Let me not linger upon this scene; the child was dead;

THE LEAFS

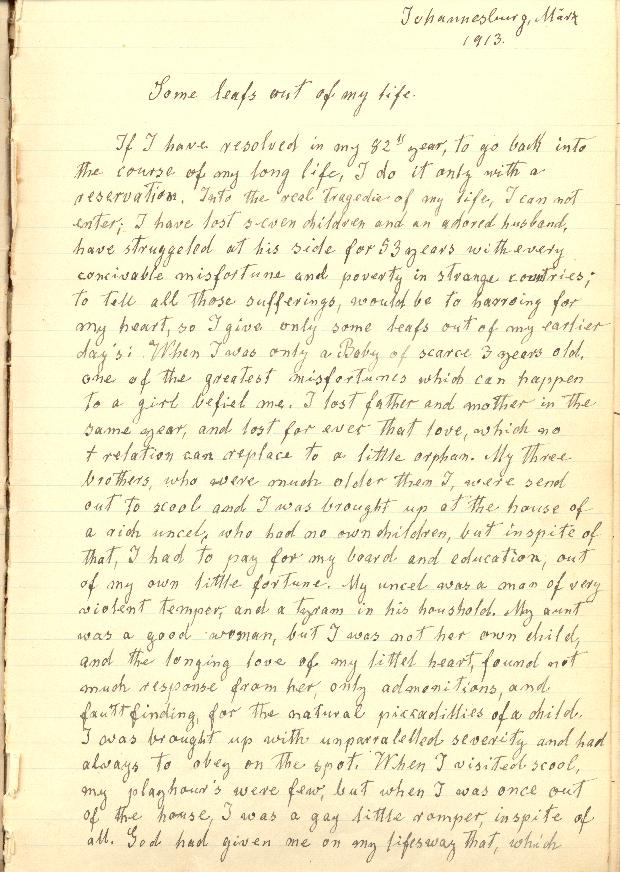

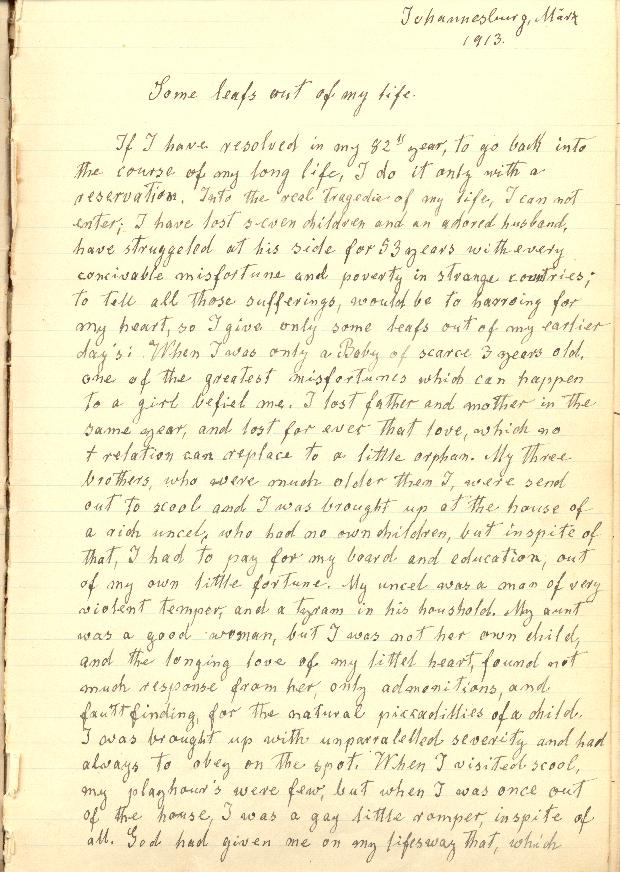

Johannesburg, Mar, 1913.

Some leafs out of my life.

If I have resolved in my 82nd year, to go back into the

course of my long life, I do it only with a reservation. Into the real

tragedie of my life, I can not enter; I have lost seven children and an

adored husband, have struggeled at his side for 53 years with every

concivable misfortune and poverty in strange countries; to tell all those

sufferings, would be to harroing for my heart, so I give only some leafs

out of my earlier day's;

When I was only a Baby of scarce 3 years old, one of the

greatest misfortunes which can happen to a girl befiel me. I lost father

and mother in the same year, and lost for ever that love, which no relation

can replace to a little orphan. My three brothers, who were much older than

I, were send out to scool and I was brought up at the house of a rich

uncel, who had no own children, but inspite of that, I had to pay for my

board and education, out of my own little fortune. My uncel was a man of

very violent temper, and a tyram in his houshold. My aunt was a good woman,

but I was not her own child, and the longing love of my littel heart, found

not much response from her, only admonitions, and faultfinding, for the

natural piccadillies of a child.

I was brought up with unparralelled severity and had always

to obey on the spot. When I visited scool, my playhour's were few, but when

I was once out of the house, I was a gay little romper, inspite of all. God

had given me on my lifesway that, which has been for ever afterwards, my

staff and help, a sunny and plyable temperament which always broke out

again through the dark clouds, which hovered over my childhood. My heart

can still bleed, if I remember, how unmercifully I was beaten, for the

smalest fault, so that our houskeeper, who was a nice, good girl, has

sometimes washed the blue streames on my shoulders, with tears in her eys. I remember once, when there was no proper cane in the house, I was send with the housemade to a shop, to bye a wip; I see it still before my eye's - it was a red & white leader knut, with 3 strong knot's on one end, and as I had to carry it home, I feelt always, as if all the peopel in the street,

