APPROPRIATING PASCAL

SUBLIME POTENTIAL (A SERIAL ESSAY): PATH 1 - Sublime Potential / >Appropriating Pascal / Prolegomena / Schiller: Notes on the Sublime; PATH 2 - Linguistic Dust / The Coming Coming / Sublime Aesthetics / Sublime Scare Tactics / Red, Green, Blue

In 1674 the first French translation of Longinus' treatise appeared, penned by Nicolas Boileau-Despreaux. Boileau, according to Louis Marin, developed a slightly different reading of this text, than his predecessors; a reading that presented the effects of hypsos (the Sublime) -- and, please note, only the effects of the Sublime may be experienced, not the thing itself -- as "what delights, enraptures, ravishes, what strikes, seizes, surprises, bewitches, excites". This energetic reading was offered in contrast or as a supplement to similar, if not less sensational traits enumerated by Lefevre Tanneguy, author of a Latin translation, published in 1663, equating the Sublime with "grandeur, magnificence, dignity, weight, [and] intensity". The former, more scandalous terminologies seem to be aimed at a different part of the subject than the latter, in that the subject is the entire point of sublime rhetoric and is to be "weakened" and "dispossessed" by contact with this extreme force in language and nature. Let us guess that Boileau was aiming his pencil at the entire edifice of neo-classical figuration, architecture included.

It is not grandiloquence that matters in sublime rhetoric but petitesse énergique (energetic smallness). The experience of "rapture, transport, ecstasy, stupefaction, astonishment, or bedazzlement" (Boileau) brings the subject to the "threshold of indefinition"; and this is the point where Marin makes a bedazzling leap of his own by suggesting that the Sublime is 'where' the form encounters the limit that makes it a beautiful form. By most definitions (including Heidegger's), and pace Marin, the Sublime is an excess of beauty, a surplus, that resides outside of all forms (and formulations). This is useful to remember (and politely explain) when the Sublime is invoked to describe a mountain range, a woman or a work of art. The Sublime, in fact, does not ever appear and only shines within something else, a distant far off 'other' that can never be contained in linguistic or physical form. It is said that music may be the only artform that is truly sublime in itself. This, too, is why Poussin's paintings, which Marin has written at length about, especially in Sublime Poussin (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1995), are not sublime in themselves but are illuminated by the Sublime. (It seems a slippery qualification to pursue, but such is the entire operation of conducting/mounting a search for the Sublime.) The pastoral scenery in Poussin's most renowned paintings have a furtive 'interior' life, a metaphysical je ne sais quoi, above and beyond anything painterly, allegorical, figurative or simply mimetic. The landscapes are not sublime; they are imbued with the Sublime, which is always already outside any system of representation or figuration. Marin is precise in stating that the Sublime marks a "fissure" in representation "exposing the immanent lapsing of the ontological power of language". Holy smoke! (Zut alors!)

It is here, in this ultra slippery passage regarding traces, gaps and absences, that Pascal makes an appearance in Marin's critique. In Pascal's Pensées the mind encounters "the infinite terms that announce the [S]ublime" within words (e.g., nouns) and within the infinite fields, folds, factors, different conditions, points of view, objects and 'what have you' that comprise a singular 'nominal' figure of speech or thought (or architecture). This resembles Leibniz's famous remarks concerning the hypothetical worlds within worlds within a simple pond (whorls within whorls within whorls, ad naseum, to dizzying effect/affect). Leibniz, then, to save his baroque soul, departs into calculus and produces the ultimate instrumental system for calculating the depth of the world. No such finely-calibrated baroque machine, however gotgeous, will do for Pascal. With Pascal an entirely different conclusion is drawn. In Pascal we see the emergence of the language of incommensurability that haunts present-day post-structuralism (or, at least, this is Marin's great rhetorical trick). It would seem that Derrida's conceptual whirligigs -- e.g., 'differance' and 'trace' -- originate with Pascal. "This vision of an ever-expanding field of differences works in language just as it does in perspective. Language functions as an open-ended field of differences in which man's being is articulated in acts of meaning, in relations formed by discourse among discrete units in that field. Since the number of potential distinctions and propositions is limitless, the full range of semantic possibility can never be circumscribed. Thus language bears the mark of the same constitutive gap that structures perception -- that of the [S]ublime, the infinite." Here too, after all, is the source of much of Jean-Luc Marion's musings on the same subject, transposed into a discussion of "saturated phenomenon" in The Crossing of the Visible and Being Given.

