Introduction by Guy Pocock

Introduction by Guy Pocock ![]() (1941):

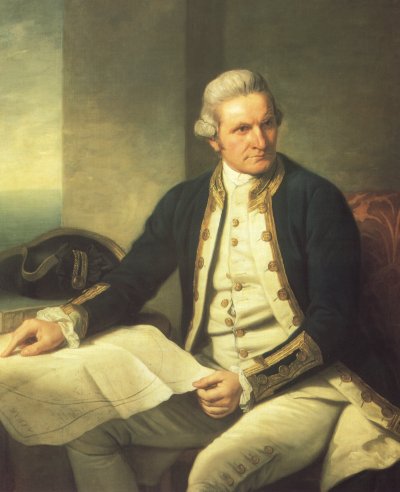

(1941): ![]() James Cook was born on the 27th October 1728, of humble stock, in the little Yorkshire village of Marton. The cottage in which James was born has long since been demolished, and nothing now remains but vestiges of the pump. But his memory is kept green by a flourishing Captain Cook Memorial School founded in 1850. The Cooks soon moved to the village of Great Ayton, where they lived in a cottage that still stands by the stream, while James's father built a more commodious cottage to house his growing family. Of this cottage nothing remains - in England, though a small obelisk in an enclosed space marks the plot where it stood. It was taken down stone by stone and brick by brick and transported to Australia where it has been rebuilt in Melbourne public gardens - one of Australia's most cherished relics.

James Cook was born on the 27th October 1728, of humble stock, in the little Yorkshire village of Marton. The cottage in which James was born has long since been demolished, and nothing now remains but vestiges of the pump. But his memory is kept green by a flourishing Captain Cook Memorial School founded in 1850. The Cooks soon moved to the village of Great Ayton, where they lived in a cottage that still stands by the stream, while James's father built a more commodious cottage to house his growing family. Of this cottage nothing remains - in England, though a small obelisk in an enclosed space marks the plot where it stood. It was taken down stone by stone and brick by brick and transported to Australia where it has been rebuilt in Melbourne public gardens - one of Australia's most cherished relics.

At Ayton James attended Mr. Pullen's little school where he seems to have shown a flair for figures. He also owed much kindness to the people of the Manor. But it was soon time for him to earn his living; and his father apprenticed him to a Mr. Sanderson who kept a general stores at Staithes. (The name Sanderson occurs on tombstones in Ayton churchyard.) So James went off to the astonishing little harbour-town of Staithes which lies tucked in at the base of the cliffs and is reached by one precipitous road. There he worked all day in an atmosphere of haberdashery and groceries, slept under the counter at night, and in his scant free time listened to the tales of sailormen down by the tiny harbour, or outside the 'Cod and Lobster'.

James stood it for a year and a half. One story is that he got up early one morning and ran away to sea, thus breaking his indentures. Others say it is more likely that Mr. Sanderson, realizing that the life of shop-boy was no life for James, came to a kind and amicable arrangement. What we do know is that James walked the thirteen miles over the cliff to Whitby, found a collier lying alongside the quay, and offered his services to the mate. And the mate, liking the look of the lad, sent him off to see the owners of the little collier fleet - the Walker Brothers, Quakers, of Whitby. James was appointed, and the life of his choice had begun. They plied chiefly between Newcastle and London; but it is certain that they also visited Norway, the Baltic, and Ireland.

Years passed, and James won his mate's certificate; and there is no doubt he would have been appointed skipper of one of the collier fleet had not the Seven Years War broken out. After much thought Cook decided to volunteer, and was sent out to America. At once he made his mark, and before long he found himself master of a king's ship, the Mercury, and was sent to join Admiral Saunders who was besieging Quebec. There he was given the difficult and dangerous work of charting the channel of the St. Lawrence right up to the French lines, and he did it superlatively well. He worked at night in peril of his life - on one occasion Indians leapt on to the stern of his boat as he jumped off the bows - but the work was done, and found to be absolutely reliable. But how he found time, or obtained the necessary books, to make himself an expert surveyor and cartographer, and to study mathematics and astronomy to the point of contributing papers to the Royal Society on abstruse mathematical problems such as finding location by the moon, is a mystery that will never now be explained.

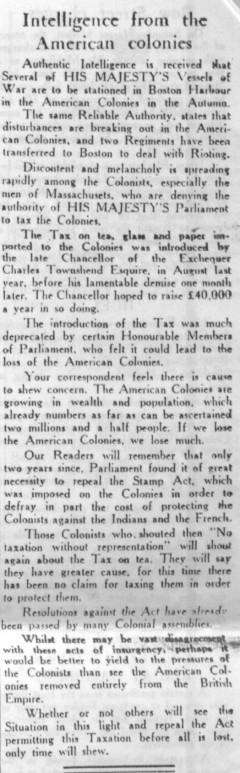

It happened that in 1766 the Government were looking for a man to command a ship for a cruise to the Pacific with the object of observing the transit of Venus. James Cook was the man for the post; he was given a ship, the Endeavour, of the serviceable Whitby collier type which he knew so well, and with a company of eighty-five set sail from Plymouth in August 1768, for the first of his three great voyages.

