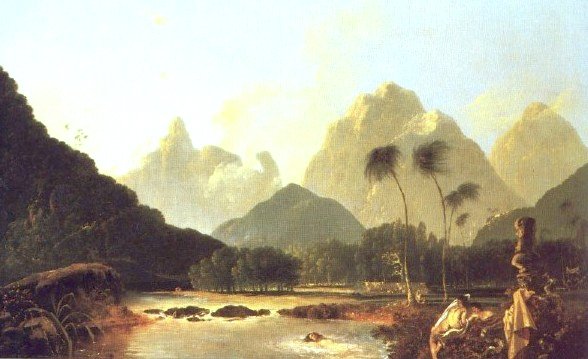

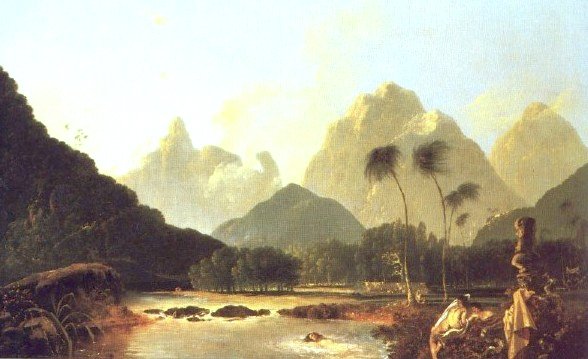

"Tahiti Revisited" by William Hodges.

CJC:

When we first drew near the island, several canoes came off to the ship, each conducted by two or three men; but as they were common fellows, Omai took no particular notice of them, nor they of him. They did not even seem to perceive that he was one of their countrymen, although they conversed with him for some time. At length, a chief whom I had known before, named Ootee, and Omai's brother-in-law, who chanced to be now at this corner of the island, and three or four more persons, all of whom knew Omai before he embarked with Captain Furneaux, came on board. Yet there was nothing either tender or striking in their meeting. On the contrary, there seemed to be a perfect indifference on both sides, till Omai having taken his brother down into the cabin, opened the drawer where he kept his red feathers and gave him a few. This being presently known amongst the rest of the natives upon deck, the face of affairs was entirely turned, and Ootee, who would hardly speak to Omai before, now begged that they might be tayos [friends], and exchange names. Omai accepted of the honour, and confirmed it with a present of red feathers; and Ootee, by way of return, sent ashore for a hog. But it was evident to every one of us, that it was not the man, but his property they were in love with. Had he not shown them his treasure of red feathers, which is the commodity in greatest estimation at the island, I question much whether they would have bestowed even a cocoa-nut upon him. Such was Omai's first reception among his countrymen. I own I never expected it would be otherwise; but still, I was in hopes that the valuable cargo of presents with which the liberality of his friends in England had loaded him, would be the means of raising him into consequence, and of making him respected, and even courted by the first persons throughout the extent of the Society Islands. This could not but have happened, had he conducted himself with any degree of prudence; but instead of it, I am sorry to say, that he paid too little regard to the repeated advice of those who wished him well, and suffered himself to be duped by every designing knave.

From the natives who came off to us in the course of this day, we learnt that two ships had twice been in Oheitepeha Bay since my last visit to this island in 1774, and that they had left animals there, such as we had on board. But, on farther inquiry, we found they were only hogs, dogs, goats, one bull, and the male of some other animal, which, from the imperfect description now given us, we could not find out. They told us that these ships had come from a place called Reema; by which we guessed that Lima, the capital of Peru, was meant, and that these late visitors were Spaniards. We were informed, that the first time they came, they built a house and left four men behind them, viz. two priests, a boy or servant, and a fourth person called Mateema, who was much spoken of at this time; carrying away with them, when they sailed, four of the natives; that in about ten months, the same two ships returned, bringing back two of the islanders, the other two having died at Lima; and that, after a short stay, they took away their own people; but that the house which they had built was left standing.