It is here, in this ultra slippery passage regarding traces, gaps and absences, that Pascal makes an appearance in Marin's critique. In Pascal's Pensées the mind encounters "the infinite terms that announce the [S]ublime" within words (e.g., nouns) and within the infinite fields, folds, factors, different conditions, points of view, objects and 'what have you' that comprise a singular 'nominal' figure of speech or thought (or architecture). This resembles Leibniz's famous remarks concerning the hypothetical worlds within worlds within a simple pond (whorls within whorls within whorls, ad naseum, to dizzying effect/affect). Leibniz, then, to save his baroque soul, departs into calculus and produces the ultimate instrumental system for calculating the depth of the world. No such finely-calibrated baroque machine, however gotgeous, will do for Pascal. With Pascal an entirely different conclusion is drawn. In Pascal we see the emergence of the language of incommensurability that haunts present-day post-structuralism (or, at least, this is Marin's great rhetorical trick). It would seem that Derrida's conceptual whirligigs -- e.g., 'differance' and 'trace' -- originate with Pascal. "This vision of an ever-expanding field of differences works in language just as it does in perspective. Language functions as an open-ended field of differences in which man's being is articulated in acts of meaning, in relations formed by discourse among discrete units in that field. Since the number of potential distinctions and propositions is limitless, the full range of semantic possibility can never be circumscribed. Thus language bears the mark of the same constitutive gap that structures perception -- that of the [S]ublime, the infinite." Here too, after all, is the source of much of Jean-Luc Marion's musings on the same subject, transposed into a discussion of "saturated phenomenon" in The Crossing of the Visible and Being Given.We dare infer from these slim discoveries, and we'll drop it immediately if challenged by certified, bonafide, die-hard Pascal scholars, that this all has huge implications for landscape architecture, a field that borrows 'structures' -- natural and linguistic -- left, right, up and down. And it does so shamelessly (out of necessity). By so borrowing, landscape architecture surpasses architecture as the indeterminate artform par excellence. (We feel a twinge of sympathy for architects, given that they try so hard to appropriate landscape but always fail due to the implicit embarrassment of riches that they feel in approaching mistress nature.) Such profound indeterminacy suggests that landscape architecture might yet (always-already has) encode or collect, in a 'constellation' (pace Agamben's notion of ideas as constellations), the greatest number of signifiers (referents) without the attendant (usual) recourse to artificial figures, geometry and/or other meta-narrative structures and analogues. Here, then, we detect, trembling, a potentially earth-shattering opening to the infinite (and Eternity) that is rarely tackled in present-day instrumentalities (articles of insturmental reason) -- landscape, architectural and urban design included.

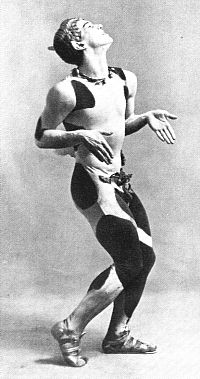

According to Marin, it is in Pascal's very famous remarks regarding the two infinities (in "Disproportion de l'Homme", in the Pensées) that an anticipation of Kant's third critique (The Critique of Judgment) is evident. (We apologize profusely for bringing up Kant but simply, as modernists, can't help it.) The two forms of imagination broached in Pascal's Pensées -- 'reproductive' and 'productive' -- are established as means of approaching/apprehending the world. 'Reproductive' imagination is essentially the oldest game in the book; that is, classical mimesis or imitation. The latter, 'productive' imagination, is a superior force that comes to an apotheosis of sorts, in Pascal's estimation, in geometry. Mimesis is considered by Pascal "the mistress of error and falsehood". This is so, no doubt, for the very reason that it may not approach the Sublime. The latter, the 'productive', is the realm of phantasia (phantasm) and the daemonic (in the Platonic sense). It is, after all, the interior 'abstract' compositional traits of Poussin's paintings that adumbrate the Sublime, not the picturesque or archaic landscape, nor the mythological, often tragic subject matter. Pascal eventually gets round to disowning geometry (a preliminary form of abstraction), however, since it cannot but generate new conceptions of 'proportionality'. The Sublime, by its hidden 'nature', must transgress "every perceptual limit of the imagination". Proportionality is a curse that results in "lassitude" and "monotony" (or melancholy). "Here theoretical consciousness encounters its pathos [...] The melancholy pathos of the indefinite discovers itself to be geometric knowledge."