It happened that in 1766 the Government were looking for a man to command a ship for a cruise to the Pacific with the object of observing the transit of Venus. James Cook was the man for the post; he was given a ship, the Endeavour, of the serviceable Whitby collier type which he knew so well, and with a company of eighty-five set sail from Plymouth in August 1768, for the first of his three great voyages.

They rounded Cape Horn, and arrived at the lovely island of Otaheite, where they observed the transit of Venus - and the charms of the inhabitants. For three months they stayed there, on the friendliest terms; the king of the neighbouring island of Huaheine even insisted on exchanging names with the captain - and "Cookee" and "Oree" they became. Next they discovered and named the Society Islands, and then sailed for New Zealand, which was found to consist of two great islands admirably adapted for settlement "should this ever be thought an object worthy the attention of Englishmen." The soil was most fertile, the trees were splendid, the natives vigorous and healthy, though somewhat addicted to cannibalism. Domestic animals were lacking, and that Captain Cook determined to remedy at some future time.

Then they sailed for Australia - New Holland as it was called - explored the east coast for two thousand miles, and took over the country in the king's name. Narrowly escaping disaster when the ship ran on a coral reef, and "beat with great violence upon the rock", they made for Batavia, sailing between New Holland and New Guinea, thus proving them to be two distinct countries.

And now malarial fever and dysentery broke out: the whole ship's company were down with it at one time or another, and no less than a third of them died. They made their way home by way of the Cape and St. Helena, and dropped anchor in the Downs.

Cook spent but little time with his family, for in the following autumn he received another commission, "to complete the discovery of the Southern Hemisphere". He was given two ships, the Resolution and the Adventure, which he took great care to provision with proper food stores, including lemons, enough to last for two years. He left England in July 1772, and sailed by way of the Cape far south into the Antarctic Ocean. For weeks he sailed among icebergs, pushing south wherever he found an opening, while the ship rolled gunwale to, and the frozen rigging cut their hands. After a run of "three thousand five hundred leagues" they put into Dusky Bay, New Zealand, where they landed domestic animals and planted English vegetables. The next few weeks were spent among the islands, where old King Oree was overjoyed to see them; and then once more they sailed to the southern ice. At last in January they reached the great ice-field and could go no further. Cook sailed his ship right round the Pole, and the great southern continent of the old maps proved to be non-existent. He turned for home, discovering and naming many islands; and after crossing a greater space of sea than any ship had ever crossed before, returned once more to England. And this time, during the whole voyage, they lost but one man by disease.

In less than a year Captain Cook was again in command of the Resolution, but not before he had been promoted to the rank of post-captain, and had been presented with the gold medal of the Royal Society and a Fellowship. On this voyage he had with him as navigation officer a young man of twenty-three, of outstanding navigational ability and a sense of location amounting almost to "second sight". His name was Bligh, to be known the world over in years to come as Bligh of the Bounty. The object of this third voyage was to find out whether there existed a north-east passage from Pacific to Atlantic; and for this purpose he sailed to the Pacific, visiting Van Diemen's Land, New Zealand, Otaheite, and the Friendly Islands. Then course was set for North America. The Sandwich Islands were discovered in February, the mainland of America sighted in March 1778. All summer they explored the coast from Oregon northwards, through the Bering Strait, right up to Icy Cape, enduring storm and hardship and privation without complaint; but there was no sign of an ice-free north-east passage; and Captain Cook decided to return to Hawaii in the Sandwich Islands.

Then came the end. The natives were celebrating victory when they arrived, and mistook the Englishmen for their great god Lono and his immortal company. Divine honours were offered; and strangely enough Cook accepted them - perhaps because he was prepared to accept anything that made for the success of the expedition. Trouble soon began, when it became apparent that the entertainment of a god was an exceedingly expensive affair; while the death of one of the immortal crew, and his burial on the island, put a certain strain on even native credulity. Quarrels became frequent; sticks and stones were freely used; and Cook decided to sail away, much to everybody's relief.

Within a week the Resolution had sprung her foremast, and they were back again. Trouble began immediately. One of the cutters was stolen, and Captain Cook put ashore in some force to effect restitution. Natives crowded the beach, armed and excited. Stones were thrown and there was some firing. Cook turned, and as he did so was stabbed in the back and speared. He fell dead into the water.

Thus died Captain Cook at the age of fifty-one. His indomitable perseverance and courage, his disdain of comfort, his calmness and capacity in danger, and his singleness of purpose, have, with his stupendous achievements, marked him as one of the greatest of Englishmen.