The important news of red feathers being on board our ships, having been conveyed on shore by Omai's friends, day had no sooner begun to break next morning, than we were surrounded by a multitude of canoes crowded with people, bringing hogs and fruit to market. At first, a quantity of feathers, not greater than what might be got from a tom-tit, would purchase a hog of forty or fifty pounds' weight. But as almost everybody in the ships was possessed of some of this precious article in trade, it fell in its value above five hundred per cent, before night. However, even then, the balance was much in our favour; and red feathers continued to preserve their superiority over every other commodity. Some of the natives would not part with a hog, unless they received an axe in exchange; but nails, and beads and other trinkets, which, during our former voyages had so great a run at this island, were now so much despised, that few would deign so much as to look at them.

There being but little wind all the morning, it was nine o'clock before we could get to an anchor in the bay; where we moored with two bowers. Soon after we had anchored, Omai's sister came on board to see him. I was happy to observe, that, much to the honour of them both, their meeting was marked with expressions of the tenderest affection, easier to be conceived than to be described. This moving scene having closed, and the ship being properly moored, Omai and I went ashore. I left him in the midst of a number of people who had gathered round, and went to take a view of the house said to be built by the strangers who had lately been here. I found it standing at a small distance from the beach. The wooden materials of which it was composed seemed to have been brought hither ready prepared, to be set up occasionally, for all the planks were numbered. It was divided into two small rooms; and in the inner one were, a bedstead, a table, a bench, some old hats, and other trifles, of which the natives seemed to be very careful, as also of the house itself, which had suffered no hurt from the weather, a shed having been built over it. There were scuttles all around which served as air-holes; and, perhaps, they were also meant to fire from, with muskets, if ever this should be found necessary. At a little distance from the front stood a wooden cross, on the transverse part of which was cut the following inscription:

CHRISTUS VINCIT.

CHRISTUS VINCIT.And, on the perpendicular part (which confirmed our conjecture, that the two ships were Spanish),

On the other side of the post, I preserved the memory of the prior visits of the English, by inscribing,

The natives pointed out to us, near the foot of the cross, the grave of the commodore of the two ships, who had died here, while they lay in the bay the first time. His name, as they pronounced it, was Oreede. Whatever the intentions of the Spaniards in visiting this island might be, they seemed to have taken great pains to ingratiate themselves with the inhabitants, who, upon every occasion, mentioned them with the strongest expressions of esteem and veneration.

When I returned from viewing the house and cross erected by the Spaniards, I found Omai holding forth to a large company; and it was with some difficulty that he could be got away, to accompany me on board; where I had an important affair to settle.

As I knew that Otaheite and the neighbouring islands could furnish us with a plentiful supply of cocoa-nuts, the liquor of which is an excellent succedaneum for any artificial beverage, I was desirous of prevailing upon my people to consent to be abridged, during our stay here, of their stated allowance of spirits to mix with water. But as this stoppage of a favourite article, without assigning some reason, might have occasioned a general murmur, I thought it most prudent to assemble the ship's company, and to make known to them the intent of the voyage, and the extent of our future operations. To induce them to undertake which with cheerfulness and perseverance, I took notice of the rewards offered by Parliament to such of his Majesty's subjects as shall first discover a communication between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, in any direction whatever, in the northern hemisphere: and also to such as shall first penetrate beyond the 89th degree of northern latitude. I made no doubt, I told them, that I should find them willing to co-operate with me in attempting, as far as might be possible, to become entitled to one or both these rewards; but that, to give us the best chance of succeeding, it would be necessary to observe the utmost economy in the expenditure of our stores and provisions, particularly the latter, as there was no probability of getting a supply anywhere after leaving these islands. I strengthened my argument, by reminding them, that our voyage must last at least a year longer than had been originally supposed, by our having already lost the opportunity of getting to the North this summer. I begged them to consider the various obstructions and difficulties we might still meet with, and the aggravated hardships they would labour under, if it should be found necessary to put them to short allowance of any species of provisions in a cold climate. For these very substantial reasons, I submitted to them, whether it would not be better to be prudent in time, and rather than to run the risk of having no spirits left, when such a cordial would be most wanted, to consent to be without their grog now, when we had so excellent a liquor as that of cocoa-nuts to substitute in its place; but that, after all, I left the determination entirely to their own choice. I had the satisfaction to find, that this proposal did not remain a single moment under consideration; being unanimously approved of, immediately, without any objection. I ordered Captain Clerke to make the same proposal to his people; which they also agreed to. Accordingly, we stopped serving grog, except on Saturday nights, when the companies of both ships had full allowance of it, that they might drink the healths of their female friends in England; lest these, amongst the pretty girls of Otaheite, should be wholly forgotten.