According to Marin, it is in Pascal's very famous remarks regarding the two infinities (in "Disproportion de l'Homme", in the Pensées) that an anticipation of Kant's third critique (The Critique of Judgment) is evident. (We apologize profusely for bringing up Kant but simply, as modernists, can't help it.) The two forms of imagination broached in Pascal's Pensées -- 'reproductive' and 'productive' -- are established as means of approaching/apprehending the world. 'Reproductive' imagination is essentially the oldest game in the book; that is, classical mimesis or imitation. The latter, 'productive' imagination, is a superior force that comes to an apotheosis of sorts, in Pascal's estimation, in geometry. Mimesis is considered by Pascal "the mistress of error and falsehood". This is so, no doubt, for the very reason that it may not approach the Sublime. The latter, the 'productive', is the realm of phantasia (phantasm) and the daemonic (in the Platonic sense). It is, after all, the interior 'abstract' compositional traits of Poussin's paintings that adumbrate the Sublime, not the picturesque or archaic landscape, nor the mythological, often tragic subject matter. Pascal eventually gets round to disowning geometry (a preliminary form of abstraction), however, since it cannot but generate new conceptions of 'proportionality'. The Sublime, by its hidden 'nature', must transgress "every perceptual limit of the imagination". Proportionality is a curse that results in "lassitude" and "monotony" (or melancholy). "Here theoretical consciousness encounters its pathos [...] The melancholy pathos of the indefinite discovers itself to be geometric knowledge."Marin, then, in an exquisite rhetorical coup d'état, brings Pascal's greatest revelation to bear: "[T]o 'the art hidden in the depths of the human soul' responds a nature that, enshrouding itself in its depths, never relents as it develops indefinitely its present, yet unrepresentable, infinity: its totality." The two infinities become, in this scenario, a melancholy uber-geometry, a human and divine inexaustibility, the unbridgeable gap between the product of the theoretical imagination and the inexhaustible production of nature. To escape, pathos yields to ethos, in Pascal's fertile brain. He leaps the fence and discards all instrumental systems (geometry, rhetoric, etcetera) "to make reflections that are worth more than all the rest of geometry". This is the unhinging of language itself and a stepping out into a virtual landscape of extraordinary indeterminacy. To bring it home, so to speak, in the production of landscape, it would constitute a "sublime writing", as it did for Poussin, but 'it' will always be provisional. Here, maybe, is the true meaning of the avant-garde.

There is a glimpse, here, between these towering conceptual peaks, of a great, somewhat mystical hidden art, Pascal's "art hidden in the depths of the human soul". (In Schiller's romantic take on this, what matches the divine sublime, in the human being, is 'Will'.) Could this sigilistic artform be approached through a utopian landscape architecture? Marin has also written (elsewhere) about utopia as a linguistic (literary) means of unearthing ideology -- as a perennial critique of the status quo. Pascal's cryptic claim that "man surpasses man infinitely", suggests, perhaps, that human imagination fails to supply an object to the fullness of the Sublime simply because s/he is a work in progress. Here, then, are echoes (back and forth) with Marion's idea of saturated phenomenon. Yet Marin suggests that we might, in fact, discover in ethics (ana-praxis) a suitable ground for approaching this divine (daemonic) surplus. This is the unavoidable wager, a gambit alluded to by innumerable writings after Pascal, opened up by Pascal's chiasmus. If the instability of signs implies an infinite regress -- i.e., signs are essentially empty or retain only a trace of the signified -- it is in the nature of language itself that this absence occurs. Might language be renovated toward a rapprochement with the Sublime? Might it not require constant renovation? Marin proposes that this condition of inadequacy is a "strange ecstasy", and in so doing offers a form of compensation -- the contemplation of the Sublime as an opening onto other frontiers, perhaps more fruitful and perhaps more alarming than anything instrumental systems or everyday experience may ever offer. Perhaps it is all a fairy-tale, or vain imaginings. Such is the realm of phantasy and redemption. Such may also be the path to the hidden, rumoured back door to 'Eden'. (GK - 2001/2004)

There is a glimpse, here, between these towering conceptual peaks, of a great, somewhat mystical hidden art, Pascal's "art hidden in the depths of the human soul". (In Schiller's romantic take on this, what matches the divine sublime, in the human being, is 'Will'.) Could this sigilistic artform be approached through a utopian landscape architecture? Marin has also written (elsewhere) about utopia as a linguistic (literary) means of unearthing ideology -- as a perennial critique of the status quo. Pascal's cryptic claim that "man surpasses man infinitely", suggests, perhaps, that human imagination fails to supply an object to the fullness of the Sublime simply because s/he is a work in progress. Here, then, are echoes (back and forth) with Marion's idea of saturated phenomenon. Yet Marin suggests that we might, in fact, discover in ethics (ana-praxis) a suitable ground for approaching this divine (daemonic) surplus. This is the unavoidable wager, a gambit alluded to by innumerable writings after Pascal, opened up by Pascal's chiasmus. If the instability of signs implies an infinite regress -- i.e., signs are essentially empty or retain only a trace of the signified -- it is in the nature of language itself that this absence occurs. Might language be renovated toward a rapprochement with the Sublime? Might it not require constant renovation? Marin proposes that this condition of inadequacy is a "strange ecstasy", and in so doing offers a form of compensation -- the contemplation of the Sublime as an opening onto other frontiers, perhaps more fruitful and perhaps more alarming than anything instrumental systems or everyday experience may ever offer. Perhaps it is all a fairy-tale, or vain imaginings. Such is the realm of phantasy and redemption. Such may also be the path to the hidden, rumoured back door to 'Eden'. (GK - 2001/2004)Blaise Pascal, 1623-1662 (Little Blue Light) ...

