The upsurge in prison population and overcrowding coupled with the movement to reduce the size and scope of government opened the window of opportunity for correctional privatization. Private prisons have emerged as an expedient solution, helping to neutralize the opposing forces impinging on government to do more with less. But is it good public policy? Beyond its expediency in ameliorating an immediate crisis, is prison privatization a good idea in the long run?

Prison privatization evokes both support and opposition from two levels: ideological and substantive. Arguments from an ideological perspective tend to view private prisons as a secondary consequence of a larger social issue, and opposition (or support) stems from one's perspective on that issue rather than on the substantive merits of the prisons themselves. For example, libertarians, who argue for minimal governmental involvement in social institutions, typically support policies which reduce the span of governmental control. Since the contracting out of prison operations reduces (or at least impedes increasing) the size of government, libertarians tend to support prison privatization. On the other hand, civil rights advocates are alarmed by the growth of the criminal justice system, particularly in its disproportionate effect upon people of color, and applaud measures which limit the coercive powers of the state. Since private prisons increase the coercive options available to the state, civil rights advocates tend to oppose prison privatization. Much of the debate over prison privatization is being waged on an ideological level, depending upon political philosophy regarding the extent of personal and economic self-government believed to be appropriate in society. An interesting challenge to the reader would be to take the World's Smallest Political Quiz (Nolan, 1971) to see where you line up ideologically (the quiz takes less than two minutes to complete. My hunch is that those of you who score high on self-government in economic matters probably support privatization. Those of you who score in the low range likely oppose it. To see where the author scored on the quiz, press here). The important point is that ideological issues quite removed from the individual prison cells in public and private prisons are framing the overall debate over correctional privatization. We'll now turn to the major players players who are lining up on both sides of the debate. First,

The American Civil Liberties Union's (ACLU) position on prison privatization is summarized by Jenni Gainsborough, the public policy coordinator of the ACLU's National Prison Project:

I'm completely opposed to the concept of private prisons. The most extreme sanction the state has against the individual, short obviously of the death penalty, is imprisonment, and that should not be turned over to an organization whose primary concern is the profit of its shareholders. ACLU Press Release(9/30/97).

The ACLU voices an anti-privatization rhetoric containing

the implicit assumption that prisoner rights will be

compromised in the drive to make money. It is assumed that profit-making

supersedes running a good program as the primary motivation

of private operators. In practice the ACLU, and other activist organizations opposing prison privatization, target their opposition on three prison reform issues:

1. Prisoner's Rights Litigation. One of the major advantages of private prisons cited by privatization advocates is the relative absence of prisoners rights litigation and court orders involving private prisons. As the National Center for Policy Analysis notes, "not a single private facility is operating under a consent decree or court order as a consequence of suits brought by prisoner plaintiffs. Yet about 75 percent of American jurisdictions now have major facilities or entire systems operating under judicial interventions (NCPA, 1995)." The legal exposure that government-operated prisons contend with is relatively absent (so far) in private operations. This has translated into the possibility of greater management flexibility and lower administrative costs in the private sector. However, these two advantages may be eroding as evidenced by recent legal and legislative developments.

While a body of case law involving prisoners in private prisons is beginning to emerge, correctional privatization remains a relatively new phenomenon and the law is murky in this area, although the general guideline has been that prisoners in private facilities have exactly the same rights as public facility inmates. Still, the ACLU's success in advancing prisoners rights has been attained by challenging public agencies and facilities where substantial legal precedent has been established. In the private sector, the extent of private agency immunity from civil rights lawsuits is unclear, and this uncertainty concerns the ACLU.

Thus, the ACLU filed an amicus curiae (friend-of-the-court) brief in the case of Richardson et al. v. McKnight, which was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court on June 23, 1997. Ronnie Lee McKnight, an inmate at the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) operated South Central Corrections Center in Clinton, Tennessee, sued the company in district court, alleging that two CCA guards had handcuffed him too tightly during transport, causing serious injury. CCA argued for dismissal of the case, claiming that, as agents of the state in operating the prison, their employees should be protected under the doctrine of "qualified immunity" which shields state officials (and correctional officers) from liability in all but the most serious cases of abuse. The district court dismissed CCA's plea, the Sixth Circuit affirmed the lower court's decision, and CCA appealed to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court agreed with the lower courts, stating that qualified immunity extends to government agencies but not to private corporations contracting with the government. While the Supreme Court did not take a position on the prison privatization issue, the ACLU's brief clearly states their own:

Private prisons primarily exist to make a profit and not to serve the public [and] private prisons have financial incentives to cut corners at the expense of inmates' constitutional rights (ACLU, 1996).