must see, that it was destined for me. Half dead with fright and anguish, I

came home, and delivered the instrument for my punishment; but there must

have come a human feeling to my uncel, that the fright I had suffered was

punishment enough, and he let me go for that time. Our house was a large

on, and when evening arrived, I had to go alone 3 big starcaces, up, the

two latter ones quite dark, as no light was allowed me, to my bedroom on

the top of the house. It was a large room with a dormer window. Here I had

to undres in the utter dark, my head sometimes full of robbers & gost's,

here I sat many an afternoon, when my scoolwork was done, with my dolls,

sewing for them, here I lay often in my window, of an evening, looking at

the stars, and asking myself: on which of them, my dear mother was living,

and could she see her little girl, and know how lonely she was? -

My uncel was a conneseur of musik, though he, as a Doctor

with a large practice, had given up long ago, to play. But he insisted upon

my strictly to practice a full hour, when I came from scool. For some

year's, our piano, which my aunt did not use, stood in a large salon, were

it was in winter, bitterly cold, and was only heathed on the day, my

teacher came. All the other day's of the week, I had to practice in the

cold, with my little mantel hooked about my shoulders, but my fingers

feeling like ice. -

In this way, I came to my fourteenth year, and as I grow in

stature and good look's, I begann to find grace in my uncel's ey's, and I

was usefull to for him. He had very weak ey's, and reading fatigued them

greatly, so I had to come at seven o'clock in the morning, to sitt at his

writing tabel, and read medical brochures to him, while he was dressing. At

8 o'clock we breakfested, but I had often still late in the evening, to read the papers to him, which was very tiersome to me, while the medical papers interrested me, that in time, I often wished, I was a man, and could studie medicin.

