Written

by John Ostrander (story Jim Shooter). Art by Lee Weeks.

Written

by John Ostrander (story Jim Shooter). Art by Lee Weeks.

Colours: Maurice Fontenot, Rachel Menashe. Letters: John Constanza, Pat Brosseau. Editors: Mike Richardson, Bob Layton.

Predator vs. Magnus Robot Fighter 1994 (SC TPB) 64 pgs

Written

by John Ostrander (story Jim Shooter). Art by Lee Weeks.

Written

by John Ostrander (story Jim Shooter). Art by Lee Weeks.

Colours: Maurice Fontenot, Rachel Menashe. Letters: John

Constanza, Pat Brosseau. Editors: Mike Richardson, Bob Layton.

Reprinting: Predator vs. Magnus Robot Fighter #1-2 (1993 mini-series)

Rating: * * * (out of 5)

Number of readings: 2

Published by Dark Horse and Valiant

Mature Readers

For more Magnus see Magnus: Invasion, for more Predator see Batman vs. Predator II: Bloodmatch

One of a number of mini-series and one-shots featuring

the Dark Horse-owned Predators (licensed from the movie about a nasty alien

big game hunter battling spunky humans) paired off against other, well

known characters -- there have been a number of Batman vs. Predator mini-series,

Tarzan vs. Predator, even Aliens (another movie franchise) vs. Predator.

This time around it's Valiant's revival of the A.D. 4000 comic book hero,

Magnus.

The story has some decadent rich dudes in North Am, who

stage illegal hunts in the inner city, getting on the wrong side of a Predator

after stealing a trophy the alien had claimed from a previous victim --

an X-O cybernetic helmet (the X-O is something from another Valiant comic

book, and is kind of confusingly included here if you aren't already familiar

with it -- as I'm not). Magnus was already after the so-called sportsmen

himself, but quickly finds himself battling the Predator, as well.

Admittedly, there isn't too much to the story here. There

are so many ways it could go off into interesting ideas and twists (like

Magnus forced to protect the bad guys from the Predator), but never really

does, despite the promise in early scenes. Instead, it's more just a fast-paced

action-piece -- which, in itself, isn't a bad thing, per se. Shooter and

Ostrander haven't exactly strained themselves coming up with a plot, but

it's moderately entertaining and briskly paced.

My focus coming into this was Magnus, not the Predator.

After reading

Magnus Robot Fighter: Invasion

I had been looking for other Magnus stories and figured this would be a

good bet to get a complete story without any danger of finding it to-be-continued.

I have mixed feelings about it, as regards Magnus. The art by Lee Weeks

is exceptional, reminding me a little of David Mazzuccelli's work in Batman:

Year One but more robust and not as stylized. It's striking and moody...but...what

had appealed to me about Magnus: Invasion was the clean art style

evoking Magnus' creator Russ Manning. This is very well drawn...but it

doesn't feel like Magnus entirely. This is also a darker, more bitter

Magnus, at one point even suggesting he has more sympathy for the Predator

than the humans (though he seems to have divested himself of that odd bias

by the end -- there's little to choose between them, after all). Nor does

the story entirely exploit Magnus and his world as well as you might like

-- there are very few ways in which the story

had to be be about

Magnus. It could've been almost anyone fighting the Predator.

The Predator idea itself, I'll admit, seems a bit limited

for such a surprisingly successful comic book franchise. Interesting in

a movie, but against comic book heroes...well, how is the Predator different

from any other super villain? And here it seems a bit stale, as if the

creators are kind of going through the motions. There's little real mood

or any of the terror generated in the (first) motion picture.

It's also worth noting that this is kind of gory in spots

-- not surprising given the movies. Likeewise, there's some mildly mature

subject matter in language and scenes (Magnus and girl friend Leeja in

bed together), though nothing that wouldn't be aired in U.S. prime time.

It's the violence that a reader might want to be prepared for (though only

in a few panels).

Of course, this may have been signaling a "new" direction

for Magnus. Around this time, John Ostrander took over the scripting of

the regular Magnus Robot Fighter comic where he kicked things off

(#21) by beginning an epic storyline where earth is attacked by outer space,

homicidal robots (looking a lot like the critters from the movie "Aliens")

who kill off most of the series' supporting characters in various grisly

ways. It was a move that some pundits felt derailed an otherwise promising

revival of the robot fighting guy.

