| the truth, as seen by... | |||

| Navigate by clicking the directors name: Godard and Herzog | |||

Along with what I have wrote here, I have included a complete trascription of the Werner Herzog Workshop with Roger Ebert, and the Minnesota Declaration. Click the underlined for links to those pages.

Few directors today possess the tendancy for the eloborate today as Werner Herzog. Many people love him, while many despise him. Harmony Korine for instance, the first American to produce a film conforming to the Dogma 95 (Dogme) standards, attributes Herzog as major influence and cast him in his most recent movie. Love him or hate him, he is quite hard to ignore.

Herzog is proponent for change in the current language of cinema. He despises the new school of reality film, television, and news. Herzog remarks, “Contrary to the claim of Cinema Verité, the truth about the human condition is poetic and ecstatic, can be reached only through fabrication, imagination and stylization: A new language of images has to be developed” (http://www.egs.edu/wernerherzog.html). Remarkable statement, to say the least. But what is to be learned by this sort of claim?

It apears that Herzog’s persona has completely taken over. When he talks, it is almost as though he is compelled to say something contradictory. For example, Roger Ebert asked Herzog of the extreme relationships his characters share with society. He brings up Kaspar Hauser, a film of a boy brought up in issolation who was completely cut off from society. Ebert comments on him being an outsider. "But he is not an outsider:” Herzog decrees, “he is the very center, and all the rest are outsiders! That is the point of the film” (Herzog Workshop Transcription). This is definitely not an isolated instance.

If that is not enough he continues, “I don’t know exactly how many of you in this country also think that Kaspar is just some kind of a bizarre strange figure, but, if you do, it’s exactly the same thing that has happened with audiences, for example, in Germany. There's so much hatred there against my films that you probably wouldn’t even believe it. AGUIRRE got by far the worst reviews that I’ve seen in ten years for any film, and now for NOSFERATU its still going on and on. In Germany, in my own country, people have tried to label me personally as an eccentric, as some sort of strange freak that does not fit into any of their patterns. And that’s ridiculous. They are insane!” (transcription).

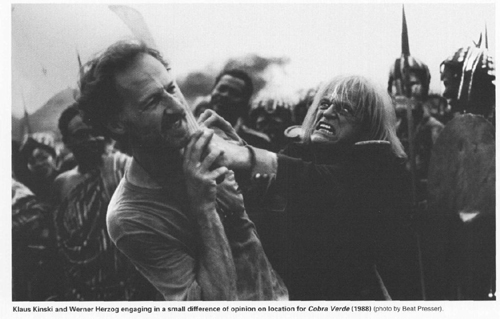

No, it is true that something is to be said by the plight of the outsider about the human experience. But Herzog is a bit extreme, just like his films. The fact that people think what Herzog is doing is insane is precisely the motivating factor for him to do it. However, this is just the tip of the iceberg. Herzog’s most popular leading man, Klaus Kinski, was very troubles indeed. It is as though he purposely hires men who he considers insane to play the leading roles in his films, time and time again. Even in his lesser known films Kaspar Hauser and Stroszek, which both star Bruno S.

Here is how Herzog describes Bruno to Ebert. "Yes, because to make a film with a man like him always has a question of morality involved, and. I think, this was the all-pervading problem that we were aware of during the shooting of both the films that we made with him. Perhaps I have to explain a little bit about Bruno so that you can understand. He was born as an illegitimate child to a prostitute in Berlin, and she really did not want to have a baby so she used to beat him. Then, when he was three, she beat him so hard that he lost his power of speech, and this was a perfect pretext for her to put him away into an asylum for retarded children, a place where he definitely did not belong. He was very much afraid of being in this situation because the other children in that place were either insane or extremely retarded, and he was quite smart. So, at the age of nine, after six years of captivity in there, he started trying to escape, but then, when he finally did escape, he was captured and put into a correctional institution. From there he escaped again and again, and each time he was put into more and more severe correctional institutions. Eventually he developed a long record of minor criminal offenses: for example, for vagrancy or public indecency. One of these times he broke into a car in wintertime when it was snowing, and he slept inside the car. Next morning the police dragged him out, and for this he was given a five months term in prison. And so, all together, he was forced to spend a total of twenty-three years in this kind of captivity, and, as a result, in many ways he has been almost completely destroyed” (transcription). Without this coupling of Herzog and a madman, the filmic process seems impossible to imagine.

On top of the difficult situations that arise from casting mentally unstable leading men, it appears that Herzog also attempts to film the impossible. Ebert asks, “ ... if it was particularly difficult to finance films when you have a fairly unpredictable person in the lead like Bruno, but, then, it occurred to me that you would probably never make a film that was easy to finance because, in addition to the difficulties that are often inherent in film-making, you always make films which seem to be almost impossible to make anyway: for example, AGUIRRE, THE WRATH OF GOD” (transcription). Aguirre was a period piece, set in the Peruvian jungle, starring Klaus Kinski, made for around a quarter of a million dollars US. An unthinkably low amount for that sort of project.

It is interesting that this Workshop came about in 1979, while the pre-production was going on for Fitzcarraldo. Ebert asks, “You said that you were not going to use a plastic boat and a Hollywood mountain, but that you were going to use the eleven thousand Indians to move a real iron ship across those mountains! Would you care to elaborate on that?” (transcription).” And in a imaginable rant Herzog answers, “Yes, but it’s a question that’s not been completely resolved as yet. In theory it would be possible for me to move a ten thousand ton steamboat across the highest mountain with just one single finger. If I had the proper system of pulleys powered by a five hundred volt transmission, then I could easily just pull the rope or simply walk with it for two miles, and the boat would move exactly two inches up the mountain! So, in theory, the problem is easy to resolve. But, in theory, of course, it’s even easy to move this earth out of its trajectory! It can be done in theory. Archimedes has already stated that, not just me, but so far it’s only in theory. Yet, in terms of moving the boat across the mountain, I think it really can be done. We have some very smart people already working out the solution, but we cannot use modern technology because the story takes place around the turn of the century, and so we will have to use just some pulleys and levers and ropes and other simple things, and somehow we’ll do it. You will see. We’ll do it!” (transcription). Of course he does complete this demanding task while filming Fitzcarraldo.

Then Ebert praises Herzog on his triumph with Aguirre. Herzog mearely replies, “Yes, but that’s kindergarten next to what I am now preparing!” (transcription).

It would appear that these are just films about amazingly dynamic individuals who achieve great feats. But there lies the allegory. It is Herzog himself who is the great individual. At least he has built for himself that persona. When Herzog sets out to work with a madman on a film, it serves to reinforce his persona. Also, when he sets out to film the impossible, whether its hauling a 340 ton steamship up a mountain or filming a period peace on 1/10th of the expected budget it all reinforces this persona that Herzog has fashioned for himself. In this, Herzog is constantly aware of his own persona and it dictates his dicision making process.