I got now a teacher to cultivate my voice, I had a

beautifull and powerfull Alto and my Teacher wanted to educate me for the

Opera. But my uncel would not hear about it, and there was an other

obstacle to it, because my one ear had suffered in the Scarlatfieber, and I

could not hear so well as it is needfull for a singer on the stage. We had

two closed sit's in the royal teather, which then was considered the second

best in the whole Germany, and I visited it often, and heard with

enthusiasme most of the greatest Opera, and my love for music was fostered

in no small degree through it. The theater was almost my only plaesure in

life, though we visited the Casinoballs two or three times each winter; I

was not allowed to ascociate with any of my schoolfriend's only the

daughters of two families, where uncle was house-physition I was permitted

to see sometime, but after a few years he quarrelled with those people, and

from that day I was forbidden to have anything to do with them. Now the

uncel's behaviur to me, begann for me to be very pusseling and painefull. I

did not understand why he was so severe to me often, before my aunt, and

wanted to make it up in affection behind her back. I was all this time in

an uneasy and most unhappy state of mind, and it was like a tray from

heaven for me, as I was one day told, I was for one year to go from home

into pension to a Mrs v. Bissing, where a daughter of a friend, a sort of

second cousin was living just then too. Colonel v. Bifsing was poor, and

had only his pension to live on and his wife tried to better themself in

taking one or two young pesioners into the house. I close now as the first

part of my youth, as in going to Nienburg the course of my life begann to

go in a quite contrary direction.

~~~~~~~~~~~~

On a cold, but sunny morning in January I arrived on the

Stattion of Nienburg, which was on of the larger provincial town's of

Hannover. A military looking gentelman in civil and his very stout wife

accosted me directly between all the passengers, as if they had a

description of me, and brought me to their home. Here Mrs. v. Bifsing spoke

to me in such a warm and motherly way to me, that she wonn my heart

directly, besids, the presence of my young cousin, who greeted me joiusly,

made me feel soon at home. I was taken by and by to a round of visits and

made aqquaintance with some young girl's, on or two became afterwards very

dear friend's to me. Six of us arranged a readingclub, were we raid a book

together once a week, in the alternate homes of ours; and this free

intercours with young girl's, which I had always so wanted, did me

inexpressionately good. The whole life in Bifsings house, seemed to me so

patryarcaly, after the stiff splendour of my uncel's home, and the loving

care Mrs v. B. always showed to me, the more she knowed me, made me feel

very happy.

So three month's went by. Over us lived two old maid's, who

used to let two of their rooms out, and on day there came a young officir,

who joined the regiment new, and took them. Alexander Gropp became by and

by a general favorit between the Lady's of Nienburg, but I had very little

intercourse with him, because, and that was our only grudge against our

fostermother, she would not allow us to go to the Casinoball's, although we

had many proposals of married Lady's to shaperon us. All what concerned

young man, she watched over us with Argus eyes, but it did not help her.

Oneday, there came the Doctor of the Regiment, a personal friend, and

begged Mr v. B. to permitt one to visit, on the next evening, under his

wife's shaperonship, a ball which he gave in his house. My cousin Auguste,

who was only 16, did not count, but me, he would have, and he got me. It

was a splendid ball. I dansed three times with Lieutenant Gropp, we went home together and we fell in love together.

The old Bifsings lead only a very retired life; she was a

highly cultivated lady, an authoress, who had written a lot of book's,

which were all stapeld in a large glasscase in her room. The only social

way in which she moved, were lady's tea's or coffee's, so my young

Lieutenant had very little opportunity to meet me, but he contrieved to see

me on the stairs or when he knowed that Mrs B. was at her weekly Whyst

party; and after 6 month's, on one of this afternoon's, we engaged to each

other, of course in secrety only Auguste was our knowing friend. But on

unlucky evening, when the Colonel came home from his Club, he found an

officiers white glove on the tabel, and he pounced upon it, as a bird of

prey. Everything came out, I had a dreadfull scene with Mrs B. and my lover

had to leave the house, and was forbidden to see, or write to me. It was

only a few month's before my year with Bifsings was at an end, and as I had

written to my eldest brother in Vienna, that I was resolved not to go back

to my uncel's house, telling him my reasons, my youngest brother, whom I

best knowed and loved, came to Nienburg, and brought me to his comfortable

bachelor dwelling, to live with him. My uncle was of course very incensed

about this arrangement, and told me, I had gone "from the horse upon the

ass". For the next two years and a half, there came a time of prosecution

to me and my lover, which I better avoid, to enter into. But the long and

sad struggel ended, favored by circumstances, in our victory. The engl.

frensh war had begunn, and as it was a very bloody one, England was going

to form a german Legion. Many young officiers, tired of the long peace in

Germany, and no advancment, left the hannoverian armee, to enter this

Legion, and so did Gropp inspite of threathenings and promises of kinds.

For him, it was harder, this struggel against a father, whom he loved,

whose only son he was, and had been, till then, his pride. After his

commifion as premier Lieutenant, had arrived, he took me over to England,

then no minister would marry us in Hannover, as we were both minors. In

Germany the majority of peopel was then only reached with the 25th year.

He had made arrangments, that I lived for the fourthnight, before we could be married by licence, with a friend, a Captain Lacroix, who lived with his familie in the upperstage of a pretty Villa, in which we were to live afterwards just above them, an in which the lower flour, was occupied by our Major. They were all german, who had left the regular armee, to make more carriere in the German Legion. Here at Lacroix's, with whom I got intimately befriended, was afterward's, my wedding, and many young officiers attended it. At about 10 o'clock, in the still winternight, we heard suddenly under our windows the soft sound's of a silver trumpet, blowing the last rose of summer with the full accompanyiment of the regiments musik, who all assembeld to do us honnor. From that day on, we three families, each in it's own flatt, keept house together and had our dinners together, when our husbands had come from duty at the camp, which were lying high up on the Thorncliff. Here the regiment recieved sollemly it's collors, to which ceremony, the prince Consort Albert and the duke of Cambrige came expressly over. Afterwards there was in a big tent a breakfast, given by the General, to which we were asked to attend, and then prince Consort said publicly, that, if the Legion had served with honor

during the war, which he not doubted, and peace was restored, he promised

that the troupe should not be dissolved, but should remain in the regular

engl. service as a special life regiment of the Queen. 3 week's after this

the Regiment got orders to embark for Constantinopel, and we had to part

with a sore heart. I and Mrs Lacroix went to Göttingen, were her parents

lived, also a retired officier, and I found in Collonel Prizelius and his

wife, warm friend's, who did all to cheer me up, and console me through my

strawwidohood.

But this wiedowhood was in danger, to become one in ernest.

The old warchip, in which the 2nd Regiment was embarked, lost on it's

theard day in a storm, a scrow, and was from that moment ruderless. To make

the misfortion full, on of those dreaded and most dangerous fog, came down,

and the rudderless ship wavered about on the high sea, and nobody knewed,

were they were. In this calamity, the Captain told the officiers, that the

chip was in the greatest danger, and he quite helpless. He advised them

therefor, to write letters of farewell to those, who had loved ones at

home, and he would seal them down into a bottle, to trowe in the sea. So my

young husband of 3 week's, had to sitt down, and write an eternal farewell

to me. After this dreadfull night of terror and grief, the morning rose at

last, the fog was dispelled by the rais of the sun, and lo, and behold, to

their ashtonished eyes, they found themself on the Ride of Spithead.

Without their knowing, the ship was trown back, all the way, they had come

and in this way, a whole regiment of despairing men, was saved from a

watery grave. - -

I had promised my husband, to come after him to

Constantinopel, were they had to lay, till farther orders, and he wrote for

me directly they landed. I should travel with my friend Lacroix, but at the

last, she was persuaded to stay with her parents, as she had two children,

to care for, and this journey would cost a deal of money, which she had, to

consider. But I had just received my little fortune, and nothing was to

dear for me, to join my beloved, at least untill the day, when he had to go

to the Cramienfronct. So I travelled all the way alone and unprotected,

till the dragoman meet me, at my husband's order, on board of my ship, and

brought me to the big Camp, were my in husband's tent, we were at last,

united again.

As Tera, the christianpart of Constantinopel, was

overflowing with strangers, and no proper loging for me, was found, he had

taken a flat in Culalee, which lay on the asiatic side of the Bosporus; a

gloomy place with long dead empty street's of stonehouses, which were most

of them windowless, as the oriental fashion was more, to have the windows

courtward. But my room had windows, and when I looked next morning out, I

saw in the long gloomy street, a single turkish woman coming, who looked to

me, in her whithe bandaged an veiled head, and long black garment, like a

gost. Our hostess, a turkess, who wanted to show me some attention,

although she had nothing to do, with our board, shuffeled in the morning to

my bed, to bring me a turkish breakfast. It consisted of a eggshell of fine

porcelan, in a little silver filigranholder, with coalblack coffee without

sugar, and a macaron, of which the turks are very fond. As my husband had

of course to be most time at the Camp, which lay on a Cliff above Culalee,

I was much alone. Once when I was sitting at my window, I heard a tinkling

bell, which came nearer and nearer, and when I put my head out of the

window, I looked direct under me in the upturned face of a corpse, which we

openly bared, according to theyr custom, brought to the graveyard.

What consisted my houseceeping, I was of course, quite

helpless, but our white servant (a soldier) was a genius. I maid my

proposition for dinner, and he went to market, and cooked it, downstairs in

the kitchen; I had nothing to do, he made everything ready, and served it

with the greatest diligence, and we eat it quite satisfied; it was only

long afterward, when I found out, how hard it often became to get proper

provisions, that we had often eat, goat's, and dogsmeat. To my great joy,

we were moved after one month's stay in this dull place, to a little palace

of the Sultan, which he had offered for use of the europain lady's of

Officirs, and here I was in quite a different world. I am handycapped

writing in english; thoug I have my own language pretty well in my power, I

am unable to descripe the poetical beauty of the Bosporus, properly. I have

seen a pretty great part of the world, but never found a place, which could

be compared to it. The palace, we lived in, was built immitiately on the

shores of the Bosporus, so that, the baywindow were I sat, was directly

above the water. The Golden Horn and the Constantinopel with it's towers

and minarets, was opposit me, as lying on a tray. Many big warships, and

hunderd of Cayk's, sailed every day past me and by and by this little boats

came under my window, offering, real mountains of splendyd cherry's and

other fruit, for sale. The one side of the water, was lined with many

marbel palaces, but the other side rose softly hillward, like the Berea,

only that this hills were covered with almost black looking Cipresses,

through which shone the withe Villas and minarets. The latter ones had all

on the top a balustade all round, which were brilliantly ligthed at night,

and when allaround everything was black, this wreath's of shining light,

looked, as if they were hanging in the air all round this wonderfull Oval

of water. This were the Halciondays of my life, and their remembrance will

live with me, wile I breathe. - -

But alas, such day's, the more happy they are, the shorter

are they! One morning, after I had been 4 month's in Constantinopel, we

were awakened by the clang of hunderd's of bell's, and then came the news,

whiche was a thunderclap for the Legion; Napoleon III had suddenly made

peace, and our soldiers were to go back to England, without having once

drawn their swords.