Although the ACLU continues in its blanket opposition to private prisons, the Richardson case may in fact grant prisoners the right to go deeply into the pockets of private corporations that abuse them, a right that is limited in government prisons.

Defense against prisoner's rights litigation translates directly into financial expense for governmental authorities but these costs may be coming down in response to recent legislation. In April, 1996, the Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA) was signed into law by President Clinton. Strongly opposed by the ACLU, the PLRA was a rider in the Balanced Budget Down Payment Act and sets several procedural limits on prisoners bringing claims to federal courts. For example, it limits prisoners ability to proceed with a lawsuit in forma pauperis (without payment of fees), requires greater use of administrative remedies by prisoners prior to filing suits, and enables the courts to revoke good time credits from prisoners who file frivolous lawsuits or who present false testimony in court (ACLU National Prison Project).

In effect, if the new law survives ACLU challenges to its constitutionality (the ACLU is actively recruiting cases to challenge the PLRA), it could reduce government costs of operating prisons and erode the modest cost advantage enjoyed by private prison operators.

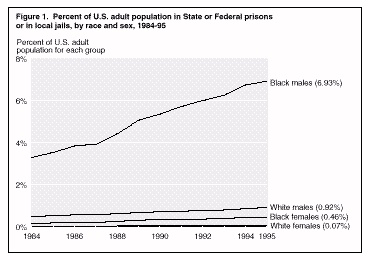

2. The Prison-Industrial Complex. The near doubling of the U.S. jail and prison population in the past ten years (BJS, 1997) has been disproportionately balanced on the backs of African-Americans. A dubious milestone was reached during 1996 when, for the first time in U.S. history, the absolute number of Black prisoners surpassed the number of Whites incarcerated in prisons and jails (Brown, 1996)). As the following BJS (1997) chart reveals, nearly 7% of all adult Black males were in jail or prison by the end of 1995:

The causes of this increasing disproportionality (such as drug policy) are beyond the scope of this analysis (see, for example, BJS Midyear 1996 report, that notes a 707% increase in incarceration of African-Americans for drug offenses from 1985-1995 compared to an increase of 306% for Whites). For the ACLU, and several other opponents of privatization, the problem of racial discrimination in incarceration is viewed in light of what has been termed "the prison-industrial complex." In reviewing an article from Emerge magazine, the ACLU notes:

African-Americans are grist for the fast-growing prison industry's money mill. Crime pays. It certainly does pay for those who profit from the expanding correctional-industrial complex. They include private prison operators, those who build and supply prison cells, the suppliers of food and medicine - and guards, who recently have realized a new level of clout. Companies vie for everything from building contracts to the right to sell hair products to prisoners, while economically strapped towns see prisons as a source of jobs. (ACLU Press Release, 9/30/97).

The dramatic increase in prisoners over the past ten years has spawned not only private prisons but a concomitant increase in marketing and sales of the entire panoply of products and services related to prison operations as well as employment in the correctional industry. This "prison-industrial complex," a play on Eisenhower's coinage of the term "military-industrial complex," has become a focus of criticism from the ACLU and other left-of-center organizations on the political spectrum. One such organization, Justice Net, maintains a web page devoted to "news, stats, and resources on the prison-industrial complex, and the human rights and economic crisis which it causes." Justice Net includes links to Critical Criminology, the journal of the Critical Criminology Division of the American Society of Criminology. These sources are short on specific information regarding prison privatization, but express the general view that prison privatization is a cog in the overall machinery of oppression of minorities and the poor and thus a suitable target of opposition. Similar information can be found at Covert Action Quarterly, which devotes a page to an article on "Private Prisons: Profits of Crime," from its Fall, 1993 edition (no. 46). This article expresses the ideological assumption that the profit-motive of private providers will drive them to skimp on providing for basic needs of prisoners but offers no data to support the claim. To the contrary, the article implies that private prisons may in fact be better managed, safer places for prisoners than public facilities: "the record so far, however, shows that compared to the murderous outbreaks in state penitentiaries, incidents of violence, riot, escape and the like have been relatively rare in the private prisons." (CAQ, 46). Another organization, the U.K. based Prison Reform Trust, maintains a monthly newsletter entitled Prison Privatisation Report International (Note: this is a paid subscription service) which is arguably the most thorough and up-to-date resource on prison privatization around the world. Also left-leaning, the report provides detailed information on the status of private prison contracts and encapsulates news reports from around the world critical of privatization.