This is entertaining enough to help kill an hour...but

will read better if you can get it, or the original mini-series, on sale.

The story itself is also only 48 pages. I'm not sure what they did to bulk

this collection up to 64 pages.

This is a review of the version serialized in the Predator

vs. Magnus Robot Fighter mini-series.

Cover Price: $11.95 CDN./$ 7.95 USA.

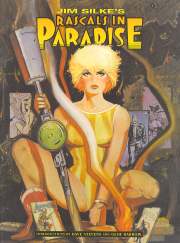

Written and illustrated and painted by Jim Silke. Rascals in Paradise 1995 (SC GN)

102 pages

Rascals in Paradise 1995 (SC GN)

102 pages

Letters: L. Lois Buhalis.

Reprinting the three issue mini-series in over-sized, tabloid dimensions;

Rating: * * * (out of 5)

Number of readings: 1

Recommended for Mature Readers

Additional notes: sketch gallery; intros by Dave Stevens and Geoff Darrow; retrospective of Silke's career.

Published by Dark Horse Comics

Rascals in Paradise is at once very modern and yet very old

fashioned at the same time. It's old fashioned in that it's a deliberate evocation (with

tongue-firmly-in-cheek) of pulp-era adventures. Set in the distant

future, the location is a planet that has been remodelled as a tourist

trap meant to evoke the nostalgic days of 1930s earth...but something went

wrong and, instead of evoking the real 1930s, it evokes the pulp fiction

world of dank jungles, lost tribes, and jodhpur-wearing adventurers. The

logic behind this is vague. (If the world was artificially created, who

are these people who inhabit it? Are they real or constructions?) The plot

involves kidnapped damsels, jungle cults, and secret maps. Like I said, old fashioned.

On the other hand, there is a modern aspect to Rascals in that it features a "mature readers" story

with plenty of nudity and racy material. This isn't so much a re-creation

of old time adventure stories, as it's a re-construction of the milieu with

modern explicitness.

The result is hit and miss.

Written and illustrated by Jim Silke, this was his first

foray into sequential art ("funny books" to you and me). Before that, Silke worked as a jack-of-all-trades

in Hollywood for many years, publishing fanzines, writing screenplays (including the 1985 version of King Solomon's Mines),

hanging out with Hollywood legends like Sam Peckinpah, and working as an

artist and photographer in the glamour field (ie: doing pictures of beautiful

women). It's that latter career that is clearly fueling Rascals in Paradise.

Silke's a good artist, but not quite a great one. And

his newness to the medium leads to some rather flatly presented scenes,

particularly action scenes, and even some confusing ones (where a caption

is sometimes used to bridge two panels that otherwise don't flow clearly

one from the other). His painted style can certainly capture a beautiful woman

or two, and his technique adds to the whole "nostalgia" flavour:

soft, blurry colours, and a sometimes unsure handling of figures

(with hands and feet sometimes indistinct) actually evoking old pulp magazine

cover painters, as if someone like Margaret Brundage (of Weird Tales fame) had taken to illustrating

comic books.

The story is a brisk romp, only vaguely coherent, and

never takes itself too seriously. This latter aspect presumably explains

how Silke could get away with all the blatant sexploitation without raising

hardly an eyebrow among critics -- including a ravishment scene (off camera

and semi-consensual) and a flagellation scene (somewhat demurely depicted,

focusing as much on the people around the scene as the damsel herself).

It's a joke homage.

On the plus side, one can certainly appreciate the wanton

uninhibitedness of the story (well, at least if you're a guy). Others have

tried similar efforts, but usually with a result watered down and self-consciously

apologetic. Silke clearly takes the attitude that if he's going to do this

story...he might as well do it, and political correctness be damned

(resulting not just in underclad women, but natives speaking in pidgin

English). And not just the nudity, but the story itself benefits from this

attitude, with Silke throwing in everything but the kitchen sink -- from

jungle temples and sacrifices, to jet packs and laser guns.