~~~~~~~~~~~~

As no woman was allowed on a ship of war, I was obliged to

return alone to Germany back. Besides the uncertenty was our fate would now

be, under such circumstances, this journey turned out for me very

unpleasant. The elderly Lady of a superior Officier, a Mrs Swinfurt, was

traveling with me, so that I was not quite alone. My husband brought us one

morning on board of Steamer, which was to bring us to the source of the

Donau, where we had to embark on a different ship. When we sat on the deck

on this first morning, and said farewell to our wonderfull sourroundings

with a sad heart, I remarked opposit to us, a lady with a vixenish face,

and a very funny, old fashioned hat on. I could not help, making a smiling

remark about it to Mrs S. and the stranger must have gessed it, because,

from that moment she regarded me with daggerlike glances. I took no farther

notice, but went down to see to our beds. The womanpassengers had to sleep

all in a large Salon, where around the wall's were always two cott's above

each other; the upper one was only to be reatchet through a little ladder.

The Steward showed us two beds, of which I of course chosed the lower one.

Shortly before retiring for the night, a young englishman came to me, and

told me in broken german, that I had to give up my bed, as his wife had

claimed it, before me. The wife turned out, to be, that spitefull looking

person on the deck, and a would not beginn to quarrel with her personaly,

and as there was no other lower bed was emty, I had to make up my mind, to

clime the littel ladder, and laid down in the upper cot. They were all so

fastened to the shipwall, that there was a little space between, and in

that stud in every bed a smal wooden bowel for the sick. Soon after we had

all gone to bed, the sea begann to be very rough, and I became very ill. I

had used my bowel severel times, when suddenly the ship gave a voilent

lurge to on side, and lo, my bowel slippet down into the lower bed with

it's contents. I heard a scream under me - at the same moment I got ill, and as my bowel was gone, I turned to the outside of my cot, and delivered my Tribut to God Neptun, upon the devoted head of my antagonist, who were just that moment crawling out of her bed. For the second time she yelled out and fleed out of the Salon. I was realy to sick, to feel sorry for her, and I never saw her again. As I heart afterwards, she had insisted to sleep

at the hospital. The second part of this voiage had it's sufferings too.