Fortunately, we have very full and comprehensive accounts of all three voyages. The core and by far the most important part is, of course, the log or journal kept almost daily by Captain Cook himself - to which we must add the short conclusion added after Cook's death by Captain King. Cook's narrative is written on folio sized paper, for the most part in pencil, in a firm, clear hand without flourishes - as one would expect. And very wonderful it is to turn over the pages to some great occasion such as the end of May 1770, and read of the first landing at Botany Bay and the flying of the English flag, written up by Captain Cook the same evening on his return to the ship. Until recently it has not been possible to do this as the manuscript has been in the possession of the reigning sovereign. But a few months before his death King George VI presented the manuscript to the National Maritime Museum where it is now kept as a unique treasure - a locked book in a case within a safe.

Besides the basic account there is a great mass of material - biological, botanical, anthropological, and so forth, which in the full editions has been incorporated in the text with great skill. In addition, several attempts were made to edit copies of Cook's rough documents into the classical style favoured at that time. One such editor was Dr. Hawkesworth, who was given leave to "improve" as he thought fit, which he proceeded to do by copious additions, grandiloquent phraseology, and learned classical allusions - as may be read. Where Cook tells us that he walked about with the king of the island, Dr. Hawkesworth must say that "the commander pursued his journey under the auspices of the potentate". Where Cook records that they watched a native wrestling-match, Dr. Hawkesworth notes the resemblance to the athletic sports of remote antiquity, quoting Fénélon's Telemachus, and reminding us that Aelian and Apollonius Rhodius impute a certain practice to the ancient inhabitants of Colchis, a country near Pontus in Asia, now called Mingrelia.

Then came tragedy. For Captain Cook returning from his second voyage, and reading what he was supposed to have written, was shocked and outraged, and would have none of it. And poor Dr. Hawkesworth in bitter disappointment took ill and died of chagrin; and so never even had the pleasure of spending the £6,000 for which he had worked so earnestly and so deplorably.

After that the manuscripts were handed over to a Dr. Douglas, then Bishop of Carlisle, to deal with; and he assures the reader that not a word of Cook's original manuscript has been altered; and that, though there are certain omissions, is undoubtedly the case. Even so, Captain Cook thought it necessary to preface the Second Voyage with a sort of apology for his own supposed literary short-comings; and this is what he writes: "Now it may be necessary to say that as I am on the point of sailing on a third expedition, I leave this account of my last voyage in the hands of some friends, who are pleased to think that what I have here to relate is better given in my own words, than in the words by another person, especially as it is a work designed for information, and not merely for amusement; in which it is their opinion that candour and fidelity will counterbalance the want of ornament. I shall therefore desire the reader to excuse the inaccuracies of style, which doubtless he will frequently meet with in the following narrative; and that, when such occur, he will recollect that it is the production of a man who has not had the advantage of much school education, but who has been constantly at sea from his youth; and though, with the assistance of a few good friends, he has passed through all the stations belonging to a seaman, from an apprentice boy in the coal trade, to a post-captain in the Royal Navy, he has had no opportunity of cultivating letters. After this account of myself, the public must not expect from me the elegance of a fine writer, or the plausibility of a professional book-maker; but will, I hope, consider me as a plain man, zealously exerting himself in the service of his country, and determined to give the best account he is able of his proceedings".

Captain Cook writes modestly, but we now realize that a plain, sailor-like style is admirably suited to a narrative of endurance and achievement; while in descriptive passages, such as that of the great ice barrier, its very simplicity lends a vivid charm. Take, for instance, his description of the southern ice barrier:

"On the 30th, at four o'clock in the morning, we perceived the clouds over the horizon to the south to be of an unusual snow-white brightness, which we knew announced our approach to field ice. Soon after it was seen from the topmast-head, and at eight o'clock we were close to its edge. It extended east and west far beyond the reach of our sight. Ninety-seven ice hills were distinctly seen within the field, besides those on the outside - many of them very large, and looking like a ridge of mountains rising one above another till they were lost in the clouds; the outer or northern edge of this immense field was composed of loose or broken ice close packed together so that it was not possible for anything to enter it. This was about a mile broad, within which was solid ice in one continued compact body. It was rather low and flat (except the hills) but seemed to increase in height as you traced it to the south, in which direction it extended beyond our sight. Such mountains of ice as these, I think, were never seen in the Greenland seas, at least not that I ever heard or read of, so that we cannot draw a comparison between the ice here and there".

Letters and logs were consulted at the Admiralty - The whole work is thorough, accurate, and of reasonable length. The third voyage is partly told by Captain Cook, and doctored somewhat in the editing; partly by others, notably by Captain King, who continued the narrative from the point where Captain Cook's ended abruptly. The three accounts together form a fitting record of unmatched achievement.