Regardless of the ideological take on the "prison-industrial complex," there is no doubt that the huge upsurge in prison population has generated considerable investment in all aspects of prison related business, and private prison speculation is no exception. For example, a recent article in Fortune Magazine (Fortune, Sept. 29,1997), entitled "Getting Rich with America's Fastest-Growing Companies," ranked Corrections Corporation of America, the largest private operator of prisons in the world, as the 67th fastest growing small company in the U.S., with the value of its stock appreciating some 746% over the past three years. To be sure, "crime does pay" as the ACLU rhetorically observes.

3. Prison Labor. The privatization controversy reaches a new level of complexity when the issue of privatizing prison labor is considered. The issue of prisoners working to produce commercial products while incarcerated has a long, controversial history in the U.S. and is severly restricted by state and federal legislation. While a thorough discussion of the history of prison labor is beyond the scope of this paper, the practice was common in the U.S. until 1929 when Congress passed the Hawes-Cooper Act and related legislation which banned prison-made goods from interstate commerce. In response to lobbying efforts by organized labor, by 1940 virtually every state had passed legislation banning the importation of prison-made goods from other states (Clear and Cole, 1997). The issue is devisive within the community of privatization opponents, with several opponents (such as the ACLU) voicing ambivalence on the issue. On the one hand are correctional reformers who are pressing to provide prisoners with more meaningful, lucrative, and rehabilitative opportunities to actually "learn a trade" while behind bars. On the other hand are those who voice concern over exploitation of prisoners and over taking away jobs from law-abiding citizens. The notion of "private prisons" contracting out the labor of their inmates to other private companies adds even greater complexity to the dilemma. An excellent discussion on this complex issue by Steven Elbow (1995) can be referenced by clicking here. This issue leads us to another group of privatization opponents, the American labor movement.

Understandably, The American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, the largest union representing employees in the public sector, is concerned about the effect that privatization in all levels of government is having on its membership. AFSCME maintains a web page entitled Government For Sale which presents arguments against contracting out of government services and case histories of negative privatization experiences. In the specific area of corrections, AFSCME includes a very brief report entitled Private Prisons: Cutting Costs by Cutting Corners which cites selected negative findings on private prisons from a Tennessee government sponsored comparison of public and private prisons (see item # 10 in the Evaluation section of this web page). The report notes a higher rate of inmate injuries and staff use of force incidents in the private prison. The AFSCME report neglects to note the overall findings of the evaluation that the two public and one private prison were operating without significant difference in security, safety, and overall program quality.

The AFL-CIO, the umbrella organization representing organized workers in all sectors of the labor force, has not published an official position opposing prison privatization but supports the efforts of local AFL-CIO shops engaging in anti-prison privatization efforts. According to the AFL-CIO News, the organization is using its web page to help local chapters resist privatization, including prisons:

The Internet has helped the Service Employees, California State Employees Association arm itself in a fight over privatizing the state's prisons (AFL-CIO News, July 12, 1996).

The AFL-CIO's "Union Summer" project of 1996, an effort that recruited thousands of young union activists to engage in organizing activities, included local projects directed at opposing prison privatization. As AFL-CIO staffer Muriel H. Cooper explained:

The summer of 1996 will be remembered as one that made a difference in the lives of thousands of working families and young people who benefited from Union Summer. In Georgia, activists will help organize state workers in an effort to fight against privatization by Gov. Zell Miller (D), who, after wooing union voters, is trying to give away their jobs. The governor supported legislation to privatize prisons and the Georgia War Veterans Home, according to Stewart Acuff, president of the Atlanta Labor Council. Members of Service Employees Local 1985 feel betrayed. "Workers will be put out of jobs," he said, "and those that aren't will see lower wages and benefits." (AFL-CIO News, June 7, 1996).

A March 22, 1996 edition of the AFL-CIO News expressed the general alarm of the organization over job loss through corporate and government downsizing and listed specific effected areas in early 1996, including the trimming of 340 jobs by the New Jersey Department of Corrections which was privatizing their prison medical care program.

Several labor unions representing correctional officers have joined the Corrections and Criminal Justice Coalition (CCJC), an organization created to represent the interests of public employees in the criminal justice sector. Avowedly anti-privatization, the CCJC has created a standing committee on Privatization and Legislation to advance this agenda. The CCJC lists the following dues paying members:

The CCJC anti-privatization message (view) is ideological, presenting rhetorical criticism but no substantiated information about privatization outcomes.