Again the Lady's had to sleep in one Salon. It was fearfully hot wheather,

and the Salon was suffocating. One day it overcame and I feel down in a

deep swoon. As I heard afterwards, they all crouded about me, till suddenly

the Captain came down, took me in his arms and carried me on deck. Here I

was given a little lofty pavillon, were two bed's for me and my compagnion,

were made up, and in that way, intierly through the kindness of the

Captain, I ended this voyage in comfort to Triest. In Vienna, where I had a

married cousin and my eldest brother, I rested some week's, and then went

back to Göttingen, where my old friend's, the Prizelius, had taken a nice

lodging for me. Here, after some times, my husband came for some week's on

leave, when my first child was boren. But he brought me, the wellcome news,

that the english goverment would form a new troupe for the Cap of g. Hope,

from the Legion, and that all the married officiers were to be send. It was

just after the big Zuluwar, and this new troupe should be destributed all

around brittish Caffraria, as a protection against new invasions.

~~~~~~~~~~~~

My husband's leave was up, and he had to return to England,

but when my little daughter was five weeks old, I followed him and a white

servant. But we stayed only about two month's in England, when we embarked

to black Africa. The goverment had promised to keep us for seven years in

pay, but nobody of us, thought to stay there after that time. We all

thought, by that time, we would be quite rich, and would return

triumphantly to our fatherland. Alas, how good it is for our mortal mind's,

that the future is always a dark riddel for us! who would have courage to

enter on on's way of life, if on could see all the misery's which was

waiting for us! Well, but we went from England with a light heart on a

sailing vessel, and after fully 3 month's at sea, on morning our delighted

eyes saw for the first time, the grandeur of the Tabelmountain, and the

beautifull haven. By and by we came to East London, which then was only a

smal dorp, with a dozend houses, and were from there expedited per

Moolwagons through the country. All along on the way to Kingwilliamstown we

saw field's, white, strewed with bleached bones of man and cattles, were

the wandering hard's of the Zulus, had killed their old men and oxen, to

devastaid the country for the folloing soldiers. After a pleasant time at

the comfortabel barrack's in King W. town, we were destributed through the

country, were each Compagnie with some officiers, were to establish a

village, and each officier had to receive an amount of goverment land for a

farm. We were in so fare lookign, that our place, called Breidbach, was

only about two hours from the town, so my husband rod often out, to

supperintend the building of a water & tap house, and some Cafferhud's,

were we must lieve, untill a stonehouse could be build. We had no other

workmen, as the soldiers from our village, and they had constructed our

future dwelling of two large rooms, with a tremendous thatchroof over it.

It must have cost cartloads of straw, but we thought only, how beautifull

cool it must be, through the hot summertime. Our hut lay on a little hill,

and at the foot of it was our garden along the Yellowriver. It was, so near

the water, very fertil ground, and we planted joifully all sort's of

vegetabel, planted tree's, laid out asparragood field's, e.c.t. and in the

evening we sat hand in hand before our little house, and looked admiring at

the stare of the South, which was every evening just before us.

We were quite happy; but still, the little plagues of life,

begann already to show themselfs. We had, about an hour from us, an evil

neighbourhood, in a large Cafferdorp. It's chief, Cetwayo, came before

long, to make acquaintance with us. Now I had in Kingwilliamstown often

admired the magnificent Caffers & Zulus who worked for Goverment, their

figures and the inimitiabel grace in which they stepped about in their

blanket and assagay. No roman emperor could handel his toga with more

dingnity. But, as soon, as they want to ape the Europaines, thei become

loudicrous. So this chief rod on day before our door, on a thin old

Clepper, his bridle was an old red cotton hankershief, his dress, an

abdicated Officiers crimson undress jacket, only he had mistaken the front,

and it was buttoned all along his back. The whole crouned and old, battered

chimneypot. He came, to assure us of his goodwill and if we wanted to buy

anything, cattel, foods, e.c.t. we could get it cheap at his craal. So my

husband bought several cattel there, but we found to our sorrow, that all

of them and more, found in a strange way, their old home again; no week

almost passed, that not some thing was missing, and no inquirings or

complaines were of any use. The cattel was driven misteriously away, and

the Chief was the personified innocense. One of the Cafferhut's was my

pantry, where I had stowed the nice china, which I had brought with me from

England, and it broke nearly my heart, when so often at dawn, I was

awakened by the clattering of my breaking china and the screaming of my

fowls; but when we rushed out, there was nothing to be seen as the broken

cups and saucers, so dear to my heart, and the mifsing of some fowls or

ducks. But we had other trouble! The ground of our farm was of course

virginsoil and almost as hard as rock. When a german peasant has one or two

horses before his plough, we had ten oxen and two caffers with chamboxes,

and when with He an Hallow and much wipping the poor beast's had been

working a whole day, there was in the evening not more ground done, then

this house covers, and what growed upon it, was half weeds. Of cours, the

yong officiers, who had no idea of farming, made often great mistakes, and

so did my husband, although not so great ones, as Lieutenant Ritter, who

complained once bitterly to us, that he had sowed a whole bag of

splittpeas, and nothing had come out of it. Our real housebuilding was very slowly going on, those ones of the soldiers, who were masons, my husband

had engaged, each of them getting 10 shilling a day, and they tried their

best of making hay so long the sun was shining, and were so lazy as

possible. My husband had about this time often to go for whole days to

Berlin, to sit in jugement over the many cases of desergion, which now

occured in the troupe, and so our masons were without supervision, and

could wast the time away, but came very faithfully for their 10/- every

night.

Now begann the rain time, and during the 30 years I have lived in this country, I never saw such flood of continual rains, as we had then. As we had in our little abod only tramped mutt floors, the dampness of the whole place was growing more and more, till it brought on, the intermittent fieber to me. The Doctor warned me, but I was obliged to stay, and so the misfortune happened to me, that one evening my Baby was born two month's before his time. Nobody, in those hard hour's was round me, as two young woman from our village, who had no experience themself. Well, inspite of everything my child lived, but no nurse from town could be induced to come in that dreadfull waether out to a lonely farm. So I had to do with those woman of the village, who went in and out of our house, at their sweet will. The rain had succeded to ruin our tremendous thatchroof, it begann slowly to sink over our heads, so that big props had to be put up and I had to lay with an umbrella in my bed. Fortunately my husband found a young cafferwoman as wetnurse for my child, but I got the milkfieber, and they had to cover me up, and carry me over in my bed, to on of our

Cafferhut's, because our roof became to dangerous. Here I became very ill

and had to sitt for six month's with a sore breast. When I was able to get

up, and live again under our mended roof, I bestirred myself to found out,

what had become of my household and property, during my long illness, and I

made woefull experiences. The whole village seem to be, a veritable nest of

thief's. When I dragged myself through the house, still weak and miserable

from my long illness, the pride of my youth, my biautifull long hair, all

cutt of, I wept miserable tears when I beheld the devastation of all I had

owned. My juellery was all gone, because we had no furniture, were we could

lock anything away. The mise had made a hole in the large box, were I kept

the beautifull dresses of my trusseau, and what the dampness had not done,

the mise had destroyed, as I found almost in every dress big holes eaten

in. It was quite a knockup for me, to see all this. It seemed, that the

whole village had preyed on us. The carpenter who had made the woodwork of

a little divan for us, which I would cover myself, came, when he brought

it, in one of the fine linen shirt's of my husband, on which I had sown the