The next day we began some necessary operations; to inspect the provisions that were in the main and fore hold; to get the casks of beef and pork, and the coals, out of the ground tier; and to put some ballast in their place. The caulkers were set to work to caulk the ship, which she stood in great need of; having, at times, made much water on our passage from the Friendly Islands. I also put on shore the bull, cows, horses, and sheep, and appointed two men to look after them while grazing; for I did not intend to leave any of them at this part of the island. During the two following days, it hardly ever ceased raining. The natives, nevertheless, came to us from every quarter, the news of our arrival having rapidly spread. Waheiadooa, though at a distance, had been informed of it; and, in the afternoon of the 16th, a chief, named Etorea, under whose tutorage he was, brought me two hogs as a present from him; and acquainted me, that he himself would be with us the day after. And so it proved; for I received a message from him the next morning, notifying his arrival, and desiring I would go ashore to meet him. Accordingly, Omai and I prepared to pay him a formal visit. On this occasion, Omai, assisted by some of his friends, dressed himself, not after the English fashion, nor that of Otaheite, nor that of Tongataboo, nor in the dress of any country upon earth, but in a strange medley of all that he was possessed of.

Thus equipped, on our landing, we first visited Etary; who, carried on a hand-barrow, attended us to a large house, where he was set down; and we seated ourselves on each side of him. I caused a piece of Tongataboo cloth to be spread out before us, on which I laid the presents I intended to make. Presently the young chief came, attended by his mother, and several principal men, who all seated themselves, at the other end of the cloth, facing us. Then a man who sat by me, made a speech, consisting of short and separate sentences; part of which was dictated by those about him. He was answered by one from the opposite side, near the chief. Etary spoke next; then Omai; and both of them were answered from the same quarter. These orations were entirely about my arrival, and connexions with them. The person who spoke last told me, amongst other things, that the men of Reema, that is, the Spaniards, had desired them not to suffer me to come into Oheitepeha Bay, if I should return any more to the island, for that it belonged to them; but that they were so far from paying any regard to this request, that he was authorised now to make a formal surrender of the province of Tiaraboo to me, and of every thing in it; which marks very plainly, that these people are no strangers to the policy of accommodating themselves to present circumstances. At length, the young chief was directed, by his attendants, to come and embrace me; and, by way of confirming this treaty of friendship, we exchanged names. The ceremony being closed, he and his friends accompanied me on board to dinner.

Omai had prepared a maro, composed of red and yellow feathers, which he intended for Otoo, the king of the whole island; and, considering where we were, it was a present of very great value. I said all that I could to persuade him not to produce it now, wishing him to keep it on board till an opportunity should offer of presenting it to Otoo, with his own hands. But he had too good an opinion of the honesty and fidelity of his countrymen to take my advice. Nothing would serve him but to carry it ashore, on this occasion, and to give it to Waheiadooa, to be by him forwarded to Otoo, in order to its being added to the royal maro. He thought, by this management, that he should oblige both chiefs; whereas he highly disobliged the one, whose favour was of the most consequence to him, without gaining any reward from the other. What I had foreseen happened. For Waheiadooa kept the maro for himself, and only sent to Otoo a very small piece of feathers; not the twentieth part of what belonged to the magnificent present. On the 19th, this young chief made me a present of ten or a dozen hogs, a quantity of fruit, and some cloth. In the evening we played off some fire-works, which both astonished and entertained the numerous spectators.