At the same time, if you remove the nudity, and the sexploitation,

I'm not sure the rest is strong enough to stand on its own. The characters

never really gel into people you care about (you can't even be sure who

the main character is, with the nominal heroine being "Spicy" Saunders

who arrives to join the local jungle patrol, but there's also her immediate

supervisor String, and a roguish mercenary, and a damsel in distress who

they're trying to rescue). At first, the story makes a loose kind of sense -- at least enough to get us from one scene to the next. But by the end, it

just seems to get muddier and muddier, with too few explanations. "Spicey"'s

suit has strange properties, like turning invisible and rendering

her nude at various moments, but it has other abilities which manifest themselves in

the climax with little justification. Even, as noted, the "reality" of the

story doesn't seem to permit even a cursory scrutiny.

The story even ends a bit inconclusively. Oh, sure, everyone's

rescued who's going to be, but new questions are raised. At the end of

the book is a sketch gallery showing preview images from the next storyline. But either sales for this first storyline weren't what they were

hoping for (though this TPB collection is still in print) or Silke just

lost interest, because to my knowledge, no further adventures of "Spicey"

and the gang were published. There's a problem with writing a story in

which some threads are meant to be part of something larger...if the creator

doesn't have the discipline to follow through. Silke's only other foray

into the comicbook field, I believe, was the later, similarly-themed Bettie

Page: Queen of the Nile (taking the real life 1950s pin-up queen and featuring

her in a racy, tongue-in-cheek sci-fi adventure).

The bottom line is, if you don't expect much, Rascals

in Paradise can be campy fun (more for guys than gals) simply for its unapologetic

luridness (lots of nudity, though no full frontal) and the old fashioned

idiom it evokes. But as a story it's uneven, becoming more unsatisfying

by the end.

Cover price: $23.75 CDN./ $16.95 USA.

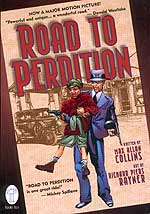

Road

to Perdition 1998 (SC GN)

304 pages

Road

to Perdition 1998 (SC GN)

304 pages

Written by Max Allan Collins. Illustrated by Richard Piers

Rayner.

Letters: Bob Lappan. Editor: Andy Helfer.

Rating: * * (out of 5)

Number of readings: 1

Additional notes: intro by Collins (at least, in the 2002 re-issue)

Published by DC Comics/Paradox Press (and Pocket Books)

In 1930 Illinois, Michael O'Sullivan is a hit man for mobster, John Looney. After O'Sullivan's son, Michael Jr., witnesses a mob killing, his family is targeted by the Looney clan -- his wife and youngest son are killed, forcing the two to hit the road, Michael Senior determined to get revenge.

Road to Perdition is a crime thriller set, sort of, amid real characters -- John and Connor Looney were real, as were Al Capone, Frank Nitti, Eliott Ness and one or two others who makes appearances. But the basic narrative is fiction (apparently there was a hitman who the Looney's turned on, but one infers he didn't hit the road with his son or bear much relation to this character). Collins is no stranger to historical fiction (having written some novels about Ness) so it's too bad he's willing to play so fast and loose with history.

Although first published in 1998, this gained a bigger profile after it was turned into a big budget, critically acclaimed -- and, frankly, somewhat better -- motion picture.

It's presented in a style evocative of Japanese manga comics -- slightly larger than a pocket book, in black and white, with only three or four panels per page. Collins makes no secret of his love of manga, nor of the influence of Lone Wolf and Cub, a Japanese comicbook series (and movies) about a rogue Samurai, betrayed by his boss, who travels the road with his son (in that case, a baby).

Clearly

the book wants to be literature. It ain't about men-in-tights with fancy

powers; it's rooted in a gritty historical milieu, and it plays around

with themes of honour and Catholicism. It starts out interesting, benefiting

from the period atmosphere, and the slightly atypical milieu for a comic

book. And benefits from our own expectations. But, ultimately, it's disappointing.

Clearly

the book wants to be literature. It ain't about men-in-tights with fancy

powers; it's rooted in a gritty historical milieu, and it plays around

with themes of honour and Catholicism. It starts out interesting, benefiting

from the period atmosphere, and the slightly atypical milieu for a comic

book. And benefits from our own expectations. But, ultimately, it's disappointing.