Aside from the potential loss of union membership through privatization of prisons, organized labor's opposition stems from the assumption that wages and benefits of correctional workers will be lower in the public than in the private sector, as profits take priority over working conditions. However, the current state of data on this key point is slim at best. In one of the only studies which compared such salaries (Logan, 1996 - see Evaluation section), the average salary of staff in the private prison was actually higher than salaries at the state prison, although not significantly so. Likewise, the study reported a higher quality of management/staff relations in the private prison than in the state facility.

In summary, ideological concerns of prison privatization opponents that both prisoners and corrections workers will be exploited by private opperators (i.e., that they will be exploited more in private prisons)is certainly a concern that demands vigilance, but one which has not been borne out through research. Let's turn now to a discussion of the major proponants of prison privatization.

The driving force behind correctional privatization is, quite simply, elected officials. The sheer cost of incarcerating a prison population that is growing by 7.8% per year (see Emergence section) has meant that the share of the U. S. gross domestic product (GDP) devoted to the criminal justice system has more than doubled since 1965 (NCPA, 1997). Jerome Miller recounts the phenomenal growth in criminal justice spending since 1970:

Federal, state, and local funding of the justice system literally exploded in the two decades leading up to the 1990s. Average direct federal, state, and local expenditures for police grew by 16%; courts by 58%; prosecution and legal services by 152%; public defense by 259%; and corrections by 154%. Federal spending for justice grew by 668%; county spending increased by 710.9%; state spending surged by 848%. By 1990, the country was spending $74 billion annually to catch and lock up offenders (Miller, 1994).As prisons consume more and more scarce tax revenue, privatization is being advanced as a means to help curb a seemingly endless drain on government revenue.

A call for the privatization of various services currently operated by government agencies has worked its way into the official platforms of the Republican, Democratic, and Libertarian parties in the U.S. The 1996 "platforms" adopted by all three National Commitees (the RNC, the DNC, and the LNC) express a need to reform the federal government with privatization playing a part, albeit under the guise of different language. These general policy statements do not specifically address the privatization of correctional services but promote privatization as part of a larger agenda.

The 1996 Republican Platform is the most direct in advocating the use of privatization at all levels of government:

Republicans believe we can streamline government and make it more effective through competition and privatization. We applaud the Republican Congress and Republican officials across the country for initiatives to expand the use of competition and privatization in government. It is greater competition - not unchallenged government bureaucracies - that will cut the cost of government, improve the delivery of services, and ensure wise investment in infrastructure. A Dole administration will make competition a centerpiece of government, eliminating duplication and increasing efficiency (RNC Platform, 08/12/96).

The Democratic Party shies away from using the term "privatization," preferring the phrases "reinventing government" and "partnerships with the private sector" to advance their privatization message, and the "National Performance Review" as the method of implementation. As the 1996 Democratic National Platform notes:

In the last four years, President Clinton, working with the National Performance Review chaired by Vice President Gore, has cut the federal government by almost 240,000 positions, making the smallest federal government in 30 years. Over the next four years, the Democratic Party will continue to make responsibility the rule in Washington: cutting bureaucracy further, improving customer service, demanding better performance, holding people and agencies accountable for producing the best results, ensuring all Americans have access to high quality public services, whether they reside in inner cities, suburbs, or rural communities, and forging new partnerships with the private sector including small, minority, and women-owned businesses, and with state and local governments to enhance opportunities for all Americans from technology to transportation to travel and tourism (DNC Platform, 08/27/96).

Like the Democrats, the Libertarian Party, ostensibly the most ardent advocate of privatization, does not use the "p" word in the 1996 National Platform of the Libertarian Party, offering instead the following language:

We advocate the termination of government-created franchise privileges and governmental monopolies for such services as garbage collection, fire protection, electricity, natural gas, cable television, telephone, or water supplies. Furthermore, all rate regulation in these industries should be abolished. The right to offer such services on the market should not be curtailed by law (LNC Platform, July, 1996).

In advancing their specific program, the Libertarians call directly for the privatization governmental services to individuals, such as the Medicare and Medicaid programs, as it promotes their general ideological belief in maximizing the rights of individuals.

Regardless of whether it's termed "privatization," "partnership with the private sector," or "termination of government monopoly," the contracting out of traditional governmental services is being promoted by the political parties representing the vast majority of elected state and federal officials in the U.S. In order to examine where elected officials get information on how to actually go about privatizing services, please move to the section on the "decision-making" process.

| TOPIC PAGE | EMERGENCE | ASSESSMENT | DECISION MAKING |

|---|---|---|---|

| IMPLEMENTATION | EVALUATION | REFERENCES | VIRTUAL CONFERENCE |