As we have seen thus far, private prisons and jails are currently housing only about five percent of the U.S. inmate population. Private prisons constitute a $600 million industry which is growing at an annual rate of about thirty percent (NCPA, 1997). No standardized national data base on private prisons is currently in operation although the Privatization Center at Temple University and the Reason Institute are collaborating on a proposal to begin such a project. At present, extensive information on the status of the industry can be found at The Prison Privatization Research Site, a pro-privatization web site hosted by two university professors active in industry research: Charles Logan, at the University of Connecticut, and Charles Thomas, at the University of Florida. Their site contains a number of position papers arguing in favor of prison privatization as well as data from peer-reviewed research.

The Private Corrections Project, Center for Studies in Criminology & Law, at the University of Florida conducts an annual census of the state of prison privatization and provides links to the many companies entering the growing industry. The census lists the following year end 1996 data on the state of the industry: as of 12/31/96 there were 84,272 beds in 132 facilities under contract or construction as private secure adult facilities in U.S., U.K., and Australia, with gross operating revenues for 1996 of over $500M.

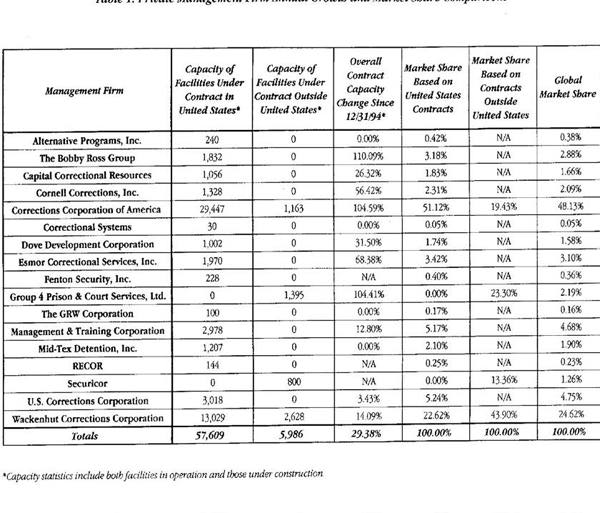

Additionally, the authors provide a chart listing the private

companies involved in private prison operation world wide at year-end

1995:

The two largest companies, Corrections Corporation of America and Wackenhut Corrections Corporation, together control nearly 75 percent of the total private facility capacity and are both publicly traded corporations with worldwide operations (for current NYSE information on these companies, refer to CXC for Corrections Corp. of America and WHC for Wackenhut). The Private Corrections Project provides information and links to the "big two" as well as the other companies currently operating private prisons.

An examination of the current privatization battle being waged in the state of Florida, and the involvement of the "big two" private prison operators, provides a good case study of implementation issues surrounding correctional privatization.

According to information provided by the Florida Corrections Commission in its 1996 Annual Report, correctional privatization began in Florida in 1985 following the passage of Chapter 85-340, Laws of Florida which authorized both the Department of Corrections and counties to contract with private entities to operate and maintain state or county detention facilities. (Recall that 35 states now have similar legislation (NCPA, 1997) and that the Heartland Institute (1997) provides a model legislative bill to those state lawmakers desiring to pass such enabling legislation). Bay County, Florida, was the first county to "go private" under the new legislation, contracting out the operation of the local Bay County Jail to Corrections Corporation of America in 1985.

In 1989, the Florida Legislature passed subsequent legislation authorizing the state Department of Corrections to contract with private entities to construct and operate state prisons. A Request for Proposals (RFP) was issued, requiring that the contracted facility be built and operated "at substantial savings" to the state. Four private firms submitted proposals to the state: CCA, Wackenhut, Pricor, and National Corrections.

Two years of serious haggling ensued, as the respective bidders appealed to the state to clarify the provisions of the RFP. Several addenda were added to the RFP, including a specification that the prison operate at a minimum cost savings to the state of 10 percent. Disagreements over the addenda process led to the filing of formal protests by National Corrections and Wackenhut, essentially disputing the state's methodology in calculating its own costs. Eventually, the proposal was dropped by the Department of Corrections in February, 1991.

In 1990, in separate legislation, the state authorized Gadsden County to enter into a lease-purchase agreement with a private firm to build and operate a close custody, single cell prison on behalf of the state. An RFP was issued in December, 1990 but subsequently withdrawn by the state as the Florida Attorney General's office considered whether the RFP was in compliance with state law. The legal issues were sorted out and the RFP was reissued in October, 1991. In February, 1992, U.S. Corrections Corporation was awarded the contract, but just nine days prior to opening the new facility the DOC decided to house female rather than male inmates in the facility. This led to modifications to the facility which delayed its opening until March, 1995.

In response to the problems and slow pace of the contracting process through the Department of Corrections, in 1993 the Legislature created a separate Correctional Privatization Commission (CPC) for the express purpose of entering into contracts for the construction and operation of private prisons. The CPC is functionally independent of the DOC and is administratively housed in the Department of Management Services.

In December, 1993, the new CPC issued its first RFP for the construction and management of two 750 bed medium security prisons. Eight private firms submitted a total of twelve proposals. Contracts were awarded to the Wackenhut Corrections Corporation, which opened the Moore Haven Correctional Facility in July, 1995, and the Corrections Corporation of America, which opened the Bay Correctional Facility in August, 1995. A subsequent RFP by the Correctional Privatization Commission resulted in the "big two" winning contracts to each build and operate an additional prison; in February, 1997, Wackenhut opened its South Bay facility and CCA opened Lake City (Florida Corrections Commission, 1996 Annual Report).

Currently, Florida houses 96 percent of its 59,851 state inmates (as of January 1, 1997) in 56 public prisons and 4 percent of its inmates in the five private prisons discussed above. The following exhibit, provided by the Florida Legislature, Office of Program Analysis and Government Accountability (Report No. 96-69, March 1997), shows the location of the public and private facilities:

In spite of the relative sophistication of the Florida process, with its separate state agency designed to administer, monitor, and evaluate the private prison industry, the jury is still out on the overall effectiveness of correctional privatization in the state. In the above referenced report, the Office of Program Policy Analysis and Government Accountability (OPPAGA) found that a full accounting of how much money the private facilities are saving the state remains a mystery, impeded by controversy surrounding the validity of cost methodology used to determine the costs of private vs. public facilities. According to the OPPAGA report, in separate comparisons of the costs of the private and public facilities, the Department of Corrections and the Correctional Privatization Commission have reached opposite conclusions: the CPC concluded that the private prisons were saving the state money while the DOC determined that they were not. In guarded language, the OPPAGA report offered this assessment:

Because the outcome of cost comparisons reflects upon the performance of both the Commission and the Department, it may not be reasonable to expect them to work together to develop accurate and meaningful cost comparisons. It will be necessary for an independent third party, such as OPPAGA, to identify comparable prisons and develop methodologies for comparing costs (OPPAGA, 1997).

A discussion of the implementation of correctional privatization in Florida brings us full circle around all of the issues addressed in this web-based public policy debate. Many of the factors discussed in the sections on Emergence and Assessment continue to frame the privatization debate in Florida:

Fortunately, a body of objective evaluations of correctional privatization efforts around the county is beginning to shed light on the fiscal and programmatic outcome of prison privatization. For a discussion of outcomes, move on to the "Evaluation" section.

| TOPIC PAGE | EMERGENCE | ASSESSMENT | DECISION MAKING |

|---|---|---|---|

| IMPLEMENTATION | EVALUATION | REFERENCES | VIRTUAL CONFERENCE |