The basic story is, well, basic. Man's family is killed, man seeks bloody revenge. I'm sure Steven Segal has starred in a dozen films with that same plot. There aren't a lot of twists and turns, nor even any mysteries that need to be unravelled. The action scenes are protracted and repetitive -- O'Sullivan repeatedly walks into rooms, ostensibly to talk, and/or is unarmed, and thugs try to kill him. O'Sullivan, being a superduper assassin, wipes them out, sometimes employing objects at hand. The ease with which O'Sullivan can slaughter his way through odds of ten to one stretches credibility at times.

Plot-wise, there's a late story sequence where O'Sullivan tries to put pressure on Al Capone's mob to give him Connor Looney (who they are protecting) by robbing their business interests, hitting them in their pocket books. It's moderately interesting...but likewise proves repetitive and fails to build to anything.

At the story's core, and supposedly what makes it literature as opposed to just a comic book, is the father and son drama. Yet there's no real character growth or development. You might expect it to start out with Michael Jr. not liking his father, then coming to love him by the end, or loving his father at the beginning but, once he knows what his father does for a living, growing to despise him. Or some such variation. But their relationship doesn't really change one iota over the course of three hundred pages (though given the few panels, it's more like 100-150 pages).

There isn't a lot of characterization, period. O'Sullivan is one of those squinty-eyed, close-to-the-vest, man-with-no-name archetypes that are more defined by their dangerous cool than their multi-faceted personalities. While Michael Jr, despite being the narrator, is largely defined by his reflections on his father. The other characters are basically there to serve the plot, or provide a historical "guest" appearance, rather than to be explored as people.

The story's other big themes are honour and Catholic guilt. O'Sullivan is seemingly cast as a good man who happens to do bad things, frequently referred to as "honourable" -- a man who views his profession as no more morally ambiguous than that of a soldier fighting a war...despite the fact that he is supporting pimps, pushers, extortionists and murderers. Maybe if Collins had given us more background to the character, a sense that he got in too deep to get out. But this isn't about a man who lost his way. It's about a man who is doing what he was born to do -- but he does it with "honour". We can especially see the influence of Japanese Samurai fiction in this approach. At one point, O'Sullivan specifically states that he isn't responsible for what happened to his family -- and I don't think that's meant to be ironic. Sure, the Looney's are directly to blame, but indirectly, O'Sullivan is responsible for his family being involved in that world to begin with. And if you don't accept O'Sullivan's moral subjectivity, the story just becomes kind of creepy, as a sociopathic killer takes an impressionable child under his wing. Because O'Sullivan is a good Catholic, he lights candles for those he kills, and makes Confession regularly. I'm not that familiar with Catholicism, but aren't you supposed to confess to repent your sins? What's the point of confessing...if you have every intention of going out and committing the exact same sins again and again?

The art by Richard Piers Rayner got a lot of attention, and it is impressive to a degree. Heavily photo-referenced, there is a realism to figures and backgrounds that's quite impressive. But like a lot of photo-referenced art, it can be a bit stiff, with characters looking too much like they're posing, and where facial expressions seem copied from a finite number of reference images. Lengthy talking head scenes -- stretched out because, like a lot of modern comics, Collins often only allows one character to speak per panel -- can amount to a collection of rather non-specific head shots. In one later scene, a character is shot in the knee, yet when he speaks, instead of grimacing in agony, his expression wouldn't tell you he was even injured! Rayner might also have thought to give O'Sullivan a distinguishing characteristic -- a scar, a moustache -- because it was often hard to recognizze him.

Nor is Rayner's choice of composition anything spectacular -- there aren't any really stylishly dessigned scenes, or moodily composed images that necessarily augment the text.

Obviously, I read this with some mixed feelings, morally speaking, but the main problems are more narratively based. The ambience can only carry you so far before you notice it's a really thinly story, and not very fresh. There are too many stretched out gun battles and too little character development.