Regarding the sign (and song) of infinity doubled, see Double-Black Cat (07/17/04) ...

POSTSCRIPT(S) / SMALL PRINT

1/ News from 'The Castle'

"It cannot suffice to invent new machines, new regulations, new institutions. It is necessary to change and improve our understanding of the true purpose of what we are and what we do in the world. Only such a new understanding will allow us to develop new models of behavior, new scales of values and goals, and thereby invest the global regulations, treaties and institutions with a new spirit and meaning." --Václav Havel (2001), Forum 2000 - Prague

2/ Naming Names / Mirror-Writing

2/ Naming Names / Mirror-WritingAND, Pierre Bourdieu, Méditations pascaliennes (Paris: Seuil, 1997)

3/ "If it is true that there is an origin of language and if it is true that the origin of language is other to the uttered experience of language, then the origin is irreparably lost and unreachable. Unless, of course, one wishes to locate that origin in the unconscious and spiritual domain of subjectivity and postulate the existence of an unconscious and spiritual language as well as an unconscious and spiritual being separate from the actual and present being. Here the conflation between subjectivity and language is perfect; a conflation that appears to confirm the history of language, subjectivity and knowledge. If this were the case the expression ‘non mi viene la parola would mean nothing more than ‘my unconscious self is not coming to my conscious self, bringing forward the unconscious and potential language that is stored away for my own use.’ But if this were the case, how would it be possible for an unconscious language to be called into existence and actuality at any given moment? The existence of language in the realm of utterance and its situatedness in actuality denies the representation and interpretation of the origin of language as the locus of the spiritual and the unconscious. The surreal, the ‘unconscious,’ the magic language is not the one that appears, uncontaminated and pure, straight out of its original home, it is not the origin. Rather, it is a word and a language that arrive on the plain of presentability via a different route than ordinary language." Paolo Bartoloni, The Paradox of Translation via Benjamin and Agamben, CLCWEB 6.2 (2004)

4/ Regarding the trajectory of Wordsworth's concept of the Self as it confronts or reads itself into the world (as in the Prelude), that is via the interdependence of noumena and phenomena, see Harold Fromm's review ("Overcoming the Oversoul: Emerson’s Evolutionary Existentialism") of Lawrence Buell's Emerson in The Hudson Review (Spring 2004). The seemingly archaic nature of the 'self' written into the works of Wordsworth came to later expression in Emerson's philosophy of self-reliance, especially in his essay "Nature" (prior to his swerve into monism), was picked up by Nietzsche (an avid reader of Emerson in his youth), and was subsequently folded into the twists and turns of Heidegger's Being and Time. To follow this thread, cliquez ici ... / It is, perhaps, to Novalis that we must turn for the Romantic origin of this concept of the Self (a topological self) ... Wordsworth's Prelude was published in 1805. Novalis, Prince of Romantics, died (however prematurely) in 1801. / Regarding Kant's concepts of noumena and phenomena, or that which Romanticism strenously objected to, cliquez ici ... For additional aspects of this nominally 'Romantic' concept of the Self and its Other ('The World'), see the essay on Dilthey and Gadamer ("'To Be Alive When Something Happens': Retrieving Dilthey's Erlebnis") in Janus Head 3:1 (Spring 2000) ... It is the origin of the term Erlebnis, and what Gadamer consequently did with/to it (especially in Truth and Method / Wahrheit und Methode, 1960), that is at stake in this essay-as-question-mark ... / For present-day objections to transcendental subjectivity (and philosophical aesthetics, in general), follow the link on the Journals / Zines Page (Yellow Pages) to the now-infamous, 2003 anti-theory (post-theory) "editorial symposium" held under the auspices of Critical Inquiry in Chicago ...

/S/OME-THING ELSE ALTOGETHER

/S/OME-THING ELSE ALTOGETHERHaving checked, then, with the wind and the rain, Marcel Proust, Marie-Henri Beyle (/S/tendhal), Jean-Luc Marion, several small birds, and the dark-eyed moles (which toss up, under the cover of darkness, small mounds of fertile soil in the garden), what you no doubt hear calling (from near and far), what you see in the corner of your eye, and what is always-already next, is, indeed, /S/ome-thing Else ... (06/28/04)

SUPPLEMENTAL DOCUMENTS

Pays de Tendre: /S/ome-thing Else (RTF / 60 KB)

Sublime Scare Tactics (RTF / 36 KB)

Sublime Aesthetics?: The Syllabus (RTF / 91 KB)

Letter to Paolo Bartoloni (RTF / 51 KB)