front's of myself, in the then fashion of fine quilts, and the divan was

covered instett of corse linen, with one of my own tablecovers. Tackled

with all this, the carpenter asserted that he bought the things from a

soldier, who had afterwards deserted. There was nothing for us, as to bear

it and keep still. The Capgoverment, who had promised to keep us for 7

years; after two year, when they saw, that the Zulu's were quit subdued,

and the country safe, thought better of it, and put us upon half pay and

after 18 month's more, discarded us althogether, as of no more use to them.

From that time on, everything went down with us, though I had made us of my

musical talents, and wrote twice every week to the town, and gave lefsons

in musik and singing. An advocat there offered to lent our farm and we went

out of the place, which had, in spite of all, become dear to us, and went

to Port Elizabeth.

We had to Oxenwagons, and my husband intended to become

transportrider with them. I got a very good recommandation as a

musikteacher to a wealthy familie there, and succeeded quikly in getting

some pupils. As to our oxenwagons, there hangs an other tale. My dear

husband had an inextinguishable believe in the goodness of men, and so, of

course, he was cheated right and left. He was born and breed a soldier, and

had not a vein of bussiness in him. I have in after life often heard an

read, that no man had more difficulty in finding a civil position, than an

army officer a.d. In waiting for proper load's for his wagons, he got an

offer of a dutch transport rider, who had more load's as he could take, to

lent the wagons from him. He inquired about this man, and heard, that he

often came there for wagonloads, so my husband lent him the wagons with 24

oxen, and he never saw man or wagons again. The farm in the Freestatets,

which he had told us, he possessed, turned out to be only a stonecraal for

his oxen, when he passed, but he was sly enough, not to pass there any

more. For some years I was abel to support my familie with given lefsons in

musik, singing, german, e.t. while my husband got a little place at the

court, through the juge in whose familie I teached, but it was told him

directly it was only for the time, till they send a goverment candidat down

there, which they did only all to soon. About that time I lost 5 of my best

paying young Ladies, who either married or went to other places, to live

and somebody advised us to go to Utenhagen, a town, only some hours from

Port Elizabeth. So we moved there with our two little girls, my other

Baby's all had died. Though we lived cheaper there as in the larger town,

and I got pupils, still it was not enough as the place was only smal. My

husband tried to open a scool for boys, but there was the Goverment scool,

which was so much cheaper, and he got only a few boy's.

So the year 1860 had come, and my husband, had sometimes

remarked, as a last resort, to his going to Amerika and serve there in the

armee during the bloody war, which raged between the northern - and

southern States, but I would not hear about it. But as time passed, and not

the slytest prospect appeared, of his ever to get employment in this littel

town, we had in the end to resign ourself to the thought of parting for a

time. Shortly afterward he saw in Port Eliza a Captain of a smal sailing

vessel, who offered to him, to take him over to New York for £5. only as a

companion. So we scraped all money together, which we had, and parted, God

know's, with what a sore heart, for a quite dark and unsafe future. How

lonely and abandoned in the whole world, I felt, no words can describe.

There I sat with three children, my baby boy was only a few weeks old, and

my whole stock of money being 11/6. I had not sleept the night, and was

sitting the folloing morning dressing my baby, and washing it with my

tears, when God send me a friend in the darkest hour of my life! An old

man, a merchant in the town, a Mr. Hitzeroth, who's daughter and niece, I

teached, came to me, and spoke to me like a father. "I shall do every thing

to befriend you in your sore need, I have a little house, quite close to my

own dwelling; you pack up your things, and to morrow morning I shall come

with servants and fetch you to your new home." And this good old man, his

wife and familie, have all the time, that I lived in their little house,

been my constant and faithfull friend's, for which I can never feel

gratefull enough. Alas, they all, except the daughter, are long ago in

their graves, but never will the love and estime for this good peopel, die

in my heart. They had made the house comfortable with nice furnitur

througout, because I had only very littel myself, and there was not a day

in all that long time, they did not send help to me in every possibel way.

When I was free of my lefsons, I was always in their house; the girl's

hanging with great love on me, and the old ones traiting me like a

daughter. I found some other nice people, who befriended me, gave me work

to do, so that in a short time, I could look quitly into the future, what

concerned my and my childrens livelyhood. But the eternal anxiety about my

husband's life, left me little peace. He wrote to me long letters on board

ship, in which he made himself the bitterest reprotches, of having left me,

and felt dreadfull unhappy; but I knowed only to well, that there was

nothing left else for him to do, as to dare the hard stepp, he had taken.

I have forgotten to mention, that after a few month's, the

man who lent our farm, had offered to buy it for £300. To us that amount

would be a fortune then, and my husband could invest it profitable. So he

consented to the proposal. When we left K.W.Town, he had given his power of

attorney to an agent there, for receiving the rent's; but month after month

went by, and the money for the sale, did not come, nor any ansver of our

letter. Then my husband went himself to K.W.Town, saw the advocat, and

heart to his ashtonishment, that he had paid the £300 long ago to the

agent, but that this man had shortly afterwards vanished, and sheated some

more people of the place. In this way, we got for our farm, with the

buildings theron, and all what we planted and worked, not a single penny. I

mention this only, to show, how absolut helpless my poor husband was.

In the time I speak of, there we had not got the regular

weekly mail, as now, only once in a month came the english post, and after

my husband had joined the armee, I had often to wait 3 month's, before I

could hear from him. During all that time, I never knowed, if he was alive,

or dead. Without the daily intimat and loving intercours of the Hitzeroth

familie, I do not know, how I would have endoured this dreadfull time. My

husband was twice wounded, and had born many hardships; they were often

night and day on the marshe, in the bitterest cold, so that, when they had

to pass through a pool, or littel river, the water on their body's was

frozen to eise in five minut's, and many a day, they had nothing to eat as

dry bisquets; but my husband said, he never felt better in his life. He was

with body and soule a soldier, and had found nice comrads, although he had

often to laughing an wonder, at the utter militairy ignorance of the

american officiers. In the beginning, the goverment had made men officiers,

who had hardly any education, but they had need of men, and took what they

could get. If my husband had joined then, he could by that time, be a

general, but this was the year 1864, and the war raged 3 years. After my

husband second wounding, he and an other young comrad were send to

Washington hospital, as convalescent's, and as they felt after a time,

strong enough to humpel about, they went together one evening to the Opera.

As they appeared in a loge at the first rang, they we greeted with an

undreamed of ovation. The whole publicum got on their feet, fronted the

loge, and cheered them, while the orchester sounded the american hymne. So

great at that time was the enthusiasm of the amerikan's for their warriors;

but alas, that enthusiasmus died very quickly, as soon as peace was

proclaimed. As the armee had almost always been at the move, the pay had

seldom come to them, my husband could never send me any money, but after a

time I could write, that I earned enough for my living. Directly after

peace the irregular armee was dissolved, and their was a multitude of young

men in Newyork, who were looking out for billets.

About this time, I got news from Hannover, that my uncel

had died suddenly, (my aunt having died some years before) and that he left

me a paltry thousend Thaler, after he had formerly told me, he would leave

me a nice fortune. My husband had written to me, if I could lent the money

