Wainwright's Introduction

Every walker who plans a cross-country expedition refers to his maps, looks for the footpaths and the bridleways and the areas of open access, links them together by quiet roads and lanes that avoid towns and busy traffic arteries, and so devises a pleasant route to his objective that he is free to walk, as is any man, without fear of trespass or restriction. This is precisely what I have done in the book. To the best of my knowledge the route described will commit no offence against privacy nor trample on the sensitive corns of landowners and tenants. It is a country walk of the sort that enthusiasts for the hills and open spaces indulge in every weekend. It's a bit longer than most, that's all. The point I want to emphasise is that the route herein described is in no sense an 'official route' such as the Pennine Way; it is a harmless and enjoyable walk across England, entirely (so far as I am aware) on existing rights of way or over ground where access is traditionally free to all. The walk is one I have long had in mind, and in 1972 finally accomplished; and I have committed it to print partly because the growing popularity of the Pennine Way indicates that many people of all ages welcome the challenge of a long-distance walk, and partly because I want to encourage in others the ambition to devise with the aid of maps their own cross-country marathons and not be merely followers of other people's routes: there is no end to the possibilities for originality and initiative. And partly, I suppose, because I like to write about my walks and by doing so live them over again. The route follows an approximate beeline (if a beeline can ever be approximate!) from one side of England to the other: from St Bees Head on the Irish Sea to Robin Hood's Bay on the North Sea, and if a ruler is placed across a map between these two points it will be seen at a glance that the grandest territory in the north of England is traversed by it; two-thirds of the route lies through the areas of three National Parks. It is never possible to follow a dead-straight beeline over a long distance without trespassing, climbing fences, wading rivers, perhaps swimming sheets of water, and walking through houses and gardens. The route given makes no attempt to follow a straight line: deviations are necessary throughout, primarily to avoid private ground but additionally to take the opportunity of visiting places of special interest nearby. Thus, although the straight line gives a mileage of 125, the route mileage is 190, half as far again. The countryside traversed is beautiful almost everywhere, yet extremely varied in character with mountains and hills, valleys and rivers, heather moors and sea cliff combining in a pageant of colourful scenery. It is of great interest both topographically and geologically, the structure of the terrain and the formations of the rocks showing marked changes from one district to the next. The route which has a bias in favour of high ground rather than low, is divided into convenient sections, each of sufficient distance to provide a good day's march for the average walker and ending at a place where overnight lodgings are normally available. Given reasonable weather, the walk can be done in two weeks, not rushing it nor trailing behind schedule. Some people who would like to do the walk may prefer to tackle the sections at intervals of time and possibly not in sequence, travelling from home on each occasion: this practice has other advantages, notably avoidance of the need to reserve a bed and the selection of fine clear days only. Everybody has a car these days, even me (and in my case, a good-looking competent chauffeur to go with it) and most sections of the route are within reach of the urban areas of the northern counties. The walk is described from west to east. It is generally better in this country to walk from the west or south so as to have the weather on your back and not in your face. In the case of this particular walk it is perhaps unfortunate that the grandest part of it, through Lakeland, comes so early, but those who do not already know the heather moors of north-east Yorkshire can be assured that they form a fitting climax. A. Wainwright, 1973 |

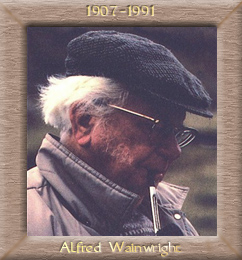

Wainwright's Coast to Coast walk