It's a lot harder than most people think, while at the same time being a lot easier than most players imagine.

This isn't a definitive guide to running a roleplay campaign, this is just what I do.

|

How to run a roleplay game |

|

Prep, prep, prep | Props | Style | | Balancing The Party | Dice | Rules | Rewards |

|

It's a lot harder than most people think, while at the same time being a lot easier than most players imagine. This isn't a definitive guide to running a roleplay campaign, this is just what I do. |

Preparation is the key to a good game. While really experienced GMs can (apparently) run a game with no prep work at all, I would not recommend this. Most of our GMs would have a panic attack at the thought. Prep means how much work you put into the overall campaign; how much of the story you come up with, any props you need, maps, background for the players' characters, etc.

But let's start at the beginning. Every campaign needs a story, which means you need a start, a middle and an end. Or to put it another way; the hook, the pinch and the twist. The hook gets the players hooked into the story, the pinch puts the pressure on and the twist is the final reveal and ending. But where to get the story from? Well, you'll be familiar with the phrase:

'Good artists borrow, great artists steal.'

One of the best starting points is to be a good GM and borrow. Taking a story and translating it directly rarely works as it restricts the players too much. Take the basic concept, and then alter it enough that the players don't recognise it. There's nothing worse than taking the story of what you believe to be an obscure film, book or TV show only to find out that the players know it and spoil the ending.

Preparation should also include deciding on the pacing of the story and when the 'big reveals' happen. There are various methods for this, but I find scene cards to be very useful. Buy some index cards and use each one to describe the important parts of each scene, who the players meet, what they need to do, what information they're going to take away, and even any lines you want to throw in. These cards are also useful to keep the main stats of your NPCs, such as allies or enemies the players will encounter (or just good old fashioned generic henchmen), because there's nothing worse than having to refer to a sourcebook in the middle of combat.

Example of a scene card | Example of an NPC card

In my experience, it's always better to over prepare and bring too much stuff. That way, you've got a place to fall back on in case you need it. On average, I prepare almost twice as much material/plot as I actually use.

Now this is a personal choice here. Some GMs use a lot of props for their games, and some will use none at all. Personally I find them a useful distraction for the players while I'm desperately trying to think of the next part of the story.

Sometimes, as with the Star Wars roleplay sessions, we use miniatures. This is due to Grant's extensive collection of Star Wars minis. These little statues of characters are about an inch high, and are very useful for representing where everyone is in relation to opponents, exits and equipment.

Myself, I like to use a lot of props. Mostly this will be laminated cards to show maps, computer screens or other information important to the game.

Some people will tell you that style is a very important part of the game. I disagree. Style is everything. Whether you adopt a relaxed attitude, or a more formal one in up the GM, but it should match the mood of the group. Some groups prefer to stay in character and jokes are a distraction, others prefer the social gathering and like to joke about while playing.

Now that you've decided on the general style, you need to decide how to run the game. Is it going to be heavily scripted, or dynamic and on the fly?

As the GM, it's your job to help the players create their characters and assist them in rolling up their sheets (creating the stats that they us on their character sheets - picking skills, feats, etc).

This should start early. Give your players plenty of time to come up with ideas for backgrounds, skills they want to take, etc.

There has to be a fine balance between allowing your palyers to have the type of character they want, and having a balanced party for the game. As you can probably imagine, there's little point in having a group of six players who are all slightly different types of soldier. If you need a medic/engineer/thief/wizard, say so.

From the player's perspective, if they need help setting up a character, the best rule of thumb is: invent a character you'd be friends with. If the character is too far removed from their own values and personality, they won't enjoy playing that character.

So, what do you do if no-one wants to take on the role you need for the game?

It's never a good idea to force a player to take on a role in the group. They won't enjoy it, so they won't get as engaged in the game and this will spoil it for the other players.

No GM is complete without a big bag full of various dice. While most players only need a few different varieties for each game, the GM often uses all types of dice during a campaign. So for example, in Dungeons and Dragons a player normally only needs a d20 (or few) and the type of dice for their weapon damage. But the GM would need other dice to determine random events, probability, etc.