in Utenhagen for the voiage, I should come to him, and should ask for him

in a certain Hôtel in Braodway. Now it happened, that there was just then

in Port Elizabeth a littel germain sailing ship; the "Juno" would leave for

Newyork in a fourthnight, and thanks to the prospect of my littel

inheritance, I was abel to lent the amount of our passage money. So I wrote

post hast to my husband, that I should embark in two weeks, and send the

letter, as I always did, to the german Consul in Newyork, because my

husband had not jet a fixed adress. So I said to my dear, good friend's,

farwel and went, loaded with presents and good wishes, with my shildren to

town, were I had one day to spend in a boarding house, to meet the Captain

of the Juno. That day broke out a fearfull storm, and the Captain told me,

he could not leave the port. He advised me to stay at the Hôtel, till the

weather brightened, but I, fearing the expense insisted on our going on

board; I did so, to my unduing! The Capt. promised, to send a joung man, to

bring us to the breakwater, where a boate should wait for us. It was

dreadfull weather, and was raining hard, when we left town, to walk fare

out to the breakwater, which was not then quit finished, only to planks

broad, and without a railing. The young man had my two littel girl's on his

hand's, my littel boy was sitting upon the back of a cafferwoman, and I

struggeled after them, hardly abel to hold my umbrella. The wind, which

were just coming right against me, beating my scirt's against me, so that I

feelt more then once, the portmoney with the £12. that I had saved from my

earning's, beat hard against my knee. On the whole way, we meet not a soul,

only once about a partie of a dozend Caffers. Quit out of breath, and wett

through we arrived at last at the breakwater and rested for a moment on a

dry place, when suddenly my bunsh of keys feal to my feet. Shocked I fealt

in my old dresspocket, and found nothing there, as a big hole, all I possessed of worth I had put in this pocket, which was quite whole, but the wind had so belabored my scirts on the road, that the heavy silver

portmoney and it's contents, had broken through. In my despair, I ran alone

all the way back to the Hôtel, in the vain hope, that I had left anything

in my room there, but there was nothing. I went back to the breakwater,

with the heartbroken feeling, that I had to travel to an other Continent

quite pennyless. The breakwater was a dangerous way for us! I am not free

from dizziness, and my head trobbed fearfully with the excytment; the

plank's were slippery from the rain, no hand railings for support, and the

great props, which healt the planks, trembling often, from the beating

waives. The man with the children were before me, as I suddenly fealt my

head swimming, and I would surely fallen over, when an old sailor, who was

whitout my knowing, just behind me, had not catched hold of me. So we were,

almost through a wonder, safe on board. The Capt. came only on the folloing

morning, and he was so sorry for me, that he went to town again, and

applied to a there existing Compagnie for misfortunes to travelers, for

help, and they send me a fife poundnote, which was a Godsend to me!

But this was the only thing, I had to thank the Capt of; in

other ways he was no blesfing to his passengers. He was a part owner to the

ship and had provided everything in the most stingie way. When we were

under the Aequator, we had no more water, a each, as one tumbler full, a

day, because the watersupplie was to smal, and when we came to a northern

hemisphaer, and begann to become cold, we never had a fire in the Salon. It

was January when we neared Amerika after more than two month's on board,

with very bad food. The weather was icycold, so that I had to sit in my

wintercloak the whole day in the Salon, and covering my poor, trembling

children, with it, like a hen, covering her chickens with her wings. I was

so impacient, to leave the abominable ship, that I would not wait, till a

tender came to us, the next day, but hired a littel boat, to bring us on

shore. It was so cold, that the spray, which feal on the leadercover of the

boat, was in two minutes, frozen to icecykles, and my two youngest creamed,

when they saw for the first time in their life, snow falling from the scye.

But I bore everything with a joifull heart, and looked only foreward to be,

all misfortunes baar, united to my dear husband. God had protected us both

trough many dangers and suffering; and as we had now through my littel

inheritance some funds, to beginn a new life, my first steps on american

soile, was with a light heart.

But that should only last for the shortest time! When we

arrived at the mentioned Hôtel, I heard, to my shock, that my husband did

not live there anymore and they could not tell me his adress. I went now to

the german Consul, who took always care of our letters. The man was very

friendly, but told me, he was himself astonishd, that my husband had since

three weeks not come to him, for his letters, as he always used to do,

since he was again in town. "Here is still a letter for him, which came

lately", said the Consul, and gave me the very letter, in which I told my

husband about our coming. I stood thunderstruck, and did not know what to

do. The Consul advised me, to go to a littel german Hôtel, where, he

knowed, many german officiers, used to go, and I would perhaps find a

chance, to see, one of his former comrads. So for the second time, I packed

my poor freezing children in a Cap, and drove to this Hotel. Here, I

resolved, to stay, and wait. After some anxious hours, came a Major Dodd

to me, and told me that my husband lived in the familie of a Mr. v. Uslar,

with whom he was in a sort of partnership as a broker. The Major offered to

go and fetch him, but after an other hour of waiting, came back, with the

news, that my husband went eight days ago, to Hobocken, to see some

friends, and had not returned.

The folloing day, the Major at last found him, in the house

of his friends, where he was just for the first time out of bed, as he had

a bad inflammation of the eyes, for the whole week. He was thunderstruck,

when he heard, that his wife and children were in town, as he could have no

idea, whitout my letter, that I had such a quick opportunity for my voyage.

I need not speak about our happiness, to be united again after the sore

trial's, we had undergone, and my husband was full hope, that in America,

he would better succeed as in Africa. But alas! here again came my husbands

trusting soule to the fore. He had no idea of the sharp business instinct

of the americans, of which he himself had not a vein; he had been persuaded

to give a large sum in an interprice in furs. A trader, who he was told,

went every year to the north for furs, and whom his friend knowed, as an

honest man, would buy for him, and he could realise a large profit. The

trader took the money, and that was the last, he saw of him. Mr. v. Uslar,

who had promised, to take him as a partner in his broker business, for a

good round sum, keept his word, after he got the money, and for month's, my

husband ran about town, and tried to sell to other firms, the articels,

which Uslar had for sale. But he came at last to the conviction, that

Uslar's business was so smal, that the earnings were hardly sufficient for one familie, and that the man, had only wanted, to get a good round sum

into his hand's. It was a hard, absolut selfish world, into which we had

entered, and no true friend, who took him by the hand, and advise him, not

to trust a single being in America, whom he did not entierly know, as an

honest man.

So there lay no blessing upon my littel inheritance, and it

was soon all gone. But my husband succeeded in getting a good place in a

large destillery; he got a hunderd dollars a month, from which we could

comfortable lieve. We bought now furniture, and setteld down in a nice flat

on sixt avenue.

I must now explain a matter about the destilleries of

Newyork. In that time existed a foolish law, that enforced a duty of two

dollars upon each gallon of wysky, wile the market price was less then

that. In this way the masters were obliged to make matters go with the

Goverment Inspectors, who got large fees to let things pass. As in America

was the law, that all officials had their place only for four years, this

people of course, wanted to make hay, wile the sun was shining; there was

no Goverment inspector who was not purchasable, and they were like the

wolves after the distilleries of the district, for their prey. Under such

miserable rules, it was of course not possible for any man, to keep a

distillery for any lenght of time; they frexently changed hands, and in

this way, my husband got the business from his former master, because he

could no longer stand the imputations of the inspector. My husband took the