Interestingly, the motion picture stuck close to the comic in some ways, well diverging significantly in others (including slightly changing some names). The whole intent of the film is different, notably by underplaying the action-violence. Where in the comic O'Sullivan might get into a shoot out with ten guys...in the movie, it might only be two; in some scenes, the shoot out has been removed entirely! There's also considerably more attention paid to characterization, including adding a whole surrogate son-surrogate father dynamic to the relationship between the (anti-)hero and the mob boss that isn't really in the comic. The movie, like the comic, suffers from a certain thinness to the plotting, and neither really capture any sense of grief either O'Sullivan would surely be feeling over the death of their loved ones, but it's a more satisfying take on the story.

Both versions also have some (minor) historical lapses. In the comic, a character quotes the May West line about "are you glad to see me?"...in a story set before West had made any movies. While in the movie, the kid reads a Lone Ranger book, a few years before the Ranger had been created.

Collins has subsequently written a series of shorter graphic novels, under the title On the Road to Perdition, set within the framework of this book (since the graphic novel takes place over many months, that left a few windows in which to insert stories of the two O'Sullivan's on the road). He also wrote the text novel adapting the movie.

Cover price: $21.50 CDN./ $14.00 USA.

Written, illustrated and edited by Frank Miller.

Colours: Lynn Varley. Letters: John Constanza.

Reprinting: Ronin #1-6 (1983 deluxe mini-series)

Rating: * * * * (out of 5)

Number of readings: 3

Published by DC Comics

Mature Readers

A 13th Century Japanese ronin, killed in a bitter struggle with a demon, reappears mysteriously in a gone-to-hell 21st Century New York, his renewed struggle with the demon focusing on a bio-technology corporation that's developing a whole new form of living machine. The corporation's beautiful head of security, Casey, hunts the ronin, unaware that the real menace is the demon.

Frank Miller's unusual, stand-alone blend of SF, fantasy, martial arts, human drama, social satire, time slips, violent action and mystery -- yes, mystery -- is kind of like Philp K. Dick meets Edgar Rice Burroughs, filtered through Japanese Samurai films. Ronin was one of DC comics first forays into the field of "mature reader" comics. Frank Miller also experimented with a "cinematic"-style -- telling the story solely with dialogue; there's no voice-overs, thought balloons, or narration in Ronin. Ironically, although other writers instantly started emulating him, Frank Miller himself re-introduced narration in his own subsequent work, obviously recognizing the limitations of that technique (after all, the beauty of a comic book is it's a blend of cinema and literature and shouldn't slavishly imitate one or the other). Still, Ronin works well. Not only is Frank Miller a master of dialogue and panel composition, he also has the ability to invest his sometimes crude, though always dynamic, drawings with genuine expression and subtle nuances in a way that, even a lot of the great artists, can't.

Ronin is a gritty, exciting, atmospheric, completely off kilter work. Personally I can't think of anything else quite like it in novels, movies, or comics. I first read it all out of order, though, picking up back issues when I could, so my impression of it is a little distorted (I knew some of the surprise answers before I even knew there were questions).

When first released, it wasn't regarded as an unqualified success, and it's uneven in spots. Sometimes the action scenes can be a bit long, and the series is a bit too episodic in spots. Miller was obviously making some things up as he went along. In the first issue, reference is made to police, but subsequently we are told there is no police force in New York; important characters are introduced as late as the penultimate issue, and vital "clues", likewise, come in kind of late. But, viscerally, it's an exciting, memorable read.

Like a lot of Frank Miller's work, Ronin can be pretty violent, though for whatever reason (perhaps Miller draws gore so stylized) I don't find him as "icky" as some (the 2nd issue struck me as the most unpleasant). There's also some nudity. Most "serious" comic folk when doing "mature reader" stuff throw in violence and profanity, but their nudity is usual restricted to off-putting, disturbing scenes as in the Batman: The Killing Joke or The Sandman Mystery Theatre: The Tarantula (I'd hate to be the psychoanalyst listening to Alan Moore or Matt Wagner pontificate on sex and women); here, Casey spends an entire issue gratuitously in the buff (well, actually she spends most of an issue in shadow, and only a half-dozen panels in the buff), though it's, more or less, justified by the story.

This is a review of the version originally serialized in the Ronin mini-series.

Cover price: $19.95 CDN./$19.95 USA (O.K., it doesn't seem too likely the prices would be the same, so I'm assuming my information is wrong about one of them)