The GM also has to set the difficulty check (DC) for the players. This is the relative difficulty of the task being attempted and sets the figure the player must achieve with their dice roll. The player would then roll their DC dice (normally a d20) and add any bonus they get. While this is often a simple decision, picking a lock say, often it involves a fair bit of mental arithmetic, most often during combat. Let's look at an example:

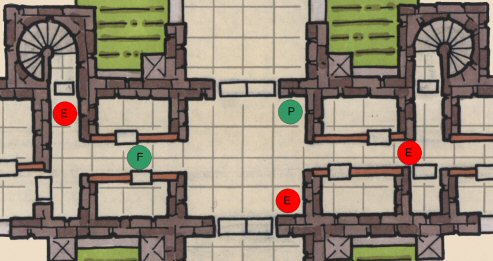

Here the players are in green, and the enemies are in red. Frazer(F) is on the left and Paul(P) is on the right.

Frazer has no line of sight on the first enemy near the staircase, has partial line of sight with the enemy in the large room and full line of sight with the last enemy on the far right. Paul only has line of sight with the enemy in the room. He cannot hit either of the two in the corridors without moving.

Frazer is a mage and is casting magic spells, Paul is a ranger and is using a bow and arrow. If we assume the enemies all have basic armour with a bonus, or protection, of two (2).

So, to assign the difficulty checks (DC).

Paul can only attack the enemy in the same room as him. There's no cover for the enemy to hide behind, so he only has to overcome the enemies armour. The standard DC for ranged weaponry would be ten (10), to which we add the enemies armour protection and arrive at a DC of 12. However Paul has a bonus on his bow of +1, so the DC is 11.

Frazer has a choice here. He can attack the enemy that Paul can fight, but that enemy has partial cover from him, so it's harder. Alternatively he can go for the enemy to the far right, but he's further away and is harder to hit also. He can't attack the enemy nearest himself, since that enemy has full cover - unless he moves or has an attack that either partially or completely ignores cover. In a modern combat setting a grenade would be an example of this. Note: Frazer's character might not even be aware of that enemy.

So let's do Frazer's maths.

Enemy in room: DC = 10 + partial cover 3 = 13

Enemy in corridor furthest from Frazer: DC = 10 + one range increment (2) =

12*

Enemy behind Frazer: If Frazer has a spell, like Frost that affects an area,

it may hit the enemy there. His DC would be calculated as the difficulty in

hitting the wall closest to the enemy (10), plus a difficulty modifier for the

spell to hit the enemy (7). Even if successful, the damage would be reduced**.

* Range increments are the range a weapon or spell works at.

It's used to simulate that shooting an object 60 feet away is harder than shooting

an object 30 feet away. Range increments increase in difficulty until they reach

near impossible (even the best sniper in the world can't hit an object more

than a couple of miles away).

**Imagine throwing a flask of acid. An enemy takes more damage from a direct

hit rather than any splash back.

As the GM, you're going to have to know the game rules pretty damn well. Nothing worse than having a player contradict you on a rule call.

Having said that, almost every role play games says the same thing: feel free to ignore the rules. It's often better to have a cinematically satisfying result, rather than sticking rigidly to the rules.

Even if the game rules say "There's no way in hell a player can ever do this. Failure is automatic. Success is impossible." You, as a GM, should never say "You can't do that." At least, not as bluntly. Allow them to try, make a roll for it, maybe even consult a rulebook, before declaring that they've unfortunately failed.

This is not the same thing as saying "Let them try anything." There's no way a pistol on a planet can take out starship in orbit. Telling the player that the weapon isn't powerful enough, or that they lack the skill or the time is fine.

Player rewards are an integral part of the GM's job. Mostly, the players are rewarded with experience points (XP). XP is banked and used to level up, or advance, the character once enough has been accumulated.

Other rewards can be considered. If it's too early to let the players advance, they can be given unique equipment or similar rewards. Normally these are customised to the player's wishes, such as laser blasters incorporated into gauntlets, or a sword that gives extra damage.