distill reluctendly on account of the great backdrawings, with which it was

bound, but he did not know, what to do else, and if he could waether it

only for a year, he would have made money enough, to leave it. The manager

over the distillworks was a german and he persuaded my husband to give his

old father a good Salary and let him sleep at the works as a watchman, to

prevent thieving at night. Nevertheless it was found out after some

month's, that one night were rolled out of the backdoor, tons of Whysky,

wile the old man slept quitly in his bed.

About this time, my youngest little boy was born, and we

engaged a white wettnurse for him. Only a few day's afterwards, all my

children got the measels, and sick and weak, as I was, I had to walk about

between three sickbeds. My husband had some month's before, taken the

Inspector as a partner, as the man promised, he could keep other ones in

check; but my husband complained bitterly, that nevertheless, an other

inspector had begunn to make himself obnoxious with threaths, if he did not

get a certain monthly pay, and we were in great sorrow about it. From now

came blow upon blow on us unhappy people. My children were hardly

recovered, when my husband got the measels, and in such a violent degree,

that he was quite dangerously ill, and lay in bed more then 6 weeks.

Everything in the business had to go through only the hand's of his

partner, who in the whole time cam only once to my husbands bed to have a

power of attorney signed for him. As after two month's time, my poor

husband went for the first time to the business again, he found, that his

partner had not shown himself since a week, and after an anxious time of

researshes, he found out, that this man had cashed in every outstanding

debt's, laid his hand upon every dollar he could get, and vanished. My

husband made inquiries at Goverment about him, and they told him, that his

term of office had expired, and he had left.

But all this misfortune was nothing to the tragedie which

was to happen. The girl Julie, who nursed my baby, was in every way a

splendid nurse to him. She had lost her own child and loved my baby as if

it was her own; she was very proud of it, because it was indeed a beautiful

child. Julie was irish, and I had often heard, that the girls there, were

given easely to drink. But I had never remarked the slightest sign of such

a failing in this girl, though we found on evening, after we came late from

the Opera, that my husband wiskey bottle was tampered with, and water put

into it. But we had an irish cook too, and could not know, who of them had

done it, and after a time, I quite forgott all about it. Now it happened

that I lay in bed with a bad cold; the weather was winterly, but bright,

when Julie came to me, asking leave to go to a shop, to buy a dress, and

take the Baby for a walk. I let her go, only ordered her strictly to be

home half past four, because the sun set early and after that, it would be

to cold for the Baby. But 5 and 6 o'clock struck, and she had not returned.

By the time my husband came from the office, I was in a fiever of fright;

but what could we do, were could we seek for them, in the immense town of

Newyork! So we sat despairingly on and waited; it was 10 o'clock, when the

cook opened the door and beckoned to my husband; after a few minutes he

came back to me, put the Baby into my arms, and said, that the nurse were

in the kitchen, dead drunk. Let me not linger upon this scene; the child was dead; in the packed tramcar, she, in her drunkeness, had stiffeled it under her swhal, as the Doctor found out the following day. There was a jury, and I heard in my bed the tramp of the twelf man, and I felt as if

every foot trod upon my heart. -

Everything came over us in this dreadfull time. My husband

struggeled on for some time, but it was not possible to hold the distillery

longer after all the losses, and the greedines of the new inspectors, we

had to give up the business. From the still outstanding debt's, it were

about 11000 Dollars, my husband got nothing. There were sharpers, who had

one day a business, and got credit but did not pay. The way with the law

was very dedious and slow; but when we got at last a jugment, the business

was in other hand's, or some other devillerie was transacted, and we got

not a Dollar. The misfortune was, that my husband was not at all a

businessman and that he had been to free to give Credit.

As we had lost everything in Amerika, my eldest brother in

Vienna persuaded us, to return to Hannover, and he would give me a monthly

spipend untill my husband found some billet. But when we came to the town

were we both had grown up, it was not much better then a desert to us. The

year 1866 had passed, the town was now prussian, all old comerades gone, my

father in law, uncel an aunt, and my truest friend, my youngest brother -

all were dead. It was not more our fatherland, and the few persons of our

familie we found still, showed themselfs anxious for the poor relations,

and nobody could, or would reache out a helping hand. The goverment some

years work for my husband as a surveyor, and that was our best years in

Germany. When that work was finished, there was nothing more to do for him.

So it came then in the end, that we found ourself again back in old South

Africa, under the roof of the only child, who heaven had left to us, and

here I will close the story of my life.

It is not without heartace that I have written this leaves,

as all the bitter and sad grieves, were stirred up in me; but I went

through it in the hope, that the reading of my sufferings in the world,

will give to my grandchildren, a double feeling, of their own happiness,

and safeness in life with a good mother and good husbands. May my blesfing

be ever over all my dears, that is the best wish of your

Grandmother.

FOOTNOTES

by

Brian M. Randles

(Historian, Kaffrarian Museum, King William's Town)

Brian M. RANDLES (Historian, Kaffrarian Museum, King William’s Town, South Africa) published a transcript of these same memoirs in the "Coelacanth" (the journal of the Border Historical Society) in Oct 1981. In this article he also provided some footnotes which explain the meaning and context of some of the phrases used by Granny GROPP in her letter.

- "engl. French war". France and England declared war against Russia in 1854. (Crimean War).

- Captain La Croix, who fought with the Holstein Bundesknotingent between 1848 and 1851, entered the legion in 1855 with the rank of captain. He accepted the British offer of emigration to the Cape, where he died in 1857. (From "Mercenaries for the Crimea" by C.C.Bayley, 1977). He commanded a detachment of 100 men stationed at Cambridge. ("Germans in Kaffraria 1858-1958" by J.F.Schwãr & B.E.Pape).

- "Ride of Spithead". Spithead, roadstead, between Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight, England: Used by ships of the Royal Navy. (Where ships rode at anchor).

- "Cyak"="Caique"=a Turkish skiff or light boat.

- "Zuluwar". As will be seen again further on Mrs Gropp tends to confuse the Zulus with the Xhosas, even the names of the chiefs.

- "Moolwagens". The military preferred mules to oxen as draught animals. In the 1850's the Mule Train Establishment was built in King William's Town to accommodate mule-drivers, mules and fodder. After the Cattle Killing of 1857 which had been preceded by an outbreak of lung sickness in cattle, oxen would, in any case have been in short supply. (Mr G.S.Hofmeyer in litt. 6/5/1980 and verbal communication).

- "... had killed their old men and oxen". The Xhosas destroyed their cattle and crops in 1857 at the behest of the prophetess Nonquase and her associates, who had promised full grain pits and fine cattle in their place. There was no scorched earth policy ahead of the arrival of the Legion.

- Breidbach is 7km east of King William's Town - about 1 hour's walk.

- Yellowriver=Yellowwood River.

- The original agreement was for the legionaries to serve as military settlers from the date of their landing in South Africa and for 7 years after reaching their locations. Many went to fight in the Indian Mutiny and did not return. Many who returned were discharged and allowed to scatter over the colony and other parts of South Africa. Before this members of the legion had been allowed to leave their villages in search of work. In February 1861 the then remaining legionaries were paid off as of the 31st March 1861. The Legion had come to and end. . ("Germans in Kaffraria 1858-1958" by J.F.Schwãr & B.E.Pape).

- The American Civil War broke out in 1861 and ended in 1865.

- 1866-The North German Confederation was founded under Prussia.

all original material (text, graphics, photographs and/or programming) © 1998-2001

Sally Smith

http://geocities.datacellar.net/africamuse