This day, some of our gentlemen, in their walks, found, what they were pleased to call, a Roman Catholic chapel. Indeed, from their account, this was not to be doubted; for they described the altar and every other constituent part of such a place of worship. However, as they mentioned, at the same time, that two men, who had the care of it, would not suffer them to go in, I thought that they might be mistaken, and had the curiosity to pay a visit to it myself. The supposed chapel proved to be a toopapaoo, in which the remains of the late Waheiadooa lay, as it were, in state. It was in a pretty large house, which was inclosed with a low palisade. The toopapaoo was uncommonly neat, and resembled one of those little houses, or awnings, belonging to their large canoes. Perhaps it had originally been employed for that purpose. It was covered, and hung round, with cloth and mats of different colours, so as to have a pretty effect. There was one piece of scarlet broad cloth, four or five yards in length, conspicuous among the other ornaments; which, no doubt, had been a present from the Spaniards. This cloth, and a few tassels of feathers, which our gentlemen supposed to be silk, suggested to them the idea of a chapel; for whatever else was wanting to create a resemblance, their imagination supplied; and if they had not previously known that there had been Spaniards lately here, they could not possibly have made the mistake. Small offerings of fruit and roots seemed to be daily made at this shrine, as some pieces were quite fresh. These were deposited upon a whatta, or altar, which stood without the palisades; and within these we were not permitted to enter. Two men constantly attended, night and day, not only to watch over the place, but also to dress and undress the toopapaoo. For when I first went to survey it, the cloth and its appendages were all rolled up; but, at my request, the two attendants hung it out in order, first dressing themselves in clean white robes. They told me, that the chief had been dead twenty months.

Having taken in a fresh supply of water, and finished all our other necessary operations, on the 22d, I brought off the cattle and sheep, which had been put on shore here to graze; and made ready for sea. In the evening of the 23d, while the ships were unmooring, Omai and I landed, to take leave of the young chief. While we were with him, one of those enthusiastic persons, whom they call Eatooas, from a persuasion that they are possessed with the spirit of the Divinity, came and stood before us. He had all the appearance of a man not in his right senses; and his only dress was a large quantity of plantain leaves, wrapped round his waist. He spoke in a low, squeaking voice, so as hardly to be understood; at least, not by me. But Omai said, that he comprehended him perfectly, and that he was advising Waheiadooa not to go with me to Matavai; an expedition which I had never heard he intended, nor had I ever made such a proposal to him. The Eatooa also foretold, that the ships would not get to Matavai that day. But in this he was mistaken; though appearances now rather favoured his prediction, there not being a breath of wind in any direction. While he was prophesying, there fell a very heavy shower of rain, which made every one run for shelter but himself, who seemed not to regard it. He remained squeaking by us about half an hour, and then retired. No one paid any attention to what he uttered; though some laughed at him. I asked the chief, what he was, whether an Earee, or Towtow? and the answer I received was, that he was taato eno; that is, a bad man. And yet, notwithstanding this, and the little notice any of the natives seemed to take of the mad prophet, superstition has so far got the better of their reason, that they firmly believe such persons to be possessed with the spirit of the Eatooa. Omai seemed to be very well instructed about them. He said, that, during the fits that came upon them, they knew nobody, not even their most intimate acquaintances; and that, if any one of them happens to be a man of property, he will very often give away every moveable he is possessed of, if his friends do not put them out of his reach; and, when he recovers, will inquire what had become of those very things, which he had, but just before distributed; not seeming to have the least remembrance of what he had done while the fit was upon him.

As soon as I got on board, a light breeze springing up at east, we got under sail, and steered for Matavai Bay; where the Resolution anchored the same evening. But the Discovery did not get in till the next morning; so that half of the man's prophecy was fulfilled.

© 2000 Michael Dickinson